In spring of 2022, Harvard University President Larry Bacow shared the findings of the Presidential Committee on Harvard and the Legacy of Slavery, a major initiative focused on researching and day-lighting connections between Harvard and its community to both the institution and economy of slavery. Among the Committee’s findings associated with the Arnold Arboretum is a major benefactor who made his fortune trading goods produced by enslaved people, the institution’s historical connections to the Atkins Institution in Cuba, and the close ties of some instructors at the Bussey Institution to the eugenics movement. At the Arnold Arboretum, we welcome this opportunity to better understand our past as important historical context in our efforts to make our landscape more welcoming and enriching to everyone.

As President Bacow notes in his message about the report, Harvard and its affiliates must be dedicated not only to the pursuit and dissemination of knowledge, but also to championing the truth. Harvard’s immense research and discovery effort was conducted with the understanding that a more equitable Harvard begins with acknowledging and mitigating a history marked by profound injustice and human suffering. Revealing, interrogating, and reflecting upon this history are essential steps to making all parts of Harvard accountable to its past and resolute in shaping the character of its future.

Benjamin Bussey, Land Donor

A large portion of the Arnold Arboretum—land now owned by the City of Boston and leased back to Harvard to operate the Arnold Arboretum—was donated to the University in the nineteenth century by Benjamin Bussey, a Boston merchant and one of the richest men in New England at the time. He did business with a number of other local merchants who also had ties to the University and are profiled in the Legacy of Slavery report such as Thomas Handasyd and James Perkins, Israel Thorndike, and John McLean.

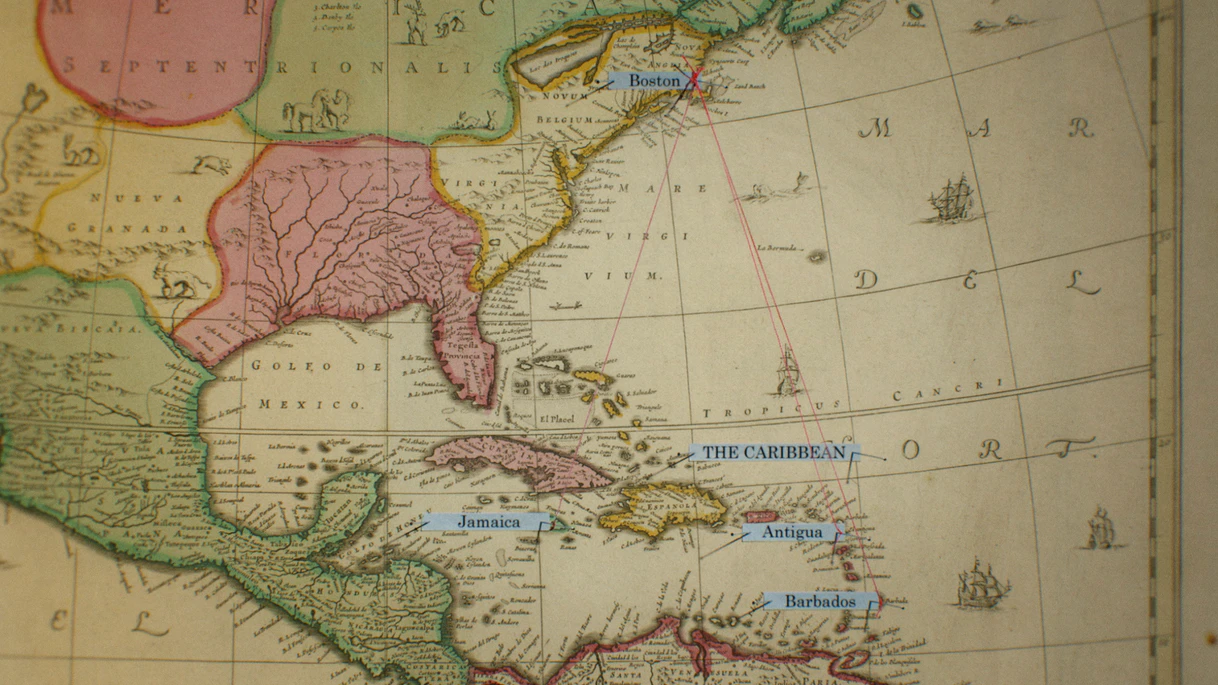

After service in the Revolutionary War, Bussey went into business as a silversmith. He expanded into the trade in luxury goods about 1790, engaging in the “triangle trade,” buying provisions in New England such as timber and coarse cloth that were shipped to the American South or the Caribbean for use in the plantation economy. The provisions were sold to buy products produced by enslaved people, including sugar, cotton, tobacco, and coffee. His ships took those products to Europe, where they were sold, and the profits used to purchase luxury items such as cotton shawls, dinnerware, and barrels of decorative feathers that were sold in markets in the American Northeast.

Bussey engaged in this business model until about 1809 when Jeffersonian embargoes and rising impressment of the crews of his ships by the British Navy made his ventures increasingly unprofitable. He then turned his attention to real estate speculation in mid-coast Maine. Later in 1819, he opened woolen mills in Dedham, Massachusetts.

