Municipal parks are the last territory of the decorative gardening tradition of bedding out: the practice of using brightly colored, low-growing flowering and foliage plants in ornamental patterns in beds, mounds, pyramids, floral clocks, commemorative plaques, and three-dimensional figures. Arranging plants to create decorative patterns is a convention of garden design from the eighteenth century, found from the parterres de broderie of Versailles to the boxwood fleur de lis of George Washington’s Mount Vernon garden. But in the nineteenth century, perhaps as a reaction to the long reign of the picturesque model, which favored naturalistic design, bedding out jumped the walls of the aristocratic garden and found a home in public parks on both sides of the Atlantic. The bedding out practice elicited the admiration of the public and the sustained scorn of many landscape critics.

A variety of names have been assigned to this practice: carpet bedding, mosaiculture, pattern gardening, “gardenesque.” It is also called Victorian gardening, an homage to its popularity in nineteenth century Great Britain, where advances in greenhouse technology and the introduction of tropical and subtropical species created a new way of displaying flowering plants. Bedding out, now the shorthand term, occupies a territory between art and craft. It is part of the history of ornamentation as well as the history of gardening. Both embrace the power of serial imagery and the creator’s virtuosity in creating original forms. Bedding out evoked heated discussion on the definition of taste: what is it, who has it, and who doesn’t. Bedding out of brightly colored flowers in artificial situations became part of the larger discussion in which popular taste was defined as bad taste, the highbrow/lowbrow remnants of that discussion still being argued in gardening circles today. Bedding out was the territory of gardeners rather than landscape designers, anonymous individuals whose skills were admired but whose names are unknown. The great bedding out schemes in public parks in American cities were associated with civic pride, with a populist enthusiasm for both the intricate floral displays and the intensive labor that was needed to both create and maintain them. Horticulture, as well as city beautification, is inherently competitive. Supported by park commissioners and local officials, municipal gardeners were encouraged to expand their floral displays to accommodate the tastes of the people—“to show you care.”

Bedding out is temporary and labor intensive—a sink-hole of energy consumption. It is profoundly artificial, appealing most directly to the senses rather than to the power of reflection or solitary contemplation. It is not a simulacrum of nature. It is antithetical to a prevailing notion of public parks based on a pastoral model, famously invoked in Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvin Vaux’s design for Central Park in New York. It did not claim to bring the country into the city. The practice of bedding out produced no theoretical treatises, no literary or painterly allusions. It tapped into the public’s love of spectacle and novelty, its appreciation of skilled labor well executed. Bedding out captured the lure of the exotic by using newly discovered plants from South America and Africa, tropical and subtropical natives brought into a temperate climate. It had the repetitive power of a military parade, an analogy not lost on the British garden writer William Robinson, who observed “Gardeners were not so much plant stewards as drill sergeants.”

Critics of this type of floral display reached new heights of rhetorical disdain. William Robinson went on to call bedding out “pastry-making.” The popular and widely published British writer Shirley Hibberd called ribbon beds (long meandering beds with alternating bands of floral color) “eels in misery.” Landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted’s antipathy to floral display is well known. Writing in 1892 to his associates in Brookline, Massachusetts, about detached floral beds in London parks, he observed “I have hardly seen anything yet of that kind that did not seem to me childish, vulgar, flaunting, or impertinent, out of place and discordant with good general effect.” In an article in a 1908 issue of Ladies Home Journal, the writer blamed municipal gardeners for creating “veritable pimples on the face of Nature.”

The Roots of Bedding Out

The evolutionary process that advanced the nineteenth century version of bedding out is traced to the writings of landscape designer and writer John Claudius Loudon (1783–1843) who, in the 1830s, introduced the word “gardenesque” to the vocabulary of landscape. He encouraged his readers to think beyond the picturesque to what he defined as “scientific,” collecting plants from all over the world to test their adaptability to different climates and growing conditions (a close definition of arboreta and botanical gardens). The goal was not to imitate nature. While Loudon valued artifice and offered bedding designs in many of his publications, he did warn against the extremes of bedding out, the distorted beds and clashing colors.

