There are dead bodies buried under the cherry trees!

Motojiro Kajii, “Under the Cherry Trees” (trans. David Boyd)1

It’s true, I swear. How else could they flower that beautifully? That unbelievable beauty made me uneasy for a couple of days. But now, finally, I get it. There are dead bodies buried under the cherry trees.

I swear, it’s true.

Exposition

Snapped branches at either end of a century; a stretch of bark once elegantly carved out in ridges and dappled with lenticels, now hacked and cracked into splinters, trunk cut off at the waist to reveal the heartwood within. The cherry-red of shorn wooden vessels carrying centuries of watery memory.

This is how sakura came to me in a shadowy hour, deep in the bitter chill of winter and the crushing gravity of the pandemic, buried beneath mounds of mourning and morbidity. Amid a breakup with my thesis advisor and a breakout from the confines of a single discipline, the trees called out to me in a headline and a photograph, demanding that I pay careful attention to the stories etched into their bark and ripped into their rings. They played me a quiet symphony of multispecies memory and wisdom.

On December 8th, 1941, the day after the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor and US entry into WWII, the cherry trees of the Washington, D.C. Tidal Basin were violently broken and vandalized with the words “To Hell with the Japanese.” The trees had been given as gifts by the Japanese government thirty years prior and planted as seeds of peace. This intense anti-Japanese sentiment marked in wood would ultimately burgeon into the imprisonment of 120,000 Japanese-Americans in internment camps from 1942 to 1946.2

Eighty years later, in January of 2021, a hooded vandal appeared outside the Japanese Cultural Center in San Francisco and viciously snapped the branches of several cherry trees planted around the building.3 Though threatening in its symbolism, this event paled in comparison to the anti-Asian violence and hate crimes occurring frequently around the country at the time, a symptom of the xenophobic panic surrounding COVID-19.

With these images of hatred and violence hacked into bark, sakura revealed itself to me as a marker of geopolitical chaos translating into violent racism and xenophobia. I was called to go beyond my study of the flowering cherry at face value, called to pay close attention to the tree’s resonance through the bounds of time and species, the common threads of history bound by its branches.

Sakura (さくら/桜) is just one of many names for flowering cherry trees. I have tangled with them often along the timeline of my life. I met “sakura” first as a child, regaled with flowery dreams as my parents planned our springtime trip to D.C., only to find that we had missed their transient bloom. Next as a preteen, poring over ink drawings of a Sakura with the pink-petaled power to alter universes. As a tired teenager visiting Kyoto, walking pebble paths and staring watery-eyed at the weeping branches above—and as an adult not much older but a few lives wiser, guided by mentors and ancestors into taking the trees as my teachers, opening my roots and branches to unlikely storytelling companions.

My study of cherry trees grew from prior research on the phenology, or timing of life stages, of native and non-native plants. Using historical collections and other observational databases, I worked to understand how phenology has been impacted by the intersecting issues of climate change and species introduction, under the mentorship of plant ecologist and biological invasion specialist Sara Kuebbing. Hoping to continue investigating these questions for my senior undergraduate thesis, I took Sara’s suggestion to look into cherry trees. It was the beginning of the fall semester, 2019, when my father’s funeral hymns still echoed in my ears and the words COVID and “China virus” were faint on the horizon.

I was awestruck to find that cherry blossom flowering has been recorded in detail for over a thousand years. In an incredible dataset from Yasuyuki Aono et al., flowering times for cherry trees in Kyoto dating back to the year 800 A.D. were compiled from meteorological monitoring, imperial records, diary entries, and poetry. Their analysis revealed that in the past thirty years, the cherry blossoms have bloomed earlier than ever before in the past twelve centuries, marking the disproportionately rapid warming of anthropogenic climate change.4 The population in Washington, D.C. has also been well-recorded over the last century, revealing similar shifts to earlier flowering with warmer temperatures.5

In this way, cherry blossoms serve as a well-known and well-documented environmental indicator. With a brief, breathtaking, and bountiful bloom, they have long been the object of veneration and appreciation in cultures across the world. The ancient Japanese were some of the first to watch sakura, which they saw as the seat of the mountain deity of rice paddies and a conduit for the souls of the dead to pass from this realm.6 Through this they came to understand the trees and their flowers as markers of both seasonal and spiritual cycles, looking to the timing of cherry blossom bloom to mark the coming of spring and to forecast conditions for the autumn rice harvest and the length of winter.7 This reverence and regard for sakura remained despite the physical, social, and geopolitical transformation of their environments: hanami, or cherry blossom viewing, began as a ritual in honor of the sacred cycles of life and grew into the countless modern celebrations seen around the world today.8 The rush of millions of hopeful viewers and festivalgoers chasing falling pink petals now figures heavily into springtime tourist economies across Japan as well as in cities from Washington, D.C. to Auckland, Hamburg to Busan.9

All cherry trees flower, and even those not commonly celebrated as cherry blossoms have often been planted for their elegant flowers and the other useful qualities of their fruits, shoots, roots, and bark. Sweet cherry (P. avium) was used in ancient Southeastern Europe for food and medicine, and several species of 사쿠라나무 (sakuranamu) were used in Korean folk medicine to treat asthma, allergies, heart failure, and other ailments.10 Black cherry (P. serotina) was also used by many American Indigenous nations for food, medicine, and woodworking, including the Cherokee, Potawatomi, and Shinnecock peoples.11 The species was brought to Europe as an ornamental in the early 1600s but ultimately became of interest for timber production, widely planted for its ability to grow fast and well even on poor soils; later, however, it was noted for “aggressive invasiveness” when its popularity among seed-dispersing birds and mammals led to spontaneous spread.12 As such, cherry blossoms have appeared at places of tension and transformation among living things in diet, medicine, and ecology.

