It was early March 1912, on the banks of the Yellow River, 450 miles south of Beijing. An Arnold Arboretum plant collector and his three-man escort had ridden more than five hundred miles east from Minxian, in Gansu Province, through a region devastated by the Xinhai Revolution. The revolution had toppled the last Qing emperor and replaced the centuries-old imperial system of government with a republic, which was struggling to establish its authority against a plethora of regional warlords. The roads were alive with bandits, and food and shelter hard to find, but the collector’s journey to date had been uneventful. He and his escort were drawing near their destination, the railhead to Beijing in Honan (now Luoyang), the provincial capital of Henan Province. Suddenly, they were ambushed by a group of mounted men, who fired as they charged, killing two horses in the first moments of the attack.

It’s unlikely that the bandits knew what the travelers’ saddlebags and packhorses’ loads comprised, still less that they coveted the herbarium specimens and the seeds and tubers laboriously collected in Gansu and Tibet over the previous year. But a foreigner was sure to be carrying silver specie to pay his way on the road, and the surviving horses would fetch a good price.

The botanist, however, had other ideas. He drew a lever-action rifle from the scabbard beside his saddle and, as he would later write, “made a stand,” shooting three of the attackers and several of their horses. His escort joined in, driving off the bandits, and the party galloped to the small city of Shenchow, from where they eventually continued their journey to Beijing, which passed without further incident.1

The plant collector was William Purdom, at the conclusion of a three-year expedition on behalf of the Arnold Arboretum and the British firm of James Veitch & Sons to northern and northwestern China and the Tibetan region of Amdo. In the course of his expedition, he sent to Boston 550 packages of seeds and well over one thousand herbarium specimens.2

~

Purdom, born in 1880, was a head gardener’s son from the Lake District in northern England. He served an apprenticeship with his father before working for two distinguished London nurseries, then joining the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, as a student gardener. The Kew course of training for botanists and horticulturalists was internationally renowned and correspondingly demanding to join and to pursue. Purdom had done well and had proved a particularly skilled propagator, especially of woody plants. But Kew’s director, Sir William Thiselton-Dyer, did not appreciate Purdom’s activism as the secretary of the Kew Employees Union, and in 1905, Purdom was dismissed for “agitation.” Purdom promptly petitioned the Board of Agriculture, Kew’s parent ministry, which agreed that he was perfectly entitled to join a trade union and ordered his immediate reinstatement. Thiselton-Dyer, unable to bear this humiliating public reversal, resigned. The new director, Colonel David Prain, then had to contend with the only strike there has ever been at Kew, efficiently organized by Purdom. All in all, it’s perhaps not surprising that when, in 1908, Charles Sprague Sargent enquired whether Kew could recommend someone to undertake a three-year expedition to China, Prain enthusiastically recommended Purdom as the very man for the job!3

Sargent had come to Britain in August 1908 to engage a plant collector to travel to northwestern China to collect plants and seeds for the Arnold Arboretum. Ernest Wilson, whom Sargent had sent to China in 1907, had made it clear that he would not extend his two-year contract.4 In 1906, Sargent had also agreed with the United States Department of Agriculture that Wilson would work in partnership with Frank Meyer, the department’s collector in China. Meyer, whose main interest was in plants of agricultural value, would also collect ornamentals in northern China, and Wilson would collect useful plants for the department in the southern zone. But Sargent was bitterly disappointed by how few ornamental specimens Meyer sent from Shanxi Province and was furious when these specimens were discovered to include several previously unknown species of larch (Larix), spruce (Picea), and pine (Pinus) from which Meyer, who had not recognized them as novelties, had not collected seed.5 Wilson, by contrast, was spectacularly successful, sending back thousands of herbarium specimens and large quantities of plant material, in the process enhancing the reputation of the Arboretum.

Sargent, a man of strong opinions and personal self-confidence verging on arrogance, refused to accept Meyer’s explanation that the north of China was “an utterly barren region”6 when it came to new ornamental woody plants and wanted to send a collector there to prove the contrary. Sargent also wanted this collector to harvest the botanical riches he was convinced were to be found in the high mountains of Shaanxi and Gansu Provinces in northwestern China. Sargent believed that, because the plants from that region endure harsh winters in their home range, they would be better able to stand the New England and north European winters than those from farther south. (The logic is seductive, and such plants will indeed withstand bitterly cold winters, but they are very vulnerable to late spring frosts, having evolved in a climate where spring is a brief prelude to a hot summer, a short transition from extreme cold to baking heat.)

Sargent asked Isaac Bayley Balfour, the regius keeper of the Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh, for advice in identifying a collector, and Balfour recommended George Forrest,7 who had, in the spring of 1907, returned from a very successful three-year plant-hunting expedition in Yunnan Province and whom Balfour knew wanted to return to China.8 Sargent suggested to his old friend Harry Veitch, whose family firm, James Veitch & Son, dominated the British horticultural trade, that they jointly engage Forrest and share the harvest he would send back from China.

