Only Hillcrest farm boys, we’ll soon by Hillcrest men,

True and trusted citizens, we’ll work for Weston then.

Bound to make her greater far than she has ever been.

We are the farm boys of Weston.

First verse of “Hillcrest Song”

At the turn of the twentieth century, Weston, Massachusetts, was a farming town that had become a country retreat for the well-to-do of Boston. With a commuter train connecting it to downtown Boston, less than twenty miles away, wealthy families had moved westward, searching for fresh air and rural activities. Among these estates arose an unconventional operation: an experimental farm, launched in 1910, by Marian Roby Case. For more than three decades, Case conducted the operations of a remarkable educational and horticultural enterprise called Hillcrest Gardens, which made a lasting impact on the boys who participated. In 1920, a Whitman Times article by Louis Graton described Hillcrest as “a truly philanthropic institution … where boys, any boys, may receive, under expert tutoring, up-to-date instruction in fruit and vegetable growing. These boys are also taught the rudiments of good business. They are sent out with the truck, well loaded with the choice products their own hands have helped to raise … to sell and thus learn self-reliance.”

Marian Roby Case was born in Boston in 1864, the fourth and youngest daughter of merchant and banking executive James Brown Case and his wife Laura Lucretia Williams Case. In her youth and young adulthood, Marian and her family divided their time between their home on Beacon Street, in Boston, and their country place, Rocklawn, in Weston. After her father’s death in 1907, Marian, her sister Louisa, and their mother came to live year-round in Weston. Marian had inherited about ten acres of property from her father between Wellesley and Ash Streets and proceeded to purchase other nearby plots as they became available, assembling about seventy acres of orchards and arable land over the next few years.

A Passion for Horticulture

It would seem that Marian Case had always wanted to farm, as apparently had her father. When Hillcrest was established, she initiated an annual pamphlet, known colloquially as the “green books,” given the color of their covers. In the green book for 1918, she remarked, “[I] had inherited my father’s love for the care and cultivation of land. How often in travelling have I seen my father wax enthusiastic over the well-tilled acres we have passed.” At their Weston home, James Case had indulged in his avocation, at least during the family’s summer sojourns there, by raising prize livestock for exhibition at regional agricultural fairs.

The family, whose wealth came from the dry goods business, and later banking, focused their philanthropy on organizations geared towards the improvement of society. Louisa Case was a donor to the North Bennet Street School, a training program in the manual arts located in what was then a section of Boston heavily populated with recent Italian immigrants. Marian Case was an active supporter of the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, of Hampton, Virginia, through its Boston association. The institute, whose most famous graduate was Booker T. Washington, sought to educate black students to create future leaders in education, farming, and business, and it is now known as Hampton University. Its programs stressed not only instruction in practical skills but had a deep grounding in ethical and cultural improvement.

These training programs gained traction in Boston during a nationwide boom of secular and religious progressive activism in the second half of the nineteenth century, which aimed to address, among other things, rising income inequality. Andrew Carnegie famously outlined a vision for philanthropy in an 1889 North American Review article, in which he condemned ostentatious uses of wealth and urged that charitable giving should provide training and educational opportunities for the poor. James Case, for his part, attended monthly dinners hosted by the Unitarian Club, in Boston, where speakers often encouraged the affluent attendees to use their wealth for abolishing social hierarchies.

In 1909, Marian Case’s staff began preparing the land for the next year’s farming season. The first eight Hillcrest boys were hired in 1910. This number steadily increased in subsequent years until it topped out at about twenty. The youngest were generally twelve years old, although occasionally some were younger. They worked half days for one dollar per week for the first two summers they were employed at Hillcrest. From the third summer and any summers thereafter, they worked full days and could earn up to twenty-five dollars per month. The pay was lower compared to other local farms, but each boy also received a new uniform every year, which looked rather like those of the Boy Scouts of America (an organization with complementary progressive ideals, which was also launched in 1910). The uniform consisted of two shirts, two pairs of pants, a Norfolk jacket, a tie, and a broad-brimmed hat. The boys also received a gift of educational enrichment more valuable than mere clothing in the form of lectures, study periods, journaling, report writing, and personal coaching on summer-long projects that fostered observational and writing skills. Case, following the model of the Hampton Institute, wanted to provide growth opportunities for the boys so they could develop into future leaders of their communities.