Indigenous uses of flowering cherries were typically matched with a view of the trees as spiritual intermediaries between life and death, seen in Cherokee teachings of the reciprocal relationship between humans and life-giving trees as well as in the funeral rites of early Mesolithic Europeans.13 Across three continents, cherry trees and their offerings to humans were treated with reverence, understood as markers of transformation in life at the level of cells and organs as well as in multispecies relationships. In the many societies where they appear, these trees have imparted healing and nourishment as well as wisdom about the turning of the universe.

Sakura have watched over us for centuries, grown through the birth and death of peoples, places, and powers. These exceptional plants have long shaped and symbolized the way that people view and interact with their world, and as they adapt in meaning, they tell an intricate story of how relationships among humans and nonhumans have shifted over time and space. Their symphonic record of transformation and renewal includes the capture of growth, destruction, and chaos in rich multispecies environments.

It doesn’t matter what kind of tree it is. When its flowers are in full bloom, the air is infused with a sort of mystic energy. It’s like the perfect stillness of a well-spun top, of the trance state that comes with any virtuoso concert—a hallucinatory halo of feverish reproduction. It’s a strange, vital beauty that never fails to pierce the heart.

“Under the Cherry Trees”

Development

The storylines surrounding the introduction of species to new regions of the world are as twisted and tangled as their paths overseas. For decades, the appropriate classification and treatment of species known as non-native, introduced, or invasive has been hotly debated among scientists, legislators, and even gardeners. The movement of plants between regions has often involved multiple actors and intentions, garnering many different attitudes—much like the migrations of humans.

Black cherry was not the only Prunus species to experience shifts in both environment and public opinion. Sweet cherry was carried by colonists from Europe to North America around the same time, alongside sister species tart cherry (P. cerasus), both of which would be planted in gardens, farms, and roadsides until shifting into widespread commercial fruit production in the late 1800s.14 Though cultivated throughout the northeastern colonies and later brought to the west in another wave of colonization, this “wild cherry” is now condemned as an invasive threat in the United States.15 Like other plants listed as “noxious,” broadly defined as “competitive, persistent, and pernicious,” sweet cherry is said to displace native species with similar habitats and to serve as a host for pests and diseases.16

Wild and native; noxious and pernicious—terms used to describe plants and their habitats come bearing moral and political meaning. Encountering the biology of introduction and migration in coursework, I already knew how laden these questions were, and how they cried out to be contested. I knew that the ecosystem in the era of early botanists and collectors, concurrent with the oppression and brutalization of Native peoples, could not reasonably be called a “native assemblage,” much less a pristine biome, free from human influence. I knew that the meanings of “native” and “non-native” were not strictly scientific, but rather made and constructed by the holders of land, power, and knowledge. We might better term this system a biology of transition and consequence—an environment in an unprecedented state of flux after rapid colonization. These ecologies were defined by the disruption of an intricate web of relations once maintained by Native peoples, a kind of stewardship suppressed but not silenced by colonial violence. It was a dynamic system such as this into which sweet cherry was planted and from which black cherry was taken.

These invasive species shared something deeply woven into my history, perhaps even my blood and body, threaded together by our paths between lands.

Yet these nuances were conspicuously absent from conversation in class, with no mention of this blurring of lines in the histories and language of introduction. My feelings of discomfort blossomed into latent rage as I sat in a discussion section and listened to my exclusively white classmates, led by our white, male professor, carelessly toy with the fraught politics of invasive species. I could only wince as I imagined how their ruthless words about non-natives might sound if “plant” were replaced with “person.” When I finally spoke up, decrying the xenophobic narratives and violent language surrounding the early movement against invasive plants and animals, I found I was fighting back furious tears.

Was my own life not defined by the experiences of myself, my family, and my people, who too have been intermittently treated as exotic prize and invasive pest in this land of promise? Was I not as foreign as any tree of heaven or Chinese tallow tree seeded and grown here in America? Perhaps the brutal methodologies of control and suppression, varnished as they were with the academic jargon of a science said to be about preserving life, reminded me just a little too much of an immigration tirade online—or even a mid-20th century wartime call to blanket Asian landscapes with fire and toxin, or the longer and more insidious history of forcible sterilization of Black, Brown, and Indigenous people. My white American peers, these kids whose ancestors came with the same rags but rose to different riches, couldn’t seem to understand how the early invaders who desecrated the land and its stewards alike had also written up rules for what kinds of life would be permitted in a blossoming country. Those rules never really changed—only the words.

