The Cultivated Herbarium Gives Scientists Another View of Arboretum Plants

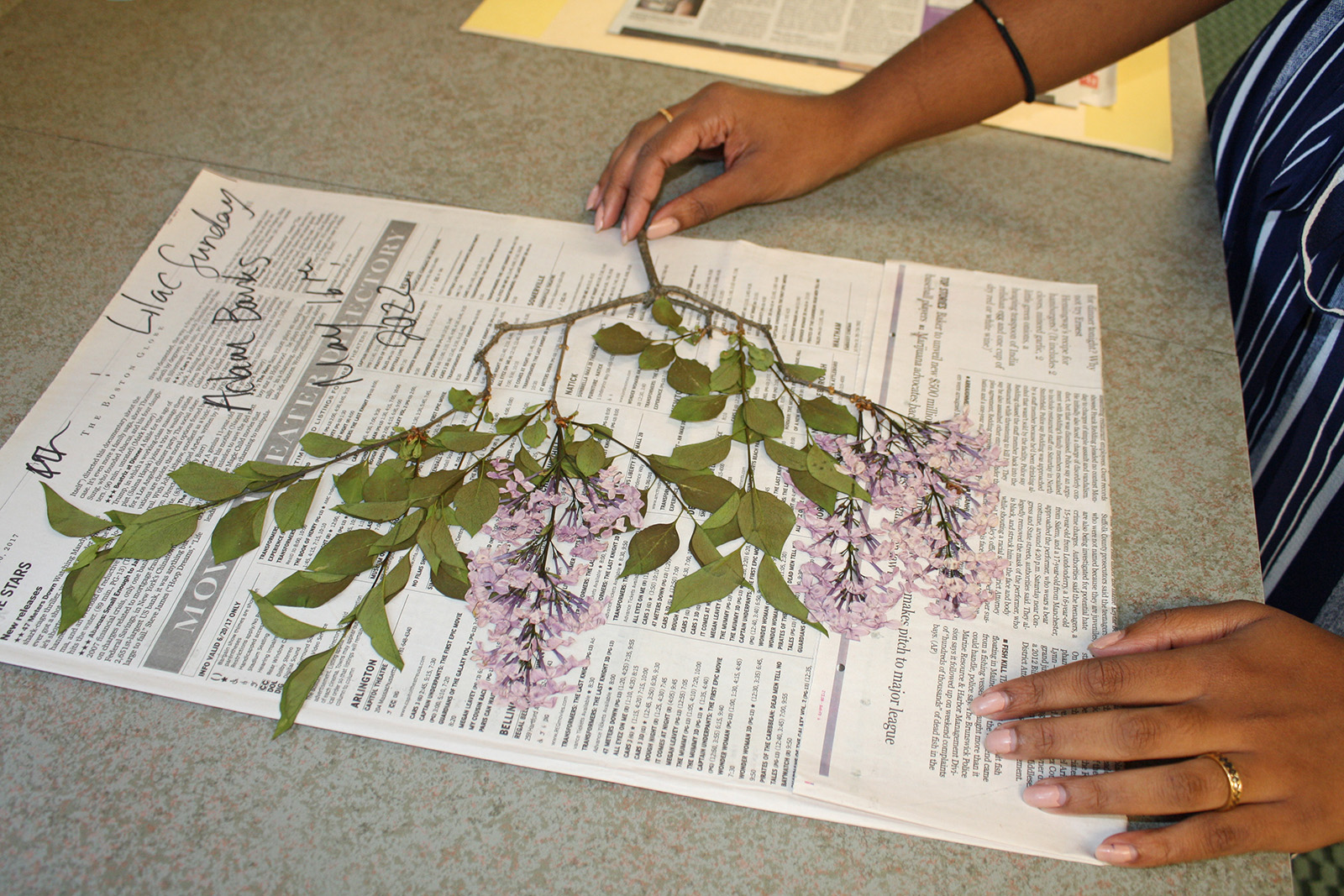

Carefully unfolding sheets of newspaper, I reveal tissue-thin dried blossoms of pressed lilac flowers, the rich purples and blues of their inflorescences faded to soft pastels. Despite the rigorous preservation process they have undergone, the powerful aroma of lilacs still permeates the air. The scent takes me back to the weeks leading up to the Arnold Arboretum’s annual celebration of Lilac Sunday, when I spent days collecting flower specimens while enveloped in their perfume.

