I first visited the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Garden, in Seal Harbor, Maine, on vacation with my then-fiancée, now-wife, Carrie, in 1997. We were both young landscape architects practicing at different firms in Raleigh, North Carolina. The garden visit had been arranged by Carrie’s college classmate, Sarah Richardson, who lived on Mount Desert Island. After days spent hiking through Acadia National Park’s coniferous forests, granite peaks, and scattered blueberries and junipers, the refined curation of color within the borders of the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Garden was a beautiful and dramatic contrast.

Sarah informed us that the Rockefeller Garden was designed by Beatrix Farrand (June 19, 1872 – February 28, 1959), who also had designed Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, DC. One of Carrie’s classes at Penn State had made a trip to our nation’s capital, where she had been awestruck by the beauty of that garden. The only images I had seen of Dumbarton Oaks came from books and slide lectures, and it would be roughly 18 years before I would encounter Farrand’s work in depth, reading her biography by Judith Tankard, Beatrix Farrand: Private Gardens, Public Landscapes (2009).

Today, through a set of fortunate circumstances, I get to live all year round on Mount Desert Island and have served as CEO since 2015 of the Mount Desert Land & Garden Preserve, which is entrusted with the care of three Farrand-influenced gardens, including the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Garden. In case you have never visited the coast of Maine, I should point out that the indigenous vegetation is not exactly floriferous. Coniferous forest predominates, largely composed of red spruce, black spruce, and white pine. There are some deciduous trees on the edges of the coniferous stands, including alders and moosewood maples. The dominant native ground-floor vegetation is largely composed of rhodoras, sweet ferns, huckleberries, blueberries, and northern bayberries. Underneath this typical plant community on Mount Desert Island are numerous ferns, mosses, lichens, and sedges. This plant community makes for a mix of greys and greens, all in contrast to the pink granite outcrops and glacial erratics that you would frequently encounter. Spectacular in its own right, this landscape inspired the formation of Acadia National Park in 1916.