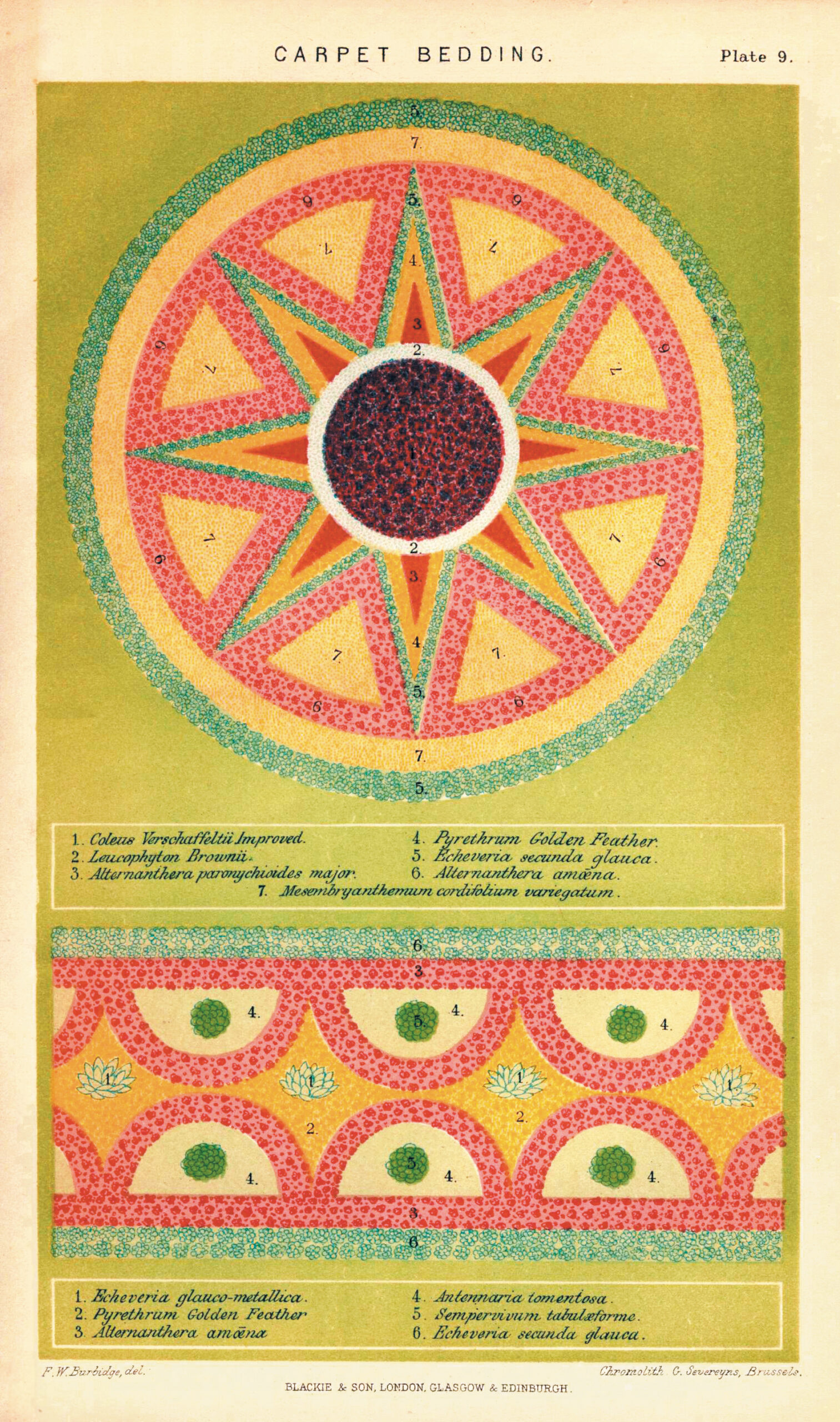

Loudon also recognized the limited educational opportunities for gardeners whose only option was a long apprenticeship that isolated them from new plant introductions and planting techniques. Loudon published Self Instruction for Gardeners in 1815, the first of several publications in the nineteenth century that attempted to codify best practices for both estate gardening and later municipal park management. With printing costs dropping, a number of magazines were founded that addressed professional gardeners, giving them access to information on new bedding plants and propagation techniques. They came to serve as pattern books for floral designs—fashion magazines for aspiring enthusiasts. Florists’ Journal, Gardeners’ Chronicle, and Gardener’s Magazine were available in Great Britain, and Magazine of Horticulture, Gardener’s Monthly, Genesee Farmer and Gardener’s Journal informed gardeners in the United States.