With this language of invasive species plucking at my own bloodline, I could not help but feel disconcerted by the casual demonization of non-natives. Could no one else hear these chords struck with the dissonance of a rewritten history? Could no one else hear the resonance of these migration stories with those of people like my own family? These invasive species shared something deeply woven into my history, perhaps even my blood and body, threaded together by our paths between lands. I could understand wanting to preserve the native ecology, but it was clear that definitions of native status were deeply impacted by human relations to the landscape at the time of cataloguing, something that had shifted radically as plants and peoples alike moved into it. “Well, I had invasive trees in my hometown growing up, and I really liked them,” said my professor. “I don’t think it’s a racist thing.” I would have laughed bitterly if I’d had the breath. How many white men like him would readily deploy this sentiment, denying underlying racism with the defense that they know and maybe even like a person of color? I’d heard it just weeks before, confronting a young man who called me a racist slur and then proceeded to argue that he couldn’t possibly be racist because he dated a Korean girl once. Thinking of that all-too-familiar dismissal, the taste of bile rose into my throat once more. I swallowed it. It tore its way through to the core of me. The application for my research grant was still pending. This professor was influential, and I had been encouraged to seek out his advisory approval. He was an expert in his field, a science bigshot, and I was just some tree-hugging Asian kid with a sensitivity for social justice who had somehow turned up in his ivory tower. Feeling more than ever that I was not native to this land, I sank quietly into hopelessness.

That discussion section made it uncomfortably clear to me that the problem of species introduction, like that of climate change, could not be studied in isolation as an issue of non-human ecology. This was not just a conservation movement, but a political force colored by race-based hate, embedded in a network of physical and sociocultural environments. The migration of species between lands was also the migration of species between nations, peoples, and systems of power.

My understandings of these worldly things—movements, environments, networks of people and power—would radically shift over the following months, as the world was rent apart by turmoil, death, and mourning, from the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, through the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and too many more, to the storming of the Capitol Building.

During this time, I peered a bit deeper into the history of my trees, wondering what detail might be hidden beneath the surface of sakura’s introduction to the United States. As it turned out, the language of invasive species discourse, which had so strongly reminded me of anti-immigrant hate speech, was born alongside legislation like the Chinese Exclusion Act and the Asian Exclusion Act, regulations wrought with racism and xenophobic panic following the influx of Asian laborers in the early American industrial age.17 And while the sakura of D.C.’s Tidal Basin were intended as a gift of peace from an East Asian nation—an offering of soft, pink-petaled Asian femininity to offset the foreign masculinity of immigrant miners and railworkers—the first shipments of trees were burned in massive bonfires to eradicate stowaway pests like scale and root gall.18

After their planting, public opinion of Washington, D.C.’s cherry trees shifted periodically. Women were integral to the continued presence and growth of these sakura—from the initial vision and passion of Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore; to the orchestration of the gift through First Lady Helen Herron Taft and Viscountess Chinda, wife of the Japanese ambassador; to the later protection of the trees from uprooting by women like Eleanor “Cissy” Patterson, who chained themselves to the trunks during the Cherry Tree Rebellion of 1938.19 Despite avoiding transplantation for a slaveowner’s memorial at this time, the trees were not able to evade the violence of war over the next decade, becoming an outlet for racially charged fear, rage, and hysteria. In peacetime, the cherry blossoms would again become adored for their hopeful symbolism and celebration of multicultural community.

By the 1970s these cherries were facing disease, damage, and decay, persisting only with the care of Roland Jefferson, first African-American botanist at the United States National Arboretum. Noticing the cherry trees in decline, Jefferson propagated over one hundred trees from cuttings of the original gifts, effectively preserving the collection. Many of these cuttings were given back to Japan, part of Jefferson’s ongoing efforts for the exchange of plants, which would later include a collecting trip and a program trading cherry seeds for American dogwood.20

With sakura’s buds brushing at the edge of my awareness, I could not help but see the migration stories of my flowering cherry species in a new light. I saw the sweet cherry tree, carried across the sea to make fruit for the colonists who brought death, disease, and disruption; I saw my mom step out onto the tarmac in New York City with a hundred dollars in her pocket, Chinese hands poised with Filipino training to save American lives. I saw black cherry, sought out for its efficient work but denounced as aggressive invader when it made new roots and branches; I saw my mom lauded as the pinnacle of the American Dream and just as soon disrespected by the white men who refused her a seat at the table and a slice of the pie. I saw somei-yoshino and kanzan carrying the hope of women, immigrants, and minorities on their branches, and I felt the weight of my mother’s dreams built into my own aching shoulders.

These parallel histories of plants and people took the forefront of my independent study presentation that winter. My data seemed to demonstrate different responses to temperature and precipitation in different regions, but statistics aside, something about the interpretation just felt lacking. In my eyes, the trees must be reacting to more than climate and continent alone, because it was their multispecies interactions that really determined how they were moved, planted, observed, and recorded. I was looking for a countermelody between those sloping lines, making narrative of what might otherwise be background noise in the question of how flowering cherry trees responded to the environment. It didn’t quite occur to me that my new approach might not be considered a valid way of answering this question.

My advisor was quiet for the duration of my presentation. At the end, he gave me an incomplete grade and asked that I spend the winter break gathering my materials to show that I had done a semester’s worth of rigorous scientific work.

Roots cradle the bodies like gluttonous octopuses; tangles of root hairs, like sea anemone tangles, suck up the fluid. What makes those petals? What makes those pistils? I can almost see the silent ascent of crystal liquid coursing dreamily through those veins.