Harry Veitch was agreeable, but although Forrest came to London in September to meet Sargent and Veitch, he refused their offer. Forrest was not impressed with the salary offered by Sargent and was reluctant to collect outside Yunnan, where he believed, quite correctly, that much more remained to be discovered. Nor would he agree to travel to China in early 1909 because he wanted to be at home for the birth of his first child in April. Sargent had to return to Boston in October, leaving Veitch to find a collector.

After two months during which Veitch failed to propose a candidate, Sargent wrote to him in early December reminding him of their agreement to send a collector in early 1909. After consulting Prain and the director of the Kew Arboretum, William Bean, Veitch offered Purdom the post at a salary of two hundred pounds a year plus expenses of four hundred pounds a year. Purdom asked for time to think about it before agreeing on January 7, 1909. Truth to tell, Purdom had little alternative but to accept Sargent and Veitch’s offer; his contract at Kew had expired, and he knew that his well-publicized (in Britain) record as a trade union activist—about which both Prain and Veitch appear to have maintained a discreet silence vis-à-vis Sargent—meant that most potential employers saw him as a troublemaker, a label which would have made it very difficult for him to find employment in Britain.

~

The first few weeks of 1909 passed in a blur, as Harry Veitch organized detailed briefings for Purdom on China. Purdom’s instructors included Sir Robert Hart, recently retired after forty-eight years in China as inspector general of China’s Imperial Maritime Customs Service, and Augustine Henry, the distinguished dendrologist who had spent nineteen years in China working for the Customs Service. The Kew-based photographer E. J. Wallis gave Purdom lessons in using a sophisticated glass-plate camera.9 Purdom sailed on the Oceanic from Southampton to New York on February 3 and reached Boston four days later. Sargent immediately formed a favorable impression of Purdom,10 and he spent Purdom’s second day in Boston writing an eight-page memorandum of guidance about where, when, and what to collect in China.

Sargent told Purdom that, on arrival in China, he should seek out Ernest Wilson in either Shanghai or Yichang (in western Hubei Province)11 before proceeding to Beijing. From there, he was to continue 120 miles north to Chengde (then often known as Jehol) and still farther north to the old imperial hunting ground at Weichang. In a characteristic display of wishful thinking, Sargent asserted that since Weichang “has never been covered by a botanist, it is not impossible that you will find many interesting and possibly entirely new plants.” Purdom was to leave Weichang in August so as to be in the Wutai mountain range, 180 miles southwest of Beijing in Shanxi Province, in mid-September, in time for the seed-drop of the conifers: obviously, Sargent especially desired seed from the new spruce, larch, and pine of which Meyer had sent herbarium specimens. Once the seeds had been collected, which Sargent thought “ought not to take very long,” he hoped that Purdom would return, via Beijing, to Weichang—a round trip of around six hundred miles—to gather seeds and herbarium specimens there.

The year 1910 was to be spent in Shaanxi Province, where Purdom was to seek “the wild tree peony” (Paeonia suffruticosa) before exploring the mountain range near Xi’an, the ancient former capital. This region is around five hundred miles southwest of Beijing. Finally, the third and last year, 1911, was to be spent in Gansu Province, in the high mountains on the border with Tibet, over one thousand miles from Beijing.

All this was spelled out by Sargent with admirable clarity, and he was equally clear about the principal object of the expedition, which was “to investigate botanically unexplored territory [and] to increase the knowledge of the woody and other plants of the [Chinese] Empire.” In pursuit of this last goal, Sargent expected Purdom to dry six sets of herbarium specimens for all woody plants, including specimens of the same species that might occur in different regions so as to show the extent of any variation. He also wanted Purdom to photograph “as many trees as possible,” including their flowers and bark, and “if time permits […] views of villages and other striking and interesting objects, as the world knows little of the appearance of those parts of China you are about to visit.”

These goals were not quite the same as those articulated by Harry Veitch, who had told Purdom “the object of your mission [is] to collect seeds and plants of trees and shrubs, also any plants likely to have a commercial value, such as lilies,” but there was sufficient overlap that Purdom felt he could satisfy both his sponsors. Purdom must also have welcomed Sargent’s brief acknowledgment that it might be impracticable to complete the ambitious itinerary he had sketched out in three collecting seasons and that Purdom might need, in the light of local advice or experience, to change it.

Sargent had his legal adviser draw up a contract, which he and Purdom signed. This stipulated that “all seeds of herbaceous, alpines and bulbous plants and all bulbs and other roots except those of woody plants” collected by Purdom would be the property of the firm of James Veitch & Sons and would be sent directly to them from China. Collections of woody plants would be divided equally between Veitch and the Arnold Arboretum. Photographs and herbarium specimens would belong to the Arboretum. The Arboretum would pay his salary and expenses in January and July, after which Veitch would reimburse one-half of the total sum involved.

