Staff from the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University and colleagues from the North America-China Plant Exploration Consortium are embarking this fall on a plant collecting trip in the Appalachian Mountains region, the conservation partnership’s first expedition in North America in its 30-year history. Our intrepid explorers—Head of Horticulture Andrew Gapinski, Propagator Sean Halloran, and Living Collections Fellow Jared Rubinstein—are sharing their experiences in the field through a series of blogposts. This is their fifth transmission; see the first, second, third, fourth, and sixth parts.

We entered the twilight of our 2019 North America-China Plant Exploration Consortium (NACPEC) expedition in North Carolina, at the Southern Highlands Reserve in Lake Toxaway, NC, which focuses on conserving the flora of the Appalachians. We took a tour of their stunning arboretum, which is situated about 4,500 feet above sea level, and then hiked even higher to their natural area for collection.

We were joined in our collection by Lauren Garcia-Chance, Director of Research and Conservation, and Eric Kimbrel, Director of Horticulture, as well as Pepper the dog.

At around 4,800 feet we finally found some oak trees with a good number of acorns. Oaks (Quercus spp.), among other trees and shrubs, do not always produce abundant fruit every year. Instead, they produce large amounts of fruit, in this case acorns, during what are called “mast” years. There are many factors that influence whether a year is a mast year or not, but regardless, it did not seem to be a mast year for oaks in Kentucky and Tennessee and we hadn’t found many acorns.

Fortunately for us, the higher elevations at SHR seemed to have helped the oaks produce more acorns, so we were able to collect from a group of trees we eventually identified as Quercus falcata, or the southern red oak.

In all, we made six collections at SHR and had a wonderful visit with their staff. That evening, we took advantage of the beautiful weather and our AirBnb’s lakeside location to kayak in Lake Cherokee before cleaning seeds and sorting through vouchers.

The next morning we had an open day on our schedule, so we backtracked an hour or two to collect in the Chattahoochee-Oconee National Forest in Georgia. We drove through forest roads and hiked along the Chattooga River Trail to add six more collections. At the Holcomb Creek Falls, we found a beautiful patch of what we thought was white turtlehead, Chelone glabra. Though beautiful, this flower wasn’t on our desiderata (target taxa list), so we just admired it and continued on.

