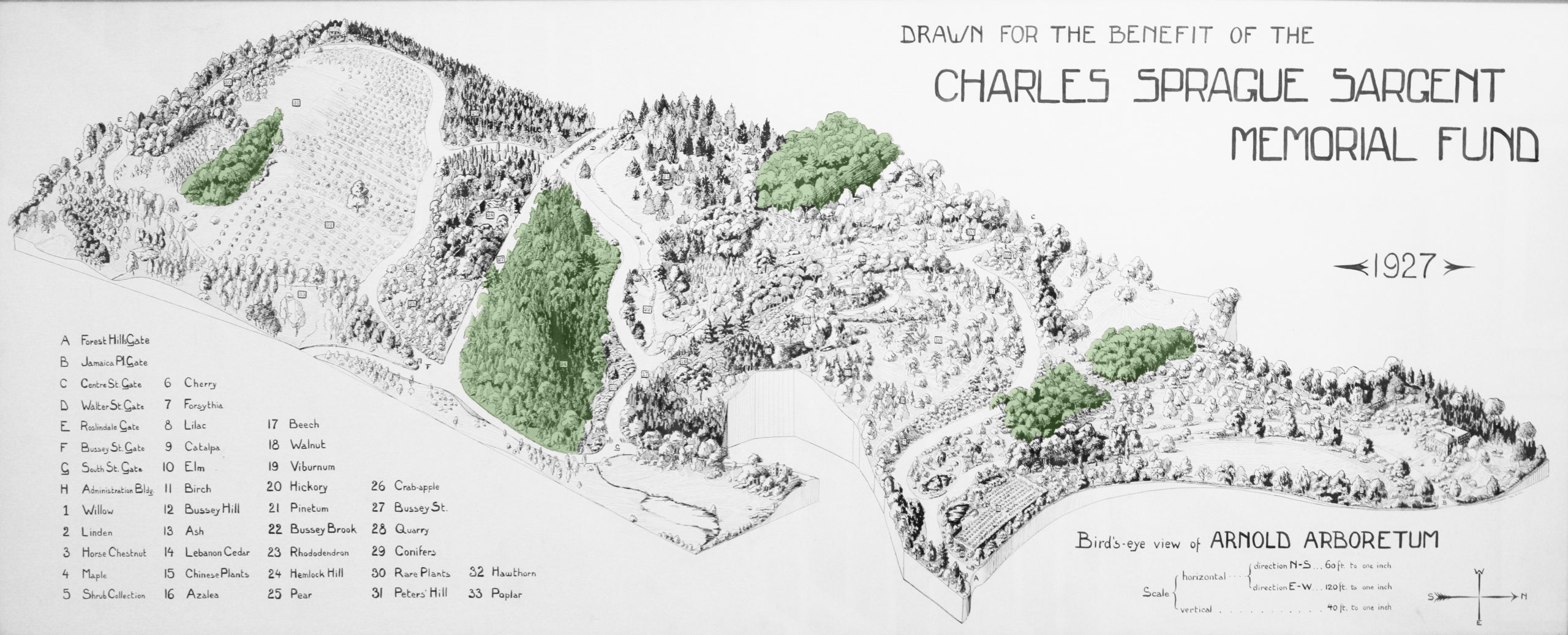

At the heart of the story of the Arboretum’s woodlands lies a tension between the managed and the unmanaged, the natural and the constructed. From the beginning, the Arboretum’s woodlands were intentionally excluded from formal development to serve as an aesthetic contrast to the taxonomically grouped collections. The Arboretum’s first director, Charles Sprague Sargent, took careful inventory of the remnant woodlands included in the Arboretum’s indenture. Rather than clear these areas for collections, Sargent, in concert with the landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, preserved these masses of native trees, noting their natural beauty and educational potential. “In no other public garden are there such cliffs or a more beautiful remnant of a coniferous forest,” Sargent wrote of Hemlock Hill, one of the four main Arboretum woodlands. Of the other areas, he noted that large oaks and other deciduous trees—some more than two-hundred years old, according to his estimate—were valuable for illustrating “New England trees in their adult state.”