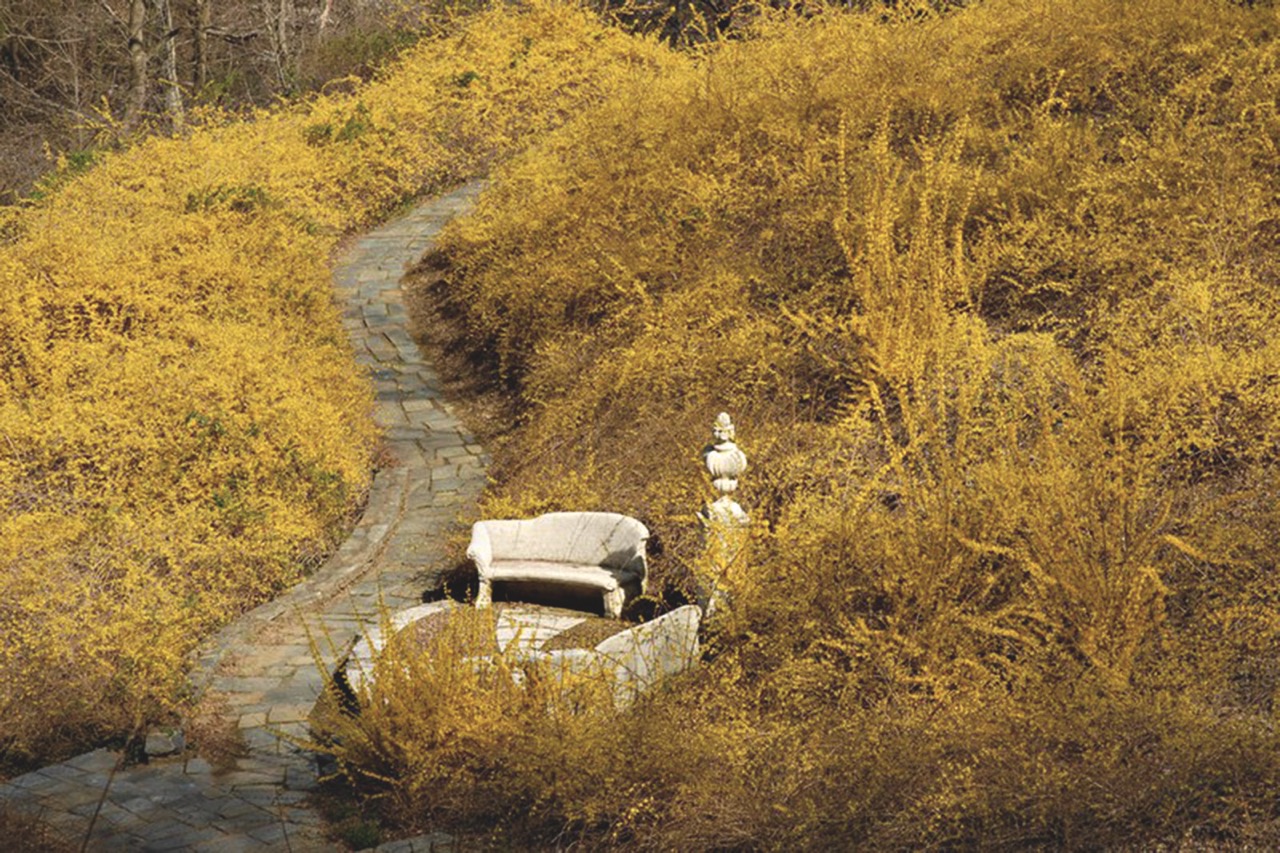

With English-style, mixed-herbaceous borders set off within this landscape, the Rockefeller Garden makes an evocative juxtaposition. Designed by Farrand for Abby Aldrich and John D. Rockefeller Jr. from 1926 through the early 1930s, the garden is a sublime mixture of sophisticated design and a complex palette of plants. I was smitten from the outset with the combination of bold floral colors, statuary sourced from Asia, and Beaux-Arts symmetry, provided most prominently by two parallel axes that run the length of the garden and orchestrate the flow for the visitor. The entry axis, called the Spirit Path, is flanked by carved-stone warriors and priests from eighteenth-century Korea. The second axis, parallel to the Spirit Path, provides the central aspect of the garden and its colorful flower borders with a distant view of a round opening called the “moon gate.” This gate frames the view of a eighteenth-century bronze Buddha in the Shakyamuni, or historical form, from China. As I studied Farrand’s designs in more detail, I would learn how the use of such central orienting axes became a hallmark of her designs.

She left an indelible mark within what is now called Acadia National Park.

Many years after visiting Mount Desert Island and the Rockefeller Garden for the first time, I was fortunate enough to visit Dumbarton Oaks. Like an unfolding, complex novel that you just cannot put down, the garden kept leading from one masterfully designed room to the next, with brilliantly placed plants and sublimely scaled spaces. I distinctly remember encountering the camouflage-print bark of a superb Chinese quince, Pseudocydonia sinensis, at the end of a pathway. Overwhelmed by the beauty of this gorgeous tree, I walked off the pathway and gave it a hug.

What is now the Land & Garden Preserve, was conceived in 1970 as a way for Peggy and David Rockefeller to perpetuate the beauty of the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Garden. They co-inherited the garden with David’s older brother, Nelson, after David’s father, John D. Rockefeller Jr., passed away in 1960. Soon after Peggy and David formed the Preserve as a non-profit, then known as the “Island Foundation,” they were asked to manage the nearby Asticou Azalea Garden. Asticou, or the Azalea Garden as it is known locally, had been built beginning in 1956 by Charles K. Savage, using mature plantings from Reef Point, Beatrix Farrand’s Bar Harbor estate.

Another local garden, Thuya, joined the Preserve in 2000, after its trustees decided that the future of the garden would be in good hands with the growing organization. Thuya’s origins date to 1912, when a Boston landscape architect and Northeast Harbor summer resident, Joseph Curtis, constructed his “rusticator” lodge in Northeast Harbor, naming it for a prominent stand of eastern white cedar, Thuja occidentalis, growing nearby. Charles K. Savage became the trustee of Thuya after Curtis’ death in 1929. In 1956, Savage began establishing gardens at both Thuya as well as Asticou, a story for which more detail will be provided below.

To celebrate his 100th birthday in 2015, David Rockefeller gifted the Preserve over 1,000 acres of land around Little Long Pond, including over 10 miles of carriage roads and 10 miles of hiking trails. This parcel, too, carried Farrand’s legacy: When John D. Rockefeller Jr. was constructing the carriage road system from 1913 until 1940 on what is now both the Preserve and Acadia National Park, Farrand had provided pro-bono consulting on road layout and planting designs. When David Rockefeller passed away in 2017, the Farrand-designed Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Garden joined his gift to the Preserve. Beyond the beauty of the Rockefeller estate in Seal Harbor, Maine, she left an indelible mark within what is now Acadia National Park and the Preserve.

