Our horticultural reunion with The Dawn Redwood

Introduction

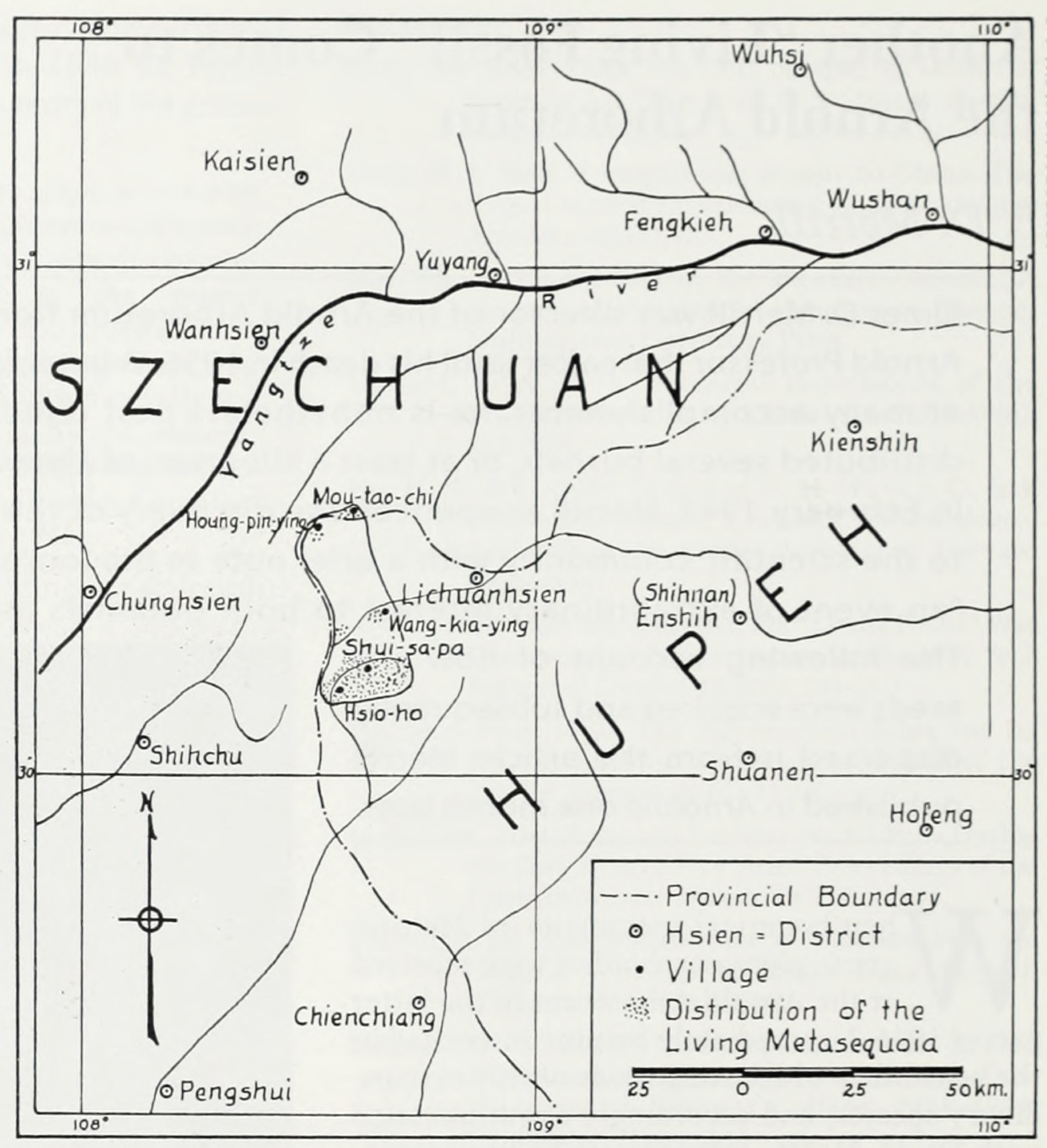

Metasequoia glyptostroboides, popularly known in the west as the Dawn Redwood, had largely been believed to have become extinct millions of years ago. By the end of the 1940s, that was found not to be the case. This is an overview of how Dawn Redwood was rediscovered in China’s Hubei (known then as Sichuan) province, then introduced to temperate areas of the world such as the United States, Europe, and even New Zealand.

