Plants collected on this Expedition

| Plant ID | Accession Date | Received As | Origin | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Expedition Stats

North Korea, South Korea, Japan, Taiwan

- Event Type

- Expedition

- Collection Type

- Germplasm, Herbarium Specimens

- Arnold Arboretum Participants

- Ernest H. Wilson

- Other Participants

- Takenoshin Nakai, Ryozo Kanehira

From 1917-1919, Ernest Henry Wilson led an expedition to eastern Asia to collect germplasm germplasm: in the wild and from cultivation. He visited many places in the region including sites in Japan, Taiwan (formerly Formosa), and Korea, bringing back seeds, plant material, and herbarium specimens herbarium specimens: to the Arnold Arboretum. He also took the majority of the photographs which illustrate this story.

National loyalties laid bare by World War I brought tension among the Arboretum staff. Wilson, who was English and quite patriotic, had come into conflict with his Plantae Wilsonianae collaborator Alfred Rehder, who was a native German. By later 1916, Arboretum director Charles Sprague Sargent thought it wise for workplace harmony to dispatch Wilson again to eastern Asia to collect plants.

This expedition, which started as a one-year engagement and expanded to a second year, would be Wilson’s most successful collecting trip. He took to the field exploring many remote locations that he had not been able to visit on his 1914 trip to Japan. His family, wife Ellen, and daughter Muriel, again accompanied him.

1917

The Southern Japanese Islands

Wilson and his family left Boston in at the beginning of 1917, arriving in Japan in February. He soon traveled south to the Ryukyu (Liukiu) Islands, where in his words, “pine and palm meet.” He spent the bulk of his time on Okinawa but made several excursions to surrounding islets to explore the tropical flora. During more than two weeks in the islands he made about 600 herbarium collections representing over 100 species. He also took 60 photographs.

After a short time back in Tokyo, he again returned to the field in March. He explored the Izu Islands (also known as the Ogasawara Islands), a subtropical archipelago due south of Tokyo. On Izu Oshima, among the many plants he saw, Wilson noted a prostrate form of juniper (probably Juniperus taxifolia var. lutchuensis) that he had also observed on the Ryukyu Islands.

A chance conversation with Japanese agricultural officials led to an invitation to visit the Bonin Islands during the latter part of April. The islands, which include the island of Iwo Jima, had been highly deforested and the land used to grow sugarcane. Wilson collected over 600 herbarium specimens and took over 30 photographs during his visit to the botanically unexplored islands.

Korea

“Not much is known here of the flora of Korea, and only a few Korean plants are growing in the Arboretum, but these have proved so successful that it has seemed desirable to undertake a systematic exploration… and of introducing plants into this country from a region with climatic conditions as severe as those of New England.”

Charles Sargent

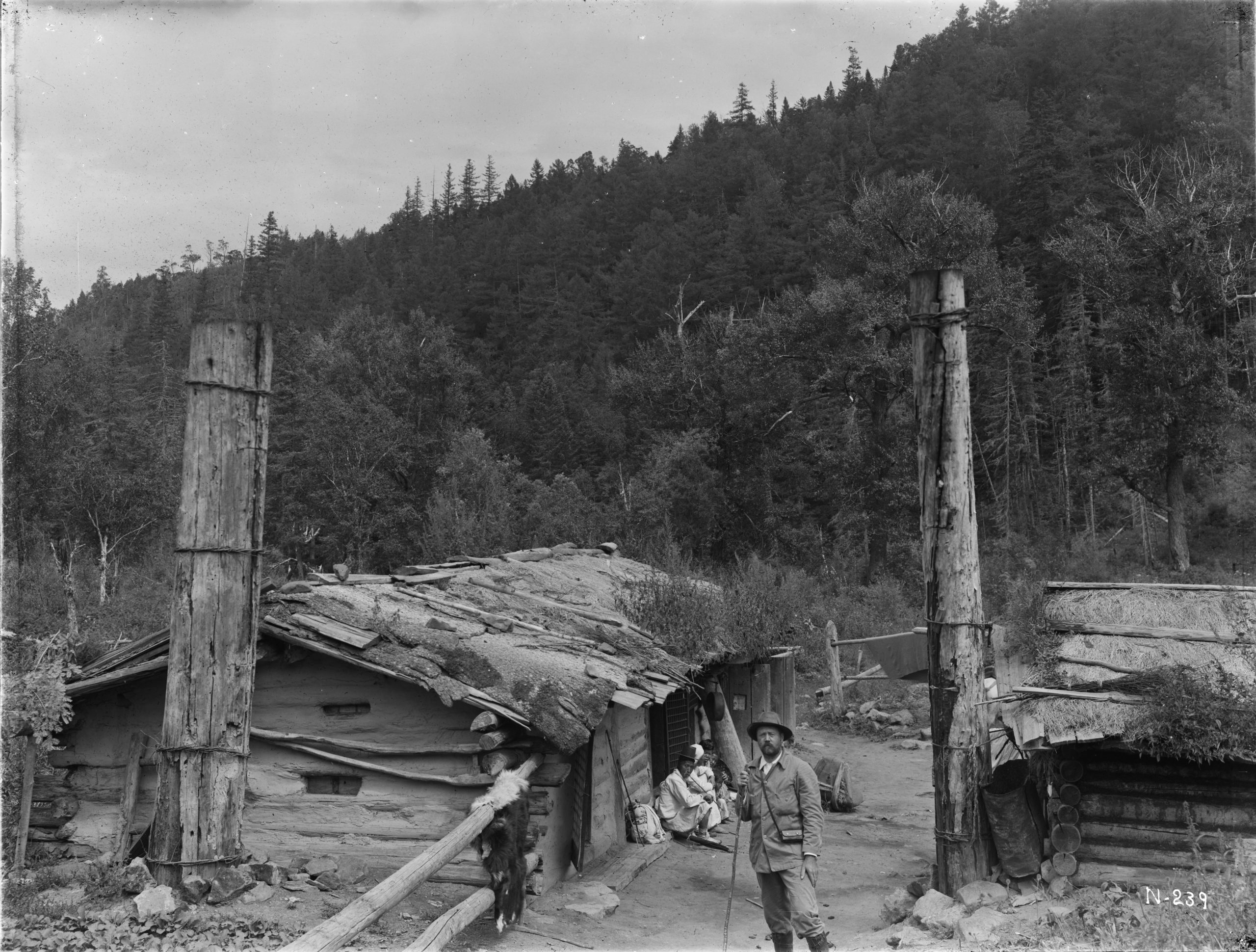

Wilson spent the remainder of the year exploring Korea. The country had been under Japanese occupation since the Russo-Japanese War in 1905 and therefore it was Japanese forestry officials that accompanied him during his explorations. They may be recognized by their western-style uniforms.