Purdom spent a fortnight in Boston, mostly being taught how to prepare herbarium specimens. This involves pressing specimens of plants in blotting paper (also known as drying paper), including, as appropriate, the leaves, stems, flowers, fruit, and seeds. It is a long and laborious process, not least because of the need to change the absorbent paper every couple of days until the plants are thoroughly dried out. These specimens are subsequently mounted on cardstock with a note of the name of the plant, if known, the date and site of collection, and any details recorded by the collector that may be lost as a result of pressing and drying, such as color or scent.

After his training in Boston, Purdom traveled by train to Vancouver, from where he sailed for China on the Empress of Japan. He arrived in Shanghai on March 16, 1909.

~

Ernest Wilson had repeatedly made it clear that he would hold Sargent to their two-year contract and was not interested in extending it. Nonetheless, when Sargent wrote to him that he and Harry Veitch had engaged Purdom and hoped that Wilson would brief him before returning to London, Wilson expressed disappointment at being “passed over.” But he promised that he would do anything he could to help “your new man,”12 and his briefing of Purdom in Shanghai seems to have been reasonably cordial.

What is, however, clear from Purdom’s full account of his briefing from Wilson13 is that Wilson did not suggest to Purdom that it would be to his advantage to engage any of the eight trained Chinese collectors who had supported Wilson over the last three years. Their contract with Wilson would end as soon as they had finished packing the harvest of the last season’s collecting for shipment to Sargent. If Purdom had hired some or all of them, he would have benefitted from their experience and expertise in, for example, preparing herbarium specimens rather than having to train collectors himself, starting from scratch. The men themselves would surely have welcomed the continuation of their employment. Wilson’s reticence is all the more noteworthy when one recalls that when Wilson started on his first collecting expedition to China in 1899, he was briefed by Augustine Henry (who was leaving the country) and immediately thereafter hired Henry’s entire team, who had been trained over the previous decade.14 But Purdom lacked the experience to suggest he might do the same thing, and Wilson, despite his promise to Sargent that he would do all he could to help Purdom, did not propose it.

One wonders whether Wilson kept silent because he anticipated that he might return to China within the three-year period for which Purdom was contracted to collect for Sargent and Veitch. In fact, in June 1910, Wilson did return and promptly reconstituted his team of helpers. Obviously, this would have been impossible if the men had been in the field with Purdom. A less charitable alternative explanation is that Wilson was not especially keen to provide Purdom with assistants who might help Purdom challenge Wilson’s burgeoning reputation as the greatest of the Western plant hunters active in China.15 Certainly, in later years, Wilson quite deliberately burnished his reputation, including by rewriting some of the history of his first two expeditions.16

