A look at the people and events that brought the Arnold Arboretum to life 150 years ago

On March 29, 2022, the Arnold Arboretum observed the 150th anniversary of its founding. Our celebratory sesquicentennial year provides a fitting opportunity to remember some of the people who helped create and form this institution through their foresight, beneficence, and hard work. Together, they forged America’s first public arboretum on the idea that a museum of living trees and woody plants from around the globe would benefit both science and society.

For over 7,000 years, the land on which the Arnold Arboretum now sits has been inhabited and used by diverse societies and cultures of Indigenous Peoples, including most recently, the Massachusett Tribe. Europeans settled here in the 1630s and cleared the land for farms. In 1806, Boston merchant Benjamin Bussey purchased an estate on this land, which he bequeathed to Harvard College in 1842 along with funds to create a school of agriculture and horticulture.

Bussey came from modest origins in Stoughton, Massachusetts and honed his mercantile skills during the American Revolution as a quartermaster. After the war, he went into the silversmithing business and from there to trading in luxury goods in New England and in Europe. Later he speculated in real estate and ran woolen mills in Dedham, Massachusetts. His Jamaica Plain estate—Woodland Hill—allowed Bussey to develop his horticultural interests as a gentleman farmer, and traces of lilac plantings he established still grow today on Bussey Hill.

Born almost a quarter-century after Bussey, James Arnold was a New Bedford whaling merchant. Like Bussey, he was also a gentleman farmer, and developed his 10-acre estate in the heart of the city into a pleasure garden. Also like Bussey, Arnold arranged for a generous bequest that would ultimately support the creation of a public arboretum after his death in 1868.

Arnold’s brother-in-law, George Barrell Emerson, was among the executors of his estate, and―along with fellow trustees John James Dixwell and Francis Parker―he masterminded the transfer of Arnold’s bequest to Harvard College and its subsequent pairing with Bussey’s bequest of land. It is interesting to note that Emerson, a pioneer in the education of girls, was also a noted dendrologist who authored a book on the trees of Massachusetts.

The great American botanist Asa Gray also had a hand in the founding of the Arboretum—in fact, it may have been Gray who planted the idea of a public arboretum in Emerson’s mind. Gray, who served as head of the Harvard Botanical Garden that existed in the environs of today’s Garden Street in Cambridge, was familiar with the Bussey parcel. Although it was about four miles from campus, Gray believed the site would be large enough to curate a complete collection of the world’s temperate woody plants.

On March 29, 1872 an indenture was signed between the Arnold trustees and the President and Fellows of Harvard College to convey the Arnold bequest to the University for the creation of a public arboretum on Bussey’s former estate in Jamaica Plain.