Ulleungdo Island

He arrived in late May and soon made his first foray into the field with Japanese botanist Takenoshin Nakai. They traveled to Ulleungdo (Oo-ryong-too) Island in the Sea of Japan, 80 miles (129 kilometers) off the Korean coast. Their goal, in Wilson’s words, was to collect, “where the floras of Japan and Korea meet.” The island, home to over 30 endemic species, probably acted as a refugium refugium: during glaciation on the mainland. Wilson made about 80 collections of herbarium material and live plants, including several that he thought might prove to be new species.

Northwestern Korea

After a return to Seoul to see his family, Wilson was off again in early June to the northwestern part of the country. He explored an area in what is today Pyonganbuk-do, North Korea (North Heian Province, Korea). In the middle of July, he crossed the border into China and traveled as far west as Dalian, Lioaning Province (Dalian and Port Arthur, Manchuria). Returning east back into Korea, he visited Daeyou-dong (Taiyudo) and Bukjin (Pukchin) before returning again to Seoul at the end of the month.

Wilson primarily explored deciduous forests. He comments in a letter to Sargent, “Compared with the rich floras of western China and of Japan that of Korea is markedly less varied. Nevertheless I have seen and collected a number of plants which, heretofore, were mere names to me, and some scarcely that.” He made about 100 herbarium collections and took nearly 50 photographs.

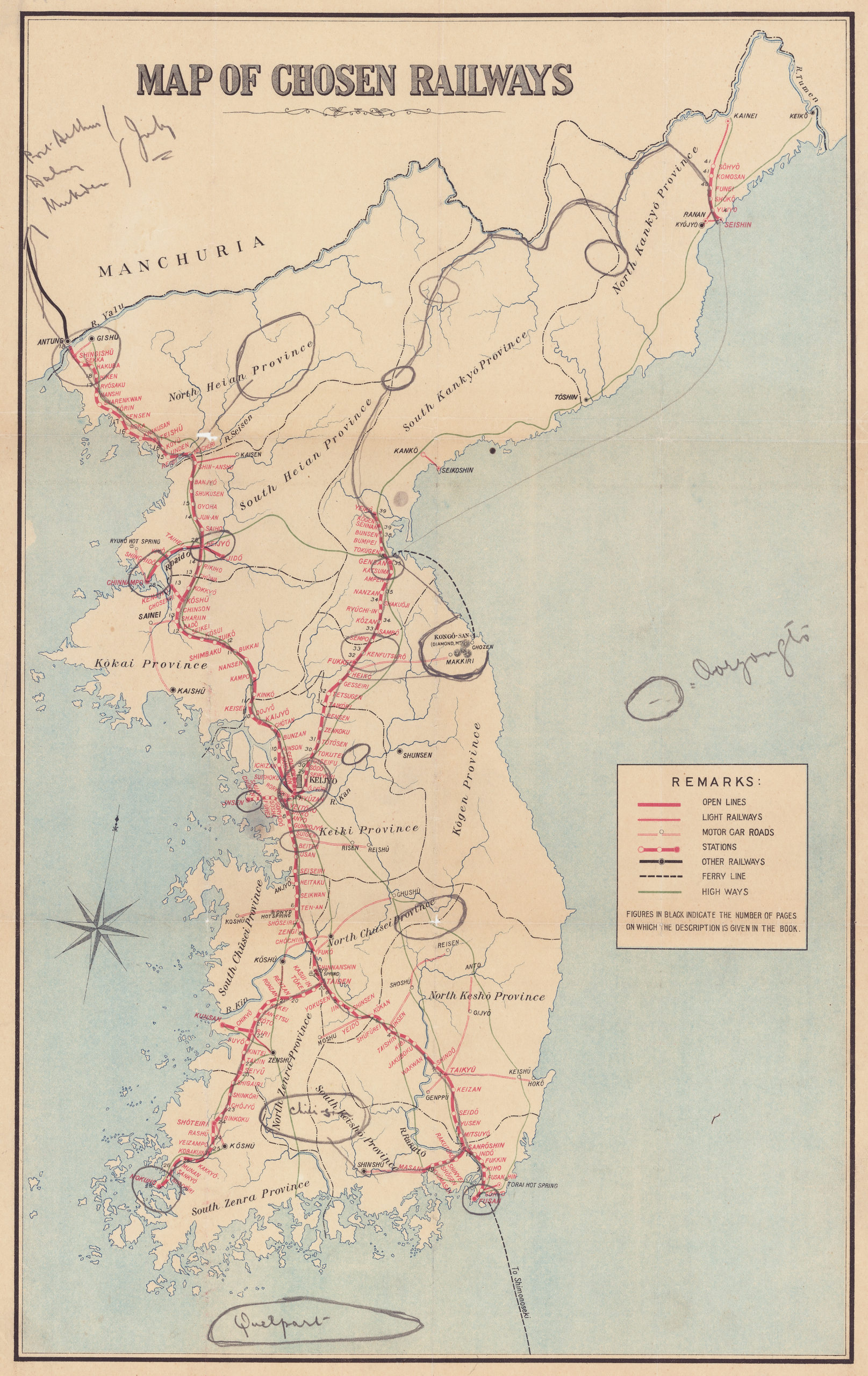

Unlike his experience in Japan, the Korean railway network was less well developed. This meant that once he reached the end of a line, Wilson had to proceed on foot. He remarks in a letter that “once off the beaten track, Korea is as hard a country to travel in as China.” He had underestimated the amount of time it would take to traverse the Korean countryside due to the summer heat and steepness of the terrain. His leg, which he injured in 1910 in China, also concerned him and slowed his pace.

Northeastern Korea

Wilson began his longest journey in Korea thus far on August 12. It took him to the far north and east of the country and covered about 500 miles in Hamgyeongbuk-do and Hamgyeongnam-do, North Korea (North and South Kankyo Provinces). After disembarking in Chongjin (Seishin), he made his way north to the Dumangang (Tumen) River on the Chinese border, following it west to it’s source.

Crossing the Baekdudaegan (Chang-pai-shan) mountain range, he picked up the nascent Yalu River and descended it for four days. He then turned south for fourteen days before finally turning east to reach the railhead north of Wonsan-si, Hamgyeongnam-do (Wonson).

In the Borderlands

The Korean-Chinese border territory through which Wilson traveled on this trip had not been widely explored by western botanists. He characterized the northernmost portions as boreal, in which winter temperatures dropped to -20 to -40F (-29 to -40C). He found fewer species of trees there than in the forests of Japan and China. The trees, primarily conifers, had not produced seed that season.

The species of larch common in the region (probably Larix gmelinii) impressed him. The trees grew straight, and as tall as 150 feet, with trunks 8-12 feet in circumference at breast height, but he hastened to add, “always and only on volcanic soil.” In a letter to Sargent he recommended them to American and European foresters.

