After mentioning plant collecting in China, we often get the question: “Why there?” Well, some 30,000 species are native to the Middle Kingdom, many growing in temperate climates quite similar to that of New England. Illustrating this point is that among the Arboretum’s wild-collected plants, over 25% hail from China, second only to the United States’ share of 35%. Thus, as we collect species as part of the Arboretum’s ambitious Campaign for the Living Collections, China remains a premier destination. This year’s expedition, under the auspices of the North America-China Plant Exploration Consortium (NACPEC), took us 7,500 miles away from Boston to northern Sichuan province, a region explored by Ernest Henry Wilson over a century ago. Our trip (15 September to 1 October) combined plant hunting and specimen processing, with relationship building and fantastic Sichuan cuisine.

Prior to our formal expedition, we first spent a few days at Hunan’s Provincial Forestry Botanical Garden in Changsha, which allowed us to adjust to the 12-hour time difference and enjoy the warm-temperate flora found in a USDA Hardiness Zone 9 climate—nothing like seeing massive camphor trees (Cinnamomum camphora) functioning splendidly as street trees. In addition to Michael giving a seminar to their scientists and staff, we met with officials to discuss future collaborations related to staff and plant exchanges.

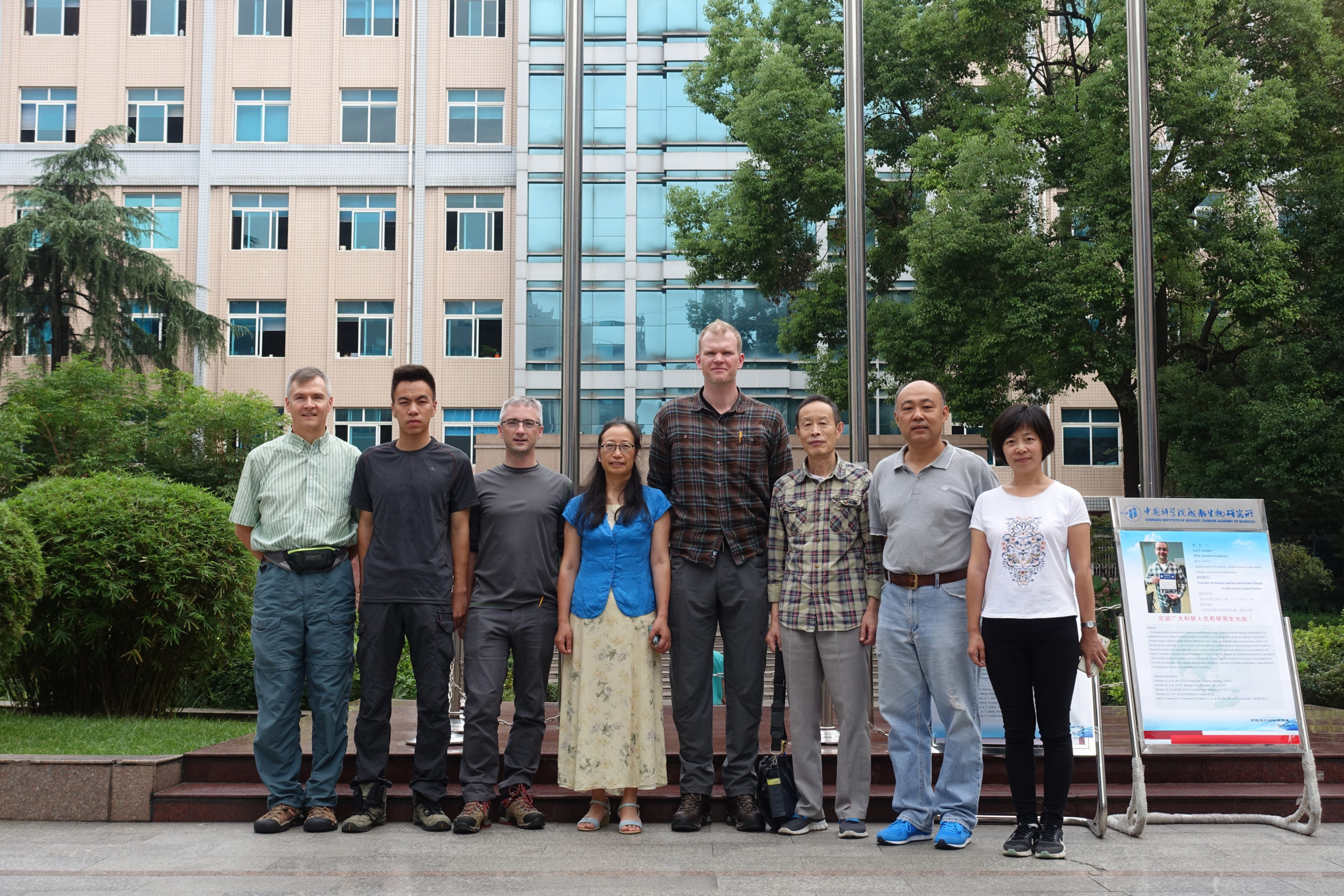

On the 19th we flew to Sichuan’s capital of Chengdu to join our assembling expedition team before heading north the next morning. Kang Wang and Jian Quan represented Beijing Botanical Garden, and Huaicheng Li from Chengdu’s Institute of Biology rounded out the Chinese contingent. Kang has been an instrumental ally of NACPEC, having participated in seven previous expeditions. As always, we were grateful for his logistical ability and botanical prowess. The final member of our team was Jonathan Shaw of Harvard Magazine, who was there to document the Arboretum’s activities in China and proved to be the ablest of field hands.

Much of our collecting took place on steep mountain slopes and river valleys near Si’Er in Pingwu County, accessible via one-lane gravel roads, many of which were in the process of subsiding into the rivers below due to the season’s inundating rainfall and occasional earthquakes. On a typical day, we would drive until the roads closed—or where prudence dictated it was safer to walk—and then hiked and bushwhacked along trails, through bamboo thickets and terrestrial leeches. At other and often more effective times, we hiked and collected beside roads to access the open-grown vegetation that was growing up- and down-slope to either side of us.

