On a visit to Kunming in 1984, Dr. Peter S. Ashton, then director of the Arboretum, happened to meet Professor Hsueh of the Southwestern Forestry College and suggested that he write a short memoir of his early involvement with Metasequoia glyptostroboides. The article, originally published in Arnoldia in 1985, is included here for its sharp, very fresh sense of excitement about the discovery; no anthology devoted to Metasequoia glyptostroboides would be complete without it.

Forty years ago [1945], I happened to see the specimen of Metasequoia glyptostroboides that Mr. Wang Zhang had collected at Modaoqi village in Wanxian county, China. The next year, following the route Mr. Wang had taken, I made two trips there to collect perfect specimens and to conduct further investigations. Although I am old now, the two trips are still fresh in my memory.

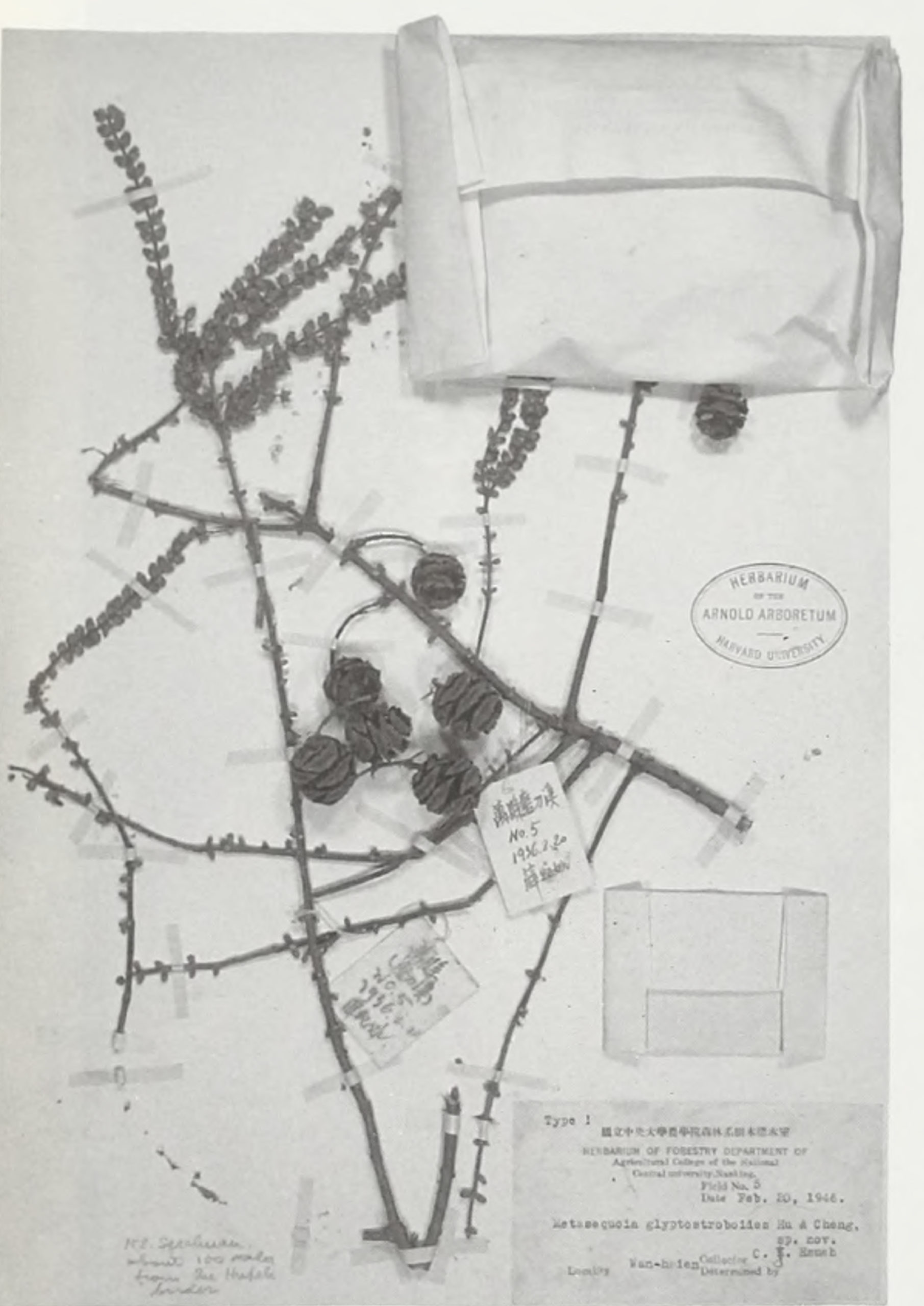

I graduated from the Forestry Department of the former National Central University at Zhongjing (Chungking) in 1945 and then worked on the gymnosperms, studying for a master’s degree under the guidance of Professor Cheng Wanjun. One day in 1945, Wang Zhang, who worked at the Central Forestry Experimental Institution, sent a cone-bearing specimen collected at Modaoqi to Professor Cheng for identification. Its vernacular name was shui-shan (water fir), and it was somewhat similar to Glyptostrobus pensilis (G. lineatus). After making a preliminary identification, Professor Cheng considered that it might belong to a new taxon of the Gymnospermae, since the opposite arrangement of the leaves and cone scales differed from that of G. pensilis and other members of the Taxodiaceae.

Since the specimen Mr. Wang collected had no male inflorescences and since the cones had been picked up from the ground, we didn’t know how the cones grew on the branches. In addition, we had no information on whether it was deciduous or evergreen, on its flowering season, or on its ecological characteristics and distribution.

Further research being necessary, Professor Cheng naturally advised me to collect some perfect specimens and to make an investigation. Since we had no funds and everybody was quite hard up, I could only go to the place on my own, carrying a few pieces of simple baggage and specimen-clips. I left Chungking city by steamboat and, after two days, arrived at Wanxian county, on the northern bank of the Changjiang (Yangtze) River. After crossing the river, I had to walk 120 kilometers [72 miles] to my destination. In 1946 I made two trips from Chungking to Modaoqi, in February and May, respectively, both times singlehandedly.

The First Trip to Modaoqi

I remember that on my first trip the boat was moored in Fengdu county for the first night. On a hill behind the county town was a temple regarded in the Old China as an inferno where the “Lord of Hell” reigned. Dead souls were supposed to go there to register. So I made use of this rare opportunity to take a solitary night walk in this weird and dreadful place—evidence that I was full of vigor and curiosity in my youth.