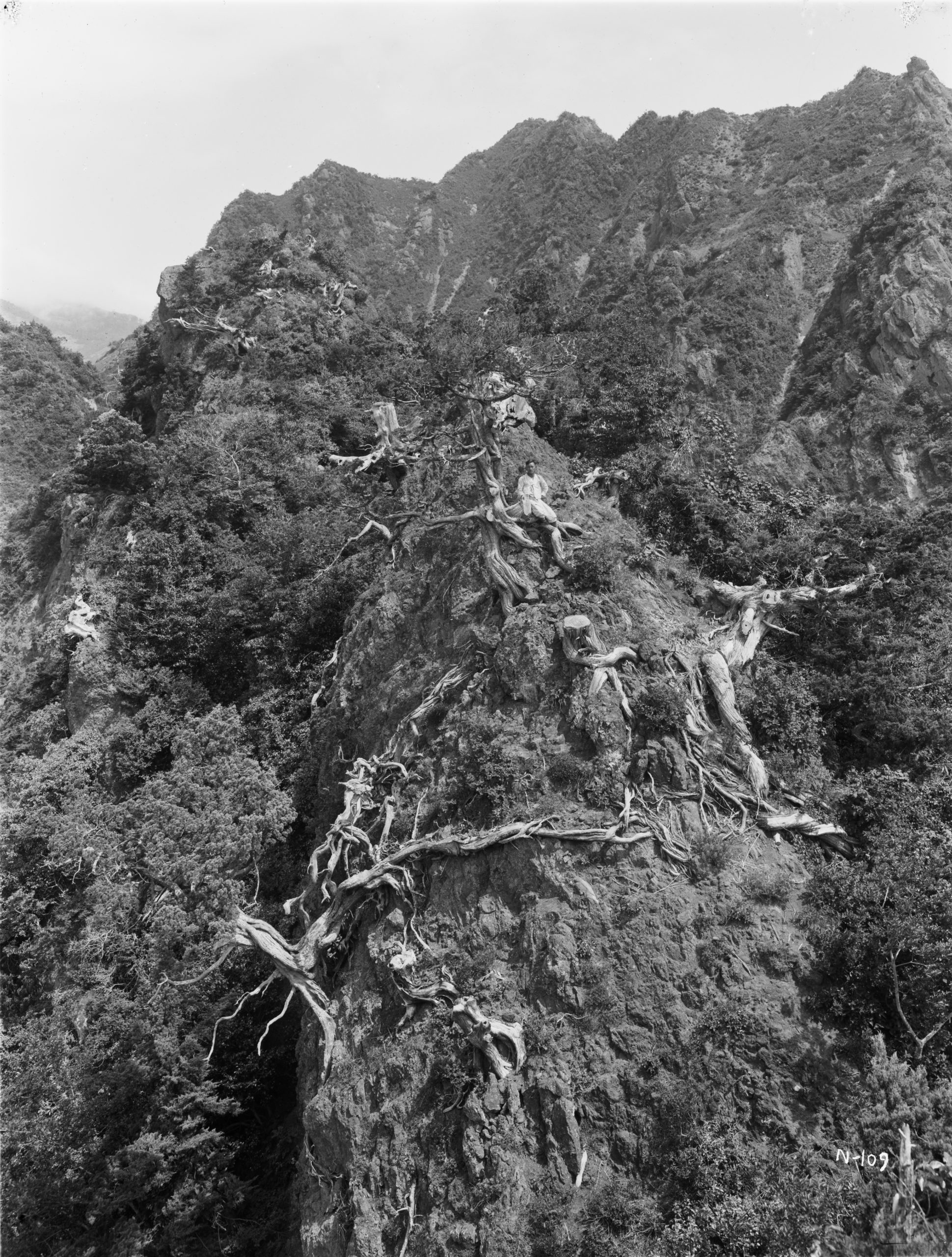

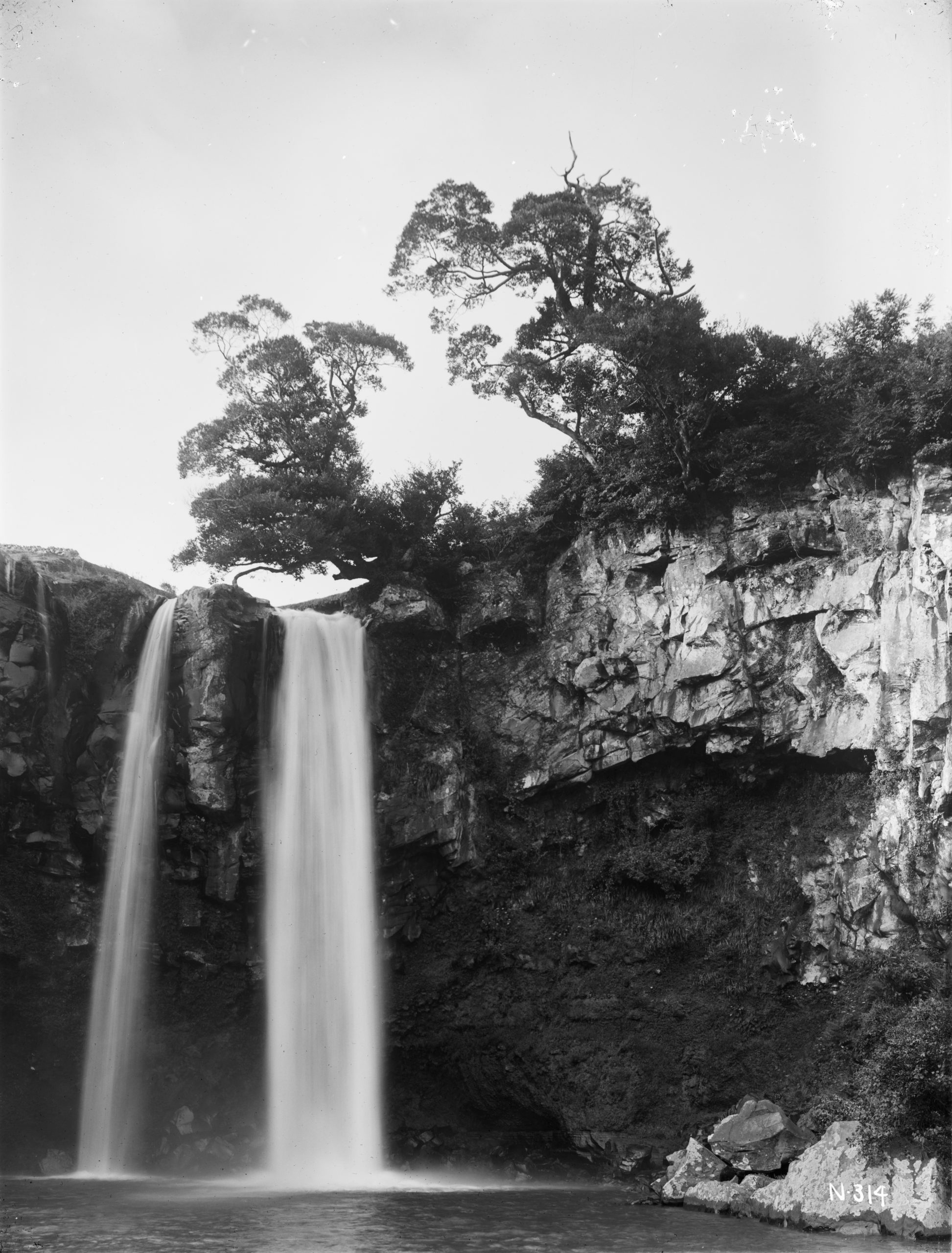

“Fortunate are those who look on the wondrous scenes and drink of the beauty and charm of ravine and dell, mountain top and cliff, cascade and pool, in the fairy land of Diamond Mountains.”

