Hiking through the hot, dry canyons at the base of the Sierra La Laguna peaks in Baja California Sur, Mexico, it is impossible to miss the beautiful arroyo oaks (Quercus brandegeei). The trees border the banks of the seasonal streams (or arroyos) like kneeling giants washing their limbs in the refreshing water. What is less obvious is that these represent a relict species that can only be found here, along the riparian zones of the Sierra La Laguna Biosphere Reserve, a biodiversity hotspot with high levels of endemism and great beauty. Each November, the tree canopies fill with elongated acorns that cause a lively commotion as birds, beetles, and rodents frantically eat the fruit on the trees and underneath. Ranchers value the trees too, frequently building corrals under their merciful shade and collecting acorns to feed livestock. However, populations of the arroyo oak are declining. There is no evident seedling regeneration, and the remaining trees are all more than one hundred years old. Until recently, the cause for decline was mostly unknown.

Across the globe from the Sierra La Laguna, Mount Mulanje—known as the “island in the sky”—rises from the plains of southeastern Malawi with such sheer contrast that it creates its own climate and flora. Best known and most impressive of the forest trees is the cedar that takes its name from these mountains. The Mulanje cedar (Widdringtonia whytei) is highly valued for its durable and fragrant timber, but due to overexploitation and illegal logging, the cedar has reached the point of near extinction. A similar fate is faced by a rare magnolia (Magnolia grandis) found only in the forested limestone mountains of southern China and northern Vietnam. With its large, leathery leaves growing to over a foot in length, this magnolia coexists in tiny forest fragments with other critically endangered species, including the strikingly unique Tonkin snub-nosed monkey. Recruitment of new seedlings is impaired by local agricultural practices in which farmers clear vegetation before planting cardamom and repeatedly weed out the magnolia to maintain their crop. Fewer than three hundred adult trees remain in small, isolated populations.

