Near the Arnold Arboretum’s Bradley Rosaceous Collection, at the south end of Meadow Road, lie three ponds whose names commemorate three staff members from the early years of the Arboretum: Jackson Dawson (propagator and superintendent), Alfred Rehder (taxonomist), and Charles Faxon (assistant director and botanical illustrator). These men, along with founding director Charles Sprague Sargent and explorer-botanist Ernest Henry Wilson, played central roles in shaping the Arboretum into the renowned institution that it remains today. Faxon’s mark—in indelible ink no less—is the one we celebrate here.

Charles Edward Faxon was born in the Jamaica Plain section of Boston, Massachusetts, in 1846, not far from the land that was to become the Arnold Arboretum in 1872. As a child, he developed dual interests in natural history and art. Much of his schooling in natural history was provided by his older brother Edwin Faxon (1823–1898), who was an accomplished naturalist and had a particular interest in the cryptogams of New England. After their father’s death in 1855, Edwin took Charles and younger brother Walter under his wing, teaching them the flora and fauna of the countryside surrounding Boston. Edwin had collected an extensive herbarium, which his younger brothers no doubt also used for their studies. Around the same time, English artist James D. Harding published Lessons on Trees, a manual that Charles studied to learn the basics of illustration. As a teenager, he was apparently known to proficiently reproduce Audubon’s illustrations of birds and make successful pencil sketches and watercolors of the New England landscape.

A love of nature might lead to a happy avocation, but as a career, even now it doesn’t always pay the bills. And so, following his public school education, Charles enrolled in the Lawrence Scientific School (now the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences at Harvard University), graduating in 1867 with a degree in civil engineering. He then took up work clerking in the family business of leather procurement and merchandizing. Charles Faxon remained a lifelong learner and studied the classics of English literature as well as teaching himself most of the modern European languages.

In the late 1870s, a pivotal event for the Faxon brothers occurred when Yale Professor Daniel Cady Eaton called upon them to make collections for Eaton’s two-volume Ferns of North America (published in 1879 and 1880). It was in this work that Charles’s illustrations, executed in watercolors, first appeared in print, wonderfully complementing Eaton’s erudite text. Charles was responsible for a number of the plates in Volume One and all of the plates in Volume Two

