c/o Hong Kong or Shanghai Bank Yokohama, February 13, 1914 Dear Professsor Sargent, I am leaving by the 8:30 a.m. train tomorrow for Kagoshima in the extreme south of Japan. From there I go to Yakoshima where, I am told, fine forests of wild Cryptomeria occur.

Ernest Henry Wilson

Some months ago, I received a lovely letter from a colleague working at the Royal Tasmanian Botanic Gardens in Hobart, Tasmania. The writer described a recent hiking trip she’d taken to Yakushima, the southernmost island of Japan. Her group came across many adult, endemic Cryptomeria japonica (many of them aged thousands of years), commonly known as Yakusugi or shortened to Sugi—the national tree of Japan. During the course of her journey, the “Wilson stump” intrigued her the most. This huge, moss-covered Yakusugi cedar remnant, named after renowned plant explorer Ernest Henry Wilson (1876-1930), was first encountered and documented by Wilson in February 1914 during his fifth expedition to Asia (his third for the Arnold Arboretum). He had specifically set out to study cherries, azaleas, and conifers, along with Japanese horticultural practices.

Tomoko Furui explains circumstances of Wilson’s expedition in her recent book, Wilson’s Yakushima: Memories of the Past. Jirosuke Maki, one of Wilson’s aides at the time, recalls how on February 21, 1914, Wilson returned to his base camp, and seemed in excellent spirits in spite of the damp, cold weather. Wilson explained he had spotted what he thought was an enormous cave and that they should all investigate further. The weather cleared the next morning, and in the course of their journey the party encountered what turned out to be a massive, hollowed-out Yakusugi stump. Sensing the uniqueness of the discovery, Wilson began to carefully set up his camera.

Furui goes on to explain, “The atmosphere of this photograph is obviously different from that of other photographs taken by Wilson on Yakushima. This one looks like a commemorative picture; it does not seem that human subjects were arranged just as tools for showing the size of the tree. No other photographs have as many individuals in such size and in such a conspicuous manner.”

Wilson’s stump is one of the trees felled in 1586 on the order of Hideyoshi Toyotomi (1536-1598), a great “daimyo” lord known historically as the unifier of Japan. The purpose of the tree was to build a temple for the great Buddha statue at Hoko-ji temple in Kyoto. The stump sits at an altitude of 1,100 meters on the Ohkabu Mountain Trail near the center of the island. These Cryptomeria remnants are also known locally as domaiboku, “buried trees in the ground.”

Measuring a circumference of 50 feet, rife with surface vegetation, and believed to be 3,000 years old, the Wilson stump is enormous even by Yakushima standards. Twenty-five to thirty adults can stand comfortably inside the 338 square-foot hollow, and the skyward view is heart-shaped—retired Senior Research Scientist Peter Del Tredici informed me that the stump is locally celebrated as a sensible location to bring a first date. A mountain spring Shimizu flows from the interior, and in a tiny corner rests the small Mokkon Shrine, dedicated to the patron god of Yakushima.