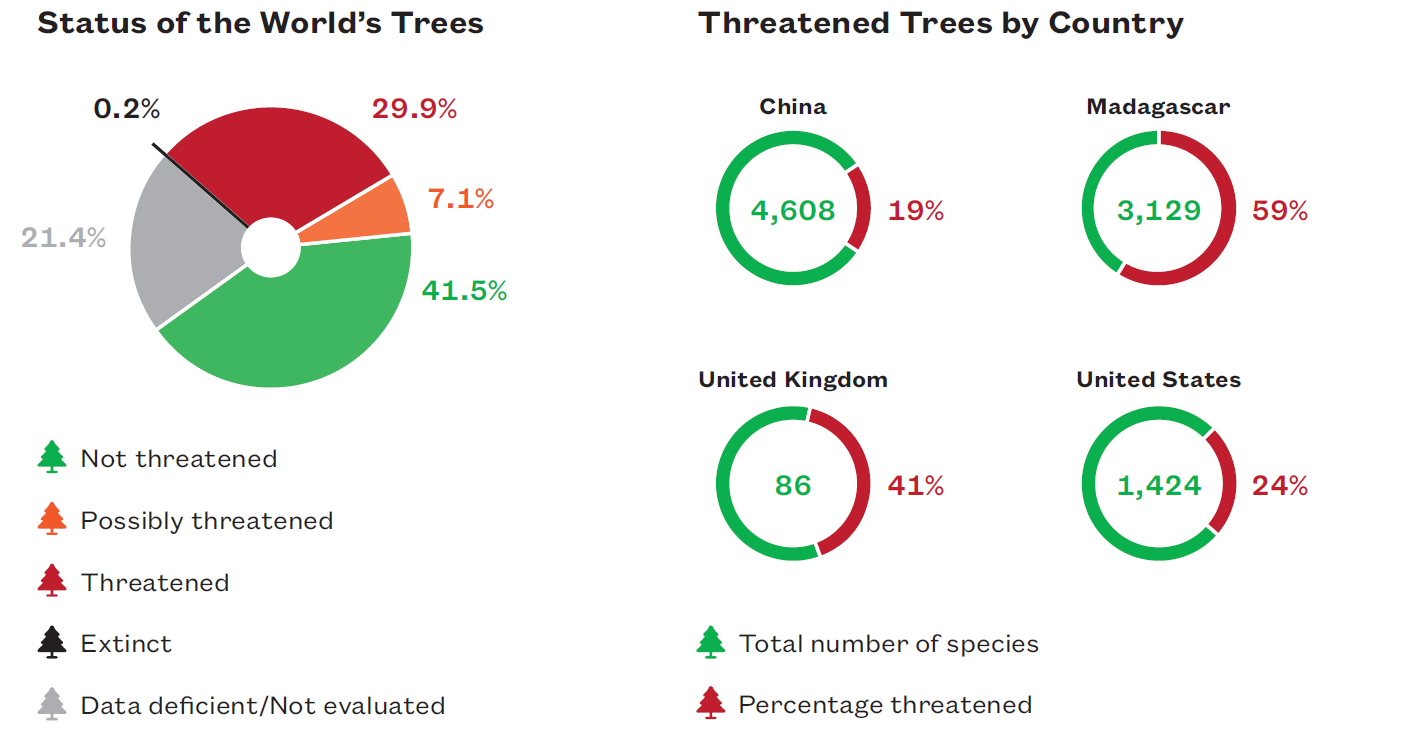

The loss of trees is a global problem. Evidence of declining populations, illegal logging, lack of regeneration, and new pests and diseases has been looming over our heads for decades. Until last fall, however, the complete picture of the status of the planet’s tree diversity was unknown. The State of the World’s Trees, published in September 2021, shares the results of the Global Tree Assessment—the first conservation audit of most of the world’s nearly sixty thousand species. The results show that 30 percent of all tree species—more than 17,500 species—are threatened with extinction. That’s more than double the total combined number of globally threatened mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians.

The Global Tree Assessment also reveals that at least 142 tree species are recorded as extinct. Losing even a single species can have severe consequences for an ecosystem. As primary producers at the base of the food chain, plants, including trees, are the building blocks of ecosystems—essential to all life on this planet. Myriad species of plants, animals, and fungi are intrinsically linked to trees, often interacting within complex and fascinating relationships that both parties depend on for survival. In addition, individual tree species play numerous economic, ecological, and cultural roles. We depend on trees in our everyday lives—they provide us with food, timber, and medicine. According to the assessment, at least one in five tree species has a recorded human use, and many have a variety of different uses. While the challenges and scale of the problem in maintaining tree species diversity are significant, we can do something about it.

A Global Campaign

The State of the World’s Trees is a sobering reminder that trees need our help. The Global Trees Campaign is co-led by Botanic Gardens Conservation International (BGCI) and Fauna & Flora International (FFI). Through this e ort, researchers, conservationists, and on-the-ground partners have been working together since 1999 to reduce threats and secure or recover target populations of threatened tree species through in situ action. Since its establishment, the campaign has worked to conserve over four hundred threatened tree species in more than fifty countries, and the team has trained more than ten thousand people in tree conservation skills.

Botanic gardens and arboreta have been vital partners in this e ort. Since 2017, for example, The Morton Arboretum, near Chicago, has led a Global Trees Campaign project that aims to safeguard the arroyo oak (Quercus brandegeei) of Baja California Sur. Researchers collected genetic, phenological, and ecological data on this endangered species to explore the causes of decline and identify conservation and management actions needed to save it from extinction. The team established fenced exclosures to quantify the effect of grazing and trampling by free-roaming livestock on seedling survival and growth. They found that cattle and goats eat the seedlings while pigs eat the acorns—a combination that prevents any natural regeneration from occurring. To combat these threats, Mexican scientists, land managers, ranchers, and international experts are working together to implement a management plan for this species. Among their actions, the team has conducted plantings within fenced areas to boost population recovery; they have encouraged ranchers to adopt oak seedlings and plant them within their fenced gardens; and they have worked with land managers to establish larger grazing-free zones within the reserve.