At that time there was no highway from Wanxian county to Modaoqi village. My trip was very difficult, the trails threading through the mountains being less than one foot wide. The region was inhabited by the Tu minority and had been isolated from the outside world for ages. During the war of resistance against Japan, the Hubei provincial government moved to Enshi county in its neighborhood; thenceforward its intercourse with the outside world had somewhat increased. Since this region was located on the border between Sichuan and Hubei provinces, an area characterized by difficult and hazardous roads, murder and robbery occurred frequently. It was regarded as a forbidding place and was seldom visited by travelers.

On my trip, I set out from Wanxian and stayed at Changtanjing for the night. My fellow travelers were several peddlers. While we chatted around a fire at night, the innkeeper came to give us a warning: “If you go any farther you will travel along a narrow valley cut by the Modaoqi River. Travel will become more dangerous and threatened with robbery, which often occurs at dangerous turns of the river. Travelers from both directions are robbed by being jammed together, or ’rounded up.’ Therefore, if you see no travelers coming your way for a long time, it is very likely that a robbery has occurred ahead, and you had better take care. Only a few days ago we witnessed such an incident in this vicinity.” The innkeeper then gave a vivid and horrible description of a murder. The poor peddlers, my fellow travelers, were very frightened. They dared not go any farther and returned to Wanxian the next morning. As for me, I was bent on finding that colossal tree and collecting more specimens, so I resolutely continued my trip along the route marked out by Mr. Wang, without any fear or hesitation.

Finally, at dusk on the third day, I reached my destination safely. I set out immediately to search for that colossal tree despite hunger, thirst, and fatigue, and without considering where I would take my lodging. It was February 19th and cold. The tree was located at the edge of the southern end of a small street. In the twilight nothing was discernible except the withered and yellowed appearance of the whole tree. My excitement cooled.

“Am I to bring back just some dried branches?” I asked myself.

The tree was gigantic; no one could have climbed it. As I had no specific tools, I could only throw stones at it. When the branches fell from the tree, I found, to my great surprise, that there were many yellow male cones and some female cones on the leafless branches. I jumped with joy and excitement. The weather being cold, many plants were not yet in flower. Since I was short of money, I returned to Chungking city three days later.

The Second Trip to Modaoqi

The second trip was in May of the same year, its purpose being to collect the cone-bearing specimens in addition to ascertaining the natural distribution of Metasequoia and the flora of the region. On my way to Modaoqi, about half a day’s walk from my destination, I came across a peasant carrying a fagot mixed with some Podocarpus nagi. The wood was said to have been cut from a nearby mountain. I took two twigs and pressed them as specimens. This indicated that P. nagi, another primeval gymnosperm, occurred in the vicinity.