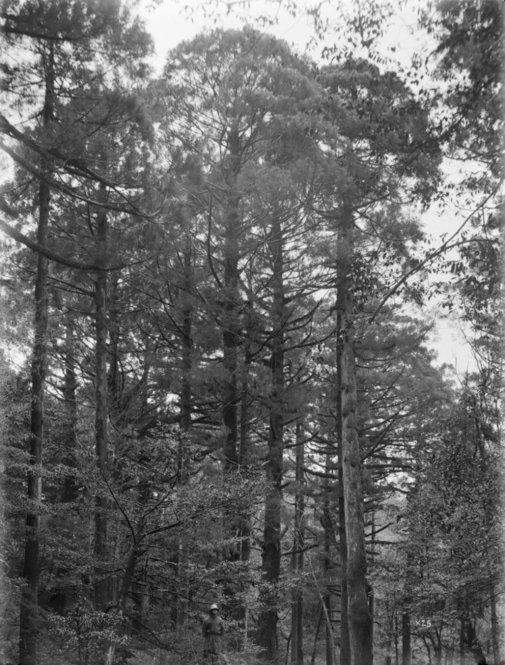

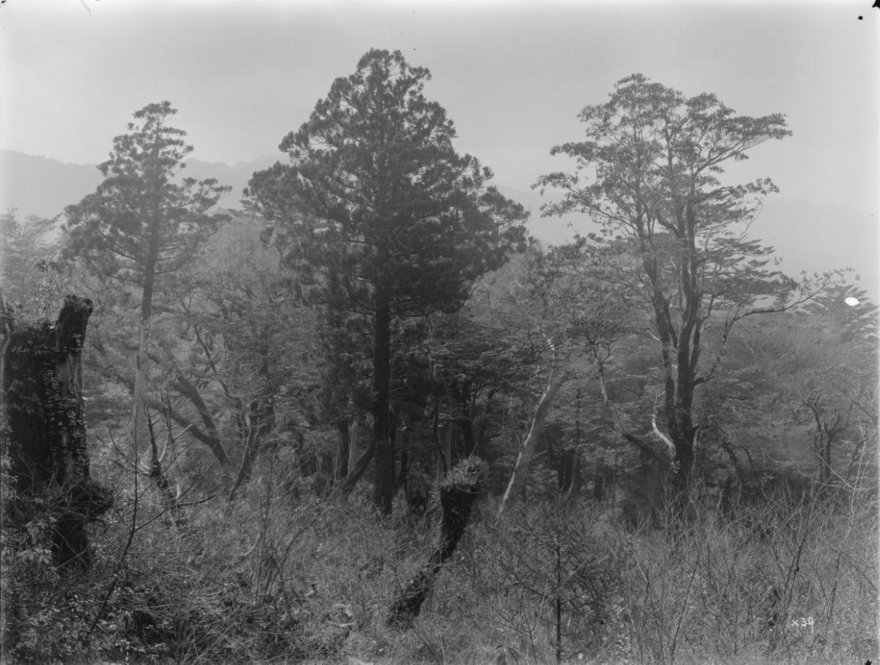

Publishing his findings in The Conifers and Taxads of Japan (1916), Wilson noted the dominance of Cryptomeria on Yakushima, and how the combination of abundant rains and rotting forest floor vegetation characterized that island’s ecosystem. As was his custom, Wilson also photographed the deepest reaches of the forest and captured breathtaking landscape imagery.

Wilson wrote to Arboretum director Charles Sargent on March 3, 1914:

“I have much pleasure in reporting my safe return to Kagoshima from a successful trip to the island of Yakushima where I found most wonderful forests. I collected about 150 species in recognizable condition and took five dozen photographs.

The island lies 92 geographical miles south of Kagoshima . . . it is about 50 miles in circumference and composed mainly of granite; the highest point is about 6,200 ft. above sea level. Around the coast are a few small villages, a little cultivation, and a narrow savannah belt; the extreme summit is said to be covered with bamboo scrub. The rest of the island is covered with dense virgin forest of which 99% of the constituent parts are evergreen . . . 60% conifers, 45% of which is Cryptomeria; the remaining 15% is of Abies firma and Tsuga Sieboldii with odd trees of Chamaecyparis obtusa and Torreya nucifera. The forest floor mainly consists of rotten or rotting tree limbs — chiefly Cryptomeria on which huge trees and a wonderful Cryptogamia flora luxuriates.

There can be no question about the Cryptomeria being truly wild. The adult trees average 80-90 ft. x 15-20 ft. I saw none over 100 ft. high. The oldest trees mostly have the tops broken off and the biggest of these measured 30 ft. in girth. Of dead stumps the largest I saw measured 50 ft. in girth seven feet from the ground . . . This wood is noted for its close texture and exciting qualities.”

It is likely that Wilson is writing here of the remarkable domaiboku that would later honor his name. Almost a century to the day when Wilson discovered the tree, the Wilson stump remains one of Yakushima’s most famous attractions.

Yakushima was added to the UNESCO World Heritage list in 1993, and conservation safeguards are in place to preserve the ancient forests’ beauty for future generations. It is forbidden to cut down Yakusugi cedars, but the domaiboku stumps are allowed to be extracted and used in fine woodworking.

SOURCES

Arnold Arboretum Library of Harvard University, Boston, Mass. Papers of Ernest Henry Wilson, 1896-1952; Series W.XIV: Correspondence, 1899-1930; Subseries W.XIV:A: Letters written by EHW in the field to the Arnold Arboretum, 1906-1922; From Japan, February 1914-January 1915. III EHW, box 21, folder 7. Handwritten letter / Transcribed letter.

Furui, Tomoko. Wilson’s Yakushima: Memories of the Past. Kētīshīchūōshuppan, 2013.

Harvard University Library Open Collections Program. “Expeditions and Discoveries: Sponsored Exploration and Scientific Discovery in the Modern Age. Ernest H. Wilson Expeditions to China, Japan, Korea, Formosa, and Islands in the Japanese Sea 1899–1919.”

Wilson, Ernest Henry, 1876-1930. The Conifers and Taxads of Japan. [Harvard] University Press, 1916.

( Publications of the Arnold Arboretum ; no. 8 )

Yakushima Environmental Culture Foundation. Diagram Yakushima. Kagoshima Yurakukan, 2000.

Wikipedia. “Yakusugi” and “Wilson Ltd. [stump]”

—Larissa Glasser, Library Assistant