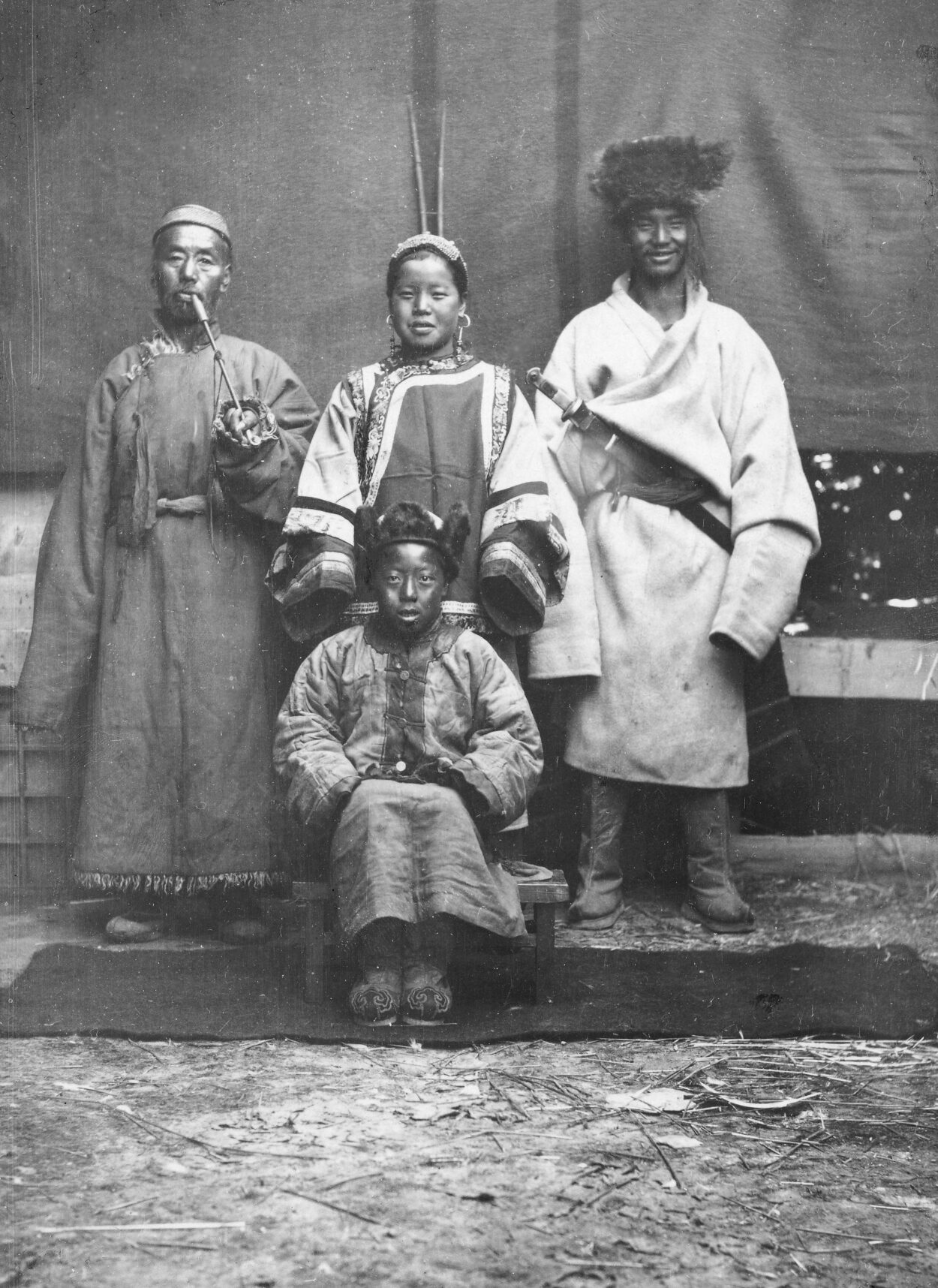

Immediately on his arrival in Beijing, Purdom applied himself to learning Mandarin Chinese, a language that he mastered remarkably quickly. Unusually for a Westerner in China at this time, Purdom consistently treated local administrators and farmers in the areas where he collected as his social equals, among whom he sought to make friends. Partly as a result, he was allowed into areas of China foreign travelers were actively discouraged from visiting, not least for their own safety.

Purdom spent the 1909 collecting season in northern China and Mongolia, including in Wutaishan. Sargent had specifically tasked Purdom with collecting seeds from spruce and larches found there, which were not in cultivation in the West, but the wet summer of 1909 meant that the trees did not set seed. Although Purdom sent cuttings and seedlings, Sargent complained that they had been poorly packed and that, as a result, many of them had died on the six-week journey to Boston.17 He was only partly mollified by seeds that were germinating in the Arboretum’s greenhouses. In fact, Purdom had dispatched thirty parcels of seeds and bulbs from more than three hundred unique collections to Boston and London that year. These included rhododendrons and primulas, a fine blue anemone, several peonies, and three species of clematis, one of which, the downy clematis (Clematis macropetala), has particularly graceful deep blue bell-shaped flowers. It first flowered in Veitch’s Coombe Wood nursery in 1912 and remains very popular today. For Sargent, there were several poplars (Populus), elms (Ulmus), larch, and herbarium specimens of a new form of bird cherry (later named Prunus padus var. pubescens forma purdomii), which is a small tree with copious white racemes, bright red berries, and fine foliage.

In April 1910, after overwintering in Beijing, Purdom traveled to western China. Sargent had asked him to investigate Moutan-shan (or Mudanshan, which translates to “peony mountain”) near the ancient city of Xi’an, where he hoped Purdom would find the original wild peony. When Purdom arrived, however, he found that the plants had long ago been harvested for traditional medicines and the mountain was stripped bare. Purdom took several photos of the mountain to leave Sargent in no possible doubt that there were no peonies (and few other plants) there. Purdom had better luck near Yan’an, where he found a wild population of the tree peony. He ultimately collected over five hundred seeds of this dark red peony, which was raised in both Boston and Coombe Wood. (Sargent would later write of this as a “first-rate achievement.”18) On Taibaishan, in southern Shaanxi, he found a fine rhododendron with dark pink buds shading into white flowers, subsequently named Rhododendron purdomii. He also found another wild population of the tree peony, but with no seed.

The next year, Purdom continued westward to Gansu Province and the Amdo region of Tibet. He found, in a monastery garden, a lovely winter-flowering viburnum (Viburnum farreri, then known as V. fragrans). He sent seeds to Veitch, who grew them on and subsequently sold his stock to Gerald Loder, the owner of Wakehurst Place in Sussex, where, in 1920, they flowered for the first time in Britain. Purdom also sent seed of an edible honeysuckle, Lonicera caerula, whose curious cylindrical fruit is today sold in the West as “honeyberry.” He ended the season in Minxian, in Gansu Province, where he had no choice but to wait for order to be restored following the anarchic violence that followed the Xinhai Revolution in October. Fortunately, Purdom had more or less completed the season’s collecting, which included several fine primulas and asters, and in December, he was able to persuade the Minxian authorities to provide (for a fee) an armed escort to enable him to return, via Honan, to Beijing.