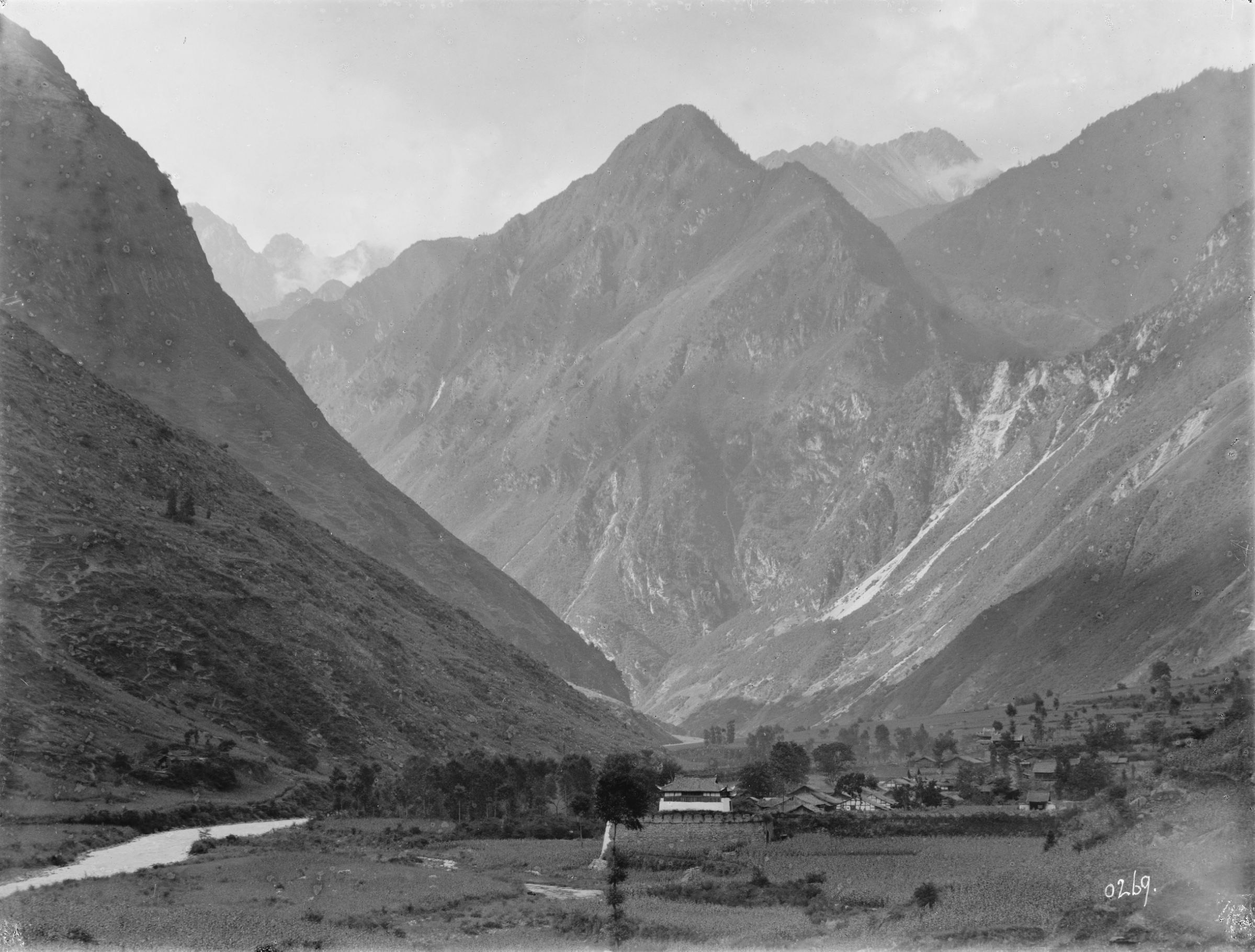

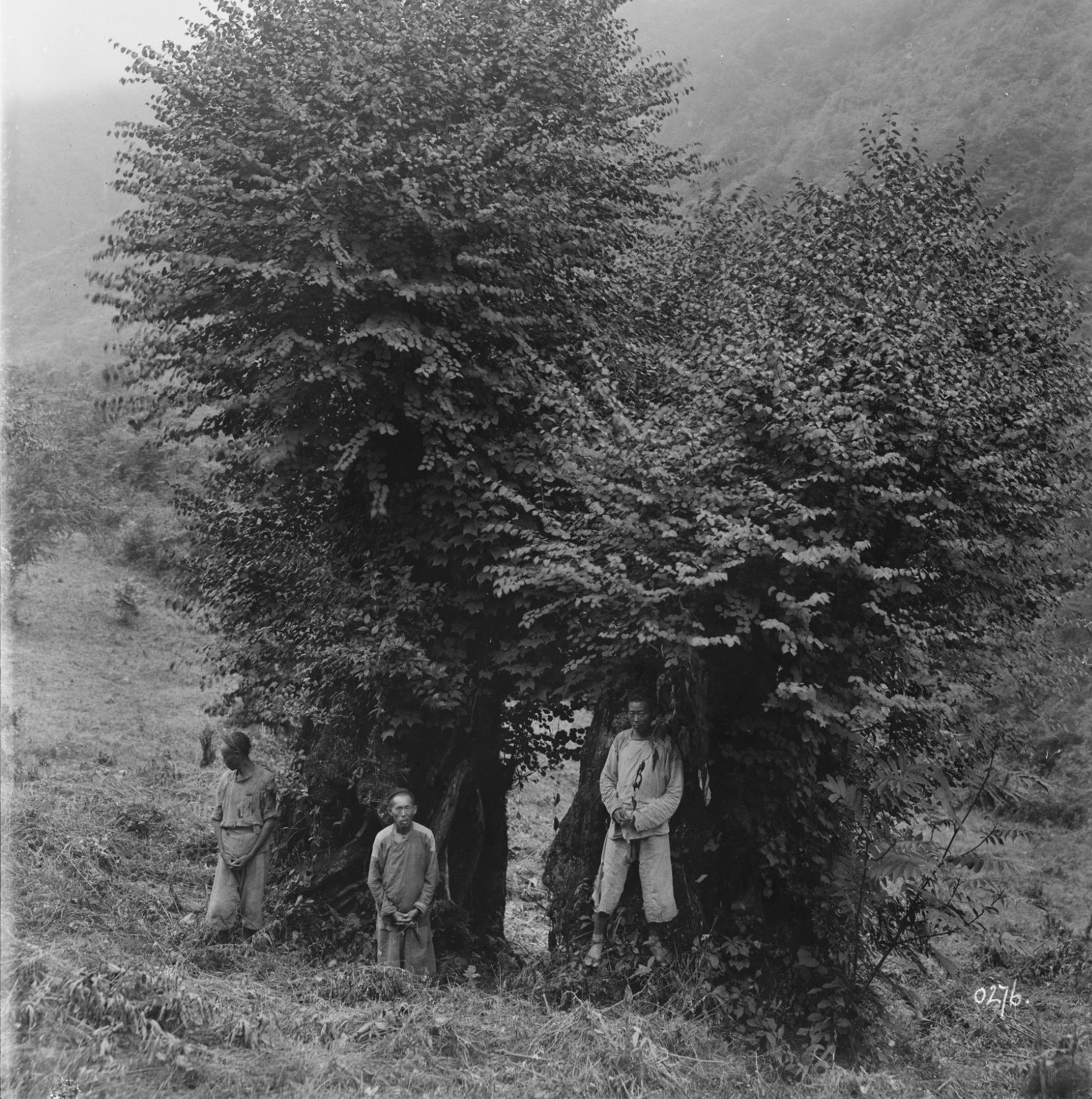

On one memorable day, we set our sights on Dupingba, a nearby valley known for its woody plant diversity, spectacular views, and history of exploration by Wilson, who passed through the same region in 1910. In particular, we were making a pilgrimage to see several ancient katsura-trees (Cercidiphyllum japonicum) that Wilson photographed. At the time of his visit and collection of specimens (Wilson No. 4301), he described the area as “open country” and the photograph (below) clearly shows two large stumps (likely coppiced for firewood) recovering under full sun. After a death defying trek up the mountain in our vehicle (holding our breath as we drove over washouts), we parked and hiked for a few more hours along the condemned roadway. Our team then went off road, ascending several steep gullies and streambeds until we came to a low meadow ringed by a dozen mature Cercidiphyllum that were starting to develop their characteristic buttery gold fall color.