Since Sargent’s time, these four areas—North Woods, Central Woods, Hemlock Hill, and Peters Hill Woodland—have come to exemplify the concept of the “urban woodland,” providing benefits along with management challenges unique to urban forest fragments. Today, these woodlands provide a naturalistic backdrop to the cultivated collections, offering a sense of spontaneity—whether in a fleeting glimpse of wildlife, discovery of a rare wildflower, or an unexpected encounter with a venerable old tree. Despite the seeming wildness of these areas, the woodlands and the ecosystems they support hardly represent the sort of pristine New England forest we might imagine them to be. On the contrary, they exist at the intersection of the intended and unintended consequences of human decisions—a sustained biological triumph over repeated broad-scale disturbances, creating a colorful mosaic of the native, the non-native, and the outright invasive, while raising questions about the very definition of so-called natural woodlands.

Woodland Hill

The woodlands inherited by Sargent at the time of the Arboretum’s founding in 1872 bore the marks of widespread ecological disturbance, most of it regrown from worn cropland and pasturage. In a 1935 article on land-use history at the Arboretum, research assistant Hugh Raup (who would later be appointed the first plant ecologist on the Arboretum staff) examined deeds of conveyance, records of will, and other historical documents to catalogue the extensive parceling and transfer of properties that would eventually form the Arboretum. From Raup’s historical rendering, we know with some certainty that during colonial settlement in the 1700s, the forested portion of the Arboretum’s lands befell the same dramatic ecological disturbance as most central New England forests. Rapid deforestation provided fuel and lumber; clear-cut land with fertile soil was cultivated; and upland areas with thin, rocky soils provided pasturage and orchard land.

During that period, much of the Arboretum acreage passed through generations of the Davis, Morey, and Weld families. Raup used dendrochronology (a method of tree-ring dating) to show that nearly all of this land—with the exception of the steep slopes of what would later become known as Hemlock Hill—had witnessed the wholesale removal of mature trees. Early on, a saw mill had even been constructed on Bussey Brook. Then, in 1806, a wealthy merchant named Benjamin Bussey began purchasing properties in the area. He consolidated the land into an exemplary pastoral estate known as Woodland Hill, on which he would spend his well-earned retirement. Bussey was fascinated by horticultural and agricultural science, and among his three hundred acres of hillsides, meadows, ravines, and brooks, the retired merchant reared merino sheep and cultivated the land through the introduction of novel crop species, trees, and shrubs.

Bussey developed his country estate in accordance with the naturalistic English landscaping tradition that had recently permeated American design sensibilities. He targeted areas for reforestation as part of his landscape plan and opened his woodlands, in truly altruistic fashion, to any who wished to escape the bustle and din of nearby Boston. Margaret Fuller and her circle of transcendentalist thinkers visited Bussey’s Woods, now known as Hemlock Hill, and she wrote fondly of the soaring hemlocks and pines found along the brook. Despite the rhapsodic reflections inspired by these woodlands, Raup’s study of extant trees in 1935 suggests that the oldest hemlocks were scarcely older than thirty when Bussey acquired the hill among his first parcels and, hence, would have been little more than twice that age when Fuller became a frequent visitor.

Bussey’s stewardship marked a period of rejuvenation for woodlands on the property, yet the ecological succession was nonetheless dictated according to the management practices of this genteel landowner. One local historian, drawing on the memory of older residents in 1897, noted that during Bussey’s tenure, woodland paths had been carefully tended all over Hemlock Hill and that an arbor had been erected near the summit, allowing visitors to reflect on the pastoral vista. This aesthetic approach to landscape maintenance was also outlined in Bussey’s will, where he dictated that, as long as his family still occupied the land following his death, no trees should be removed, except when necessary “for the beauty of the groves and the walks.” Presumably Bussey would have applied a similar approach to other woodlands—or rather thickets of young trees—as he acquired them. The areas now known as Peters Hill Woodlands and the North Woods were primarily ten to fifteen years old when Bussey died in 1842, while the Central Woods—located on rocky soil that was largely unsuitable for agriculture—was between twenty-five and fifty years old.

In 1930, nearly a decade before the hurricane caused ecological upheaval across New England, Arboretum botanist Ernest Jesse Palmer presented an extensive survey of the Arboretum’s spontaneous flora, cataloging biodiversity throughout much of the grounds—including its woodlands. Alongside his thorough inventory of each area of the living collections and the underlying geology of the landscape, Palmer hinted ominously at the effects of aggressive exotic plants on native flora. His account is particularly notable for its description of the colonization of highly disturbed areas, such as the abandoned quarry south of Bussey Street, by an “uncommon” assemblage of herbaceous weedy species like green foxtail (Setaria viridis), black nightshade (Solanum nigrum), and common vetch (Vicia sativa). These species, notably absent from his inventories of the diverse and richly populated woodland areas, had only begun to take hold on the grounds. The time between Palmer’s and ours marks an ecological transition for many of the Arboretum’s natural areas, with the slow creep of invasive plants gradually shifting the compositions of species among these woodland fragments.