If principles of romanticism and aesthetic theory provided a structure for the pastoral park, advances in science and technology stimulated the expansion and complexity of bedding out. To underscore the artificiality of the bedding out system, the plant species used were often imports from South America, Africa, and the Mediterranean region. The botanical bounty collected by plant explorers, perhaps more appropriately called flower hunters, was given to botanic gardens and to commercial nurseries where species were hybridized to create showy selections with features such as compact growth, larger flowers, more brilliant colors, and variegated foliage. Plants were as much a product of the nursery trade as they were of plant collecting. Many global imports—begonias, calceolaria, echeveria, caladiums, cannas, coleus, and more—were commonly used in bedding out configurations. Sedums, sempervivums, and other succulents also had a brief period of popularity. Palms, yuccas, crotons, monkey puzzle trees, and banana plants, all valued for their exotic forms, were brought in to serve as backdrops for theatrical staging and to punctuate the flatness of planting beds. No plant group was more subject to manipulation than the pelargoniums (Pelargonium), which are often called (erroneously, British gardeners would say) geraniums in the United States. Native to South Africa, pelargoniums are still ubiquitous garden plants: drought resistant, blooming throughout the summer, a plant that has become a symbol of cheerful welcome in window boxes and entry planters. Zonal pelargoniums, introduced in the late eighteenth century, are characterized by alternating bands of dark and light green on their leaves and large, brilliantly colored flower heads. Continual experimentation with hybridizing various Pelargonium species resulted in hundreds of upright, prostrate, variegated, and ivy-leafed cultivars. Instantly recognizable by the general public, the pelargonium is still among the most popular bedding plants in municipal parks.

Growing and Designing With Bedding Plants

By the mid-nineteenth century, glass houses, once a luxury of estate gardens, became accessible to municipalities and commercial nurseries. In Great Britain, the repeal of the glass tax in 1845 dropped the cost of the material and fueled experiments with mass production. In both the United States and Great Britain advances in cast and wrought iron construction developed for the glass pavilions of the Crystal Palaces in London, Syndenham, and New York City were adapted to smaller glass structures. Magazines for gardeners offered advice on ventilation, humidity control, and heating alternatives. Commercial nurseries created acres of glass houses for the mass production of bedding plants. Nurseryman and author Peter Henderson (1822–1890) started with a small shop in New York City selling seeds. By the 1850s, his business skills and ability to predict the horticultural market allowed him to build extensive greenhouses near Jersey City, New Jersey. By his books, aimed at both the professional gardener and the amateur, and by his color catalogs, he developed a market for bedding plants, including his own introductions, most notably zinnias from Mexico and his hybrid ‘Giant Butterfly’ pansy. Henderson visited England in 1885 and noted that the carpet style beds “were interesting to the people in a way that no mixed border could ever be.” He also noted the conspicuous lack of ornament in Central Park and Prospect Park, an omission he attributed to “a lack of taste in the management of our public parks.”

Color theory, the investigation of human color perception, guided gardeners in the design of beds and created the distinctive intense impact of color combinations, either gaudy or brilliant according to your taste. One of the first explorations of color perception was a 1743 treatise by the French naturalist, Georges-Louis Buffon, followed by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Theory of Colours published in English in 1840. But it was the work of Michel Eugene Chevreul (1786–1889), a French chemist employed by the Gobelins Tapestry Works whose work on color, first directed to the textile industry but also to horticulturists, gardeners, and artists, that proved the most influential. His book, The Principles of Harmony and Contrast of Colours and Their Applications to the Arts, published in English in 1854, enhanced the gardener’s understanding of how colors are modified when placed next to each other, in contrast to how the color is perceived when observed alone. Chevreul’s Color Circle, a circular chart organizing complimentary colors opposite each other, was a reference guide for gardeners well into the twentieth century.

Bedding Out in City Parks

The city of Chicago engaged some of the best landscape architects in the country to transform the flat terrain of the city into a sophisticated park system to rival those of Eastern cities. Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, H. W. S. Cleveland, and later Jens Jensen, with his passionate commitment to the prairie landscape, all left their imprint on the city. But parallel to their planning work, the city encouraged ornamental planting in the form of elaborate bedding out schemes. In the 1890s Chicago built a large glass conservatory in Lincoln Park for the display of tropical plants, with extensive plant propagation areas for bedding plants. Earlier Chicago’s South Park Commissioners supported ornamental plant attractions in Washington Park that included a twenty-foot-diameter globe, a sundial of echeverias, and wire structures covered in flowering plants depicting President Grant and Uncle Sam—what one writer called “floral masterpieces.” In 1872 a Board of Botanical Directors was formed under the direction of H. H. Babcock, a prominent botanist and member of the Chicago Academy of Science. In a move antithetical to Olmsted, Cleveland, and Jensen’s native plant perspective, the Board sent requests to botanical gardens and noted horticulturists all over the world and received seeds and bulbs from the United States, Europe, India, and Australia. Many were eventually planted out in the Chicago parks. In 1891, the journalist Charles Pullen wrote extensively on the development of Chicago’s park and parkway system, especially of Olmsted’s plans. He carefully threaded his way through the controversies of natural and artificial but commented that “it is hoped that with the gradual evolution of the grander and simpler elements of the park landscape these features of curiosity will be given to more appropriate places, less antagonistic to the pleasures obtained from natural scenery.”

Citation: Andersen, Phyllis. 2017. Floral Clocks, Carpet Beds, and the Ornamentation of Public Parks. Arnoldia, 75(1): 26–35.