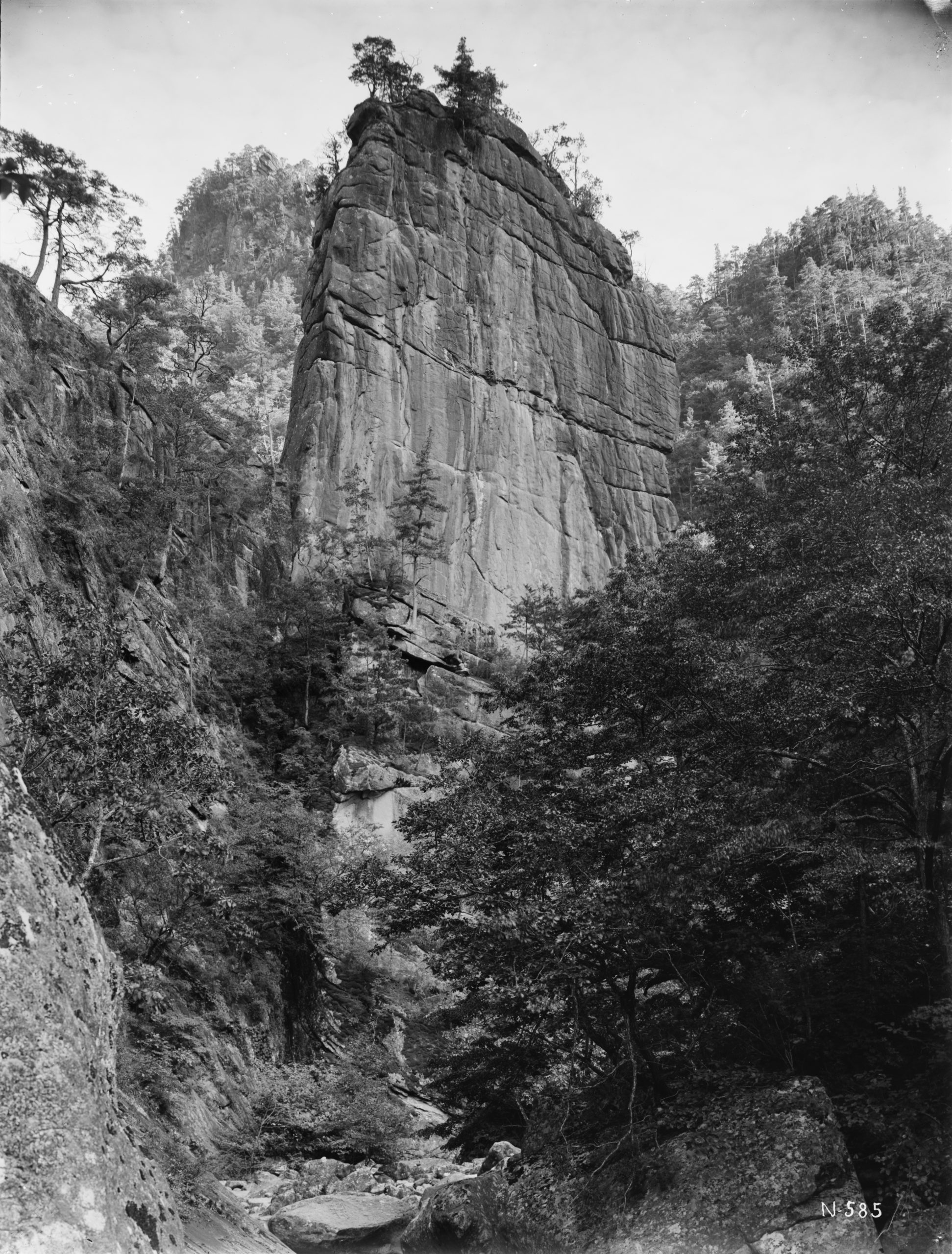

Geumgang-san

This long northern trip did not complete Wilson’s work for the year. In early October, he made a two-week visit to the Geumgang-san, Gangwon-do, North Korea (Diamond Mountains or Kongo-san), an area of great scenic beauty and stunning fall color. There, among many collections, he found two maples, Acer pseudosieboldianum and A. trifolium, in which he was particularly pleased, as well as several new taxa, Taxon: In biology, a taxon (plural taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. including an arborvitae (Thuja) and a Forsythia.

The beauty of the region enthralled him and his camera was busy as he photographed the dramatic landscape he saw. In his notes he gushed, “Kongosan drives a photographer to despair, for no sooner has he taken one superb view, than another seemingly more superb presents itself.”

Jeju and Jirisan

Wilson journeyed south to reach his final Korean collecting locations of 1917 to Jeju (Quelpaert) Island and the Jirisan (Chirisan) Mountains, both in modern South Korea. Again, Takenoshin Nakai joined him on Jeju, providing his assistance and knowledge of the local flora. This allowed Wilson to very quickly collect specimens of most of the woody plants found there.

Wilson’s eight-month sojourn in Korea was physically demanding but extremely fruitful. By his own reckoning, he traveled nearly 10,000 miles (16,090 kilometers), collected plant material from every type of Korean tree and almost every shrub, and took 216 photographs of what he saw along the way. He found fewer trees that had fruited than he might have hoped, but strongly recommended to Sargent that he return the next year to make further collections.

1918

Wilson’s explorations in 1918 covered nearly the whole of Taiwan in several trips, a survey of Tokyo area nursery companies, the selection of his top 50 Kurume azaleas, and a return for a bit more collecting in both Korea and Taiwan.

Taiwan

The flora of Taiwan is tropical and not generally hardy in the cold climate of New England, so Wilson’s goal for this three-month trip was to see and collect herbarium specimens, in particular from all the island’s conifers. Ryozo Kanehira, director of the forestry station there, provided every assistance, and Wilson praised him saying he was, “a very exceptional man, full of energy, enthusiasm and good will.” He arranged all the trips and also joined Wilson in the field for most of them.

At this time, Taiwan (known as Formosa) was a dependency of Japan as a result of China’s defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895.