This time I took measurements of the Metasequoia tree. It was 37 meters (about 122 feet) high and 7 meters (about 23 feet) in girth, and still grew vigorously.

To ascertain the distribution of Metasequoia, I interviewed many local people, but none of them knew. The innkeeper did tell me that a whole stretch of shui-shan trees might be found at Xiahoe, in Lichuan county, Hubei province, about 50 kilometers (30 miles) away. As I had almost exhausted my traveling allowance, and as communication was extremely inconvenient, I had to give up my attempt to extend my trip to that place. Nevertheless, the innkeeper had provided an important clue for a more thoroughgoing exploration later. All I could do was—taking the original spot as a center—to make a reconnaissance within the area I could cover in one day. In a few days I had collected more than one hundred specimens.

Two things impressed me deeply. One was that I came across whole stretches of Geastrum sp. (an earthstar fungus) mixed with small stones of a similar shape, forming a peculiar landscape. The other thing that impressed me was an incident. Not even by the day before my departure had I given up on the possibility of making a reconnaissance. At four in the afternoon of the last day, I met a traveler coming from the southeast and asked him where the shui-shan tree could be found. He told me that it could be got near a small village about 5 kilometers (3 miles) from where we were. Upon hearing this I almost broke into a run, intending to return to the inn before dark so that I might leave for Wanxian the next day. After trotting for a while, I met another peasant and asked him how far it was to the village. (I can’t be sure now, but it may have been Nanpin village in Lichuan county.) “Five kilometers,” he replied. Mountain people sometimes differ considerably in their gauge of distance.

I was wavering as to whether to go or not. If I should go, it was certain that I could not have returned to the inn before dark and that the innkeeper would worry. Then, too, I had already hired a man to carry the specimens for me; we had agreed on the next morning as the time for departure. I could not break my word! But finally I made up my mind to make another reconnaissance for shui-shan.

It was getting dark when I arrived at the small village. The villagers in their isolation seldom met outsiders, especially “intellectuals” such as I was. My arrival aroused their curiosity. They surrounded me, making all sorts of inquiries. But I was anxious to see the Metasequoia trees. When I was told that there were no such trees, I was very disappointed. However, I did not give up hope, and asked the villagers to accompany me to make one last reconnaissance. There was, indeed, no Metasequoia. I did collect some specimens of Tsuga chinensis, however.

I intended to return to the inn in spite of the dark night. However, the friendly villagers had already made arrangements for my food and lodging, and had warned me repeatedly of the frequent robberies on the way, insisting on my leaving the next day, escorted by some local people. Yet I could hardly fall asleep, thinking that I could not cause them so much trouble or break my word to the hired carrier. And then I thought that in the depth of the night there would be no “bandits,” since there would be no travelers to rob. So at two in the morning I awoke my roommates, explaining to them the reason for my prompt departure, and left the villagers a letter of acknowledgment. Since the door was locked, I could only jump over the wall so as not to disturb others. In the moonlight I passed through stretches of dark pines, returning to the inn before dawn. That very day I left for Wanxian.

Geomancy Spared the Type Tree

Modaoqi was a very small village, to the southeast of which stood the Chiyue Mountains. Its altitude was 1,744 meters [about 5,755 feet]. At the time it was in Wanxian county, Sichuan province. It was so called because of its situation at the source of the river. As modao in Chinese means “knife-grinding” and suggests sinisterness, the name was changed to Moudao, which means “truth-seeking” in Chinese. At present it is under the jurisdiction of Lichuan county.

Citation: Hseuh, C. J. 1998. Reminiscences of collecting the type specimens of Metasequoia glyptostroboides. Arnoldia, 58(4): 8–11.

As the local people looked upon the Metasequoia as a sort of divine tree, they built a shrine beside it. Among the villagers there were quite a few traditions about the Metasequoia. As a result, the villagers considered its fruit-bearing condition to be an indication of the yield of crops, and the withering of its twigs or branches a forecast of someone’s death. It was also rumored that, some time after the founding the Kuomin Tang government, some foreign missionaries who were passing through the village were willing to buy the tree for a big sum of money. The villagers refused to sell, however, because of the geomantic nature of the place. Thus, it was because of feudalistic superstition that the tree had survived. Its age is estimated at four hundred years.

With the advent of well-regulated highway communication, the poor village of the former days changed its aspect long ago. The Metasequoia tree, which had survived the ravages of time and is reputed to be a “living fossil,” has not only persisted, but is being disseminated. Now Metasequoia trees are “settled” in many countries of the world. It is only natural that people, when admiring this species of primeval tree, should wonder about its original habitat and should wish to know how it was discovered.

Reprinted from Arnoldia (1985) 45(4): 10-18.