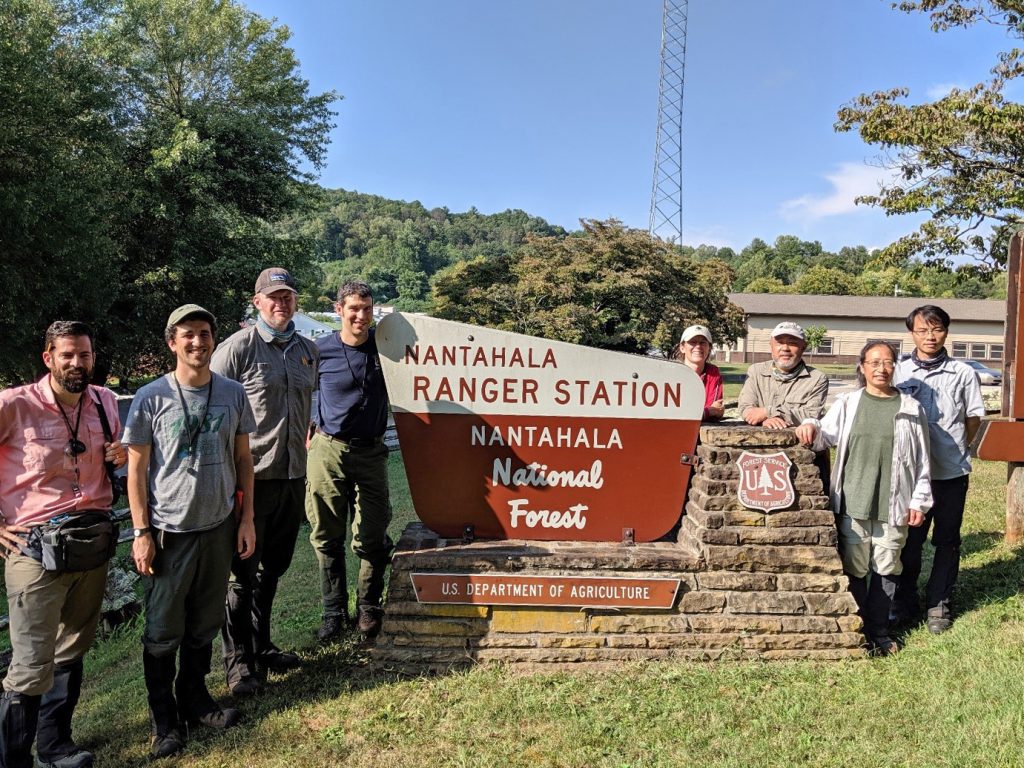

Our next collection day brought us to another National Forest—this time we headed to Nantahala National Forest in North Carolina, accompanied by Forest Botanist Matt Bushman and Lauren Garcia-Chance from the Southern Highlands Reserve.

Matt brought us to a boulder field on a very steep hill up from Jake Branch, a creek in the National Forest, where we found some great examples of yellowwood (Cladastris kentuckea), but none bore fruit.

On the way down to the car, we stumbled upon a not-so-happy rattlesnake (our first of the trip!) whose rattle warned us to give it a wide berth.

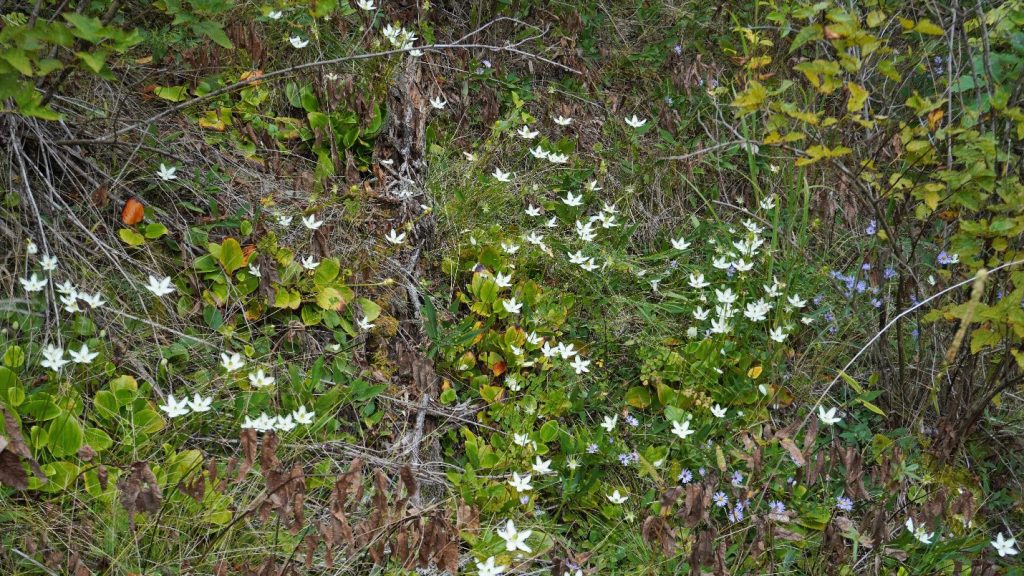

Next, we headed to the Buck Creek Serpentine Barrens, a stunning spot in the national forest where twenty-two of North Carolina’s rare or endangered plants are endemic. Among our favorites were the kidney-leaved grass of Parnassus (Parnassia renifolium) and the fringed gentian (Gentianopsis crinata).

Nantahala was one of the highlights of the trip for us—it had a wonderful diversity of species and truly amazing endemic plants. We made ten more collections, and Matt’s botanical knowledge was completely invaluable.