We know a great deal about Hillcrest from the yearly green books, which provided a thorough review of the activities on the farm each season. The publication highlighted the reports presented by the boys during their annual convocation ceremony held on Labor Day, and these were interspersed with narratives written by Case, which provide a window into her thoughts and aspirations for her enterprise. It is interesting to see the degree to which the boys’ papers became longer and more detailed as the years progressed. Some of this may be due to increased coaching that Case and her assistants were giving to the boys, but it also came from Case’s desire to make the green books a resource for aspiring gardeners worldwide. We see articles by the boys to which Case had her farm manager Peter Mezitt—who founded Weston Nurseries in 1923—add additional material to explain a concept or technique more fully.

Expert Instruction

The boys’ days were not entirely given over to farm labor at Hillcrest; Wednesday afternoon lectures were a weekly feature of the Hillcrest program. Hillcrest boy Ernest Little described them in 1935: “One of the many advantages derived from Hillcrest Gardens is a series of instructive lectures planned by Miss Case. The program is so arranged that it includes every field of horticulture, floriculture, and botany here and abroad. They are given by leading men who are authorities in their particular line. It is with the greatest of pleasure that we welcome some of them back year after year.”

The speakers, of which there were well over one hundred by the time Hillcrest ceased operations, included a number of staff members from the Arnold Arboretum: John George Jack, who in nearly fifty years at the Arboretum was an educator, plant explorer, and dendrologist; Ernest Henry Wilson, one of the greatest plant collectors of the early twentieth century; Edgar Anderson, a geneticist and public outreach coordinator; Elmer Drew Merrill, the director (initially the supervisor) of the Arboretum from 1935 to 1946; and William Judd, a longtime propagator. Other speakers included horticultural publisher J. Horace McFarland; Arlow B. Stout, a plant breeder and research scientist at the New York Botanical Garden who spoke a number of times over the years on hybridizing and other aspects of plant propagation; John Caspar Wister, a longtime friend of Case who was a celebrated horticulturist and landscape designer; Edward Farrington, the editor of Horticulture magazine; and the Dahlia King of East Bridgewater, Massachusetts, J. K. Alexander, great-grandfather of our retired Arboretum propagator, Jack Alexander.

Beginning in 1924, Case began to invite former boys back to speak at the Wednesday lectures on their experiences in business or in higher education. Brothers Joseph and E. Stanley Hobbs spoke on their respective paths into medicine and dentistry; Edmund Mezitt, whose father Peter had been employed by Case before founding Weston Nurseries, spoke about commercial horticulture; and Charles Pear lectured on his work as a weather researcher at the Blue Hills Observatory. By bringing the so-called old boys back to lecture before a new generation, Case demonstrated the success of her pedagogy at Hillcrest; boys were indeed being cultivated into active contributors to society.

Cultivating Young Scholars

As part of the educational component of Hillcrest, the boys were expected to keep a daily journal of their work and record their observations of the plants, insects, and weather. To this end, they were each given a notebook, pencils, and drawing paper at the start of the season. They had a daily study hour during which they could research, write about their experiences, or draw. Case worked with them personally on Fridays, critiquing their reports and coaching them on their public speaking. She also enlisted a long-serving group of local educators, including Joseph Gifford, an oratory instructor from Emerson College who worked on voice training with the boys.

The summer activities culminated with the Labor Day exercises. The boys assembled and marched in carrying both the American flag and the green-and-gold flag of Hillcrest. The audience then stood for the Pledge of Allegiance, and the boys sang the Hillcrest song. Case, as mistress of ceremonies, then welcomed the guests and introduced the people who would be the judges for the boys’ presentations. Each of the boys read a paper they had prepared on a subject having to do with the farm. At the conclusion, the judges withdrew and chose the winners from the younger and older boys. Prizes were awarded for the papers read that day, as well as for their work in the field and in the classroom over the summer. Boys who had successfully completed one summer with distinction received a Hillcrest pin. Boys who had completed three or more summers with distinction received a pin bearing the Hillcrest motto, Semper Paratus, “Always Ready.” The boys’ families were encouraged to attend, and in some years, the boys were allowed to invite a girl as a guest. The subjects of the boys’ papers tended to repeat from year to year. There was always a report on the Wednesday lectures, the weather, and a review of the season, which would suggest that the boys chose their subjects from a list of topics provided by Case.

In the 1939 green book, Case thanks Charles Sprague Sargent, the late director of the Arnold Arboretum, for his support of Hillcrest, saying, “Soon after Hillcrest Gardens was started Professor Charles Sprague Sargent became interested in our work and helped us in many ways by giving us beautiful lilacs and other shrubs and trees, and by letting us go to him for advice.” Sargent also persuaded Case to sponsor an essay contest for students in the Weston Public Schools. From 1921 to 1932, junior high school and high school students wrote papers on subjects suggested by Case. Unlike the summer program at Hillcrest, this essay contest was open to both male and female students, and the girls took most of the prizes over the years.