“Under the Cherry Trees”

Cadenza

In that moment I was once again an invasive species, stubbornly seeded among the hedges, scraggly and out of place no matter how well I grew. I felt the noxious spray of his disapproval wither my leaves and shrivel my stems. I saw my body torn and trampled, poisoned and burned, cracked and hacked away.

I was horrified and offended that he thought I hadn’t done the work—couldn’t he see that I was onto something, desperately digging to unearth a deeper story, fighting to find the words for the narrative underlying the data? I felt so sure of the power of those connections just beginning to weave themselves together, so certain that something was emerging from my obstinate attention to the cultural significance of this indicator plant. There was a reason I sacrificed half of my presentation time talking about history and hanami, neglecting to dive into the data I had in fact collected. I just couldn’t name it yet.

I stared at the outline of sakura on my screen and saw nothing but shadow. Here was a map of how my four flowering cherry species spread across the globe, a set of graphs showing how each population shifted its flowering over time and with increasing temperature—a rhythm straining to rise out of the mess of metadata and code I’d compiled—yet those rigid lines and fat dots failed to capture the interwoven histories of moving plants and humans. I turned to my browser and did a basic Google search for cherry blossoms, grasping wildly for new ideas. And that’s when sakura snared me with a headline and a jagged stump of cherrywood flesh: I see you, it said, in the language of anguished splinters beige and red. Me too.

Sakura and I shared in a kind of pain that traversed time, worlds, and species, bubbling up in bloody storylines bound and tangled together—bloodlines, resonating with more-than-human memory. It reverberated from those Japanese cherry branches in California to my Filipino-Chinese guts in Rhode Island, to the European sweet cherry called a weed in Maryland, back half a century to the mutilated sakura on the D.C. Tidal Basin. The same traumas that threaded back through generations of my ancestors also ran between organisms and their own histories, bloody storylines bound and tangled together—bloodlines. Just as sakura was desecrated in reflection of violent racism, my own body was ravaged with an unspeakable agony back then in that classroom, and now again at my computer in indication of those same undercurrents. Just as sakura strained to move and shift with a spiraling climate and an unwelcoming new home, I struggled to contend with my fear in the face of the same oppression. And just as sakura blossomed to reveal the bloodstained history seeping up from its roots, I too blushed with defiance as I leaned into the strong, ancient bark of this new flowering ancestor.

Why the pained look on your face? It’s a beautiful vision! Now I can finally train my eyes on those flowers. I’m free of the supernatural force that has been haunting me.

Under the Cherry Trees”

Refrain

It was simple enough to compile the data that proved my efforts at scientific inquiry, resolving my grade for the semester. I followed up by notifying my professor that I would be shifting to a new advisor for the remainder of my thesis work, investigating the intersections of environmental and social change I saw in sakura’s multispecies entanglement. Environmental historian Bathsheba Demuth is best known for her work telling transformative stories of change, consequence, and contingency in Beringia; with the power to find the judgements of whales in archived ship logs and sailors’ diaries, she is well-versed in the art of paying attention to ripples under the surface.21 With the urging of Bathsheba and sakura itself, I finally knew the question at the core of my work: the question of cherry blossoms as indicators of more than the physical—of environments human and non-human and more-than-human, social and cultural and political, natural and artificial and ecological. I would weave something new with these stories, drawing on the threads of Donna Haraway’s tangled more-than-human string figures; of Suzanne Simard’s mycorrhizal knowledge networks; of Anna Tsing’s polyphonic arts of living and dying; of Alexis Pauline Gumbs’ love for all kinds of watery kin.22

I began with the cherry blossom phenology data I had so painstakingly collected, drawing from scientific repositories as well as other archives just beginning to prove themselves useful for scientific study. Gathered into one laptop-slaying dataset was flowering information from phenology databases and occurrence records, meteorological and parks services logs, and previous studies like the Aono et al. work, as well as data I had collected myself by visually assessing images from digitized herbarium specimens and community science observations. This time I would use the statistical power I had assembled to ask the kinds of questions that could make these endless grids of numbers into multispecies storylines.