Finally, our last day of collecting arrived, and we headed into Cherokee National Forest for what we hoped would be a fateful and successful ultimate day. Our primary goal for the day was to find seed of Buckleya distichophylla, a rare, hemiparasitic plant that attaches its roots to those of other plants to gain nutrients. I’d heard some unconfirmed rumors from various botanists in Tennessee that we might find some near Watauga Lake, so we drove that way and started hiking. Buckelya seems to prefer, though doesn’t require, parasitizing the roots of hemlock, so we were pleased to see some Carolina hemlock (Tsuga caroliniana) growing along the shores of the man-made lake. It was devastating, however, to see the damage incurred by the hemlock wooly adelgid and elongate scale, which have been ravaging hemlock populations throughout eastern North America.

Despite the hemlock decline, we ended up discovering a HUGE patch of Buckleya growing among the remaining hemlock, and many of them were in fruit. Though not a terribly impressive looking plant, Buckleya’s hemiparasitic nature and the fact that it is the Arboretum’s oldest collected plant at present made us especially excited to find more.

We also managed to find some roses and dogwoods growing along the shore, helping Xinfen round out her survey of the area’s Rosaceous plants.

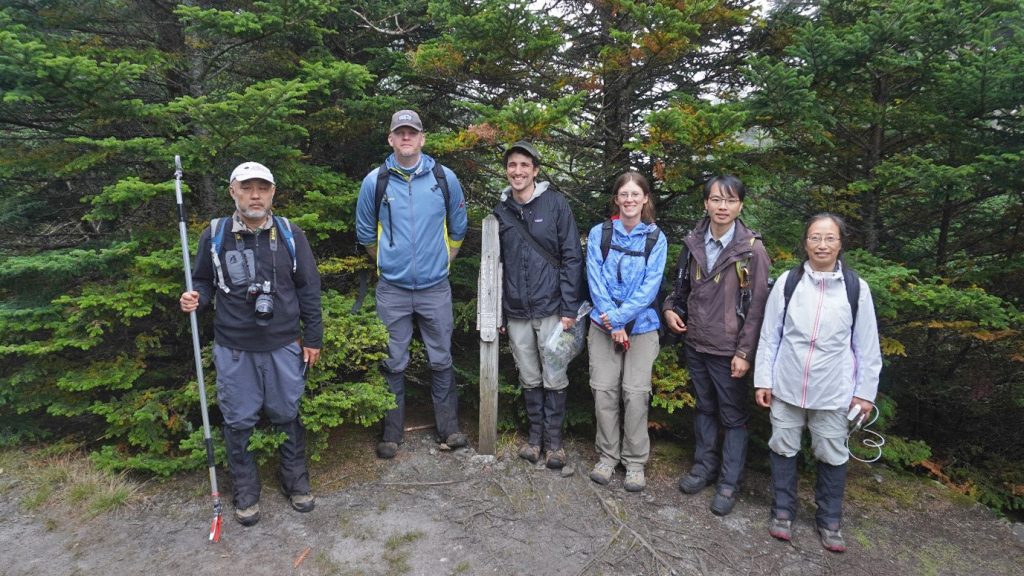

From Lake Watauga we drove up, up, and up to the top of Roan Mountain, where we straddled the North Carolina-Tennessee Border by hiking a stretch of the Appalachian Trail. Along the way, we stumbled upon a familiar name on a historic plaque.

We arrived at a trailhead to the more than 2,000 mile Appalachian Trail, and were quickly shrouded in fog and kept in the dark by a thick canopy of firs and spruces.

While hiking the trail, we made our final collections of dogwood, mountain ash, and alder. We finally had a chance to use our drop cloth for the dogwood, which we shook to make the delicate fruits fall in a more controlled manner. Afterwards, we could pick up the seeds from the cloth.