As illustrated by the work safeguarding the arroyo oak, effective conservation should be informed by accurate baseline information, including a thorough understanding of the species biology, specific threats, and potential actions to mitigate and reverse the decline. Scientific research is one of the cornerstones of the Global Trees Campaign. Once the baseline information is gathered, tree conservationists must develop a plan to improve the success of the interventions. The planning can prioritize individual species, like the arroyo oak or the Mulanje cedar, or larger groups of tree species present in the same area or experiencing similar threats.

In Kenya, for instance, Global Trees Campaign partners collaborated with the Kenya Forest Service and the Conservation Planning Specialist Group (part of the International Union for Conservation of Nature) to organize a series of online workshops focused on planning conservation action for Kenya’s threatened trees. The workshops brought together key stakeholders to evaluate the results of an analysis for Kenya’s more than 140 threatened tree species. This effort helped prioritize sites for conservation by grouping threatened species that are likely to benefit from the same conservation activities. During these workshops, the participants developed a joint vision statement and goals, and they identified actions at national and regional levels. The Global Trees Campaign plans to continue using this larger- scale approach in the future, maximizing efforts and often achieving more cost-effective results than approaches focused on individual species.

Comprehensive Information

Before the State of the World’s Trees was published, comprehensive information was lacking on which tree species are threatened with extinction and where conservation e orts should be directed. Some assessments were available on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species and national Red List publications. Still, the information was not easily accessible, and the scale of the problem was unknown. To produce a global overview of the conservation status of trees, the Global Trees Assessment team collated existing assessments, and each species was assigned one of six risk categories: extinct, threatened, possibly threatened, not threatened, data deficient, and not evaluated. Although this effort alone was an enormous task that took more than five years and five hundred contributors, it also revealed the information gaps regarding many tree species. In the report, well over seven thousand species were classified as data deficient, meaning there wasn’t enough information for an assessment. Moreover, assessments for many little-known tree species are often based on historic herbarium records that may misrepresent recent changes in land use or loss of populations. Further survey work is therefore required.

The information from the Global Tree Assessment can be accessed online via a public web platform, the GlobalTree Portal. The portal highlights the scale of the problem and provides information on the numbers of species found in at least one protected area (as well as species not represented in any protected areas). The portal also shows which species are present in, or absent from, ex situ collections, such as botanical gardens and seed banks. According to the GlobalTree Portal, approximately 56 percent of threatened tree species occur in at least one protected area, and 21 percent are maintained in botanic gardens or seed banks. Another online tool, Conservation Tracker, provides real-time information on who is taking conservation action for which species. These tools will be updated regularly, helping to guide ongoing conservation efforts. The idea is that on-the-ground efforts, such as Global Tree Campaign projects, will use this information and contribute new data as they evolve, creating an information feedback loop that will result in effective conservation actions.

Targeted Action

According to the Global Tree Assessment report, agriculture and logging are the leading threats to trees globally. When managed effectively, protected areas can provide vital protection against this kind of habitat loss, but in some cases, ecological constraints and threats within protected areas can still prevent or limit regeneration. For instance, even though the arroyo oak occurs within the Sierra La Laguna Biosphere Reserve, natural regeneration has been impossible due to grazing. Tree conservationists must therefore identify and remove barriers to natural regeneration, although additional interventions may be necessary for many species, such as those with extremely small populations. In such cases, planting can be an essential strategy to increase population numbers or reintroduce a species.

In the case of Magnolia grandis, with a global population totaling fewer than three hundred adult trees, targeted action was needed to ensure the future of the species. Since 2013, as part of the Global Trees Campaign, FFI has developed an outreach program with local cardamom growers at Tung Vai Watershed Protection Area in Vietnam. These efforts are paying off, with local cardamom farmers now willingly maintaining M. grandis seedlings, indicating a shift in attitudes and behavior towards this species. Over the same period, regular community monitoring and patrolling to protect trees from logging was introduced, resulting in no felling or damage to M. grandis individuals at Tung Vai since 2017. In addition, local communities have adopted fuel-efficient stoves, reducing pressure for firewood. Given the low number of individual trees in the original populations, tree conservationists are conducting booster plantings using nursery-grown seedlings. Natural regeneration of M. grandis is now occurring in other areas of the forest where previously there was none, indicating that recovery work over the last eight years has been successful.