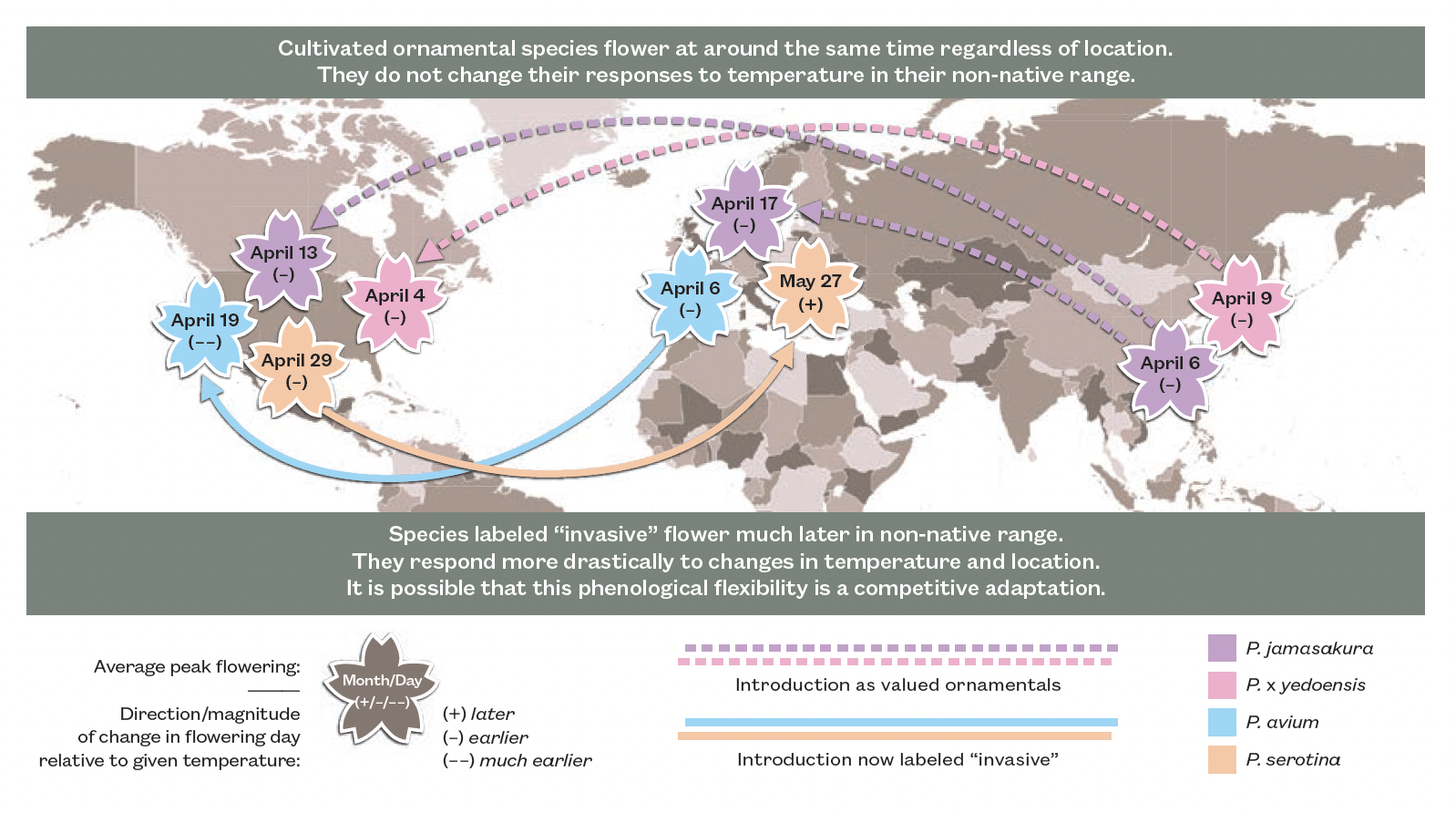

Considering each species’ history of global introduction as well as changes in temperature and precipitation, I determined that cherry blossom flowering shifted in response to both climate change and migration. Each of the four species reacted to climate as expected in their native ranges, flowering earlier with rising temperatures, and these effects were altered predictably in new landscapes. On every continent where they appear, these cherries were accelerating flowering by as much as 3.5 days per ºC, a conservative estimate relative to other findings but still corresponding to a 2-week advancement by 2050; such shifts could be enough to trigger ecological and physiological constraints posed by earlier timing relative to frost dates and the life cycles of pollinators and dispersers.

Armed with new understandings of how my study species have interacted with humans and nonhumans over time, I saw how the crisscrossing lines of model results over seas of dotted observations might also reflect the paths of shipments and immigrants across oceans. I found that differences in this flowering response corresponded to differences in the non-native classifications of each species, pointing to flowering as a potential indicator of this status. The two species considered invasive showed great sensitivity in both flowering day and climate response when introduced to new environments, reacting to temperature, precipitation, and location, while the two prized and carefully cultivated as valuable ornamentals had significantly reduced responses. I could imagine that phenological plasticity—the capacity to shift with changes in the environment—would be found in species able to form naturalized populations unassisted, an ability that might be lost if a species were to come to rely on humans for cultivation. As such, phenological plasticity is a potential adaptation that could indicate how a cherry tree species was received in its human environment. When I asked the questions shown to me through sakura’s bloom, those charts, which had once felt so empty and inconclusive, could finally tell their stories, tales of rich interspecies relationships shaped by the agencies of both humans and trees.

Reading between the lines of my scientific analysis and the history drawn up for me in vandalized bark, I could finally see that the shape of the question you asked was determined by the framing; that the weight of the histories rested on how deep into the archives you dug; that what you saw in the sakura depended on your lens. I realized that the stories sakura told through these databases and archives were only possible because they have watched over our more-than-human worlds through geologic time. They were in tune with a larger symphonic whole, responsive not just to warming climate, but to the ebbs and flows of more-than-human power dynamics. By watching the sakura in careful, thoughtful new ways, inspired by their own practice, I learned how to look more effectively. Sakura and I became storytellers together through this relationship of reciprocal regard and response.

What I found was that through history, more and more came to watch the flowering of these trees as they inhabited new symbolic spaces—in the nationalist sentiments of feudal lords and fighter pilots, in the subtle subversions of gender-bending geishas and pink petal pageant princesses, in the bitter violence of war and colonization. Through the unprecedented forms of movement and change created by modern globalization, sakura was brought into new and distinct encounters with humans, deeply entangled relationships, which reflect underlying shifts in social structures, geopolitical systems, and multicultural relations. These trees traveled the same paths as people and watched histories unfold from all over the globe.