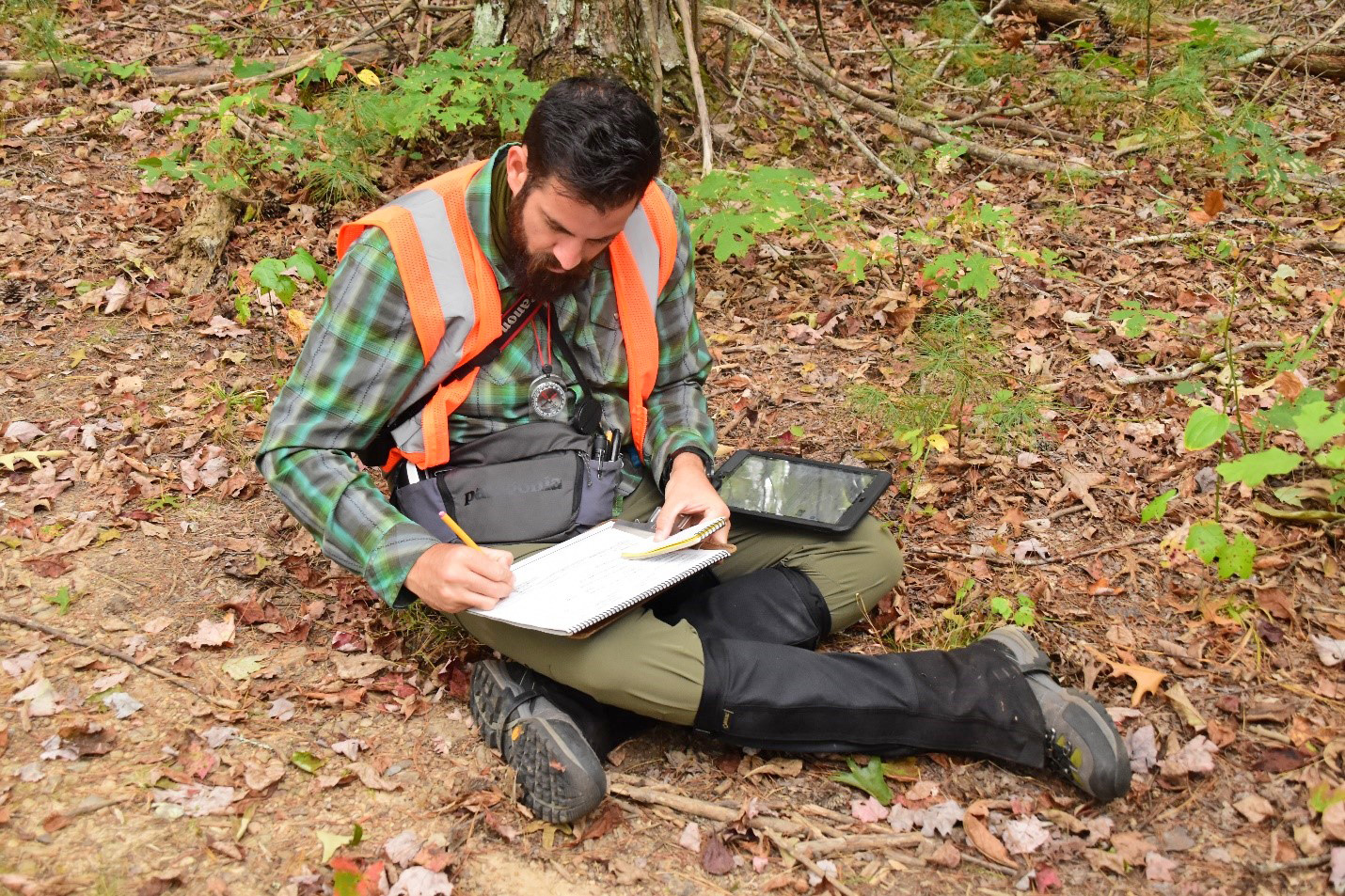

In addition to collecting seeds and herbarium vouchers, one of the most important aspects of our collection trip was note taking. For most of the trip, Sean was in charge of recording all kinds of data about each collection, including a plant’s coordinates, the other associated plant species, the number of plants we collected from, and other descriptive information about the plant and site.

These data will be invaluable when we get back to the Arboretum and begin sorting and accessioning our collections into our database.

We ended our last day of collecting with a beautiful Alnus viridis, the green alder, which only grows in the Southeast atop Roan Mountain. It was collection number 99, but due to a record keeping error, we had actually made a total of 100 collections throughout our several weeks of collection.

Our days of collections were over, but the trip was not yet complete. After one more night’s sleep in North Carolina, we drove north to Washington, DC for the final leg of our trip.

Read the next story in this series of blog posts.