Pressing plants for preservation—a leaf with bright fall color folded in a wallet, a flower from a gifted bouquet pressed in a heavy book—is a tradition as old as time. By the 1500s, the word “herbarium” was adopted to refer to a scientific collection of pressed plant cuttings mounted onto paper. Called herbarium vouchers at the Arboretum, these specimens preserve the genetic identity of plants and are useful as references for plant identification, species evolution, documentation of where plants grow over time, and even analysis of climate change. Once entered into our collection, these vouchers become part of the physical and historical record of the Arboretum, linking us to plants we grow today as well as those that lived here over time.

The Arnold Arboretum’s Herbarium of Cultivated Plants is one part of the larger herbarium of the Arnold Arboretum, which as a whole contains nearly 1.5 million specimens and is split between the main building of the Harvard University Herbarium in Cambridge and the Arboretum itself. Every one of the roughly 121,000 vouchers residing at the Arboretum comes from a plant of cultivated, rather than wild, origin. Though its primary focus is to document plants that have grown in the Arboretum’s living collections, it also includes thousands of examples of cultivated plants gathered from all over the world.

In 2022―to honor the Arboretum’s sesquicentennial and the return of Lilac Sunday after a two-year pandemic pause―I focused my collecting efforts for the Cultivated Herbarium on our renowned lilac collection. Known to science as the genus Syringa, lilacs are one of eight Nationally-Accredited Collections stewarded by the Arboretum in concert with the Plant Collections Network and the American Public Gardens Association. Even though our herbarium held an impressive 1,329 lilac specimens drawn from Arboretum plants, we found that some of our most prominent and historically significant cultivars such as ‘Purple Haze’ and ‘Lilac Sunday’ were not adequately represented. With the help of Conor Guidarelli, our horticulturalist responsible for the care and maintenance of the lilacs, we were able to complete a massive sweep of the plants, collecting flowering specimens in the spring and accompanying seed pods in early summer.

For each plant we cut a flowering branch, place it between sheets of newspaper, then nestle it into a plant press to compress the material and draw out moisture. After resting in a drier for a week, the cuttings are frozen at -30° Celsius for an additional week to kill off any insects or pathogens present. The delicate, dried cuttings are carefully mounted onto paper using glue, paintbrushes, tweezers, and a variety of other tools to create the vouchers. This is the most creative part of the process―arranging the flowers and leaves with care to create a beautiful work of art, in the hopes that it will last and be useful as a scientific specimen for hundreds of years.

Once a voucher is completed, it finds its new home within the herbarium. Typically, voucher sheets are secured in metal cabinets, which help protect them from pest damage. From there, a collection like ours can be organized in a variety of ways. Last year, I embarked on a complete reorganization of the Arboretum’s Cultivated Herbarium, switching from an old phylogenetic system of classification—which groups plants by their evolutionary relationships— to alphabetical order within their broader taxonomic groups for greater ease of access for anyone hoping to peruse our collection.

Historically, these kinds of collections have been sequestered with limited access to ensure preservation, but institutions like ours are increasingly able to share their collections through online databases. The vouchers associated with Arboretum plants have been scanned and uploaded online. Now that the reorganization of the Cultivated Herbarium is complete, I have begun the process of cataloging nearly 70,000 non-Arnold Arboretum vouchers. Through future grant support, we hope to complete the digitization of our entire collection and provide online access to these extraordinary specimens for study, whether for science, history, or the curiosity of plant enthusiasts around the world.

Much like journals, these vouchers have a way of conveying and preserving stories. Although their primary use is for research, herbarium vouchers can also tell us about the people who took care of these plants, the world they lived in, and how similar and different those are to our lives today. When I come across a lilac specimen, whether it is one I collected myself or from 100 years ago, it brings me back to those days of roaming through the seemingly endless clouds of flowers, looking for just the right ones to fill my plant press.