Her ties to the place were deep. When Farrand was 10 years old, in 1882, her parents bought an ocean-front property called Reef Point in Bar Harbor, facing Frenchman Bay. Her childhood at Reef Point fostered a love of plants and landscapes, and for amusement she dug and transplanted native vegetation from the surrounding forests and combined these with cultivated ornamentals. Farrand’s ethos of protecting the natural environment while cultivating intensive gardening spots of horticultural pleasure carries on today at the Preserve with over 1,200 acres of conserved, natural lands connecting our three ornamental gardens.

As her interest in landscape design and planting became more of a passion, she was introduced to Charles Sprague Sargent, the first director of the Arnold Arboretum. Sargent agreed to guide Farrand in her self-education in horticulture and garden design from 1893 to 1894, since at that time, no formal training in landscape architecture existed. While studying at the Arnold, she worked with plants at the Arboretum, as well as at the Sargent family’s estate, Holm Lea, in Brookline, Massachusetts. In addition to learning about the art and science of horticulture from Sargent, she learned to design landscapes to fit a site rather than change a site to fit a design.

From Sargent, she learned to design landscapes to fit a site rather than change a site to fit a design.

The lessons she learned from Sargent carried over as well through the trialing of new plants at Reef Point and elsewhere. From 1946 to 1956, Farrand chronicled the evolution of her Bar Harbor garden along with the noteworthy characteristics of many plants in the “Reef Point Gardens Bulletin.” Farrand found the climate of Mount Desert Island to be particularly hospitable to climbing vines and in the June 1954 bulletin, she describes some of her favorites. Among her descriptions of Aristolochia spp., Ampelopsis brevipedunculata, Vitis spp., and Lonicera spp., Farrand is particularly hopeful and enamored by a vine that “Professor Sargent had scornfully described as a “dud.” This Arnold Arboretum cast-off was Tripterygium regelii. I admittedly had never heard of this Celastraceae member until this mention in the Reef Point Bulletin.

What began as a joint venture with her husband, Max, Farrand continued to develop, seeking to make Reef Point a public teaching garden after his passing in 1945. Max had been the first director of the Huntington Library and Gardens in San Marino, California. The Farrands divided their time between San Marino and Bar Harbor, with a dream of eventually making Reef Point a garden where aspiring horticulturists and garden designers could learn. In October 1947, two years after Max’s passing, a massive wildfire burned almost a third of Mount Desert Island, including many grand, oceanside estates. These massive estates had provided the town with substantial tax revenues, now lost to fire. I mention this because Farrand had sought tax exemption of Reef Point as a public garden, and after these fires (which left Reef Point unscathed), the town had to increase tax assessments. With the burden required to keep her gardens afloat, Ms. Farrand ultimately decided to dissolve Reef Point as a lasting garden in 1955.

Beatrix Farrand’s article on “The Azalea Border” in the April 15, 1949 edition of Arnoldia described the addition of azaleas and other acid-loving plants along Meadow Road by the Arnold Arboretum. Some of the azaleas mentioned in the article included: Rhododendron mucronulatum, R. dauricum, R. canadense, R. vaseyi, R. schlippenbachii, R. arborescens, R. viscosum, R. nudiflorum, R. roseum, and R. calendulaceum. After reading this article from 1949, I began to wonder if Farrand’s interest in azaleas was in any way linked between her desire to see what would grow both in Jamaica Plain as well as at her Bar Harbor estate. As I will describe later, many of her plants were subsequently moved from Reef Point to the Asticou Azalea Garden and Thuya Garden by Charles K. Savage. Asticou Azalea has a substantial collection of azaleas, many of them species grown in the Arnold’s Azalea Border. Farrand, along with her plant recorder, Marion Ida Spaulding, kept an herbarium of the Reef Point plants. Once Farrand decided to no longer keep Reef Point Gardens going, she sent their plant vouchers to the University of California, Berkeley’s herbarium, where I have found 51 vouchers attributed to Reef Point.

In 1956, Farrand sold Reef Point to a Maine colleague, Reef Point board member and architect, Robert Patterson, who sold most of the plant collection to Northeast Harbor hotelier and fellow Reef Point board member Charles K. Savage. Lacking the $5,000 needed to purchase and move the collection, Savage was able to convince John D. Rockefeller Jr. to become a financial backer (that $5,000 in 1956 would be worth over $51,000 in 2022). Rockefeller and his wife, Abby, had worked with Farrand for over a decade on the design and construction of their Maine garden, what is now known as the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Garden. Documents in the Rockefeller family archives show that many of the drawings for the garden and planting designs were by Farrand. After a trip to China in 1921, Abby Rockefeller became enamored with the pink stucco wall around the Forbidden City in what is now Beijing. It served as the inspiration for the wall that surrounds the Abby Garden in Maine.