I find it a lovely ornamental [tree] well suited to parks, golf courses and other large areas; would make a very effective screen, grouping or for use in lining long drives or streets; where it can be grown without problem or freeze damage it should be given adequate consideration.

— Michael Dirr, Manual of Woody Landscape Plants

A Curious Encounter

In the winter of 1941, while journeying from Hupeh to Szechuan Professor Kan T. (Department of Forestry of the National University) saw on the roadside at Mau-tao-chi in Wan Hsien a large deciduous tree that was called by the natives shui-sa, or water fir. Unfortunately no specimens were collected at that time, as all the leaves had fallen off due to the seasonal cold.

Photograph by Larissa Glasser. Photograph by Larissa Glasser.

Then, in 1942, Professor Kan requested Yang Lung-hsin, principal of the Agricultural High School, to collect herbarium specimens of these shui-sa. Unfortunately, these were not identified.

In the summer of 1944, Wang T. , a staff member of the Central Bureau of Forest Research, went to western Hupeh to explore the forests at Shenlung-chia, and was asked by Mr. Yang to go to western Hupeh by way of Wan Hsien and Enshi in order to investigate the shui-sa at Mou-tao-chi.

At Mou-tao-chi, Wang collected herbarium specimens of leafy branches and fruits of this tree and thought it to be lyptostrobus pensilis Koch, or shui-sung, the water pine, which is a common deciduous coniferous tree in Kwangtung province found also in Kiangsi.

Wu Chung-lung, an assistant in the department of forestry of the National Central University, met Wang who gave him a branchlet of the water fir with two cones. Wu presented these to Cheng W. C. of the same department, who considered this tree not a Glyptostrobus but a new genus, on account of the opposite character of the peltate fruiting scales, which differ from those of Glyptostrobus although the deciduous linear leaves are somewhat similar.

Cheng then sent his assistant, Hsieh C. Y., to go twice to Mou-tao-chi in February and May 1946, and these trips resulted in the collection of specimens of flowers and young fruits of this water fir, from which Cheng understood the morphology of this tree more clearly.

In February of 1946, Cheng Wan-Chun of the National Central University in Nanjin, sent Hseuh Chi-Ju to Lichuan in Hubei to collect specimens of a newly discovered genus temporarily named Chieniodendron sinense. He sent these to botanical institutions in China, Ireland, and the United States for additional evaluation and study.

Elmer Drew Merrill, then director of the Arnold Arboretum, received the specimens and soon contacted Hu Xiansu (Hu Hsen Hsu), then director of the Fan Memorial Institute of Biology, who had received his doctorate from Harvard and the Arboretum in 1925. Hu had collaborated with Cheng to determine and name the newly described species Metasequoia glyptostroboides.

As the local people looked upon the Metasequoia as a sort of divine tree, they built a shrine beside it. Among the villagers there were quite a few traditions about the Metasequoia. As a result, the villagers considered its fruit-bearing condition to be an indication of the yield of crops, and the withering of its twigs or branches a forecast of someone’s death.

— Hsueh Chi-ju. 1991. “Reminiscences of Collecting the Type Specimens of Metasequoia glyptostroboides.” Arnoldia, 51(4): 21.

A Breakthrough

Eager to cultivate the new species, in July of 1947 Merrill sent Hu $250 to fund the collection and shipment of seeds to the Arnold Arboretum.

These and additional funds from Ralph Chaney at the University of California, Berkeley, were forwarded Cheng, who then sent his assistant, Hwa Ching-Tsan, to collect seeds from the population in Lichuan.

In January and again in February of 1948, two seed shipments arrived at the Arnold Arboretum.

After keeping a share of seeds for the Arboretum collections, the germplasm was promptly redistributed in at least 600 packets to other gardens, arboreta, and universities around the world.

It is safe to say that until subsequent collections of dawn redwood in the 1990s, all Metasequoia in the west can be traced to these original 1948 seed lots and their progeny.

The timing of the discovery of the species and this particular contract are incredibly important.