Cultivating Young Horticulturists

From the earliest days of its operations, Hillcrest’s crop production was tailored to the preferences of its customers. In the 1913 green book, Philip Coburn, who had for the previous three summers conducted door-to-door sales in Weston, writes that when the seed catalogs arrived in the winter, he and Mr. Hawkins, one of Case’s full-time farm employees, chose the coming season’s seeds with an eye to customer favorites. During Hillcrest’s first decade, direct sales were conducted in Weston and the nearby towns of Auburndale and Waltham, by horse-drawn wagon and concurrently by truck. Produce was occasionally carried as far afield as the historic Faneuil Hall marketplace in downtown Boston. By the farm’s second decade, a summer stand opened in Weston near the village blacksmith on the Post Road, and door-to-door sales in town and in Auburndale were discontinued. Instead, direct marketing was concentrated in Waltham, as the dense population allowed for the best return on their efforts. Farm production catered to this primarily Greek and Italian clientele, with tomatoes, peppers, eggplant, and parsley. Sales at the market continued until 1930 when it was decided to provide Hillcrest’s produce to a Weston grocer who would then handle all the cash transactions and bookkeeping.

Case was eager to trial new crops. She developed a relationship with David Fairchild of the Office of Seed and Plant Introduction at the United States Department of Agriculture and received from him new seed introductions for testing. Likewise, in 1910, Case hired Chen Huanyong (Woon-Yung Chun), a Chinese undergraduate from the Massachusetts Agricultural College in Amherst, to take charge of the boys. He worked at the farm for five seasons until 1919. Meanwhile, in 1915, Chen enrolled in the New York State School of Forestry at Syracuse University, and after his graduation he came to Harvard’s Bussey Institution and studied with John Jack at the Arboretum. Chen returned to China in 1919 and later became a professor at Sun Yat-sen University. Over the years, he sent seeds for many varieties of Chinese vegetables, including eggplant, cabbage, watermelon, and bok choy, which were excitedly planted and proved popular. Seeds also came from Case’s friends in Italy with whom she often wintered, including zucchini and small white eggplants.

In the present day of housing subdivisions and strip malls, it is easy to forget just how rural Weston and its neighbors, Sudbury, Wayland, Lincoln, and Wellesley, were one hundred years ago. In the early years of her enterprise, Case fretted as to whether Hillcrest was cutting into the business of other local farms. She had to strike a balance between selling their produce inexpensively but not selling it at such a low price as to undercut the other farms in town. In the 1918 green book, she wrote about discussing these issues with members of the local agricultural society: “Last spring we made thorough inquiries as to whether Hillcrest was harming the other farmers of the town and were told decidedly no. One of our well known townsmen said, ‘Hillcrest is doing good work. It is interfering with nobody. Go ahead.’”

The Hillcrest Boys

Initially Case limited the Hillcrest program to boys from Weston but very soon expanded it to include boys from Waltham and further afield. For the period, she was remarkably progressive in her acceptance of boys for the program, welcoming sons of old Yankee families, as well as recent immigrants from southern Italy and the eastern Mediterranean, and the son of her African American butler, George Weaver. Her mentorship, respect for, and longstanding relationship with Chen Huanyong also point to her progressive ideals. In an age when children were to be seen but not heard, Hillcrest boys were encouraged to speak and make their opinions known. In fact, as Case said in 1922, “There is no sectarian or political influence exerted at Hillcrest Gardens; each boy has a right to his opinion, whether we agree with him or not.”

Harold Weaver, the first boy enrolled at Hillcrest, participated for six seasons. He was also the first of the Hillcrest boys to go to France, in 1918, with the American Expeditionary Forces of World War I, as part of the 369th Infantry Regiment, the all-black unit nicknamed the Harlem Hellfighters. Case published an excerpt from a letter he wrote from “somewhere in France,” in which he said, “You do me honor, Miss Case when you tell me that I am the first Hillcrest Boy to come to France. My Hillcrest pin is ever with me on the lapel of my blouse. I often look at it and think how I should dislike to lose it in No Man’s Land and how I hope to bring it safely from No Man’s Land to Weston again so that you yourself may see the pin that has travelled 4,000 miles.” Case went on to name two other students who were serving in the military: one as an aviator in Texas, the other in the Marines. Weaver was commissioned a second lieutenant in France, perhaps due in part to the leadership skills he learned at Hillcrest. He and the other Hillcrest boys in uniform all returned safely from their service in the armed forces at the close of the war.

