1

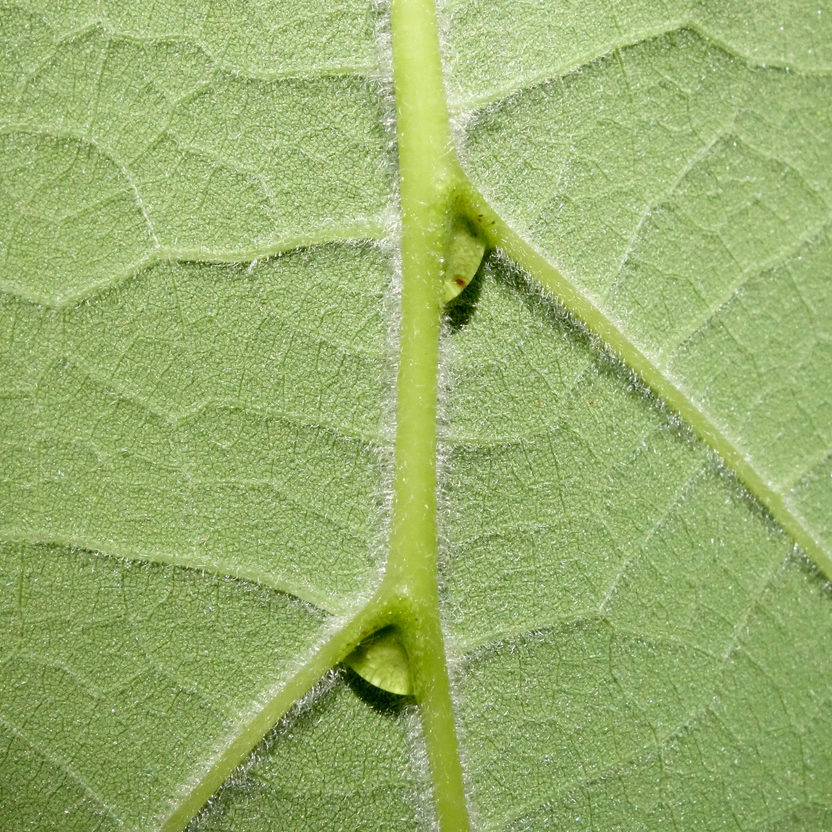

Painted Maple

Acer mono

-

Gray mature bark with vertical ridges. -

Young five-lobed leaves and inflorescences.

An architectural masterpiece

As only the eighth director of the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University in its nearly 150-year history, I wake up every day amazed by my good fortune. I also live just two blocks from the grounds (where else, of course?). As such, I spend much time wandering the Arboretum, admiring the plants, and taking in all that nature has to offer throughout the year.

Each of the plants I have selected for this tour is associated with a wonderful memory of a moment when two organisms—a person (me) and a tree (not me)—connected in time and space. These plants have inspired me and drawn me deeper into the living collections. I hope this tour will lead you into a lifelong relationship with the more than 16,000 woody plants that call the Arboretum home.

Let’s start with one of my absolute favorite specimens in the collection, the painted maple (Acer mono), accession 5358*A. This tree began its life in Boston as seed shipped from the Imperial Botanic Garden in Tokyo in 1902. Imagine it germinating in the Arboretum’s greenhouses the following spring, only an inch tall, with a pair of small seedling leaves emerging from the soil.

Some four or five years later, the young sapling would have been ready to be planted in the earth. A spot was picked, a hole was dug, and the painted maple then spent more than a century growing into the masterpiece before you. Take it in from different angles, at different times of the day, and during different seasons. This tree is graceful, majestic, sublime.

2

Snakebark Maple

Acer rufinerve

-

Characteristic colorful, striped bark. -

Swelling axillary buds in opposite arrangement.

Bark like a snake

The Arnold Arboretum hosts the finest collection of maples of any botanical garden or arboretum in the world. In New England, we might come up with a short list of maples familiar to us: sugar maples, silver maples, red maples. But maples (genus Acer) are a highly diverse group of trees with roughly 130 species around the Northern Hemisphere and most are native to temperate East Asia.

There’s a good reason the Arnold Arboretum has such an amazing collection of maples: we’ve been collecting plants in China, Japan, and Korea for nearly 150 years. After all, this is a museum of trees! Among my favorite maples are a small group of species called the snakebark maples, all but one of which are native to Asia. As you might guess, the snakebark maples have gorgeous smooth barks with white, waxy vertical stripes. The bark can resemble the color of limes, or of orange and grapefruit rinds.

Every winter, when the Arboretum reveals its bones, I make it a practice to go and behold the bark of these wonderful trees, including redvein maple (Acer rufinerve), Manchu striped maple (Acer tegmentosum), and Father David’s maple (Acer davidii). Run your hand along the bark and take in its smoothness and coolness. These maples are some of the greatest treasures of temperate Asia.