Faxon at the Arboretum

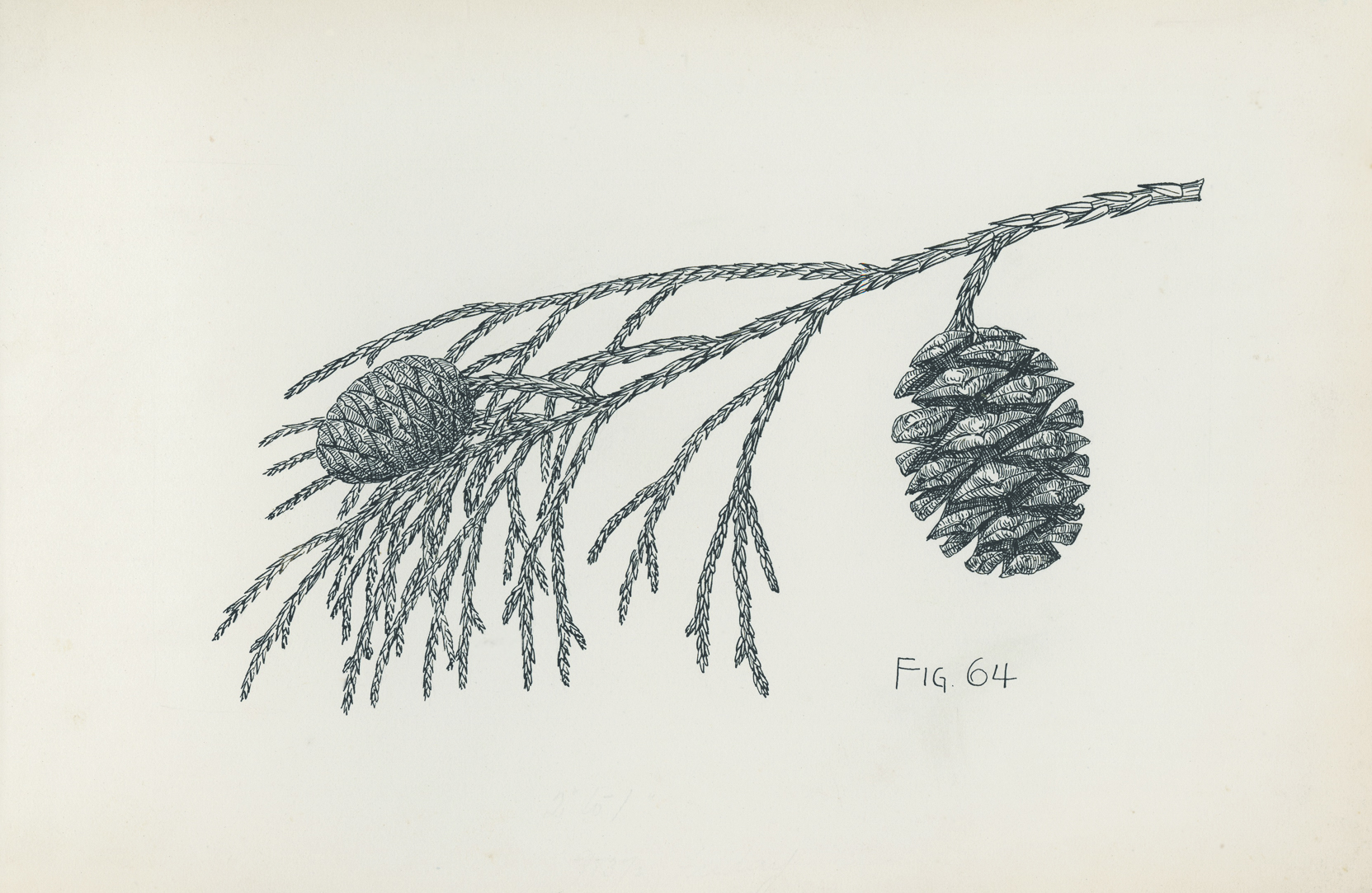

In 1879, Faxon became a botany instructor at Harvard’s Bussey Institution, a school adjacent to the Arboretum that was dedicated to the agricultural and natural sciences. In 1882, C. S. Sargent hired him on a part-time basis as an assistant director at the Arboretum. In this position he was to curate the herbarium and organize the library, both of which were growing as quickly as the living collections. However, Faxon’s primary charge was to assist Sargent with the Silva of North America by producing its illustrations. This seminal treatment, written by Sargent, spanned 14 volumes published between 1891 and 1902, and covered the known woody plants of the United States and Canada. Sargent— the then “dean of American dendrology”—wrote eloquently and assertively about the various ligneous species, while Faxon brought the plants to life with painstaking detail and beauty in pen-andink. By the end of the project, some 744 plates for the Silva had been produced from Faxon’s ink drawings.

One fine example is his illustration of the vine maple (Acer circinatum), native to the Pacific Northwest. Faxon captured the full array of diagnostic characteristics necessary for identification, without whimsy, yet with an astonishing delicacy and grace. In the forefront, the eyes are drawn to a rounded leaf, the margins and primary veins boldly and prominently outlined, as are the striking fruits from the same plane. The remaining leaf of this branch, and those shown on the flowering and sterile branches in the background, are drawn in lighter weights. When coupled to his subtle use of shading, the variable line weights effectively create a depth of field, a sense of realism that does not detract from the scientific purpose. Magnified details of individual flowers, both male and female, as well as fruits, accompany the leaves. Faxon’s drawings were created first as botanical tools: that they are beautiful works of art is a bonus. His training as an engineer, where the rules of technical drawing and drafting were crucial, certainly was put to great use as a botanical illustrator, but he also possessed an artist’s eye for composition, which served to raise his work beyond that of his peers.

Perhaps no finer praise exists than that provided by naturalist John Muir, who reviewed the Silva in the July 1903 issue of The Atlantic Monthly. He wrote, “At the first glance through the book, everyone must admire the fullness and beauty of the plates. They were made in Paris, from drawings from life, by Faxon, the foremost botanical artist in America … these are so tellingly drawn and arranged, [that] any one with the slightest smattering of botany is enabled to identify each tree, even without referring to the text.” While the text was important, the volumes would have been far less successful without Faxon’s illustrations. Professor John George Jack, a friendly colleague of Faxon’s at the Arboretum, felt similarly. Writing in an unpublished reflection (Archives of the Arnold Arboretum), Jack notes that without Faxon, the Silva “would never have grown to its final importance.” And, interestingly, he observed that while Sargent “possessed financial means, a strong will and a liking for gardening and trees …, he was a poor observer of details in nature, a deficiency which was abundantly supplied by Mr. Faxon.” It may well be that it was through Faxon’s ability to recreate natural phenomena that Sargent was able to truly grasp the plants he was charged with describing.