When Purdom told the political staff at the British Legation about the attempted ambush near Shenchow, they were horrified to hear that he had killed three of the attackers, whom they strongly suspected (or they may have had confidential information confirming it as a fact) had been off-duty government soldiers.19 They urged Purdom not to repeat the story to anyone else lest he (and, by association, Britain) should be seen as taking up arms against the Chinese government. This advice suited Purdom, a very private man who throughout his life avoided personal publicity. Furthermore, Purdom was angling for a job with the Chinese Republican government and may well have believed that to publicize the shooting wouldn’t help his prospects. He did give Sargent and Harry Veitch very brief accounts of the incident,20 but it was not reported in either the Chinese or English press, nor did he ever allude to it in later life.

~

Both sponsors of the expedition were disappointed by Purdom’s harvest. Harry Veitch recognized that “if the plants were not there, then he [Purdom] could not send them,” but Sargent was reluctant to accept that while his decision to send Purdom to the botanical terra incognita of northwestern China had been a perfectly reasonable throw of the dice, the gamble had failed. That would have meant recognizing that Sargent had got it wrong, and he chose instead to blame Purdom for not trying hard enough.21

Sargent also rebuffed Purdom’s request to return home from Beijing via San Francisco and New York in order to enable him to visit Boston to explain why the results of the expedition had not matched Sargent’s over-ambitious hopes.22 And the statistics that Sargent reported in his 1910–11 Annual Report to the President of Harvard University tended (at least) to leave readers with the impression that Purdom’s harvest over the 1910 season had been less than one-quarter of Wilson’s, whereas, in fact, he had sent the Arboretum and Veitch germplasm from almost exactly half the number of different plants collected by Wilson in the same season.23

Sargent’s harsh judgment of Purdom’s competence as a collector may well have been influenced by his comparing Purdom’s collections with those of Ernest Wilson, sent from Sichuan Province. Such a comparison would prima facie not be to Purdom’s advantage: the two men were not competing on a level playing field. The climate of Sichuan is subtropical, shading into tropical, and the annual monsoon delivers plentiful rainfall. Gansu, Shanxi, and Shaanxi Provinces, where Sargent had dispatched Purdom, share a temperate climate, with bitterly cold winters and little rainfall. Unsurprisingly, the flora of Gansu and its immediate neighbors is much sparser than the vegetation of Sichuan where Wilson principally collected.

The Hengduan Mountains in western Sichuan illustrate the extreme biodiversity of the region where Wilson was collecting. The mountains are far enough south that during the last ice age they escaped being scraped bare by glaciers. The substantial variation in altitude created a range of habitats, from river valleys to alpine meadows and peaks, and a huge range of plants flourished there while those further north were wiped out by the ice. In consequence, the Hengduan massif is a biodiversity hotspot, a veritable plantsman’s paradise in which it is estimated there are over 8,500 species of plants, 15 percent of them endemic (found only in that confined geographical area). They include over one in four of the world’s species of rhododendrons (224 species), primulas (113 species), and mountain ash (Sorbus, 36 species)—the list goes on and on.24 In contrast, plant biodiversity where Purdom was collecting was much lower. In the Qilian Mountains of Gansu, researchers have tabulated around 1,044 species of plants, and in southeastern Gansu, the number is around 2,458 species.25

Neither Wilson nor Purdom ever claimed to have done more than explore part of the provinces in which they hunted for plants, but the bottom line is that Wilson was collecting in a region where there was approximately three and a half to eight times the number of plant species than in the area to which Purdom had been sent by Sargent and Veitch. This made it almost inevitable that Wilson would send back to Boston specimens and seeds of more species than Purdom. In 1910 and early 1911, the only season for which it is possible to make a direct comparison, Purdom sent back to Harry Veitch germplasm associated with 374 unique collections numbers, while Wilson sent back 744 collections, 271 of them collected by his assistants after he had broken his leg.26

Sargent’s negativity towards Purdom may also have been influenced by his feeling a measure of responsibility towards Wilson in respect of the avalanche that had nearly caused him to lose a leg and that left him with a severe limp.27 Wilson hadn’t really wanted to go on the expedition, but Sargent had effectively forced him to, and it seems quite possible that he subconsciously vented a feeling of guilt about what had befallen Wilson on Purdom.

Furthermore, the extent to which Wilson’s work in China captured the imagination of the United States media and public meant that Wilson found a ready market for the articles and books that Sargent encouraged him to write about his expeditions. Wilson stressed his links with the Arboretum in the publications, and his star status, in turn, added luster to the fundraising efforts in which Sargent was constantly engaged to support the Arboretum and its activities. In short, it suited both men very well for Wilson to be front and center of the public stage, and there is nothing to suggest that either of them was concerned that the accomplishments of other collectors, including Meyer and Purdom, were overshadowed as a result.