Most of the first weedy species to show up in New England arrived with European settlers beginning in the seventeenth century. Well-adapted to continually disturbed conditions, many of these species established themselves in parts of the Arboretum. A second wave of non-native introductions arrived on a network of exploration and plant trade connecting Western nurseries and botanical institutions with East Asia beginning in the 1860s, resulting in the rapid importation of thousands of potentially invasive species. Through its legacy of collection and distribution of exotic plants, the Arboretum played its part in popularizing many of these species, such as Oriental bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus) and Amur cork tree (Phellodendron amurense).

Survey methods

Woody flora was documented in a 2017 survey, based on two randomly assigned ten-meter-radius circular plots within each of the four woodlands. In Peters Hill Woodland, only one circular plot was examined along with a recreated transect first studied by the Hunnewell interns, class of 2008.

In addition, each study area was sampled as part of the 2017 landscape-wide soil survey. Ten auger samples, separated into A and B horizons, were taken within each of the four study areas and composited, producing one A- and one B-horizon sample for each natural land. These samples were sieved, air-dried, and sent to the University of Massachusetts for analysis.

References

Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University. 2011. Landscape management plan (3rd edition). Retrieved from https://www.arboretum.harvard.edu/ wp-content/uploads/AA_LMP_Summary.pdf

Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University. 2007. Cultural resource management plan. Arnold Arboretum Horticultural Library, Harvard University.

Bussey, B. 1859. Will of Benjamin Bussey of Roxbury. Boston: J.H. Eastburn’s Press.

Del Tredici, P. 2010. Spontaneous urban vegetation: reflections of change in a globalized world. Nature + Culture 5(3): 299.

Hay, I. 1995. Science in the pleasure ground: a history of the Arnold Arboretum. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Hay, I. 1994. George Barrell Emerson and the establishment of the Arnold Arboretum. Arnoldia 54(3): 12–21.

Mathewson, B. 2007. Salamanders in a changing environment on Hemlock Hill. Arnoldia 65(1): 19–25.

Olmsted, F.L. 1982. To Charles Eliot Norton, 5 May 1880. In R. C. Wade (Ed.), The papers of Frederick Law Olmsted: parks, politics, and patronage (pp. 463–465). Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Palmer, E.J. 1930. The spontaneous flora of the Arnold Arboretum. Journal of the Arnold Arboretum 11(2): 63–119.

Raup, H.M. 1935. Notes on the early uses of land now in the Arnold Arboretum. Bulletin of Popular Information (Arnold Arboretum, Harvard University) 3(9–12): 41–74.

Sargent, C. S. 1875. A few suggestions on tree-planting. Twenty-Third Annual Report of the Secretary of the Board of Agriculture. Boston: Wright and Potter, State Printers.

Sargent, C. S. 1922. First fifty years of the Arnold Arboretum. Journal of the Arnold Arboretum 3(3): 127–171.

Citation: Schissler, D. 2018. Great wild gardens: The story of the Arboretum’s woodlands. Arnoldia, 76(1): 18–31.

Sargent, C.S. 1880. To the Board of Park Commissioners, City of Boston. Fifth annual report of the Board of Commissioners of the Department of Parks for the City of Boston for the year 1879 (pp. 21–22). Boston: Rockwell and Churchill, City Printers.

Sargent, C.S. 1885. To Frederick Law Olmsted, 5 February 1885. Charles Sprague Sargent (1841–1927) papers, Arnold Arboretum Horticultural Library, Harvard University.

Schulhof, R. 2008. Ecosystems in flux: the lessons of Hemlock Hill. Arnoldia 66(1): 22–28.

Whitcomb, H. M. 1897. Annals and reminiscences of Jamaica Plain. Cambridge: Riverside Press.

Wilson, M.J. 2006. Benjamin Bussey, Woodland Hill, and the creation of the Arnold Arboretum. Arnoldia 64(1): 2–9.

Daniel Schissler is Associate Project Manager at the Arnold Arboretum, a former research assistant in the Friedman Lab, and a former Isabella Welles Hunnewell horticultural intern, class of 2016. He holds an MFA in photography from Massachusetts College of Art and Design and a BA in architectural studies and archeology from Tufts University.