For the Mulanje cedar (Widdringtonia whytei) from Malawi, illegal logging was so intense that it removed the natural seed source from the mountain, and increased man-made fires impeded recruitment of remaining seedlings and young trees. As part of a campaign project led by Mulanje Mountain Conservation Trust, the Forestry Research Institute of Malawi, and BGCI, staff set up eight community nurseries around Mount Mulanje with more than eighty community members who had been taught to propagate the Mulanje cedar. Over four hundred thousand seedlings were purchased from community nurseries and planted by local people, providing employment opportunities and vital income. Restoration experts from the Ecological Restoration Alliance of Botanic Gardens are also helping to improve planting practices so that more trees survive and grow better. An extensive network of firebreaks is maintained on the mountain to protect planted seedlings.

Furthermore, international trade of the Mulanje cedar was restricted when the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (a multinational agreement often known as CITES) included the cedar on its list of species that are potentially threatened with extinction. Alternative sustainable uses of cedar are being investigated that could provide additional benefits to local people. Essential oils can be produced from the tree’s wood and leaves, and researchers have investigated the components of this oil to identify commercial uses, like soaps. Communities around Mount Mulanje have planted Mulanje cedar hedges from which essential oil can be extracted, and distillation equipment and training are currently being provided. This effort offers local communities alternative incomes from the Mulanje cedar that don’t damage Mount Mulanje or its plant resources. The conservation team also planted ex situ trial plots and woodlots elsewhere in Malawi. These actions aim to ensure the planted trees on the mountain remain safe for the long term.

Whatever approach is taken to reduce threats, improve natural regeneration, or restore populations of the tree species, the full engagement and participation of local stakeholders is key to the success of all tree conservation initiatives. This ensures that the approach is appropriate to the local context, has local ownership and support, and is more likely to achieve a lasting impact.

Threatened Trees in Restoration

Trees capture carbon from the atmosphere—a fact that has drawn increasing interest given that runaway levels of carbon dioxide are a significant driver of climate change. And trees are also essential components of many habitat-restoration projects. As a result, governments and organizations around the world are investing in large-scale tree planting. These tree-planting pledges and restoration projects provide an opportunity to deliver on conservation goals by incorporating threatened species into the planting plan. However, this opportunity is often missed; many tree-planting projects focus only on exotic species or, even in the case of restoration plantings, only a small number of native species.

At Jardim Botânico Araribá, in the State of São Paulo, Brazil, a team has been working on a forest restoration project since 1987, intending to restore not only specific plant species but also the entire ecosystem. The e orts at the garden are an exemplar of how threatened species can be incorporated into a successful restoration program. The garden is situated on one of the few remaining fragments of Atlantic Forest. Despite the status of the Atlantic Forest as an important biodiversity hotspot, this forest type is recognized as one of the most degraded ecosystems on the planet. So far, the garden staff has restored about fifty acres (two-thirds of the site). Due to this restoration, headwaters that supply water to Amparo, the closest city, have reappeared. The restored forest protects the riverbanks, preventing silt build-up and protecting the river water.

The restoration plantings at Jardim Botânico Araribá feature threatened species, including the endangered brazilwood (Paubrasilia echinata) and another critically endangered species in the legume family, Chloroleucon tortum. The plants for the restoration are grown in partnership with a commercial nursery that also supplies these native tree seedlings to customers for planting in their local area. As a result, the species are becoming part of the local supply chain of native tree species in São Paulo.

Scaling Up Conservation Action

With such a vast number of trees at risk of extinction worldwide, a significant scaling up of conservation action is urgently needed. To increase effectiveness and avoid duplication of effort, tree conservationists should mobilize at national levels. It’s also crucial to coordinate efforts around specific taxonomic groups, especially genera or families with a high number of threatened species. Species within the same taxonomic group share many characteristics, and they may be subject to the same or similar threats. Therefore, related species are likely to benefit from the same conservation actions.