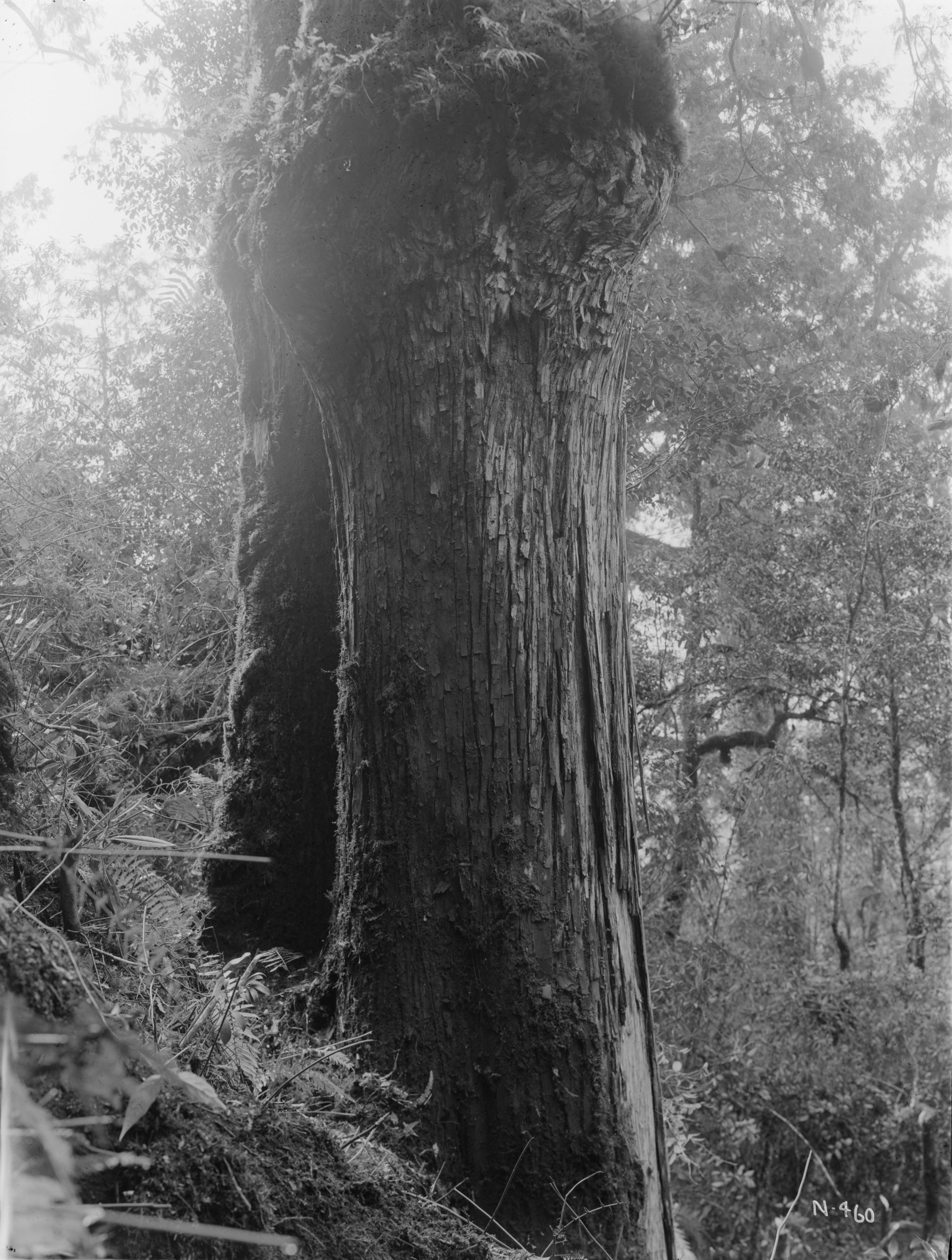

The Big Trees of Alishan

In mid-January 1918, Wilson arrived in Taiwan to begin a survey of the island’s flora. He traveled first to Alishan (Ari-san), where he described the forest “the finest, and the trees the largest I have ever seen.” There in the almost completely coniferous rainforest, he found enormous Taiwania cryptomerioides at the 7000-8000 foot (2133-2438 meter) range that towered up to 200 feet (61 meters) tall. Other notable taxa included the Taiwan cypress (Chamaecyparis formensis), the Taiwan hemlock (Tsuga chinensis), and Armand’s pine (Pinus armandii), which Wilson said grew larger here than on the mainland.

On this two-week expedition, he and his team collected about 12,000 specimens from 200 species, and he took 78 photographs. Once off the light railway system, Japanese Forestry Bureau officials guided him, and a team of about 40 assistants and porters over mountainous terrain that Wilson described as “steep and savage”. His only regret about this highly productive trip was that Sargent was not there to share it with him.

