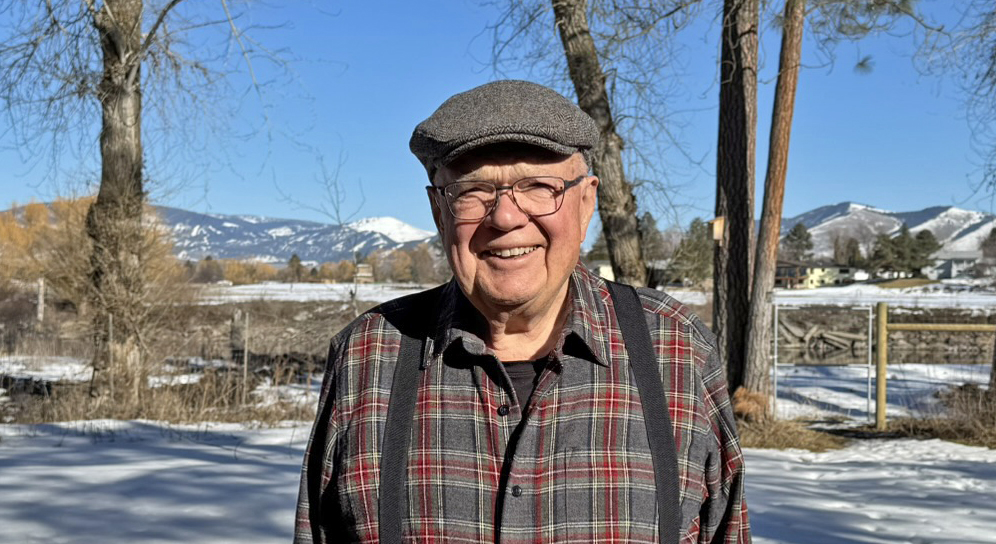

The Arnold Arboretum membership community is made up of thousands of supporters around the world, each contributing their own perspectives and histories but united in their appreciation for nature. Meet member Orville Daniels of Montana, who has felt a kinship to the great outdoors since he was a child. Orville enjoyed a storied career in forestry, and one way he stays connected to trees in his retirement is through the work of his granddaughter-in-law, Amy Heuer, Associate Director of Digital Communications at the Arnold Arboretum. Read his story in his own words.

I fell in love with forests and trees when I was young. Mostly it started when I was about 12 years old hunting squirrels in the hardwood forests of western Missouri. We were weekend farmers on a 160-acre farm that was partially forested. The “woods” for a 12-year-old was mysterious, scary, and exciting. My grandpa, who lived near the farm and practically lived in the woods, hunted for some of his food and as a result it became natural for me to be in the woods and I learned appreciation for its value from him. He had come to that part of Missouri as a 4-year-old in a covered wagon and became a pioneer who knew the woods intimately.

As for my involvement in forestry, a vocational class in high school set me on the career path based on my interest in science, the out-of-doors, and people. I knew nothing about it at the time but based on trust I went to Colorado State University for a degree in forestry and developed a passion for forests and how they function. In 1957 I graduated and started a job with the US Forest Service, starting a 40-year career in the national forests of the west. I worked in five states stretching from the southern part of Utah to Washington and have stayed active in the profession of natural resources since retirement.

In many ways trees are the pinnacle and largest living vegetation on the planet. As animals we are dependent on vegetation for our very existence, so we should care about and care for trees. Beyond that, trees are complex living beings that are still not completely understood. In the last six decades we have observed the addition of significant levels of knowledge about how forests function while recognizing there is much yet to learn…more on that later.

As to the question “why should people care about trees and green spaces,” there are so many answers to that question that it is challenging to respond. There are social, economic, environmental, emotional, and survival reasons for people in general, and for me personally, to care. Trees individually and as part of ecosystems have value.

For me personally, I often go to the forests for peace of mind and for interest about the natural world. To walk through the forests, sit and lean against an ancient tree, hear the birds and smell the air, and try to understand the wonder of the natural world. I always knew it made me feel better. Now we know those experiences even affect our brain chemistry and we have scientific proof that experiencing green spaces makes us happier and healthier.

Many studies prove trees store carbon and help offset the effects of climate change. We also know forests strongly affect the weather in areas surrounding them and even increase levels of rainfall in nearby ecosystems.

Societies worldwide rely on nearby forests for their livelihoods and even survival. Forests create a surplus of wood that, if carefully managed, can be used for housing, energy, and construction of large buildings. In the last few years, we have started to construct multi-level buildings completely out of wood. This sequestration of carbon also replaces steel and concrete, which have been significant contributors of CO2 to the atmosphere. Most people don’t know that a wooden beam in a fire will maintain its structural integrity longer than a steel beam. Steel softens and melts while wood chars on its surface remaining strong longer. Wood from trees is a useful and valuable product. When, however, we allow the economic benefits of timber production to drive the harvest of wood—in lieu of the ecosystem-determined needs and benefits—we can and have damaged forested lands and fed the environmental controversy that ensued.

Amy gave my wife (a 35-year USFS veteran) and I a full-day tour of the Arnold Arboretum and an introduction to several staff members. I was blown away by the experience. It is a beautiful and spiritual place that demonstrates professional care and scientific rigor—it is magnificent. I wish we lived closer so I could experience and learn even more from this special place.

I constantly read anything I can get my hands on about biology, ecology, and the natural world, and Arnoldia is my favorite publication. It is unique, thoughtfully edited, and informative. In fact, I eagerly await each issue and read it first. There have been too many great articles to pick a favorite. The ones on how the Arboretum is operated and managed are usually my favorite.

That brings me to the value and importance of the Arboretum itself. I mentioned earlier there is still much to learn about trees and forests. Let me explain: When I graduated with a degree in forestry seven decades ago, we were taught that we (as members of the profession) knew how forests work. However, in the years since we have learned that things are much more complex. As examples, we did not know about:

- Fire-adapted ecosystems;

- Role of fungi tying trees into networks;

- Conservation biology;

- Use of DNA to assist in taxonomy;

- Use of vegetative habitat types to map forests;

- Role of megafires and urban fires.

This brings me to the point that since we have learned so much in the past few years it follows that there must be as much still to be learned in the future. The Arboretum plays a significant role in gaining new information about trees and forests. That may be its greatest value.

Are you inspired by Orville’s words? Consider joining our community of thoughtful and passionate Arnold Arboretum members today to support our conservation, research, and civic missions!