Most of the temperate trees and shrubs that grow in the Arnold Arboretum’s living collections ripen their fruits in late summer or autumn. As a result, expeditions to wild places to collect seed take place around the same time. Unfortunately, this means our collections may lack species whose fruits are ripe for the picking much earlier in the growing season. Some of these species are targeted as part of the Campaign for the Living Collections, so this past May I visited several vernal bearers in Japan. I was joined by Professor Mineaki Aizawa and his graduate student Tatsuhiko Shibano from Utsunomiya University, who also hosted the Arnold Arboretum and colleagues last autumn.

Although we collected other species as well, the expedition’s focus was Acer pycnanthum, a maple closely related to North America’s Acer rubrum and Acer saccharinum (red and silver maples, respectively). Like these two, A. pycnanthum produces a profusion of reddish flowers in late winter to early spring, and after a brief time, sheds its ripened seeds – typically in May. There are but some 1500 trees of this rare species left in the wild, occurring in central Honshu, and limited to acidic seeps. We visited several populations of this conservation-status species, documented the trees’ habitat and condition, and collected seed and herbarium vouchers.

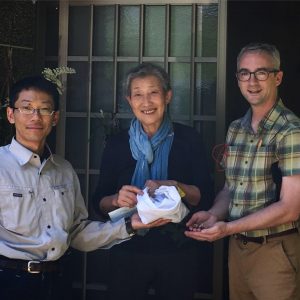

The first spot, in Sendanbayashi, Gifu Prefecture, was a mesic woodland at the edge of rice paddies and old drainage canals. As soon as I got out of the car, I could distinguish the trees in the distance from other broadleaved trees due to their grayish-green color, particularly as the wind ruffled the leaves – the leaf undersides are covered in a waxy, white bloom. The species’ similarity to our two native maples was uncanny, it was like sauntering up to a Massachusetts swamp and visiting familiar friends. As we approached the trees and looked up, we found them devoid of fruit, for they had shed their winged samaras about a week earlier. But, there was nothing to worry about because Mineaki had deployed a half-dozen seed collection traps (imagine mesh laundry hampers) below the trees a few weeks beforehand. As the fruits were dispersed by the wind, they spun into the traps to await our arrival. Collecting couldn’t have been easier!

In another population near Bicchuubara in Nagano Prefecture, we found trees in a rich forest, perched on a gentle slope fed by natural springs. Most of these trees had also shed their seeds, which were gracefully captured in the fern fronds below (nature’s own seed traps!). However, a few trees still bore their pinkish fruits on long stalks, or peduncles, allowing us to collect complete herbarium specimens.

Our collections of Acer pycnanthum will play a number of pivotal ex situ conservation roles at the Arnold Arboretum and beyond. After our seeds germinate and the trees grow to transplantable size, we will add them to the permanent living collections where they can be shared with scholars and visitors alike who may never get the chance to see them in the wild. We will also share seed with other gardens and arboreta so that they may similarly enrich their collections. This step also provides additional insurance: It is unwise to put all your eggs in one basket, particularly for valuable and rare species. Experience has taught us the value of diversifying the number of gardens and environments attempting the species’ propagation and cultivation.

I cannot wait to see these seedlings germinate, and in the coming decade or so, see them flower and fruit for the first time. And, each time I do, I’ll fondly recall the memories of seeing these rare beauties in nature.

From “free” to “friend”…

Established in 1911 as the Bulletin of Popular Information, Arnoldia has long been a definitive forum for conversations about temperate woody plants and their landscapes. In 2022, we rolled out a new vision for the magazine as a vigorous forum for tales of plant exploration, behind-the-scenes glimpses of botanical research, and deep dives into the history of gardens, landscapes, and science. The new Arnoldia includes poetry, visual art, and literary essays, following the human imagination wherever it entangles with trees.

It takes resources to gather and nurture these new voices, and we depend on the support of our member-subscribers to make it possible. But membership means more: by becoming a member of the Arnold Arboretum, you help to keep our collection vibrant and our research and educational mission active. Through the pages of Arnoldia, you can take part in the life of this free-to-all landscape whether you live next door or an ocean away.