Outside of her formal garden designs, Farrand often acted as a consultant to Rockefeller about aesthetic decisions regarding the carriage roads both during and after construction. In correspondence in the Rockefeller Archives Center in Pocantico, New York, Farrand commented that the engineers and tradesmen that Rockefeller had hired to landscape the carriage roads of Acadia National Park were lining trees up like soldiers. She urged Rockefeller toward a more natural arrangement, mixing conifers and deciduous trees of different species and sizes.

Farrand understood that the natural character of the carriage roads through the park required a more relaxed style than was evident in her notable formal garden designs. In other writings and sketches to Rockefeller, Farrand suggested covering many of the stone bridges with vines such as Parthenocissus quinquefolia (Virginia creeper). In Acadia National Park today, you will find 16 stone bridges built by Rockefeller, none of them covered with vines. Last year I was hiking along Stanley Brook on the southeastern side of Acadia National Park, and I stopped to admire the Stanley Brook Bridge. I noticed that at both ends of the bridge, equally spaced, was a pair of sugar maples. Growing four sugar maples so symmetrically, on both sides of the bridge, would have been a profound work of art for Mother Nature, so I am going to put this down to Farrand—at the very least, a reflection of her influence and love of symmetry.

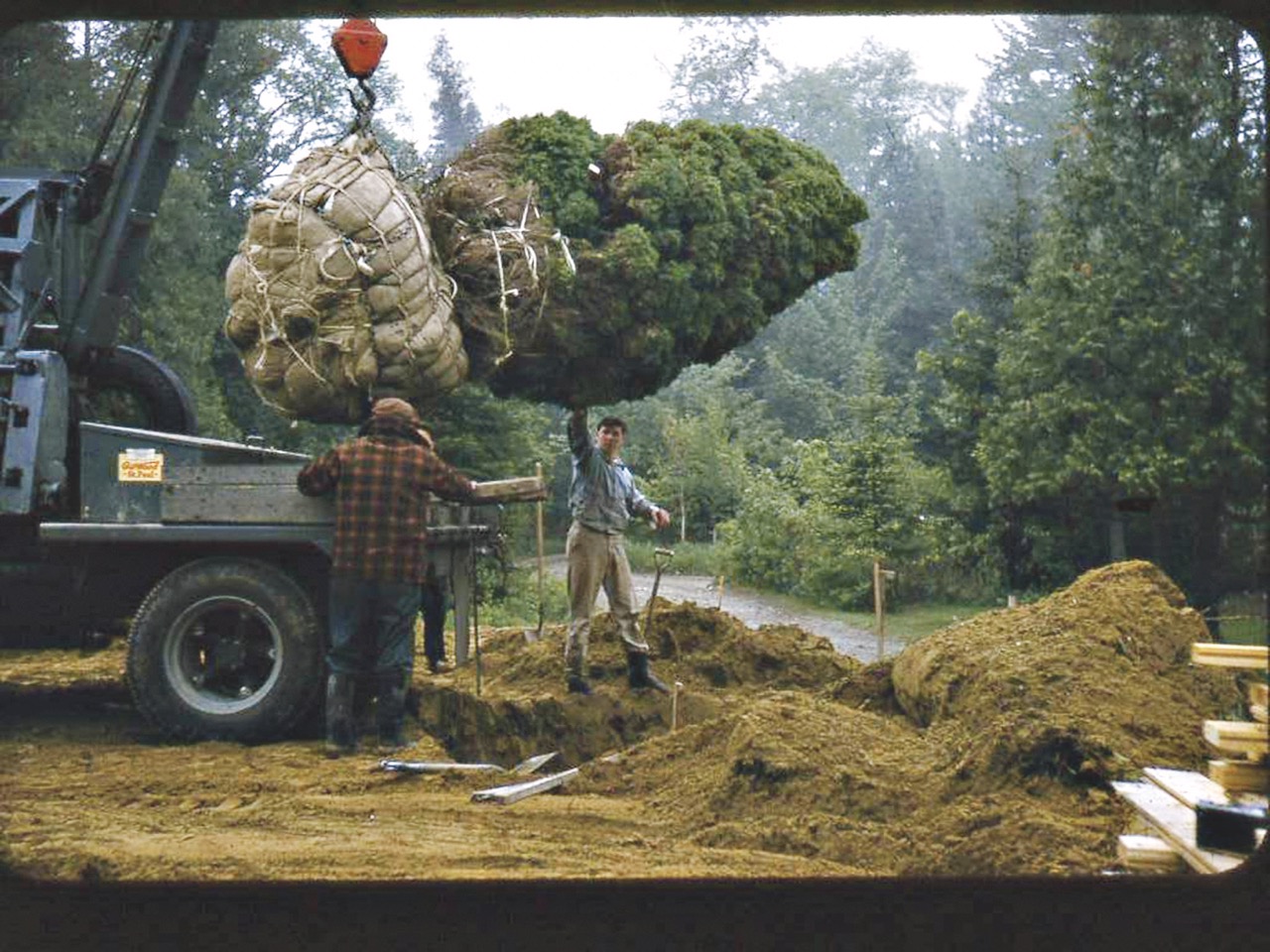

Once Charles K. Savage, or “C. K.” as he was known locally, was able to secure the $5,000 from John D. Rockefeller Jr. for moving the plants from Reef Point to Asticou Azalea and Thuya, he had to act quickly. Savage wrote a narrative to Rockefeller, describing the need for funding and urgency in the matter. The new owner of Reef Point, Robert Patterson, was now responsible for paying taxes on the property and wanted Savage to move the plants before the property would be sold again. The move was done quickly, and records for which and how many plants were relocated remain elusive. White & Franke Tree Service, of Brookline, Massachusetts, with the assistance of various local helpers including Savage’s young daughter and son, moved as many plants as possible the 11 miles from Reef Point to Thuya in Northeast Harbor. The Preserve has several historical photos of these plant moves; we thus know that White & Franke assisted with the move, as their company name is on the door of the moving truck. These photographs show that the largest plants were hand-dug, balled and burlapped with drum-laced jute, and moved with what looked like a converted tow truck, the lift on the back of which acted like a small, mobile crane. The plants were healed in and surrounded by mulch at Thuya during the winter of 1956, while construction continued at Asticou with the hauling in of truckloads of soil and stones that would eventually form the framework for the garden. Construction continued at Asticou and plants were moved from their temporary locations at Thuya until the garden was completed in 1958. Savage had also selected plants from the Reef Point collection for Thuya, planted after the Asticou plantings were completed.