The final blow to any hopes Purdom entertained that this expedition might allow him to forge a reputation among the horticultural cognoscenti that would help him to secure a good job in Britain or the United States fell on his return to England. Harry Veitch had decided to close the firm, which had dominated the English nursery trade for decades, and sell the stock at auction, causing Purdom’s collections to be dispersed and brought to market without his name being associated with them (Viburnum farreri, mentioned above, is a particularly egregious example).

All things considered, if we factor in Purdom’s fundamental modesty and aversion to publicity, it’s easy to see why he never captured the public imagination in the way that, say, Wilson or Forrest did.

~

In 1912, Purdom began corresponding with officials in Beijing about a possible post in a yet-to-be-formed Chinese Forest Service, which would enable him to pursue an objective to which he was personally and strongly committed, namely the reforestation of China after decades of extensive and largely uncontrolled logging. There were long bureaucratic delays in setting up the service, and in 1913, when the alpine plant expert and plant hunter Reginald Farrer invited Purdom to join him on an expedition to northwestern China and Amdo, he accepted.28 He and Farrer botanized successfully in 1914 and 1915, collecting inter alios some fine poppies, alpines, primulas, and an elegant butterflybush (Buddleia alternifolia). Although Farrer would go on to write two of the best travel books of the era about the expedition,29 the devastating effect on European gardening and horticulture of the First World War and the complete collapse in demand for new plants brought an abrupt end to their plant hunting at the close of 1915.

In the spring of 1916, the Chinese government at last formally created a Chinese Forest Service, and Purdom was appointed as a senior forestry adviser to the Chinese government. Purdom must have been deeply happy at last to have achieved a senior management position in which he could make his mark. He began working with Han Ngen (Han An), the secretary of the Ministry of Agriculture, to train Chinese foresters, develop tree nurseries, and plant trees where they would do the most good. By 1919, after three years of backbreaking effort, over one thousand tree nurseries had been established in China, containing one hundred million young trees. In the same, year twenty to thirty million trees were planted on over one hundred thousand acres of otherwise unproductive land.30 Many of these were timber trees new to China, mostly from North America, which Purdom knew would do well in different Chinese regions and climatic zones. He organized the importation of many millions of seeds and cuttings, making him the only Western plant hunter to have imported into China vastly more plant material than he ever collected there.

It appears that eventually Purdom and Sargent were reconciled: in 1920 and early 1921, Purdom is known to have sent plant material to the Arnold Arboretum. Frustratingly, however, there is no surviving correspondence from this time in the Arnold Arboretum files, and Sargent’s personal papers are lost.