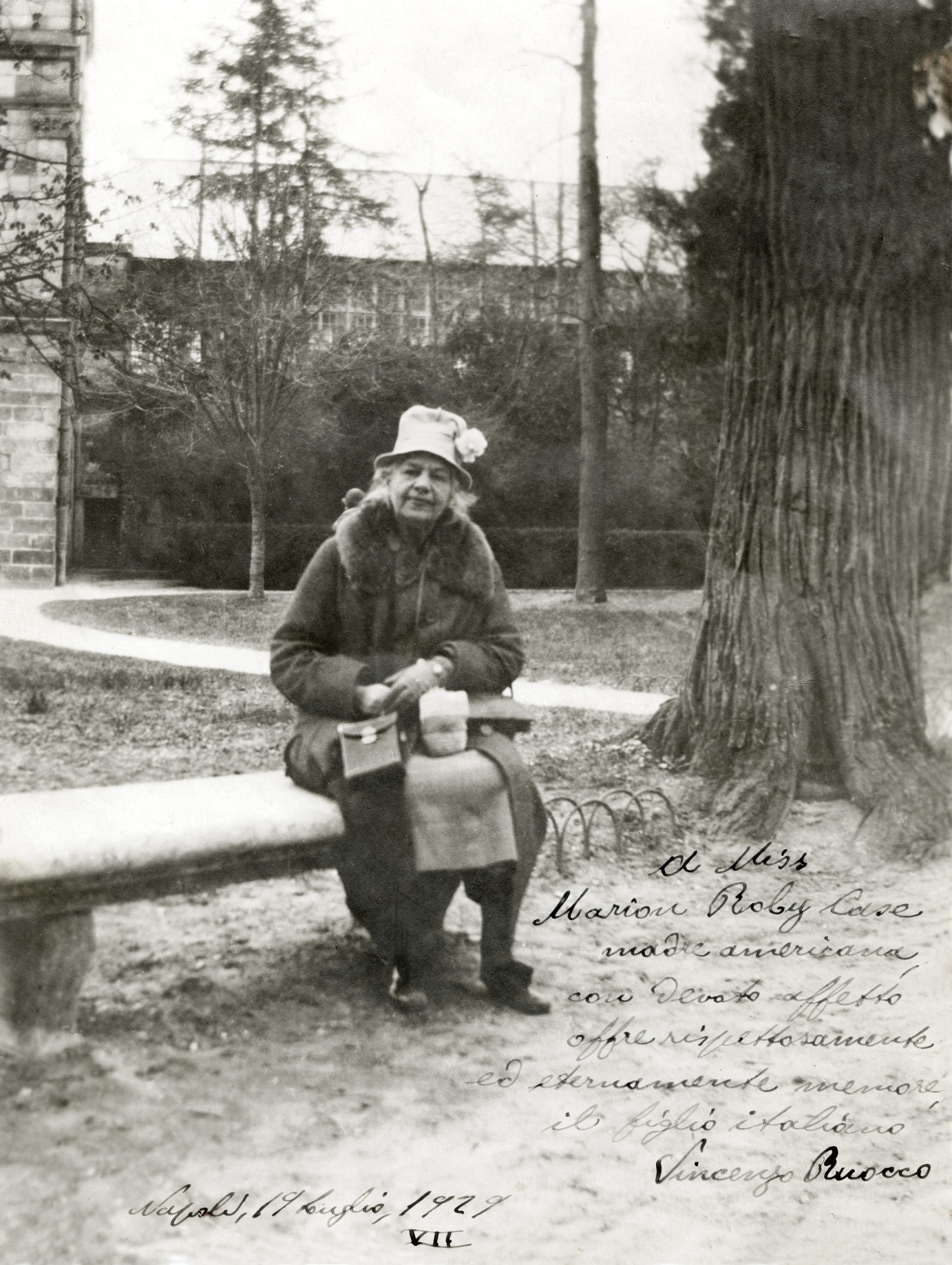

Case never married and had no children of her own, but she nevertheless became a second mother to about one hundred Hillcrest boys whom she guided firmly but lovingly. In 1923, she reflected on her satisfaction in one of the boy’s papers, noting that his “tribute is very pleasing to one who has tried to mother the boys, and who through a long life has seen mistakes which she feels that the training in sturdy independence, responsibility, individuality and co-operation which the boys have at Hillcrest Gardens may help to overcome.” The loving regard with which Case was regarded by the Hillcrest boys is clear in their writings and later reminiscences. Case seemed to inspire affection wherever she went. She was photographed by a friend, Vincenzo Ruocco, in Naples, Italy, in 1929, and he inscribed the picture, “A Miss Marian Roby Case madre americana, con devoto affetto offre rispettosamente ed eternamente memore il figlio italiano.” The note roughly translates to, “To Miss Marian Roby Case, American mother, offered with devoted affection, respectfully and eternally, from her Italian son.”