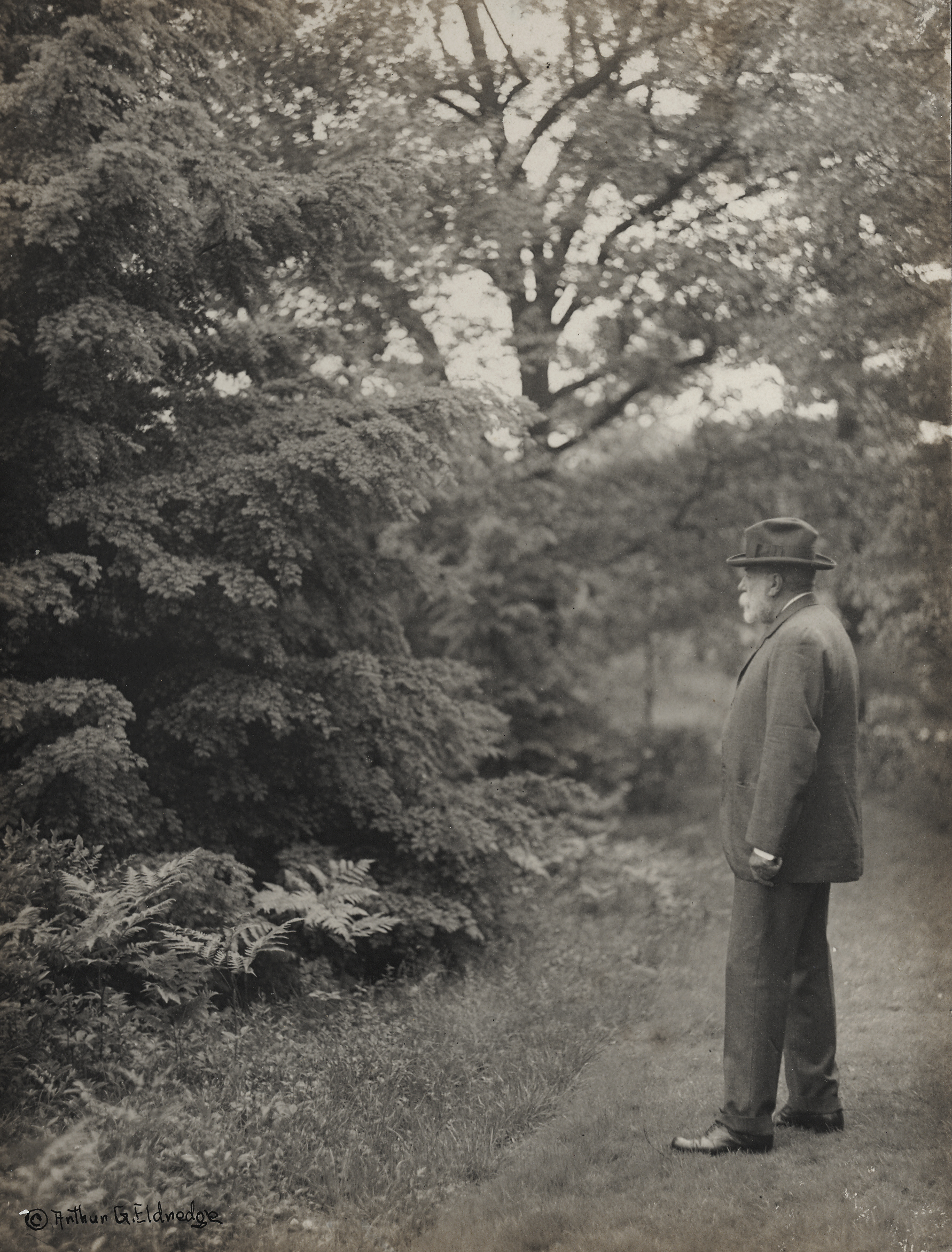

In 1873, Charles Sprague Sargent was appointed director of the new arboretum. He was born in 1841 to an old Boston Brahmin family and graduated from Harvard College in 1862. After serving in the Union Army during the Civil War, he toured the gardens of Europe, and then returned to manage his father’s estate, Holm Lea, in Brookline. Sargent found his calling as a botanist and administrator, guiding and shaping the Arboretum with a firm hand in the institution’s first half-century until his death in 1927. During his long and storied tenure, he oversaw the design and construction of the arboretum landscape and creation of the living collections, directed a census of the trees of North America, traveled the world and launched the Arboretum’s work in plant exploration, created a Silva of North America in fourteen volumes, and engaged collectors worldwide to bring thousands of plants into the collections of the Arnold Arboretum.

Soon after becoming director, Sargent partnered with pioneering landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted to draw up a proposal for the design of the grounds and the layout of plant collections. At this time, Olmsted was well known and highly regarded for his work with Calvert Vaux on Central Park in New York City.

As plans began to take shape, Sargent realized that Arnold’s bequest, while generous by the standards of the day, would not cover all the expenses required to achieve his expansive vison for the Arnold Arboretum. Plants and their acquisition stood foremost as a budget priority, but significant infrastructure costs had to be handled as well and proved beyond the means of Arnold’s nest egg.

To overcome this challenge, a partnership between Harvard and Boston was conceived in which the University would give title of the Bussey land to the City as part of parklands held in the public trust. In other words, Harvard would grow the plants and run the Arboretum while the City would cover infrastructure needs and security. Olmsted agreed with the plan immediately, and in fact Sargent later credited Olmsted with devising the idea. First floated in 1878, the proposal was not a sure bet, with Sargent himself mounting a campaign to convince Park Commission officials, city counselors, and University administrators to agree.

The wheels of civic progress often turn slowly, and the Boston City Council did not vote on the proposal until October 1882—in fact, they turned it down at first. Sargent and Olmsted sprang immediately into action, mounting a media campaign to sway public opinion—and, ultimately, the votes of City Council―in favor of the plan. A petition they circulated among Boston’s most prominent citizens garnered more than 1300 signatures in support. The campaign seemed to move the needle, for when the measure came up for vote again on December 27, it passed. It would take another year to iron out the terms, but the indenture was signed on December 20, 1883. In it, Harvard agreed to give the land of the Arboretum to the City but would lease it back in a 1000-year agreement (with an option for one renewal) for $1 per year. The City agreed to construct and maintain the institution’s infrastructure, and the University agreed to open the Arboretum to the public at all reasonable times (“dawn to dusk”) and abide by guidelines governing public park spaces.

By 1892, large numbers of trees and shrubs were in place across the landscape, the infrastructure was finished, and the public could enjoy the landscape and “the arborescent vegetation of the north temperate zone” by carriage, on horseback, or on foot. Additional property would be added to the Bussey lands when the Peters Hill in Roslindale was added in 1895. Nearly a century later, the Bussey Brook Meadow would be transferred to the Arboretum and swell its acreage further, as well as connect the Arboretum landscape to Washington Street and the Forest Hills MBTA station.

During its first two decades, the Arnold Arboretum took shape as an institution and the landscape so treasured today transitioned from a rural estate and working farm to a world-renowned botanical institution and research collection. Through the efforts of many individuals and the generosity of many more, the Arnold became a beloved spot to enjoy the beauty of nature and Olmsted’s magnificent vision, as well as a truly unique and valuable center for the study and appreciation of woody plants. These strong traditions, nurtured and stewarded since our founding, continue to guide and inspire us as we embark on the Arboretum’s next century.