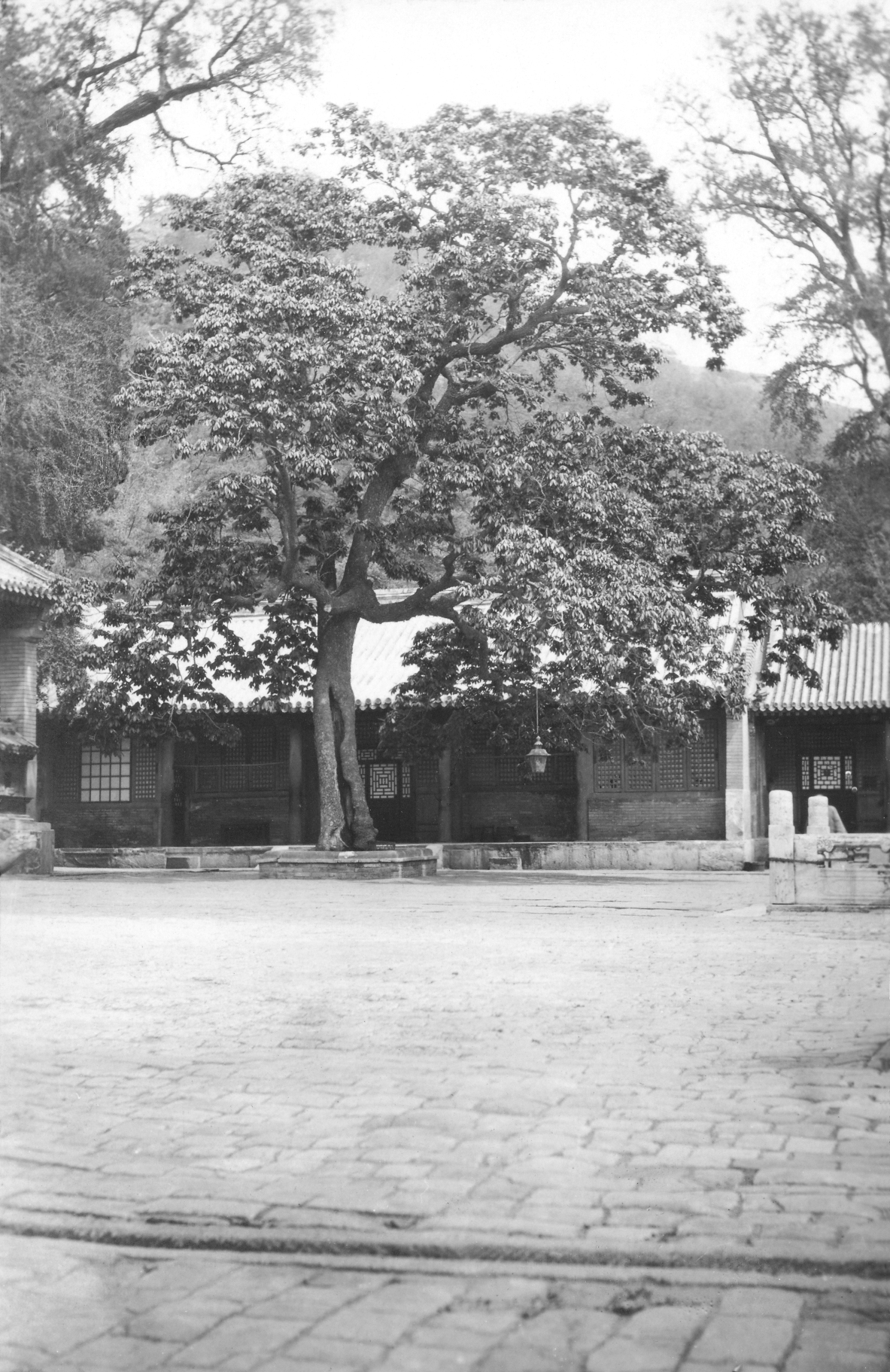

Purdom died suddenly in Beijing in November 1921 at the age of forty-one, due to an infection contracted following a minor surgery. He was buried in the English cemetery in Beijing, but fifty-four of his Chinese friends and colleagues clubbed together to commission a large and elegant memorial stele in the Forest Service plantation at Xinyang, which they renamed the Purdom Forest Park. Remarkably, the stele and the park were both left alone during the violently anti-foreigner Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s and they are both carefully preserved to this day. The epitaph is too long to quote in full, but a hundred years later the sorrow felt by Purdom’s friends who subscribed to the stele is still very clear. Perhaps what would have most pleased Purdom is their description of him as “a true and loyal friend of the Chinese people who won the admiration and respect of his colleagues, worked tirelessly for the reforestation of China and who, had he lived, would certainly have trained the next generation of Chinese foresters.”

Will Purdom was a fine and honorable man, who rose from a position of very limited personal agency and overcame formidable obstacles to leave the world a better place for his passage. Not only does he deserve to be remembered in his own right, but his life has a good deal to teach us about our place in this interconnected world. His concerns about protecting local ecosystems are a reminder that these ideas were current well over a hundred years ago. Finally, we should, in justice, remember him when we plant his introductions in our gardens: among them, “his” viburnum, butterflybush, or bird cherry.

Endnotes

1 Purdom letter to Harry Veitch, 23 March 1912 (copied by Veitch to Charles S. Sargent, 10 April 1912), Arnold Arboretum Horticultural Library, Harvard University (AA archive).

2 Anon. 1921. William Purdom. Journal of the Arnold Arboretum, 3(1): 55–56.

3 David Prain letter to Harry Veitch, 31 December 1908, Royal Botanic Garden, Kew, archives.

4 Ernest H. Wilson letters to Sargent, 21 November 1908 and 9 March 1909; also Sargent letter to Veitch, 26 April 1909, AA archive.

5 Sargent letter to Wilson, 8 July 1908, AA archive. Sargent also expressed his disappointment to David Fairchild, Meyer’s superior at the Department of Agriculture.

6 Frank Meyer letter to Wilson, 7 May 1907, AA archive.

7 Bayley Balfour letter to George Forrest, 26 August 1908, Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh archive.

8 George Forrest (1873–1932) made a total of seven expeditions to China, in the course of which he collected over thirty thousand different plants and herbarium specimens, nearly all of them from Yunnan Province in southwestern China.

9 Purdom was an apt pupil, and the Arnold Arboretum archive has a large collection of his photographs, which are an important resource for our understanding of remote areas of China in the first decades of the last century.

10 Sargent letter to Veitch, 16 February 1909; and to Prain, 25 February 1909, AA archive.

11 Sargent letter to Purdom, 8 February 1909, AA archive.

12 Wilson letter to Sargent, 9 March 1909, AA archive.

13 Purdom letter to Sargent, 26 March 1909, AA archive.

14 For a full account and a photo of the team, see: O’Brian, S. A. 2011. In the footsteps of Augustine Henry (p. 68 et seq.). Garden Art Press.