These trees traveled the same paths as people and watched histories unfold from all over the globe.

In their transience and transformation, cherry blossoms have intermittently been emblematic of war and peace, colonization and freedom, normativity and subversion, and racism and multiculturalism. For example, sakura became strongly associated with Japanese identity partially as an attempt by Japanese aristocrats to distinguish themselves from the Chinese colonial elite, who gave high regard to the plum blossom.23 But while the ancient spiritual understanding of cherry blossoms lent itself to symbolism of the Japanese soul, the flowers also took on connotations of military power and political nationalism.24 During the brutal occupation of Korea as well as parts of China, plantings of Japanese cherry tree varieties served as a marker of colonial rule and cultural domination via the landscape.25 Later, in the transformative global turmoil of WWII, the Japanese military would weaponize the aesthetics and sentiments of sakura in their calls for tokkotai pilots (often called kamikaze) to plummet to a fiery death for their nation and emperor, bodies scattered like falling petals and souls reborn in the springtime bloom.26

With these new understandings of the cherry blossom’s story fresh at heart, I saw something bloom up through the data again, this time in an analysis of P. × yedoensis temperature responses by country. Noticing that the species exhibited a significantly reduced response to climate in Korea compared to Japan, China, and the United States, I found a paper by Myong-Suk Cho et al. that detailed controversies over the tree’s origin and presence in Korea. While P. × yedoensis was planted by the Japanese during the colonial occupation of Korea in 1910–1945, these scientists used molecular evidence to differentiate the disputed hybrid from the morphologically similar variety classified as P. yedoensis var. nudiflora which grows natively on Jeju Island.27 It is possible that their differences appear not only in genetic markers but in their phenological plasticity relative to shifts in environment, obscured by the single Latin name with which the phenology data was originally recorded.

Composing stories through my carefully collected data, the sakura taught me here to look deep into the names and classifications given to them by people around the world. The controversy over P. yedoensis and P. × yedoensis was just one hitch in a broader movement to categorize all life into a single taxonomy, a language of the powerful, in which the nuances of local knowledge and experience in naming became lost or obscured. The work of reclassifying and gathering plants, like that of the Arnold Arboretum’s own famous collectors, has brought us the joy of appreciating these trees in our nearby landscapes but also served to muddle the narratives of how people have interacted with them over time. It was the distinctions in flowering times within this generic classification that indicated to me the presence of an important underlying thread.

With this in mind, I looked beneath the Latin to sakura’s many names. To its hundreds of variants in Japanese, where subvarieties unnamed in English are given the individuality of a species, like the ukon (“turmeric”) with its curry-colored flowers and the fugenzou (“Fugen Bosatsu elephant”) with its large, pale blossoms holding pistils like bodhisattvas on their backs. To the dozens of names in the hundreds of languages of American Indigenous peoples, made not for the “species” but for the ways people interact with fruits, flowers, roots, and bark—like the Gitxsan word eluuts’ook’ (“makes your mouth smooth so nothing can slip on it”) or the Upriver Halkomelem łəәxw łəә´xw (“spit out many times”), or the Okanagan words for related varieties like sk’eluʔsáłq (“old spring salmon fruit”), stepłxiyáłnexw (“covered away from the sun”), and nts’ew’ts’ag’w-wísxn (“tasteless”).28 To the handful of cherry trees named in English, words like “bird,” “mountain,” “wild,” and even “oriental” speak of much more than the trees themselves. As I learned, flowering is just one of the many ways in which these exceptional trees reveal their responses to changing more-than-human environments over time and space.

There are myriad ways that a human can view a cherry blossom and a cherry blossom can view a human; how much more possibility do we unravel when we imagine the narratives of a pollinating insect, a dispersing bird, an herbivorous mammal, a fungal decomposer? Sakura invite us to question the view from our place in the more-than-human environment. They teach us new ways of confronting sticky entanglements of the natural and cultural, guide us into new imaginaries for knowing and learning across disciplines, pull us into new perspectives as these intersectional environmental issues demand. Taking trees and other human and nonhuman familiars as our unlikely teachers, we can grow into the rhythm and harmony of symphonic multispecies being.

Yes, dead bodies are buried under the cherry trees! Dead bodies. I have no idea where the idea came from, but they’ve become one with the trees now. No matter how hard I try to shake this fantasy from my head, it just won’t let me go.

“Under the Cherry Trees”

Coda

I remain a devoted student of the sakura. In watching them with thoughtfulness and care, taking them as storytellers, teachers, and keepers of memory, I am guided into new understandings of the powerful transformation within our more-than-human environments. Beneath the pink-petaled splendor of their branches, I will always find new strings to follow among the knots and tangles of shared history.

Inside the Arboretum’s greenhouses at Weld Hill, I spend the hours nurturing phlox—American wildflowers quick to grow big and bushy, spewing clouds of vivid yellow pollen. My body reacts to them with the need to expel and escape, eyes watering and chest heaving with sneezes, a physical rejection of the greedy enormity we coax into their flowers with canned fertilizer and electric lights. Perhaps the phlox reject me too, as do their Texan overlords, like the man who talked very casually about shooting me and my companions while we collected seeds on the roadside just outside his fence.