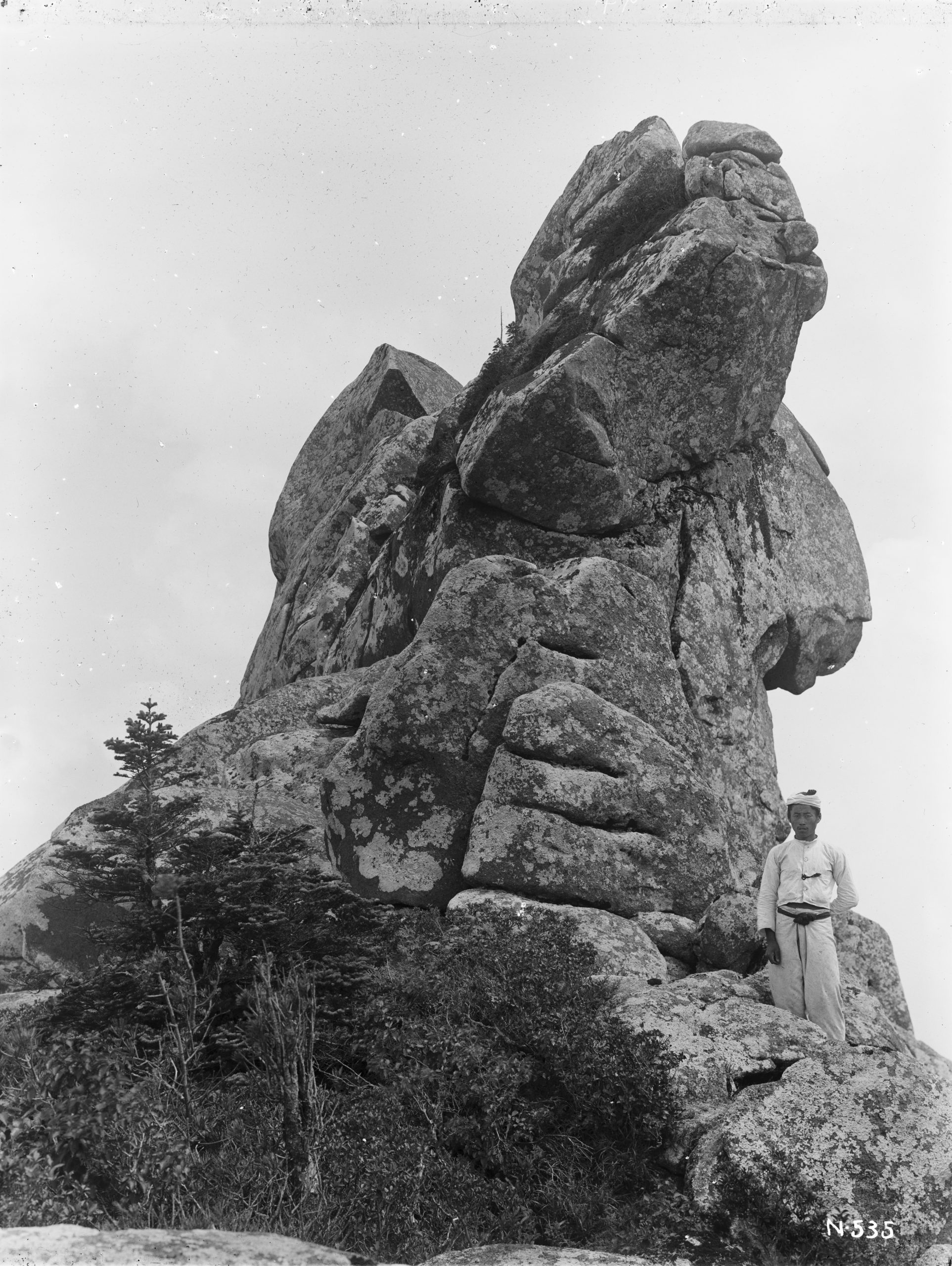

The Mountains of Central Taiwan

During the last week of February, Wilson made a short trip to the south of the country where to his disappointment, he found the natural flora nearly destroyed to make way for agriculture. A week later he began a much more satisfying visit to the mountains of central Taiwan. Due to security concerns, the Japanese forestry officials guiding Wilson closely guarded the team. The region was home to indigenous peoples who practiced headhunting.

On this trip Wilson and his party ascended the 11,000 foot (3350 meter) Mount Karaishu and explored the surrounding area. He found the climate to be drier than at Alishan, with the mid-range well forested. The high elevations (over 9,000 feet, 2740 meters) had grasses, junipers (primarily Juniperus squamata), and one of his target plants, the Taiwan fir (Abies kawakamii).

Into the Northern Mountains

The final leg of Wilson’s travels in Taiwan took place in the north of the country. In mid-March, he went out with the goal of collecting specimens of Cunninghamia konishii and several other conifer taxa. Poor weather hampered his efforts but he was finally able to collect specimens and photographs, as well as that of Chinese incense-cedar (Calocedrus macrolepsis).

Hunting for Pseudotsuga

After a short return to his base in Taipei he was off again in search of the Chinese Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga sinensis) on Mount Ritozan. The mountain was in the territory of indigenous peoples who were resisting attempts at acculturation by Japanese government authorities. Wilson’s team was closely guarded by a security detail of ten armed police. On their way to their destination, they followed a fortified, mined, electrified wire line that divided the territory of the indigenous people from the Japanese.

After four days hiking they finally found the object of their journey, a large Chinese Douglas-fir. It bore some old cones that Wilson collected for herbarium specimens but unfortunately the weather turned poor with dense fog and rain, making photography impossible.

The team found shelter for the night in a police hut. The next morning dawned clear and they returned to the tree. The denseness of the forest made photography difficult but after several hours of removing the overgrowth, he was able to secure some images of the tree. As soon as this was done, as if on cue, the fog rolled in and it began to rain.

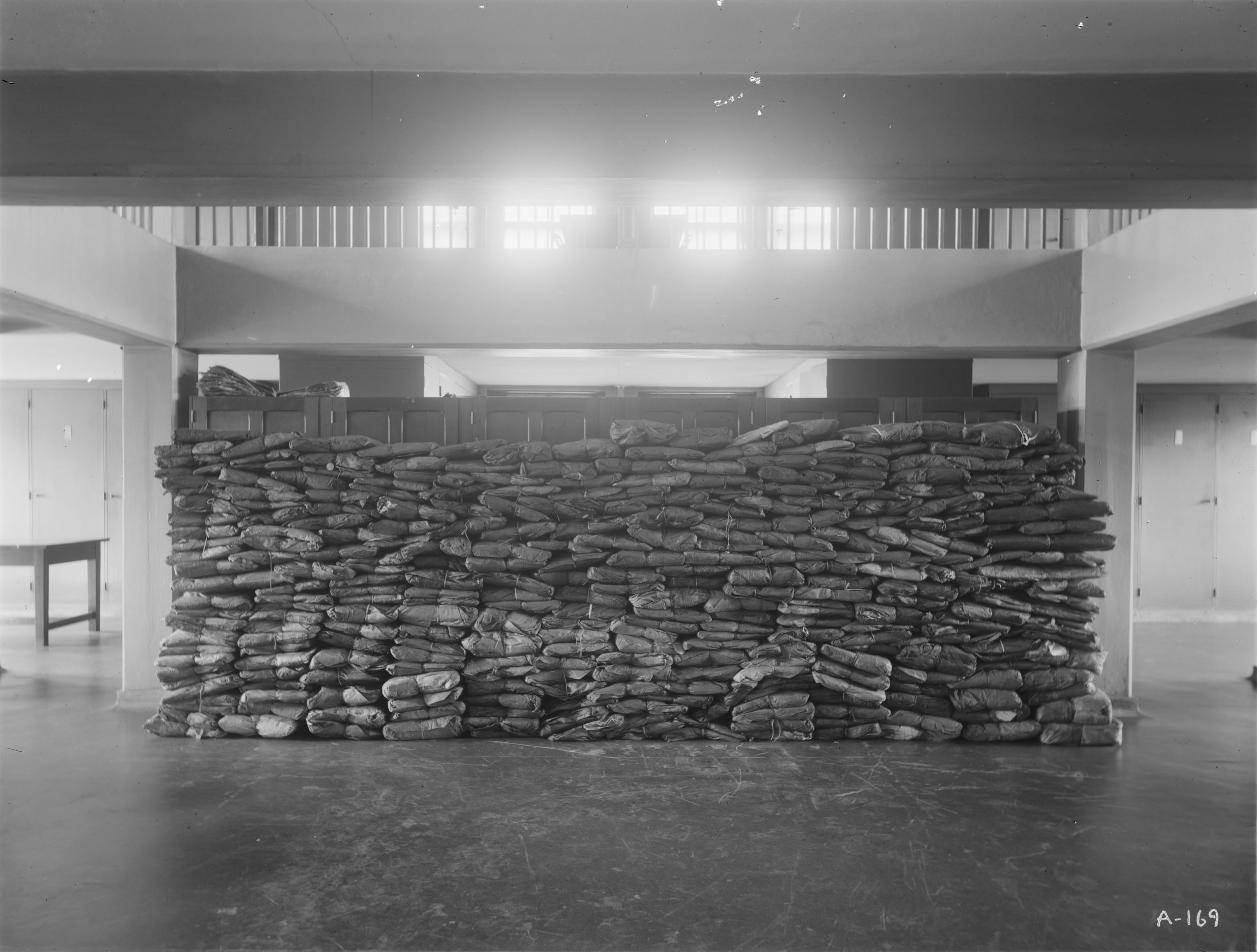

Wilson left Taiwan by ferry on April 15, extremely satisfied with the depth and breadth of his collections. Because of concerns over shipping his specimens by freight through the port of Kobe, he determined, “by hook or crook to take them with me. I packed them in baskets, small boxes, and crates of handy size but I confess that the wildest stretch of imagination could hardly regard them as legitimate passengers baggage.”

