Ernest Henry Wilson (1876-1930) explored the regions Sichuan and Hubei in Western China and borderlands of Tibet four times, in 1899-1902, 1903-1906, 1907-1909, and 1910-1911. The former two trips were executed for the Veitch Nursery Firm in England, the latter for the Arnold Arboretum.

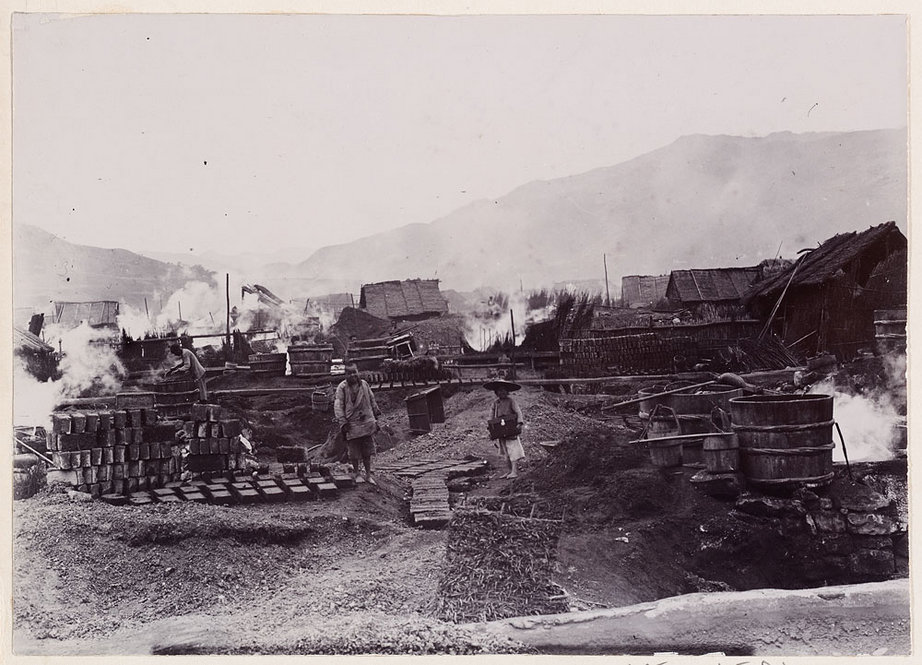

The Arnold Arboretum trips were the more important ones, being scientific and comprehensive in nature, while the Veitch expeditions were commercial in design, yielding very few species and answering fewer scientific inquiries. In 1913, Wilson published A Naturalist in Western China about his Chinese trips for the Arboretum. These two volumes enumerate his significant plant collections, entertain with anecdotes from his fabulous adventures and educate about the complex and rapidly changing culture of early twentieth century China. The beauty of these books is present because they don’t strictly adhere to the scientific method, yet neither do they provide farcical or strained vignettes. Instead, they belong to a fantastic and original “hybrid genre,” combining Wilson’s analytic genius and artistic know-how into a good read for anybody interested in the crossroads of art and science.

Volume I: Travel, Localities, Culture

The first volume is the more general of the two, following Wilson’s itinerary as he travels through the villages, cities, and wildernesses of Western China. He recounts each location visited during his fourth expedition (1910-1911) in chronological order, and makes references to his third expedition (1907-1909) when certain events from it seem to capture his train of thought. The timeline does have a tendency to become confusing, and it is often unclear exactly what happened to Wilson on which trip. But it hardly matters in the conception of the book as a whole: its purpose is not to be precise in every single detail, but only the ones that count, namely, Wilson’s experiences and observations, which he flawlessly imparts to his readers.

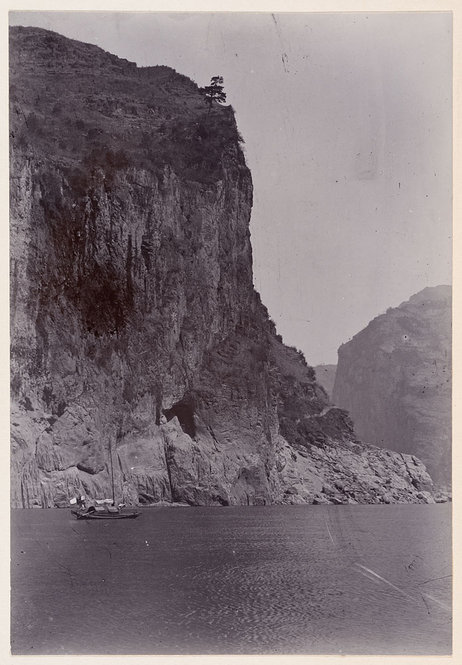

This book, and its sequel, can realistically be called large amalgams of observations. These observations are, however, compiled into large volumes, and woven together seamlessly. One minute, Wilson is crossing rotted bridges, staying in stinking inns and suffering beneath driving rain. The next, he climbs atop a hill, and beholds magnificent sights: “limestone cliffs rear themselves some 2000 feet, abutting on a cultivated slope where Walnut trees are scattered around. Crowning a bluff is a tall tower, and near-by another in ruins, telling of glories now departed.”

Wilson is constantly on the move, and so are his fast paced accounts. Each paragraph yields a new gem. In fact, there are so many fascinating tales to tell that Wilson doesn’t even take the time to elaborate on an injury he suffered in a landslide: “in 1910, when descending the Min Valley, I unfortunately got involved in a minor [landslide], and sustained a compound fracture of the right leg just above the ankle. In many places rockslides are constantly occurring…” In the entirety of the book, no more is heard about the incident. It’s as if Wilson is so enraptured by his passion for exploration and botanic research that he has no time for his own personal injury. He must move on the next analysis and description, and the next, and the next.

While the binding element of Volume I is the description of the expeditions’ itineraries and locales, the other ingredients are primarily botanical, anthropological and political observations. The descriptions of the flora of China are best left to the discerning reader, being better appreciated with a preexisting familiarity with plants. But Wilson doesn’t fail to throw in a few crowd-pleasers, like the “Big Creeper,” an “enormous specimen” of Mucuna sempervirens covering a hillside, with a trunk “almost as thick as a man’s body.” As a scientist, Wilson was most familiar with plants and plant-life. Yet he was a man of learning, and was thought about many fields of study, hence the presence of descriptions framing humanity and analyzing Chinese government and political functions. Wilson didn’t go to China simply to grab plant specimens and get out. He was truly fascinated by China and the Chinese as a whole:

“No country, outside Europe and North America, is of such perennial interest to the world at large as China. Ever-changing yet ever the same, she is the link which connects the twentieth century with the dawn of civilization, epochs before the Christian era. To travel leisurely through this vast country is an education which leaves an indelible impress on all fortunate enough to have had the experience. The Chinese do not see time from the Westerner’s view-point, and for the traveler in the interior parts of China the first, last, and most important thing of all is to ever bear this in mind.”

Be sure to look for the last installation in this two part series, covering Volume II of E. H. Wilson’s A Naturalist in Western China.

—Lucas Galante, Bennington College, Arnold Arboretum Library Intern