This was to be one of the last collaborations between American and Chinese botanists before the Chinese revolution prohibited access to Westerners until 1980 with the Arnold Arboretum’s Sino-American Botanical Expedition.

It was a close call. Had the discovery of Metasequoia conicided more closely with the revolution of 1949, the species may in fact have been extirpated from the wild without any knowledge and scientific investigation, let alone introduction and now prominence in gardens.

It has been argued in some quarters that we approach the condition of diminishing returns in the botanical exploration of China, a field that has long been one in which the Arnold Arboretum has specialized. This statement is doubtless true to a certain degree, but from what has appeared in extensive collections made within the past three decades, I am of the opinion that a vast amount of fieldwork is still called for and is still justified. This remarkable Metasequoia find bears out this belief.

— Merrill, E. D. 1991. “Metasequoia, another “living fossil.” Arnoldia, 51(4): 16.

A Controversy

Photograph by Larissa Glasser. Photograph by Larissa Glasser.

The plot thickens.

During 1948, an academic storm began to brew between Merrill and Chaney, which continued for a number of years thereafter.

When Chaney and Dr. Milton Silverman (science reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle) made their own March 1948 expedition to China, they published a series of articles about their journey to the valley of the Metasequoia, or “Dawn Redwood,” as it had been christened by Chaney.

These articles, which duly mentioned the Arnold Arboretum’s role in procuring the seed shipment from Cheng, made a great splash in the press which led to Chaney being credited with collecting the seed that made up the 1948 distribution and even to be the tree’s discoverer. Merrill expressed his outrage at Chaney.

News articles along with correspondence between the aggrieved parties and their colleagues can be consulted in the Metasequoia glyptostroboides Records, 1940-2010 (Arnold Arboretum Archives), and Merrill collections at the Archive of the Mertz Library (New York Botanical Garden).

Looking Back

We know that The Arnold Arboretum sent out many hundreds of seeds of the newly rediscovered Metasequoia to institutions and gardens … but how many exactly and to which ones?

We who staff the Archive of the Arnold Arboretum would love to know the answer to that question. During the course of a year, we receive inquiries from researchers and owners of gardens from all over the world who seek to trace the ancestry of their own Metasequoia trees.

We’ve been able to glean some information from our plant distribution archives, but considering the quantity of germplasm that Merrill and Arboretum staff sent out as the 1940s came to a close, we have precious little information to draw from.

We might speculate that hastiness could have been a factor due to the Merrill-Chaney controversy, so thorough record-keeping of Metasequoia distribution may have been a lesser priority at that point in time at The Arnold Arboretum. The seeming rush to get the seeds distributed to other individuals and institutions as expeditiously as possible may have been the main task at hand.

The Dawn Redwood is a highlight of our Living Collections, not only because of its rebound from supposed extinction (indeed it had come alarmingly close), but also due to mysteries yet to be unraveled.

- What, for instance, can Metasequoia tell us about climate change?

- Why did the tree survive in a seeming isolated inland patch of China, rather than in a geographic equivalent in the West?

- What are the sacred beliefs and their origins related to the tree in comparison with its neighboring native forest flora?

- What can we learn about the dispute between Merrill and Chaney, the mystery of the AA-origin seed distributions?

- What does this expedition teach us about documentation and planning for future expeditions?

Dig Deeper

- Arnoldia 58(4) and 59(1), 1998-1999, entire issues devoted to Metasequoia.

- Chaney, Ralph W. “A revision of fossil sequoia and taxodium in western North America based on the recent discovery of Metasequoia.” Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 1950. 40(3): 171-262.

- Dirr, Michael., and Dirr, Bonnie. Manual of Woody Landscape Plants : Their Identification, Ornamental Characteristics, Culture, Propagation and Uses. 6th ed. Champaign, Ill.: Stipes Pub., 2009.

- Hu, H.H. “How Metasequoia, the ‘living fossil’ was discovered in China.” Journal of the New York Botanical Garden. 1948. 49(585): 201-207.

- Hu H.H., Cheng Hsueh Chi-ju. “Reminiscences of collecting the type specimens of Metasequoia glyptostroboides.” Arnoldia 1985. 45(4): 10-18.

- Metasequoia glyptostroboides Records, 1940-2010. Archives of the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University.