However, these gorgeous specimens were not our goal. Another plunge into a wooded and wet depression soon revealed what we had come to see: the largest mass of trunks and stems of any Cercidiphyllum any of us had ever witnessed. The tree(s) that had been about 8 m (25 ft) tall in Wilson’s time were now over 20 m (65 ft), having not only doubled in height but sent out countless new basal suckers that had themselves become large specimens. The largest stem, hollowed out yet still functioning, had a diameter at breast height of just under 2 m. It was a time for all of us to marvel and genuflect, to see and touch the exact same tree that Wilson had. And, we were in luck as the large beast of a tree was bearing the small green banana-like fruits attached to short-shoot spurs. A combination of Andrew’s height and pole pruners finally guaranteed our access, and after gathering ample seed and herbarium collections, and countless photos, we joined Kang to recreate Wilson’s photograph. We made sure at least one of the images (below) was genuine, with Kang looking off to his right just like one of Wilson’s teammates had in 1910.

The day’s excitement wasn’t over—we still had several notable collections left to make, including several birches and the dove tree, Davidia involucrata. However, what may prove to be the most significant collection of the trip was of a beech. On the way up, Michael had took note of several massive, multi-stemmed and low-branching trees that upon further investigation proved to be Chinese beech (Fagus engleriana). Wilson collected this exemplary and elusive species in 1907 in Hubei province, and it is likely that most if not all living germplasm outside of China can be traced to this single introduction. The fates were shining brightly upon us, for one of the trees we saw bore fruit and after several attempts, we were able to make a modest collection. What excitement indeed!

All told, by the end of the trip, we made almost 40 collections from these and other memorable species such as Oliver maple (Acer oliverianum), giant dogwood (Cornus controversa), Mongolian hydrangea (Hydrangea bretschneideri), wingnut (Pterocarya macroptera), and Chinese hemlock (Tsuga chinensis). We cannot wait to watch them matriculate through our greenhouses and nurseries, and eventually site them into the permanent collections where we and others can watch them mature. And, who knows, perhaps in another 100 years, our successors will return to northern Sichuan to follow our—and Wilson’s—footsteps.