3

Oriental Oak

Quercus variabilis

-

Narrow newly emerging leaves.

The majestic oaks

Every autumn, I return to visit the venerable Asian oaks, and in particular, the oriental oak (Quercus variabilis).

I am drawn to these trees because of their deeply furrowed bark and their smooth brown fruits (the “acorn”) with over-the-top caps (the “cupule”). The cupules, with their unruly, curled scale leaves, end up all over the ground under each tree after squirrels pillage the acorns and carry off the good parts.

I also enjoy the fact that while autumn is everywhere around us, the leaves on this species of oak haven’t even begun to lose the deep green of summer. These trees are stoic—no reds, no golds—biding their time before their leaves turn a magnificent tan and scatter to the wind.

The first of this species to join the Arboretum’s living collections was gathered by the first director of the Arboretum, Charles Sprague Sargent, during his travels to Japan in 1892. Later specimens would come to the Arnold from collecting expeditions to China in 1905, 1908, and 1994. Indeed, the seed for the tree in front of you was collected in South Korea on an Arboretum expedition in 1977.

4

Cultivar of Panicle Hydrangea

Hydrangea paniculata ‘Praecox’

-

Large, showy, cone-shaped inflorescences. -

Multiple stems with flaky mature bark. -

Simple leaf.

Breathe deeply

There are certain times of the year when the Arnold Arboretum must be inhaled to get the full experience. During summer, aromatic compounds released from the flowers of linden trees (Tilia) and the magnificent panicle hydrangea (Hydrangea paniculata) are especially intense. Come July, two extraordinary accessions of panicle hydrangea, 14714*A and 14714-1*A, are covered in white flowers, several weeks before many other members of this species.

Accession 14714*A arrived in Boston in 1892 as a seed collected by Charles Sprague Sargent, the Arboretum’s first director, during his expedition to Japan. It has grown in this spot (once it graduated from the nursery) ever since. Accession 14714-1*A is a literal “chip off the old block,” propagated as a cutting from 14714*A in 1905.

A wonderful thing about hydrangeas is their floral dimorphism. Each plant produces two distinct types of flowers: the fertile flowers, smaller and more numerous, and the showy flowers, less numerous and sometimes referred to as sterile flowers (even though they are often perfectly fertile!).

Many hypothesize that the evolution of showy “sterile” flowers in hydrangeas was driven by the benefits of attracting more pollinators to the inflorescences—or as Charles Darwin put it in 1877, “by rendering the flower-heads conspicuous to insects.” I buy it.

5

Northern Catalpa

Catalpa speciosa

-

Long, straight young stems. -

Long, peapod-like fruits.

The centenarian from Illinois

This northern catalpa began life in Waukegan, Illinois, in the nurseries of the great catalpa promoter and grower Robert Douglas. Douglas recognized the outstanding qualities of the species—fast growing, rot resistant, tolerant of poor soils—and saw its potential as a major source of timber. Douglas planted over two and a half million seedlings of northern catalpa in the American Midwest. Two of his trees made their way to the Arboretum in 1886.

Catalpa trees used to be a common street tree in America. In the middle of summer, after peak flowering for most temperate trees has passed, catalpas put on a magnificent show of flowers with wild coloration—purple and orange spots, tiger stripes—and with fringed and fused petals.

Today, people tend to prefer “clean” trees, meaning trees that don’t drop an abundance of “messy” fruit each fall. Catalpa trees, after they flower, form a lot of fruits, each about a foot and a half long, like a vanilla bean. Most people prefer not to have 10,000 peapod-like fruits rotting on the sidewalk. I think that’s a pity. Nature can be messy, and it’s nice to have a bit of that mess right in your own yard!

6

American Sweetgum

Liquidambar styraciflua

-

Deeply furrowed bark. -

Large colorful buds.

Phenomenal winged bark and fruits that amaze

The tree you are about to meet is the very first tree I fell for at the Arnold Arboretum, way back in 2009. Early winter had arrived and the trees had lost their leaves. I wandered in an unfamiliar landscape on one of my first visits to the grounds of the Arnold Arboretum. Heading up Bussey Hill, I was completely dumbfounded by the sweetgum tree (Liquidambar styraciflua) before you. I’ve seen plenty of sweetgums in my day, but this one caught me up short.

Sweetgums display a form of winged bark in which panels of corky ridges develop along the length of the woody branches. But this sweetgum appears to be on steroids! The architecture of the tree seems strange, stunted, and weirdly branched. A close look reveals an unusual amount of corky ridges (wings) forming along the woody branches.

