Sometimes trees get a bad rap. There’s the Whomping Willow of Harry Potter fame, the trees in Snow White’s terrifying Dark Forest, and our very own cucumbertree (Magnolia acuminata, 15154*D), which was recently described as grumpy, gnarly, and foreboding by several participants of Saturday’s Arboretum for Educators program. The topic was tree architecture and the goal to closely observe the growth habit of various trees at the Arboretum in order to discern some environmental factors that might be influencing specific forms. These observable characteristics comprise the phenotype of a tree, as opposed to the genotype, which is determined by its genetics or DNA.

By visiting pairs of the same tree—each growing under very different conditions—participants were able to understand how stark differences in phenotype can occur. For example, the cucumber tree located near the Arborway has plenty of access to light, space, water, and nutrients. Its massive form is a great example of a decurrent (rounded or spreading) growth habit. By contrast, an individual of the same species (49-2014*A) located on the slope behind the Hunnewell Building is somewhat crowded and shaded by neighboring white pines and exhibits excurrent (irregular or cone-shaped) growth as it reaches for the light before branching out to expose leaves to the sun.

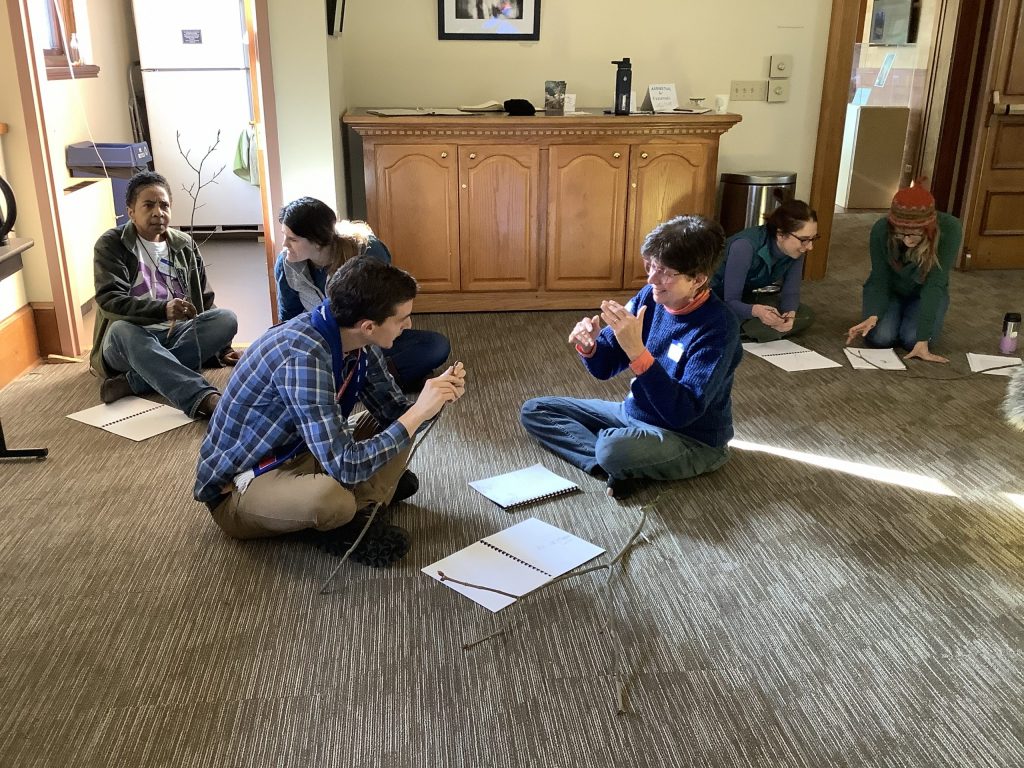

One powerful way to observe tree shape is by creating quick “gesture” sketches of trees in about 30 seconds. This allows the eye to focus on the most prominent forms, relative positions, and size of tree branches. With children, one could add the step of using the body to form the target shape and connect language to what is being observed.

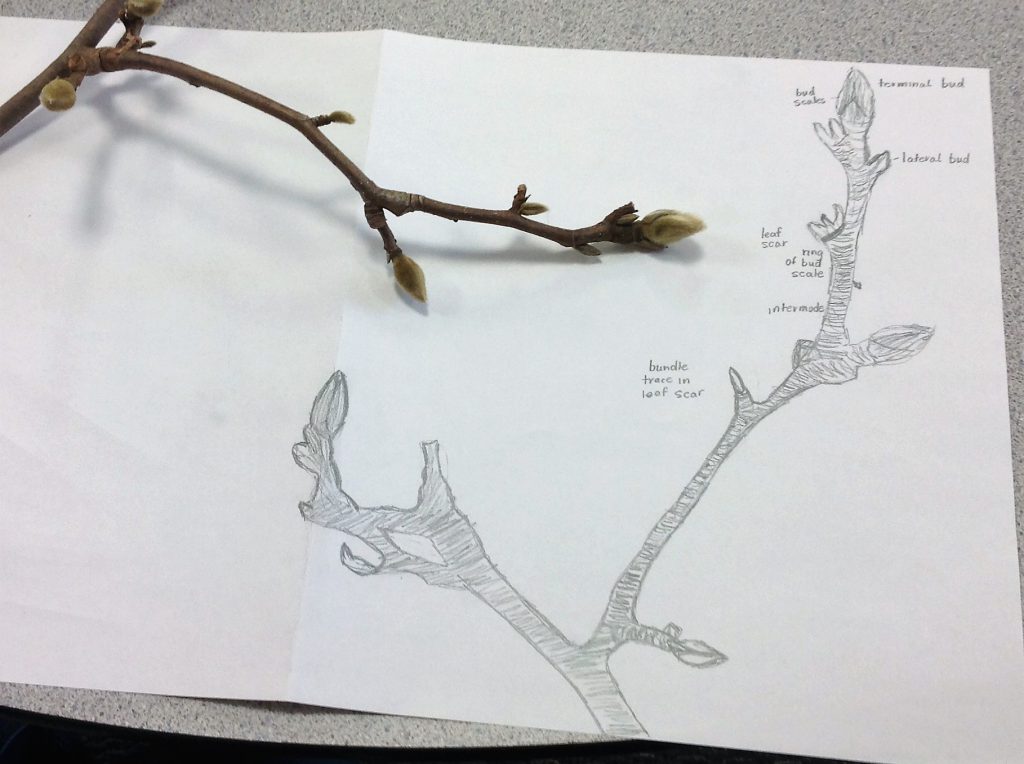

Another way to understand why trees have specific shapes is to learn about the physical arrangement of terminal buds, lateral buds, leaf scars, and terminal bud scale scars on a twig. A tree twig that has opposite leaf buds and clusters of buds on the tip (red maple, Acer rubrum) will develop differently, and therefore be shaped differently, than a twig with a large sticky terminal bud and alternating leaf buds (horsechestnut, Aesculus). When observing and drawing twigs, it is best to use a hand lens and large paper in order to capture details on a life-size scale. Children can even be encouraged to trace the shadows of the twig when drawing under a strong light to jumpstart the drawing process.

Understanding why trees are shaped the way they are can go a long way to changing a tree’s bad rap!The Arboretum for Educators events aim to introduce seasonal, natural phenomena to teachers and model ways in which students can engage in outdoor learning. Programs are designed to illustrate how teachers can bring that learning back to their classrooms for further investigations. Please join us at our next month’s free event, Tree Study part 2: Inside and Outside Trees.