BGCI and the botanic garden community have established groups known as Global Conservation Consortia, which are developing comprehensive conservation strategies for highly threatened taxonomic groups identified by the Global Trees Assessment. The consortia aim to coordinate in situ and ex situ conservation e orts and disseminate species recovery knowledge. For example, the Global Conservation Consortium for Oak, led by The Morton Arboretum, mobilizes experts and local partners to conserve oaks, a culturally and economically important taxonomic group that cannot be protected in seed banks. As part of these efforts, the team has organized educational webinars, provided training on seed collection and species propagation, and coordinated regional meetings and workshops focused on filling knowledge gaps for species of conservation concern. To date, Global Conservation Consortia have been developed for six tree groups: oaks (Quercus), magnolias (Magnolia), rhododendrons (Rhododendron), maples (Acer), southern beeches (Nothofagus), and the dipterocarp family (Dipterocarpaceae). These groups include more than eight hundred threatened species, and the model is now also being applied to highly threatened non-tree groups.

National coordination of tree conservation efforts is also a valuable approach, as the collaborations in Kenya have demonstrated. The GlobalTree Portal allows tree conservationists to identify countries with high numbers of threatened tree species, especially those with high numbers of threatened endemics. These countries must be priorities for coordinated conservation. Indonesia, for instance, has almost seven hundred threatened tree species, with ongoing habitat- and species-level threats providing little chance for their recovery without dedicated conservation action. While many large-scale conservation programs are dedicated to the country’s flagship animals (such as elephants, orangutans, and tigers) or to large areas of high-carbon forest, few initiatives are specifically designed around the conservation needs of individual threatened tree species in situ.

Through the Global Trees Campaign, FFI has successfully engaged the Indonesian government in threatened tree conservation. As a first step, FFI established the Indonesian Forum for Threatened Trees, a group of more than seventy members from at least thirty different institutions. The forum convinced the Ministry of Environment and Forestry to consider adding twelve threatened tree species to their list of priority species. So far, one of these trees, a critically endangered dipterocarp known as Vatica javanica ssp. javanica has become legally designated as a National Protected Species. In 2019, the Forum for Threatened Trees and the Indonesian Institute of Sciences published a ten-year national conservation strategy for the twelve priority species. At the same time, FFI also seeks to build capacity for organizations working on threatened trees and inspire new action for priority species.

Mobilizing a Global Community

In contrast to the numerous well-known flagship animal species, threatened trees have gained little attention from governments, funders, conservation organizations, the corporate sector, and the public. With 30 percent of tree species shown to be at risk of extinction, this needs to change. Tree conservation requires a concerted response from the global community, with all different regions and sectors engaging and taking action. Botanic gardens and arboreta are in a strategic position at the intersection of research, outreach, and conservation and can play a critical role in safeguarding the world’s tree species. The urgency of the situation, however, requires an “all hands on deck” approach.

Botanic gardens and arboreta are in a strategic position at the intersection of research, outreach, and conservation.

Policymakers at all levels (global, national, and local) need to incorporate and prioritize threatened trees within legislative frameworks. Intergovernmental and international organizations need to promote and share data from the Global Tree Assessment with their networks and integrate threatened tree conservation into their programs. The corporate sector has an expanded role to play, particularly companies engaged in timber, agriculture, and extractive industries. Land managers, including governments, are key actors in securing critical habitat. Members of the conservation organizations need to prioritize threatened trees within their programs, supporting action on the ground and generating a higher profile for this issue. The tree-planting and habitat-restoration sector have an unrivaled opportunity to integrate threatened trees within their work, contributing significantly to saving species while meeting their other goals. There is a role, too, for the research community. Researchers are necessary for filling information gaps on threatened species and demonstrating the role of tree species diversity in ecosystem resilience. Moreover, there is a need for committed individuals—global citizens who advocate on behalf of threatened trees. Now is the time to act.

Further Reading:

BGCI & FFI. 2021. Securing a Future for the World’s Threatened Trees—A Global Challenge. BGCI: Richmond, UK.

Silvia Alvarez-Clare is the director of global tree conservation at The Morton Arboretum. Kristy Shaw is the head of ecological restoration and tree conservation at Botanic Gardens Conservation International. Sarah Pocock is the programme officer for plant conservation at Fauna & Flora International.