He resolved to return to the island in the fall to gather seeds.

Back to Japan

Kurume Azaleas

One of Wilson’s best known collections made during this expedition were the beautiful Kurume azaleas. In Kurume, Kyushu, he visited the nursery run by Kijiro Akashi. Akashi had devoted forty years to breeding azaleas from selections first developed by Motozo Sakamoto in the early nineteenth century. At the time of Wilson’s visit, Akashi had over 250 varieties in his nursery. Wilson chose what he thought were the best azaleas for color and hardiness, a selection known today as the “Wilson Fifty”.

On his return to Japan, Wilson took a well deserved rest for the remainder of April before embarking on May 2 for Kyushu. During this part of his trip, Uhei Suzuki, head of the Yokohama Nursery Company, joined him in exploring the area nurseries growing the Kurume azalea. They then continued on to Mount Kirishima, the location where the original plants were said to have been collected. There they found a profusion of azaleas growing on the windswept slopes. He and Suzuki collected plants with a variety of pink, salmon, magenta, and red flowers. In a letter to Sargent he gushed, “These Azaleas captivated me in 1914 and the more I see of them, the more infatuated I become.”

Wilson spent the remainder of the month visiting nursery companies in and around Tokyo. In his correspondence, one senses that he was somewhat let down by the experience. He notes a red flowered Witch-hazel (Hamamelis) but no other plants seem to have caught his eye.

Return to Korea

The Wilson family sailed for Korea in mid-June for a three-month sojourn. As a result of the Treaty of Brest-Livtosk that ended Russian participation in World War I, there were new restrictions on foreigners entering the country, as ex-prisoners of war attempted to flee Russia. On his arrival, Wilson soon called upon the local authorities to again get their assistance for more plant collecting, a request which was quickly granted.

His first trip during this sojourn in the country was a return to the Geumgang-san (Diamond Mountains or Kongo-san). A Buddhist sanctuary covered the area and as a result the forests had been well preserved. Wilson made a number of collections there and took 36 photographs. He noted in a letter to Sargent that the forests were changing from primarily conifers to broadleaf trees. Royal azaleas (Rhododendron schlippenbachii) dominated the undergrowth, and sported wonderful pure pink blossoms during his visit.

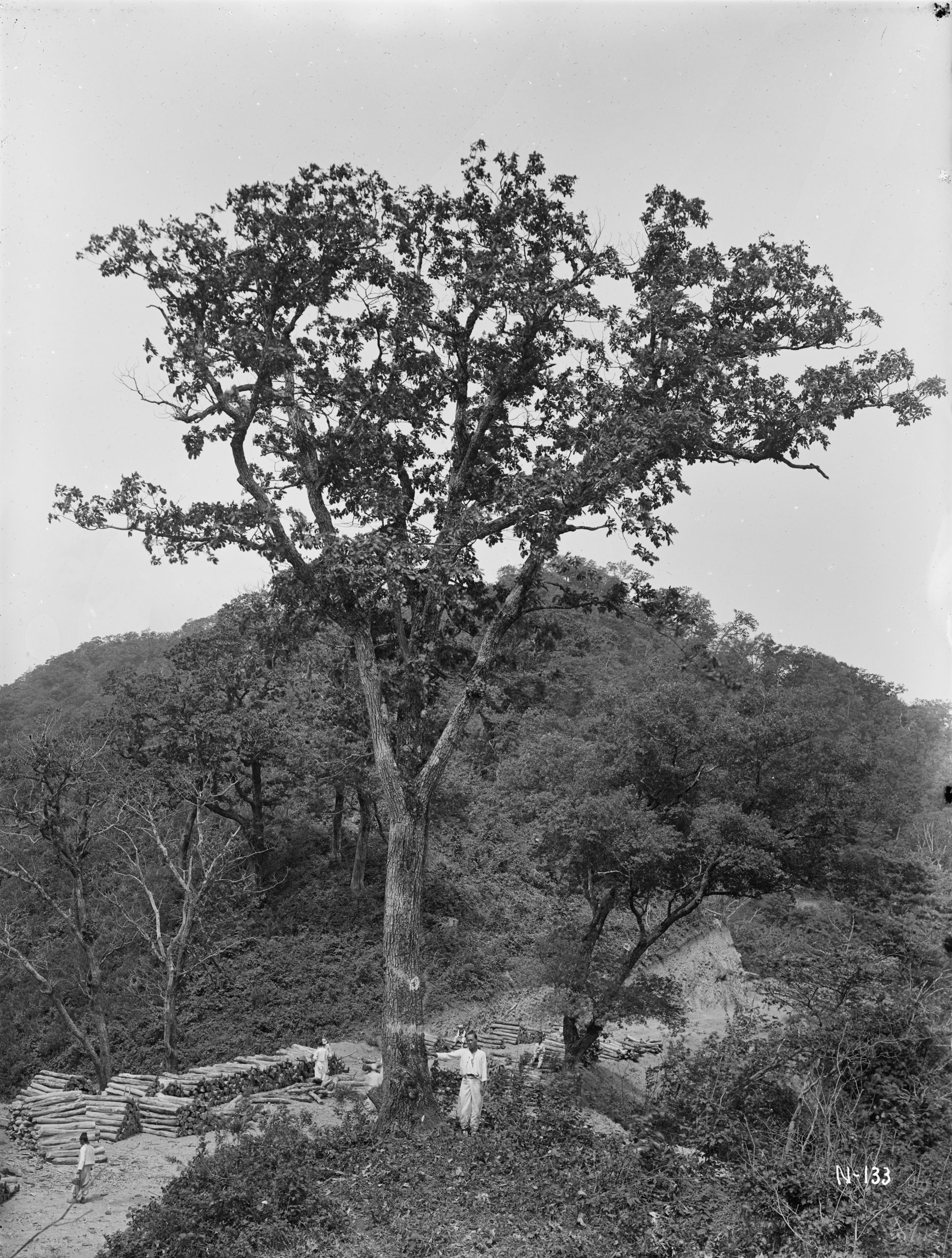

After a return to Seoul he was off at the end of July to the northwest part of the country. There he collected some herbarium specimens but little else. The object of his quest, an oak identified by Takenoshin Nakai (Quercus mccormickii) remained ellusive. In mid-August he traveled to south-central Korea, visiting the home area of the Koreanspice viburnum (Viburnum carlesii) and the Korean hornbeam (Carpinus turczaninowii). Then he returned to the northwest for another week of collecting.