In addition to his work on the Silva, Faxon also produced illustrations for other Sargent publications including the journal Garden and Forest (285 Faxon drawings appeared in the ten volumes published from 1888 to 1897), Forest Flora of Japan (1894), and the Manual of the Trees and Shrubs of North America (1905), which contained 642 Faxon drawings. He also created illustrations for other authors and, according to Sargent, some of the best examples of his work were the 34 drawings that accompanied John Donnell Smith’s descriptions of Guatemalan plants, published in the Botanical Gazette from 1888 to 1894. All told, nearly 2,000 of Faxon’s illustrations were published over a 34-year period, an impressive record!

Beyond his accomplishments as an illustrator, Faxon served dutifully and steadfastly in the management of the library and herbarium. In a letter written August 15, 1905, by Faxon to his colleague Alfred Rehder (who was attending the 1905 Botanical Congress in Vienna), we get a wonderful glimpse of Faxon’s pragmatic nature, as well as a sense of humor. On the subject of taxonomy and the subsequent naming of plants (just as much an issue then as it is now), Faxon laments about the proceedings of the botanical congress: “I fear there is still much to be done before nomenclature rests on a permanent basis. At any rate, for the present there will be as much confusion as ever.” He also seems to poke a bit of fun at Sargent’s obsession with hawthorns (and his penchant for assigning names), noting that he (Sargent) “is describing new species of Crataegus as fast as ever, having done some one hundred this summer!”

Interestingly, Faxon chose not to exhibit his botanical expertise by writing papers; his most noteworthy article was not about plants but rather about the birds of the Arnold Arboretum. Sargent and Jack both attested to his exceptional knowledge and suggested that his lack of authorship was due to his great modesty and unselfish nature. In fact, Jack credits Faxon with providing much of his botanical training. Unlike Jack and many other of his Arboretum colleagues, Faxon did not travel the world, instead preferring short trips to the Berkshires in Massachusetts, the Green Mountains of Vermont, or the Mount Washington region of New Hampshire.

Faxon died in 1918, shortly after suffering a fall at home. In a tribute written in Rhodora that same year, Sargent (not usually one to lavish much praise) writes that “Faxon united accuracy with graceful composition and softness of outline. He worked with a sure hand and a great rapidity, and few botanical draftsmen have produced more. Certainly none of them have drawn the flowers, fruits and leaves of as many trees. Among the very few who in all time have excelled in the art of botanical draftsmanship Faxon’s position is secure, and his name will live with those of the great masters of his art as long as plants are studied.”

Sidebar | From Rough Sketch to Final Press

The archives of the Arnold Arboretum hold all of Faxon’s original ink drawings for the Silva of North America and the Manual of the Trees and Shrubs of North America, as well as many of his initial pencil sketches. The initial sketches are rather coarse, but served as the base upon which the final product would rest. After his rough sketch—often lacking much detail—was complete, Faxon would flip the paper over and rub the reverse side with pencil. He then placed this, image side up, on the final drawing sheet and transferred the image by drawing over the outlines. The refined final drawing would then be produced in ink.

Sargent chose to have Faxon’s magnificent ink drawings engraved in Paris, a center of that art, by Eugene and Philibert Picart under the supervision of Alfred Riocreux, whom Sargent described as “the most distinguished European botanical artist.” He employed the noted horticulturist and landscape designer Édouard André as his agent in France to oversee the work of the sometimes temperamental engravers.

For further reading:

Sargent, C. S. 1918. Charles Edward Faxon. Rhodora 20: 117–122.

Michael S. Dosmann is Curator of Living Collections and Lisa E. Pearson is Head of Library and Archives at the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University.

Citation: Dosmann, M. S. and Pearson, L. E. 2015. Charles Edward Faxon: Botanical draftsman. Arnoldia, 73(1): 2–10.