Transitions

As Case became older, she began to cast about for a successor organization to take over Hillcrest. She considered the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, the University of Massachusetts, and other organizations, settling upon the Arnold Arboretum in 1942. The Hillcrest property was acquired by the Arboretum through bequests and donations by Case and her sister Louisa that occurred between 1942 and 1946. It was renamed the Case Estates and consisted of the family homestead, Rocklawn, and additional parcels of land and buildings acquired by Case. As part of the Arboretum, the property’s main function was to provide additional nursery space for our living collections and to serve as a horticultural experimentation area. Weston’s colder temperatures meant that plants that proved hardy there would definitely be hardy in the more temperate climate of Boston. In the 1950s and 1960s, experimental plantings and trial gardens were introduced to show plants, including herbaceous material, which would be appropriate for suburban home landscapes. The Case Estates buildings provided housing for staff and space for educational programs and public events. Case’s will did not impose any restrictions on her bequests to the Arboretum, and she realized that, as times changed, the Arboretum might desire to sell the property, in which case she directed that the proceeds of the sale should be added to the general endowment. This outcome occurred in 2017 when the remainder of the property was sold to the town of Weston.

In creating an educational work program for boys, Case sought to encourage future farmers, as well as leaders in whatever field a boy chose to pursue as his life’s work. Women might well ask why she did not extend this program to girls. The answer is in the social mores of the era in which Hillcrest was conceived. In 1909, women were only starting to make their way into the public sphere, and it would have been very unusual for mixed groups of girls and boys to work together doing farm labor outside of a home situation. This was the era when school entrances had separate doors for boys and girls. Case grappled with what work was appropriate for the younger boys finding that the heavier farm labor was too much. Times, however, were changing. The progressive forces that inspired programs like Hillcrest were complemented by advocacy for women’s rights, which extended beyond the right to vote. Pioneering women, especially the “farmerettes” of the Women’s Land Army in Britain and the United States during World War I, led the change, and Case knew that a female horticulturist could be the match of any man.

Citation: Pearson, L. 2019. Marian Roby Case: Cultivating Boys into Men. Arnoldia, 77(2): 2–9.

“Sometimes I feel as if I would like to have a woman take care of my flower garden at Hillcrest,” she wrote in Horticulture magazine in 1920. “For as a rule women are better nurses. Men are good for spring and autumn work. They can plant, do good landscape work, go in for effects. But when it comes to the care that plants need in summer, the watching, nursing and babying I believe that women will prove better.” She went on: “There are some men who have this woman element to a large degree—not the feminine, there is a difference—of them, poets, artists and good gardeners are made. The marking of crosses on a piece of paper is not going to make any difference in the spirit of womanhood in either man or woman and there is still truth in the old saying that the hand that rocks the cradle is the hand that rules the world.”

Lisa Pearson is head of library and archives at the Arnold Arboretum. Her book Arnold Arboretum was published as part of the Images of America series in 2016. She had the pleasure of meeting two of the “old boys” from Hillcrest Gardens, Jack and Tom Williams, about fifteen years ago. They both spoke of Case in affectionate terms.

From “free” to “friend”…

Established in 1911 as the Bulletin of Popular Information, Arnoldia has long been a definitive forum for conversations about temperate woody plants and their landscapes. In 2022, we rolled out a new vision for the magazine as a vigorous forum for tales of plant exploration, behind-the-scenes glimpses of botanical research, and deep dives into the history of gardens, landscapes, and science. The new Arnoldia includes poetry, visual art, and literary essays, following the human imagination wherever it entangles with trees.

It takes resources to gather and nurture these new voices, and we depend on the support of our member-subscribers to make it possible. But membership means more: by becoming a member of the Arnold Arboretum, you help to keep our collection vibrant and our research and educational mission active. Through the pages of Arnoldia, you can take part in the life of this free-to-all landscape whether you live next door or an ocean away.