Perhaps the building rejects me, too—and so I felt that first spring, throat and fists and gut clenched tight as I walked through the halls and stared. Stared up into the eyes of the nameless Asian individuals who once helped a collector bring flora into our Massachusetts landscape, whose faces outnumber the Asian personnel who see them. Stared at the labels beside each photograph and willed them to give me more than the careful Latin of a plant’s binomial and the bolded English of the collector’s name. Stared at a Taiwanese cycad in a pot just below, captured and kept in plastic to pretty our hallways, just like the image of the woman labeled “peasant girl.” Stared determinedly past the longtime employee who, after several months of working in the same building as me, mistook me for an Asian caterer who looked nothing like me.

Many of those drizzly days, I found myself floating out of the building and up the slope where the oaks grow tall. Across the street and through the Walter St. Gate, down a shadowy tunnel made by the canopy of yew. Past the Bussey St. Gate, a memorial to a man who made his wealth trading the products of slavery, flanked by sandwich boards showing off the smile-stretched, light-skinned faces of the Arboretum’s employees. My feet carried me further, up the Beech Path that cuts across Bussey Hill. In early spring the dewy grass becomes blanketed with electric blue patches of Lucile’s glory-of-the-snow and Siberian squill, both non-natives and harbingers of spring, both with tangled histories of naming, much like sakura. I rushed past the Stewartia, feeling sympathy for their story—some of these ornamentals hail from East and Southeast Asia like my family, while others are from North America like me. Finally, I reached the corner of the Rosaceous Collection that includes the cherry trees and bent over a low-hanging branch in relief. I found kin in my favorite weeping Higan cherries—whose branches are often grafted onto straighter trunks because of their bent and gnarled backs—trees who know that, after reaching high into the sky, we shouldn’t forget to dive deep. The first day I visited, there were only buds. The third day, I hunted until I found one poking out a petal. A few more days saw a single flower, and then another, and then another, and in a few more turns of the earth we were approaching full bloom. The petals floated gently on the air alongside me, soft and delicate, subtly pink and just a tiny bit sweet on the air. With some distance between myself and those echoing halls, wrapped in whispering branches, I finally felt a bit of peace in my breath and blood. By visiting the sakura, and watching other plants on my path the way they taught me to do, I came to understand these resonant tensions in my own body and in the construction of Asianness in my work environment. They showed me how to use myself as an indicator of disharmony, of dissonance, and how to draw out the stories that could bring humans and nonhumans around me into polyphony again.

Soon, the photographs in Weld Hill will bear new labels, telling the story of how the Chinese, Japanese, and Korean people pictured were integral to a collaborative endeavor in plant collection that brought us not just these images, but many of the plants that compose our vast and diverse landscape. They will explain why the white men in charge of these expeditions, as in many others, did not bother to document the local people’s names, contributions, or relationships to the land. And change is underway—already, there is at least one more live Asian face in the hallway smiling at me. When my body takes me across the landscape, up the hill, and through those fields of blue, I see that the Stewartia are listed as natsutsubaki (ナツツバキ) and nogaknamu (노각나무)—“summer camellia” and “overripe cucumber tree,” names telling stories that tickle rather than burn my throat. I greet the sakura head held high.

If I bothered to pull up the code each spring, my model could predict for me when the cherry trees would be in peak flower anywhere in the world that season, give or take a couple days. But I find that I learn much more about the turning of my world when I watch the plants and let them tell me instead.

At last, I feel as if I have the right to gaze up at the flowers and enjoy a drink like the people reveling over there, under the cherry trees …

“Under the Cherry Trees”

Izzy Acevedo is a research technician at the Arnold Arboretum and winner of the 2021 prize for Best Thesis in Environmental Science at Brown University. This work was conducted through the Voss fellowship and the GCA Award for Summer Environmental Studies.

Endnotes

- Motojiro Kajii, “Under the Cherry Trees.” Translated by David Boyd. Monkey Business vol 5 (2018). Excerpts appear by permission of the translator.

- “The Vandalization of the Cherry Trees in 1941,” National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, https:// www.nps.gov/articles/the-vandalization-of-the-cherrytrees-in-1941.htm.

- Allyson Waller, “Cherry Blossom Trees Vandalized in San Francisco’s Japantown,” The New York Times (2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/08/us/japantown- cherry-blossom-trees.html. Also note this story from 2015, in which four full-grown flowering cherry trees were hacked down in Birmingham, UK, an incident passed off as “mindless” vandalism: “Cannon Hill Park Cherry Trees Attacked in Act of Vandalism,” BBC News (2015), https:// www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-birmingham-32629055.

- Yasuyuki Aono and Keiko Kazui, “Phenological Data Series of Cherry Tree Flowering in Kyoto, Japan, and Its Application to Reconstruction of Springtime Temperatures since the 9th Century,” International Journal of Climatology 28, no. 7 (2008); Yasuyuki Aono, “Cherry Blossom Phenological Data since the Seventeenth Century for Edo (Tokyo), Japan, and Their Application to Estimation of March Temperatures,” International Journal of Biometeorology 59, no. 4 (2015).

- Uran Chung et al., “Predicting the Timing of Cherry Blossoms in Washington, Dc and Mid-Atlantic States in Response to Climate Change,” PLoS One 6, no. 11 (2011).; Mones S Abu-Asab et al., “Earlier Plant Flowering in Spring as a Response to Global Warming in the Washington, Dc, Area,” Biodiversity & Conservation 10, no. 4 (2001).

- Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney, Flowers That Kill: Communicative Opacity in Political Spaces (Stanford University Press, 2015).

- Ohnuki-Tierney, Emiko. Kamikaze, Cherry Blossoms, and Nationalisms: The Militarization of Aesthetics in Japanese History (University of Chicago Press, 2002).

- “Cherry Blossoms and Their Viewing,” In Sepp Linhart and Sabine Frühstück, eds., The Culture of Japan as Seen Through its Leisure (Albany: SUNY Press, 1998).

- Chloe Whiteaker, Katanuma, Marika, and Murray, Paul, “The Big Business of Japan’s Cherry Blossoms,” Bloomberg, https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/ 2019-cherry-blossoms/; Horus Alas, “National Cherry Blossom Festival Generates over $100 Million for DC,” Capital News Service, https://cnsmaryland.org/2019/05/01/ national-cherry-blossom-festival-generates-over-100- million-for-dc/.

- Zahida Ademović et al., “Phenolic Compounds, Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Properties of the Wild Cherry (Prunus Avium L.) Stem,” Acta Periodica Technologica, no. 48 (2017); Erdem Yeşilada et al., “Traditional Medicine in Turkey Iv. Folk Medicine in the Mediterranean Subdivision,” Journal of ethnopharmacology 39, no. 1 (1993); YQ Zhang et al., “The Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Cherry Blossom Extract (Prunus yedoensis) Used in Soothing Skincare Product,” International journal of cosmetic science 36, no. 6 (2014); Jin-Ho Lee et al., “Wound Healing Effects of Prunus Yedoensis Matsumura Bark in Scalded Rats,” Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2017 (2017); Hong-Sun Yook et al., “Antioxidative and Antiviral Properties of Flowering Cherry Fruits (Prunus Serrulata L. Var. Spontanea),” The American Journal of Chinese Medicine 38, no. 05 (2010).

- Daniel Moerman, “A Database of Foods, Drugs, Dyes and Fibers of Native American Peoples, Derived from Plants,” (Native American Ethnobotany Database, 2003).

- U Starfinger, “Introduction and Naturalization of Prunus serotina in Central Europe,” (1997).

- Barbara R. Duncan and Davey Arch, Living Stories of the Cherokee (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1998), Book, 128–29; Dragana Filipović et al., “Gathered Fruits as Grave Goods? Cornelian Cherry Remains from a Mesolithic Grave at the Site of Vlasac, Danube Gorges, South-East Europe,” Quaternary International 541 (2020).

- Miklos Faust and Dezsd Suranyi, “Origin and Dissemination of Cherry,” Horticultural Reviews vol. 19, 1997.

- “The Cherry Blossoms Have Arrived! Some Good, Some Bad.,” Maryland Invasive Species Council.

- Ibid.; “About Weeds and Invasive Species,” U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, https://www.blm.gov/programs/natural-resources/ weeds-and-invasives/about.

- Philip J. Pauly, “The Beauty and Menace of the Japanese Cherry Trees: Conflicting Visions of American Ecological Independence,” Isis 87, no. 1 (1996): 51–54.

- Ibid., 70–72.

- “History of the Cherry Trees,” National Park Service; “The Cherry Tree Rebellion,” National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, https://www.nps.gov/articles/ the-cherry-tree-rebellion.htm.

- “Roland Maurice Jefferson Collection,” U.S. Department of Agriculture, https://www.nal.usda.gov/collections/ special-collections/roland-maurice-jefferson-collection; “Cherry Blossoms—Restoring a National Treasure,” AgResearch Magazine 1999.

- Bathsheba Demuth, Floating Coast: An Environmental History of the Bering Strait (W. W. Norton & Company, 2019).

- Under Professor Demuth’s mentorship, I began to explore the rich scholarship on more-than-human worlds, guided by works like the following: Donna J. Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Duke University Press, 2016); Suzanne W. Simard, “Mycorrhizal Networks Facilitate Tree Communication, Learning, and Memory,” in Memory and Learning in Plants (Springer, 2018); Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton University Press, 2015); A.P. Gumbs and adrienne maree brown, Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals (AK Press, 2020).

- Ohnuki-Tierney, Kamikaze, 33–34.

- Ibid., 116–18.

- Hai Gyoung Kim, “A Study on Interpreting People’s Enjoyment under Cherry Blossom in Modern Times,” Journal of the Korean Institute of Traditional Landscape Architecture 29, no. 4 (2011): 124; Ohnuki-Tierney, Kamikaze, 122–23.

- Kamikaze, Cherry Blossoms, and Nationalisms: The Militarization of Aesthetics in Japanese History, 116–18.

- Myong-Suk Cho et al., “Molecular and Morphological Data Reveal Hybrid Origin of Wild Prunus Yedoensis (Rosaceae) from Jeju Island, Korea: Implications for the Origin of the Flowering Cherry,” American Journal of Botany 101, no. 11 (2014).

- Nancy Turner, “Appendix 2b. Names of Native Plant Species in Indigenous Languages of Northwestern North America,” in Ancient Pathways, Ancestral Knowledge: Ethnobotany and Ecological Wisdom of Indigenous Peoples of Northwestern North America (McGill-Queen’s PressMQUP, 2014).