Boston’s Public Garden, still admired for its commitment to the bedding out tradition, rests on a set of artificial conditions that eliminated any call for a rural landscape model. The Garden was created out of brackish tidal flats as part of the landfill project that created Boston’s Back Bay. The supporters of the Public Garden were men with strong horticultural interests as well as a dedication to civic improvement. William Doogue, the Irish-born horticulturist hired to bring architect George Meacham’s original 1859 plan for the Public Garden to life, developed flower adornments for the Garden of great public appeal. He maintained a municipal greenhouse that produced thousands of plants for the extensive beds he created throughout the Garden. A newspaper article in 1888 described the summer scene: acanthus, pyrethrum, beds of silverleaf geraniums and pansies, edged with lobelias and alternanthera. In the midst of this blaze of color, Doogue created a cactus bed, an exotic sight to Garden visitors. In one of the more memorable horticultural disputes of the nineteenth century, played out in the pages of Garden and Forest magazine in the 1880s, Mr. Doogue’s plantings and their accompanying popularity with the public were condemned by both signed and unsigned articles in the publication. Doogue and the supporters of his distinctive floral displays were pitted against an impenetrable fortress of opposition from the likes of landscape writer and architectural critic Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer, Arnold Arboretum director Charles Sprague Sargent, and Frederick Law Olmsted. Doogue scoffed at their limited views, their isolated lives, and, most importantly, their lack of empathy for the taste of the general public.

The bedding out tradition is seen as a historical remnant of the Victorian era, outside the canon of landscape design history: at best, charming and whimsical, at worst an affront to good taste and the sanctity of a natural landscape. It is seen as a vernacular tradition perpetuated by gardeners rather than professional landscape designers or landscape architects. In a postscript to the bedding out tradition, the Philadelphia Museum of Art sponsored an art installation in 2012 by the minimalist artist Sol LeWitt (1928–2007). The work was based on a proposal LeWitt made to the Fairmount Park Art Association in 1981. The resurrected Lines in Four Directions in Flowers was created from LeWitt’s initial instructions: “To plant flowers of four different colors (white, yellow, red, and blue) in four equal rectangular areas, in rows of four directions (vertical, horizontal, diagonal right and left) framed by evergreen hedges of about 2-foot height … The type of plant, height, distance apart, and planting details would be under the direction of a botanist and the maintenance by a gardener.” It was a short term work, installed in 2012 and dismantled in 2015. It, perhaps unintentionally, reiterated the original power of bedding out: the appeal of geometric forms, the intervention of blocks of color in a green field, the fascination with observable change.

Today, we still identify public parks with the core of civic life. The binary of ornamental versus pastoral is still rightfully argued, but, more challenging, is the question: How do you translate planting techniques of mass appeal with contemporary values of sustainability and the still unspoken ideas of taste? In 1856, horticulturist and landscape designer Andrew Jackson Downing argued that the public park could modify artificial barriers of class, wealth, and fashion—a notion that is still valid and still contentious. Sophisticated observers may still feel a degree of discomfort at the use of bedding plants to spell out town names, patriotic emblems, comic characters—the definition of kitsch being “the adaptation of one medium to another.” But in the words of the art historian Tomas Kulka, “If works of art were judged democratically—that is, according to how many people like them—kitsch would easily defeat all of its competitors.”

Further Reading

Bluestone, D. 1991. Constructing Chicago. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Chevreul, M. R. 1987. The Principles of Harmony and Contrast of Colors and Their Applications to the Arts. Revised edition with introduction and commentary by F. Birren. West Chester, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing.

Elliott, B. 1986. Victorian Gardens. London: Batsford.

Musgrave, T. 2007. The Head Gardeners: Forgotten Heroes of Horticulture. London: Aurum Press.

Wilkinson, A. 2007. The Passion for Pelargoniums: How They Found Their Place in the Garden. Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing.

Phyllis Andersen is a landscape historian and former director of the Institute for Cultural Landscape Studies of the Arnold Arboretum.

From “free” to “friend”…

Established in 1911 as the Bulletin of Popular Information, Arnoldia has long been a definitive forum for conversations about temperate woody plants and their landscapes. In 2022, we rolled out a new vision for the magazine as a vigorous forum for tales of plant exploration, behind-the-scenes glimpses of botanical research, and deep dives into the history of gardens, landscapes, and science. The new Arnoldia includes poetry, visual art, and literary essays, following the human imagination wherever it entangles with trees.

It takes resources to gather and nurture these new voices, and we depend on the support of our member-subscribers to make it possible. But membership means more: by becoming a member of the Arnold Arboretum, you help to keep our collection vibrant and our research and educational mission active. Through the pages of Arnoldia, you can take part in the life of this free-to-all landscape whether you live next door or an ocean away.