Along with their extraordinary bark, the inflorescences and fruits of sweetgum are a wonder throughout the year. Flowers are unisexual (having either male or female parts) and form in dense clusters in the spring, with female flowers showing off some amazing curly stigmas (the structure that receives pollen). With time, the clusters of female flowers (inflorescences) develop into spikey woody infructescences, which hang on the tree long after they have shed their seeds.

This sweetgum came to the Arboretum in 1979 as a seed. Its mother was apparently just as “wingy.” One of our sharp-eyed plant collectors spotted it in a farm field in Missouri and took the liberty of liberating a few seeds.

7

Bigleaf Magnolia

Magnolia macrophylla ssp. macrophylla

-

Large simple leaf. -

Red aggregate fruit.

The Arboretum’s largest flowers

The Arboretum has a wonderful magnolia collection. Most visitors will be familiar with the early flowering species that put on a dramatic show near the Hunnewell Building every spring. But some magnolia species flower in late spring and even into summer.

My favorite is the bigleaf magnolia (Magnolia macrophylla), an amazing species native to the southeastern United States. Our specimens are tucked away underneath the hickory collection. The bigleaf magnolia not only has massive leaves (the largest simple leaves of any temperate tree), it also has enormous flowers, which span a foot and a half across when fully open in June. Why in the world would a plant have a flower that big? The answer is: I have no idea. But it is a beauty to behold.

As with all magnolias, flowering is a wonderfully choreographed process. On the first day, the flower opens and performs its female function by receiving pollen. At this stage, the flower appears like a narrow champagne flute, tall and erect. On the second day, pollen is released from male structures (stamens), and tepals (petal-like parts) open fully, yielding a large, dinner-plate-sized flower.

This sequence of pollen reception and pollen release—one of many clever strategies that have evolved to prevent self-pollination—reminds us that plants express gender in very clever ways. The first book written on this very subject was penned by none other than Charles Darwin in 1877.

Want to dig deeper?

Explore the Bigleaf Magnolia Plant Bio

8

Highbush Blueberry

Vaccinium corymbosum

-

Green simple leaves. -

Developing fruit in summer.

A very old pair of highbush blueberries

The Explorers Garden is filled with the greatest hits of the Arnold Arboretum, specimens highlighting the institution’s 150-year history of bringing magnificent woody plants from around the Northern Hemisphere to Boston.

Showstopping plants abound at every turn, including the two oldest Franklin trees (Franklinia alatamaha) on the planet (accessioned in 1905); a large patch of royal azaleas (Rhododendron schlippenbachii), some going back to 1905; a stunning Chinese fringe tree (Chionanthus retusus) at the end of Chinese Path (a 1901 gift of the Imperial Botanic Garden in Tokyo); and the first two dove trees (Davidia involucrata) grown at the Arboretum, accessioned in 1904 and 1911.

But beauty can be found in even the most seemingly mundane plants. The highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum, accession 1951*B) before you is one of a pair of blueberries that came to the Arnold Arboretum in 1883. While kind of scraggly, these two plants sport lovely green leaves, beautiful urn-shaped flowers in the spring, and vibrant young blueberry fruits through early and mid-summer.

Both shrubs were collected by Jackson Dawson, who served as the Arboretum’s first plant propagator—a post he held for 43 years. In 1883, Dawson, traveling atop a horse-drawn cart, discovered these plants in a nearby woodland and collected them.

True, these two highbush blueberries did not travel far to arrive at the Arboretum. No team of plant collectors risked their lives on remote mountainsides in China, Korea, or Japan to obtain them. They braved no long journey by river, sea, and transcontinental railroad to arrive in Boston—just a short ride to the Arboretum in a cart. They are “just” a couple of very old blueberries from around the corner, after all. They persist and they are beautiful.

Want to dig deeper?

Explore the ‘Dunfee’ Highbush Blueberry Plant Bio

9

Twisted Beech

Fagus sylvatica ‘Tortuosa’

A wonderfully twisted tree

The Arnold Arboretum hosts more than a dozen cultivars of European beech, including purple-leaved, cut-leaved, and weeping forms. But none of these horticultural deviants comes close to the dramatic twisted European beech, Fagus sylvatica ‘Tortuosa’. This magnificent specimen came to the Arboretum in 1888—a gift from Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, and a reminder that gardens around the world are always sharing their botanical bounty.

Instead of growing straight up to the sky, like a regular European beech, the twisted beech has branches that grow in spirals and then droop. Over time, the tree takes on the shape of a hemisphere. In autumn, standing under the canopy is akin to entering a medieval cathedral with magnificent (and ephemeral, in this case) stained-glass windows filtering the light.

Look up at the winding shoot system, and enjoy the solitude of being alone with a single beautiful organism amidst a sea of trees, all within an urban oasis. Winter brings the magnificent twisted forms of the branches to the fore, and spring bud break delights with the light green of newly born leaves.