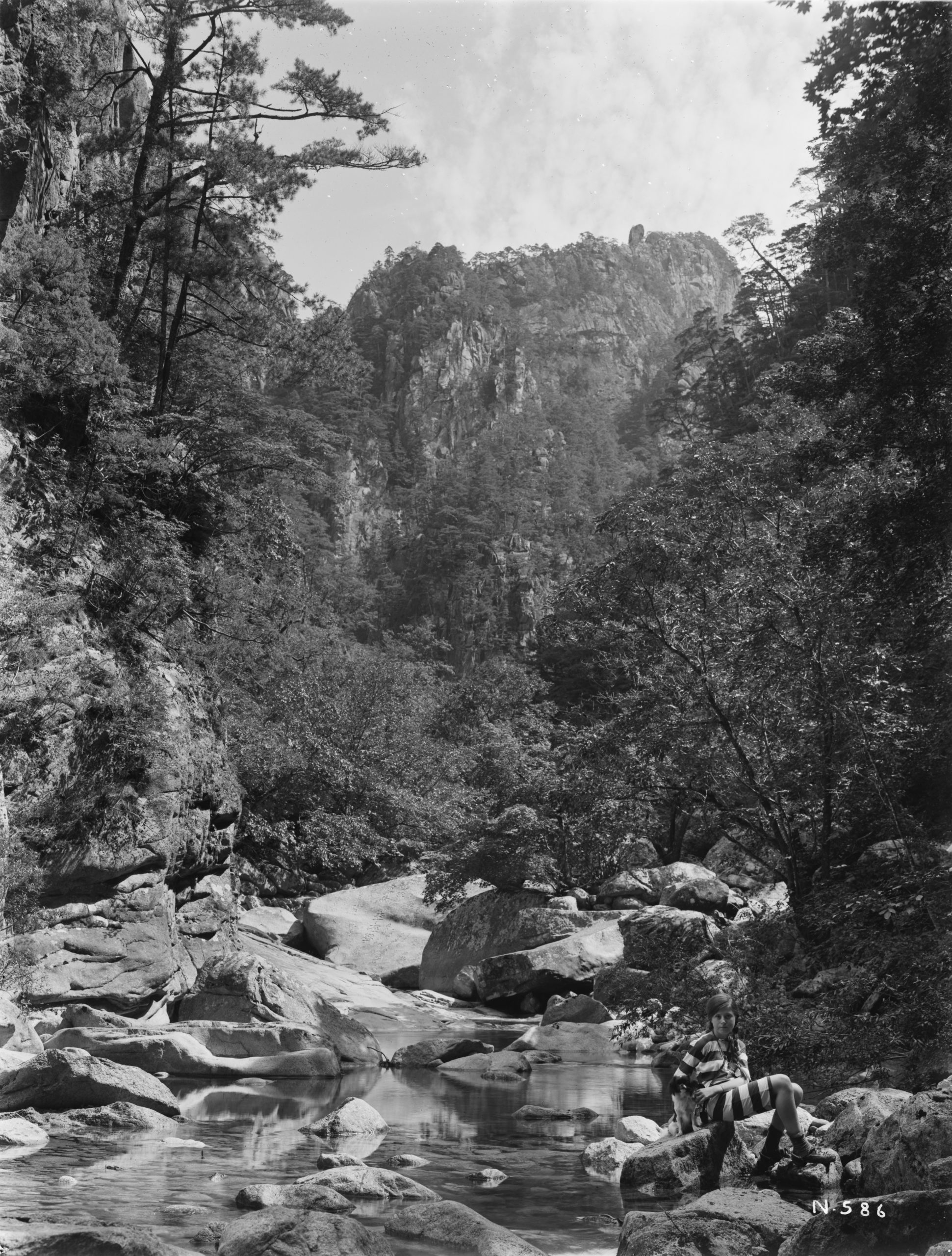

Geumgang-san Sightseeing

In early September, Wilson, his wife Ellen, and daughter Muriel, made a family excursion to the Geumgang-san. He did some collecting, numbers 10688-10756 in his notebook are recorded for this trip, but he also took some of his last photographs in Korea. There are some magnificent landscapes and tree portraits, as well as several of his daughter in a bold striped bathing costume posed on a boulder by a stream.

Back to Taiwan

Wilson spent October, November, and the start of December in Taiwan. He returned to Alishan where, in spite of the persistent rain, he collected seed from a number of taxa of conifers. From there, he and his party of eight police and 47 indigenous guards and bearers traveled east to Yushan (Mount Morrison) over terrifically steep and difficult terrain. Despite the hard travel he was genuinely sad to leave the magnificent forests saying that he was, “Grateful to have been privileged to view them and to have roamed through their depth.”

From Yushan he traveled overland to the south and then made his way up the eastern coast of the island. He traversed the limestone cliffs of the northeast, a sometimes dangerous journey, where he collected a small amount of seed and many specimens. After a short stop in Taipei he was off again to the central part of the island to collect seeds from several species of oaks and then to the northwest to an area of volcanic soils.

In mid-December, Wilson sailed to Japan and then on to Korea to bring back his wife and daughter. He spent the remainder of the month packing and preparing his collections for shipment.

1919

Wilson and his family planned to sail to America on January 6. Their departure was delayed until February however, due to a scarcity of ships.

The logistics of shipping all of the specimens, seeds, live plants, and photographs vexed Wilson very much. He began planning almost as soon as he had arrived in 1917. David Fairchild, head of the Office of Seed and Plant Introduction at the U.S. Department of Agriculture, sent detailed instructions in June 1918 on packing and shipping. New U.S. government regulations passed in the wake of the chestnut blight crisis added to his headaches and made for more red tape.

He desired to send his collections by express to Boston but until the last minute worked under the assumption that they would have to pass through U.S.D.A. headquarters in Washington, D.C. Just before his departure, Wilson learned from the U.S. Counsel in Yokohama that the restrictions had been lifted. He seized the moment and immediately sent all his glass plate negatives and herbarium specimens by express to Boston.

Back in Boston

Wilson’s 1917-1919 expedition to eastern Asia yielded a collection of over 30,000 dried specimens. Those specimens represented over 3000 different species. He also took over 700 photographs of the Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese flora and landscape. Instead of waiting to develop his photographic plates when he returned home as he had done in the past, Wilson had the plates developed in Japan. He stored them, along with his dried materials, in a Yokohama Nursery Company warehouse until his departure.

Over 100 plants from this trip, or descendants of those plants, flourish on our grounds today. His Korean collections maybe seen in ArbExplorer here. All of his Japanese collections from this trip as well as his 1914 expedition may be seen here. They primarily arrived as seeds which were grown by Arboretum propagator William Judd.

Dig Deeper

We are fortunate to have Wilson’s letters to Charles Sargent from this trip. A number from the Taiwan portion were published in a recent Arnoldia. They are available in their entirety in the finding aid to Wilson’s archival collection.