15 Wilson’s biographer, Roy W. Briggs, suggests that Wilson was concerned that his replacement by Purdom might be seen as an adverse reflection on the quality of his own work in China.

16 See, for instance: Holway, T. History or romance? Garden History, 46(1): 3–27.

17 Sargent letter to Purdom, 3 May 1910, AA archive.

18 Sargent letter to Veitch, 13 June 1912, AA Archive.

19 On March 10, 1912, the political department of the legation sent a telegram about the ambush to the Foreign Office in London, but unfortunately it has been “weeded” from the file in the Public Record Office. The legation also asked the representative of the London Times in Beijing, Ernest Morrison, not to report the incident, and Morrison complied.

20 In addition to the letter that Purdom sent to Harry Veitch cited above, see: Thomas, W. B. 1913, July 10. Creator of 2,000 new plants. Daily Mail, p. 3.

21 Frank N. Meyer letter to David Fairchild, 15 October 1912, USDA compilation of Fairchild correspondence held at the University of California, Davis, Vol. 3, pp. 1600–1601.

22 Meyer letter to Fairchild, 21 December 1912, USDA compilation, Vol. 3, pp. 1619–1621.

23 For my full accounting of this, see: Gordon, F. 2021 Will Purdom: Agitator, plant-hunter, forester (pp. 111–116). Royal Botanical Garden Edinburgh.

24 See: Kelley, S. 2001. Plant hunting of the rooftop of the world. Arnoldia, 61(2): 2–13. These figures are likely to have changed slightly in the intervening twenty years as new species have been identified and others have been reclassified. By way of comparison, the British Isles presently (2021) have 1,443 species from 308 genera, only 1.2 percent of them endemic.

25 Wang, J, Che, K., and Yan, W. 1996. Analysis of the biodiversity in Qilian Mountains. Journal of Gansu Forestry Science and Technology; also, Lu, W-Z. and Ren, J-W. 2005. Plant biodiversity and its conservation in Maijishan Scenic Regions of Gansu. Journal of Northwestern Forestry University, 20(4): 44–47.

26 Plant collecting is emphatically not a “numbers game,” and it would be foolish to use these figures to attempt to compare the relative efficiency of the two men. But Purdom clearly did a good job in a poor collecting area. Again, for my accounting of these numbers in the biography, see pp. 111–116.

27 For a full account of the story surrounding Wilson’s accident, see: Dosmann, M. 2020. A lily from the valley, Arnoldia 77(3): 14–25.

28 Purdom letter to Reginald J. Farrer, 9 September 1913, Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh archive.

29 See Farrer’s books On the Eaves of the World (1917) and The Rainbow Bridge (1921). Both books are dedicated to “Bill”, i.e. Will Purdom.

30 Reisner, J. H. 1921. Progress of forestry in China 1919-1920. Journal of Forestry, 19(4): 396.

The map in this article was inspired by the map on page 72 of Will Purdom: Agitator, Plant-Hunter, Forester and was created using Esri, Airbus DS, USGS, NGA, NASA, CGIAR, N Robinson, NCEAS, NLS, OS, NMA, Geodatastyrelsen, Rijkswaterstaat, Garmin, GSA, Geoland, FEMA, Intermap and the GIS user community.

Purdom Plants at the Arnold Arboretum

As of this writing, visitors at the Arnold Arboretum can find twenty-five trees and shrubs that arrived directly from Purdom (as seed) or Veitch (as plants) from Purdom’s first expedition to China. Another twenty-six plants represent other Purdom lineages, including Forsythia that originated from Purdom’s collections with Reginald Farrer. To map them in the landscape, visit https://arboretum.harvard.edu/explorer/. Use the advanced search and input “Purdom” in the collector field.

Francois Gordon retired from the British Foreign Office in 2009 after thirty years mostly spent in Africa. Today, he lives and gardens with his wife Elaine in Kent. His first book, Will Purdom: Agitator, Plant-Hunter, Forester, was published by the Royal Botanical Garden Edinburgh in 2021. It can be purchased on Amazon.

Citation: Gordon, F. 2021. William Purdom: The forgotten Arnold plant hunter. Arnoldia, 78(4): 24–37.

From “free” to “friend”…

Established in 1911 as the Bulletin of Popular Information, Arnoldia has long been a definitive forum for conversations about temperate woody plants and their landscapes. In 2022, we rolled out a new vision for the magazine as a vigorous forum for tales of plant exploration, behind-the-scenes glimpses of botanical research, and deep dives into the history of gardens, landscapes, and science. The new Arnoldia includes poetry, visual art, and literary essays, following the human imagination wherever it entangles with trees.

It takes resources to gather and nurture these new voices, and we depend on the support of our member-subscribers to make it possible. But membership means more: by becoming a member of the Arnold Arboretum, you help to keep our collection vibrant and our research and educational mission active. Through the pages of Arnoldia, you can take part in the life of this free-to-all landscape whether you live next door or an ocean away.