I hoped there was a document to be uncovered in someone’s basement, outlining all the plants purchased, moved, and planted by Savage. During research for this article I learned that even Farrand was unsure of what existed at Reef Point. As she was building the collections, she noted her continuous desire to correctly identify the plants in the garden, even bringing William Judd, the Arnold Arboretum’s chief propagator, to Maine for help with inventorying the collection. Whether due to the rapid movement of the plants, the transfer of records and herbarium vouchers from Reef Point to Berkeley per Farrand’s request, or the inadequate identification of the plants by their owner, the Preserve has never had a consolidated record of what was moved from Reef Point to Asticou and Thuya.

A quiet, distinguished vibe seems to emanate from the plants that came from Farrand.

The current manager of Asticou Azalea Garden, Mary Roper, has worked to identify the plants under her care for over three decades, including some of the plants moved from Reef Point in 1956. Mary began working at Asticou in 1989, some thirty years after the moves were completed. Over the years, Mary, like Farrand before her, has assessed the nuanced details of flowers, leaves, and stems of the plants under her care to develop a proper identification. Beginning in late 2022, Grace Brown, the Preserve’s plant recorder and lead gardener at Asticou, will begin sharing some of these plant records via our new plant records database, which will be accessible at the Land and Garden Preserve Website.

Despite the remaining mysteries, the spirit of what Beatrix Farrand envisioned at Reef Point lives on today at the Preserve, within the gardens of Asticou, Thuya, and Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, as well as in the forests and meadows of our natural lands. This is felt most powerfully at the Abby Garden, with its overall layout, plantings, and ornamentation preserved since the 1920s. Asticou and Thuya were designs of C. K. Savage, but it was the influence of Farrand’s relocated plants that completed these garden arrangements. When I tell someone who has visited the Preserve that I work there, “I just love (insert either Asticou Azalea, Thuya, or Rockefeller Garden here)!” is usually one of the first things I hear in response. When I ask why they love their garden of choice, the responses often embrace the spirit of these places. I felt that special spirit when I first visited the Abby Garden in 1997, and I still sense this every time I visit. When I walk through Thuya, as I brush up against the old Kalmia latifolia that came from Reef Point, a quiet, distinguished vibe seems to emanate from the plants that came from Farrand. Asticou Azalea’s design and plant masses are calm and subdued, much like I assume Farrand was during her life. Yet during the spring when the azaleas and cherries burst forth with an explosion of blooms, I can see Farrand’s love of beauty in plants and the art of arranging a garden for others to enjoy.

Rodney Eason is CEO of the Land & Garden Preserve, responsible for the care and preservation of the gardens discussed in this essay.