In 1806, with the fortune he made in the triangle trade, Bussey purchased the property in Jamaica Plain that he would bequeath to Harvard, and that would become the original footprint of the Arnold Arboretum in 1872. Thus, while Bussey has traditionally been acknowledged as a founding benefactor of the Arboretum, an unknown number of enslaved people—whose consent was never asked for—must be acknowledged for the immense labor and suffering they endured for him to amass his wealth and to acquire the lands where the Arboretum sits today.

Information concerning Benjamin Bussey is included in the report’s summary of key findings (pp. 11-12), and his bequest to Harvard is considered in a section dedicated to donors (p. 22; pp. 25-26) with financial ties to slavery.

James Arnold, Benefactor

In contrast to Benjamin Bussey’s trade in goods produced by the enslaved, the Arboretum’s namesake donor—James Arnold of New Bedford—was, like members of his extended family, a staunch abolitionist. His wife’s family, the Rotches, were Quaker whaling merchants and shipowners, initially located on Nantucket in the early 1700s. In the second half of the 18th century, they built the whaling business in New Bedford.

Young James Arnold became part of the family when he married Sarah Rotch in 1807. Their household was renowned in the area for its generosity and it is rumored that they were a stop on the Underground Railroad. In 1868, Arnold bequeathed a portion of his vast fortune in trust to create a public arboretum. Through the efforts of his brother in law George Barrell Emerson, Arnold’s generous bequest was joined with Bussey’s gift of land and the Arnold Arboretum was created in March 1872.

As a beneficiary of his philanthropic legacy, we must acknowledge that the fortune James Arnold bestowed on the Arnold Arboretum derived from the whaling industry, a primary driver in the decline and near extinction of many cetacean species.

Edwin F. Atkins and the Atkins Institution

Boston sugar magnate Edwin F. Atkins acquired the Soledad Plantation in Cienfuegos, Cuba in 1884. When Atkins took over ownership of the property, nearly 100 patrocinados—a word that translates as “apprentices,” but actually refers to people bound to the property on which they worked—were held in bondage there, four years after Cuban emancipation. Atkins was very concerned about retaining the patrocinado labor force to reduce his business costs, even after some of those laborers were legally free.

In 1899, Atkins engaged Oakes Ames (Supervisor of the Arnold Arboretum from 1927-1935) to conduct research into improving sugarcane varieties. The plantation became Harvard’s tropical botanical research station at that time and later operated as the Atkins Institution of the Arnold Arboretum between 1932 and 1961. Arboretum staff including Ames, taxonomist Alfred Rehder, and dendrologist John George Jack conducted research there. After the Cuban revolution, management was taken over by the Cuban government and Harvard had no further involvement. Today it is the Cienfuegos Botanical Garden.

The Atkins story is detailed on pages pp. 26-27.

The Bussey Institution and Its Ties to Eugenics

The Bussey Institution was founded by Harvard College in 1871 as an undergraduate program in agriculture, endowed as part of Benjamin Bussey’s 1842 bequest that also included his Jamaica Plain property. It was converted to a graduate program in applied biology, and in particular genetics, in the early 20th century. Students could matriculate at the Bussey, a degree granting school in the University, and study botany and dendrology on the Arboretum grounds under Arboretum staff members such as John George Jack. A number of Chinese students were educated there, including H.H. Hu (Hu Hsen-Hsu, Hu Xiansu, 胡先骕) who along with W.C. Cheng (Cheng Wan-Chun, Zheng Wanjun, 郑万钧) identified the living Metasequoia glypostroboides in the 1940s.

The history of the Bussey Institution becomes problematic when we learn about a prominent staff member’s ties to the eugenics movement in the United States. Professor William E. Castle, who taught at the Bussey for many years was a leading American eugenicist who advocated the grotesque belief of enforced sterilization of the “feeble minded.”

William E. Castle, the Bussey Institution, and the eugenics movement is detailed on pages pp. 40 and 42-43.

Say Their Names

An important part of the Committee’s work was to compile a list of enslaved persons (pp. 61-72) connected to Harvard and its community. The Arnold Arboretum joins Harvard in commemorating their lives and memory. Reading these names gives us all an opportunity to reflect on this history, ponder the meaning and value of individual freedom, and contemplate the suffering of individuals who lived and worked in bondage.

Recommendations and Future Steps

The report also details recommendations for how Harvard as a community can redress its legacy with slavery, including committing $100 million to activities both immediate and in the longer term through an endowment. At the Arnold Arboretum we are committed to sharing this history and its lessons, including providing additional context to visitors on tours, public programs, and stops included in our Expeditions application. Additionally, information on our website pertaining to Benjamin Bussey and the Atkins and Bussey Institutions will be amended to reflect on this history as well. At the Arnold Arboretum and across the Harvard University community, the work to recognize and redress the persistent effects of slavery will require our sustained and ambitious efforts for years to come.

This page was written with contributions by Jon Hetman, Lisa Pearson, and William (Ned) Friedman on behalf of the Arnold Arboretum community.