There are plenty of other horticultural delights associated with pendulous or tortured forms–weepers, if you will—and you can find many of them scattered across the Arnold Arboretum.

10

Table Mountain Pine

Pinus pungens

A tree to lie under and look up

The pine collection at the Arnold Arboretum is among the subtlest of our collections, passing through the seasons without the showiness of a riotous spring floral display or the kaleidoscope of autumn leaf colors found among deciduous brethren. Rather, each and every day, pines are measured in the subtle hues of the green of their needles, the textures and shades of bark, and the slow maturation of their seed cones.

A favorite destination among the pines is a set of three centenarian Table Mountain pines (Pinus pungens, accessions 10706*A, *C, and *E) that hail from the Appalachian Mountains. The seed cones of this species have amazing thorn-like structures protruding from each seed scale.

Table Mountain pine is serotinous, which means that it holds its seed-bearing cones for years, tightly closed, until wildfire arrives. The heat of the fire opens the cones, releasing the seeds within. This beautifully evolved mechanism ensures that stands of Table Mountain pines can readily repopulate their native habitats, which are subject to natural episodic fires.

When you visit these trees, be sure to take in the whole canopy from underneath (start with accession 10706*A, my favorite). Lie down, look up, and you will see a cloud of hundreds of old seed-bearing cones from the last decade silhouetted against the sky. The first time I tried this, it caught me totally off guard, in the best possible way! It will do the same for you.

11

Lacebark Pine

Pinus bungeana

-

Mature seed cone. -

Pollen cones swell in early spring. -

Vegetative buds stretch out in spring. -

Peeling bark, recently fallen.

A pine like no other

Among the 37 different species of pines that live at the Arboretum—totaling more than 1,000 accessioned trees—one species, in my opinion, rises above them all: the lacebark pine (Pinus bungeana), a native of China.

Nothing can exceed the dramatic bark of the lacebark pine which, in winter, flakes off in large puzzle-shaped pieces. A single trunk may present a stunning spectrum of colors, including avocado, grapefruit rind, crimson, silver, orange, and lime.

Look closely, and you may even notice that the north- and south-facing sides of the trunk differ in their color schemes (north tends to show a more silvery white). In the wild, lacebark pines may live for a thousand years or more. Here at the Arboretum, our oldest specimen—the one before you (accession 663-49*C)—joined the living collections in 1949.

12

Ginkgo

Ginkgo biloba

-

Fan-shaped leaves turn from green to a brilliant gold in autumn. -

Gray, plated bark, often covered with lichen.

Meet a female ginkgo tree

The ginkgo tree (Ginkgo biloba) is the last of its kind, the sole remaining species of an ancient lineage that once grew throughout the Northern Hemisphere. Today, this species persists in the wild in only a few small, dispersed populations in China. Nevertheless, ginkgoes are a very common street tree; their disease resistance and remarkable ability to thrive in hostile urban environments are legendary.

But there’s a catch. These days, trees planted in yards and city streets are always male. Ginkgo is dioecious—individual trees either bear seed (female) or pollen (male). Trees sold in the horticultural trade are always male, created by cloning other male trees.

There is a good reason for this gender bias: the seeds of female ginkgo trees contain copious amounts of butyric acid (which smells like vomit), and who wants that on their sidewalk underfoot every autumn?

Such is not the case at the Arnold Arboretum, where most of our ginkgo trees were grown from seed. Trees propagated this way reflect a near 50–50 male-to-female ratio. The venerable female ginkgo tree at Walter Street Gate (accession 14670*A) was grown from a seed received from Korea in 1904. In early November, hang around for a few minutes to take in the magnificent gold of autumn leaves (which fall over the course of only a few days) and the overpowering stench of mature seeds. Intense but worth it!

Want to dig deeper?

Explore the Ginkgo Plant Bio

13

Honey Locust

Gleditsia triacanthos

Armed and dangerous

The absolute best thorns to be found at the Arnold Arboretum are in the collection of honey locusts (genus Gleditsia) at the summit of Peters Hill, the second highest point in Boston. Along with these wonderful trees, those who visit will find a marvelous view of Boston’s skyline.

Some varieties of honey locusts make fine street trees, and can be found throughout the city. Cultivars used for this purpose have been selectively bred to lack the incredible thorns of the native species—essentially “declawing” them and making them much safer for passersby. We aren’t having any of that at the Arnold Arboretum. Our honey locusts are armed and dangerous.

One of my favorite honey locust trees, Gleditsia triacanthos (accession 1237-79*C), sports thorns that range up to a foot in length and could easily do some serious harm to the careless observer—so stay alert!

If you like this kind of armature, drift to the west on Peters Hill, and you will find many additional species of honey locust trees, including some with trunks near fully hidden by a thicket of colorful thorns.