“We are continually overflowing toward those who preceded us, toward our origin, and toward those who seemingly come after us…. It is our task to imprint this temporary, perishable earth into ourselves so deeply, so painfully and passionately, that its essence can rise again ‘invisibly,’ inside us. We are the bees of the invisible. We wildly collect the honey of the visible, to store it in the great golden hive of the invisible.”

Rainer Maria Rilke

Say a lone honeybee, foraging for nectar, lands on a hidden patch of goldenrod several miles from the hive, on the other side of the mountain, in a little clearing next to a stream. In the afternoon sun, she drinks from some 50 to 200 flowers, until she is full. Then she flies back to the hive. Upon return, when her sisters see her, she vibrates her wings and abdomen at a particular amplitude, frequency, and angle—a certain shake, a certain quiver. She pivots in a figure-eight pattern in space, beating her wings as she cuts a straight line, then turns in a circle and holds her wings still.

With these complex gestures, the bee communicates the direction of the food source relative to the sun’s position in the sky; the duration of the dance indicates how far away the nectar lies. It is a dance performed for a singular occasion, constituting a kind of ephemeral archive, a record of the route to the nectar that fuels her dancing—a language, certainly. Having witnessed the dance, the other honeybees will find the patch of goldenrod blooming on the other side of the mountain and drink from it. The hive itself, its cells packed with honey, houses a physical record of every single wildflower that was visited by members of the hive in one place on Earth in a passing season, the sweet essence of each flower, inscribed into invisible-to-the-eye DNA traces. A drop of honey on your tongue is an archive of nectar slurped by the bristly tongues of forager bees, spit into the mouths of worker bees at the hive who held it under their tongues until it turned to honey, then stored it in cells within the hive.

The word archive can be traced to the Greek arkheion. The French philosopher Jacques Derrida tells us in Archive Fever (1995) that the arkheion was a house, a dwelling-place of the magistrates, where official documents were filed and stored. This leads us to the Greek oikos, the home or dwelling of a common person, the word that is at the root of ecology, and so ecology is the study of the home, every home an archive of ecological events and relationships.

VISITING THE ARCHIVES at the University of Georgia, I landed on the 28-box collection of a botanist named Marie Mellinger. Born as Marie Barlow in 1914 at the edge of a forest in Wisconsin, she settled with her husband Mel Mellinger in Rabun County, Georgia in 1958, where she lived until her death in 2006.

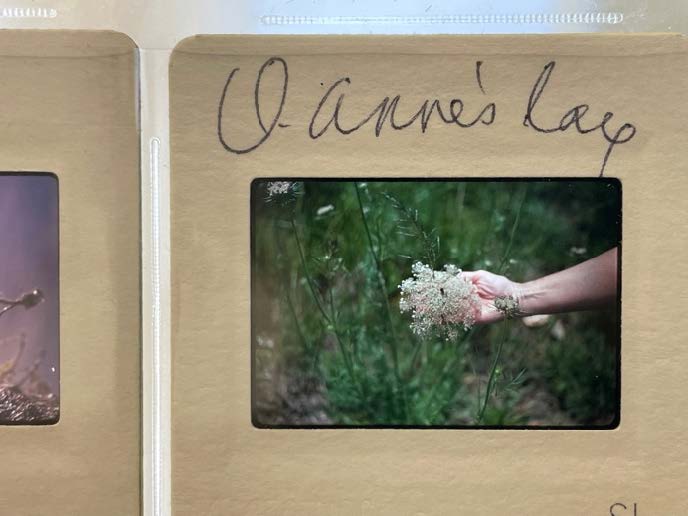

A self-taught naturalist, she “built a scholarly reputation through exhaustive botanical surveys,” according to her obituary, and penned the Atlas of the Vascular Flora of Georgia. She became the first non-Atlanta president of the Georgia Botanical Society. The collection holds her scrapbooks of pressed flowering plants, an extensive and meticulous index of flowering plants with citations to published works that give further botanical information, clippings of stories about Mellinger from local and regional newspapers, and several sleeves of her 35 mm Kodachrome film slides of plants and landscapes.

As I dug through, I came across a hefty box containing Mellinger’s recipes for dishes prepared with wild edible plants native to or naturalized in the mountains of North Georgia. The box was stuffed full of hundreds of recipe cards, so packed with them that there was no empty space in which to flip the cards from one to the next, and I had to pull each one out to read it. I was immediately enamored with recipes for stews of chickweed, salads of cress and cattail shoots, wood-sorrel sauces, walnut-persimmon cakes, sautéed kudzu, and birch-leaf tea.

Recipe boxes have been kept throughout written history in the homes of common people—women, mostly, in the cabinets and on the counters of kitchens, the cards inside accruing splatters and stains over time from boiling pots and dripping spoons. Though they constitute significant archival efforts, these rich collections are rare in “the” archives, considered less significant in the annals of history filed at the houses of the magistrates.

Derrida reminds us that the archive is jussive—it decides not only what is remembered but what is memorable. The recipe boxes of mothers and grandmothers have been passed to daughters and granddaughters, home to home, living archives to which new recipes are added, old recipes pulled out of the box again and again. They were not deemed as memorable in official history as a host of men’s affairs were, though eating is the daily act that has fed and nourished everyone throughout history.

Records of foraged meals are even less archived, it seems, and this is what caught my eye about the box in the Marie Mellinger collection. They pointed not only to a meal prepared and eaten but to the unwritten, singular acts of gathering that the meals’ preparation required each time. These recipes gestured viscerally toward the mountains and fields beyond the kitchen in which Mellinger cooked, the oikos that gave her life sustenance.

Mellinger’s meals of wild edibles collected throughout the 1970s were set apart from the storebought culinary culture that rose to ascendance in the 1950s and still constitutes the industrial mainstream (which speaks also to ecological relationships), and even from the meals that one might prepare with vegetables harvested from a garden. They suggested not only field but forest, not only fertile valley but windswept ridge. A woman’s life not confined only to the grocery store or kitchen. A wider, wilder frame. To me, the box of recipes painted an intimate portrait of a life lived in a particular place on Earth, and its many passing seasons. A forager myself, for days I rifled through the box, as if to satisfy a hunger, to drink a nectar. Purslane pickles, burdock candy, dandelion coffee, smilax jelly, mulberry spritzer, sassafras tea, elder flower fritters, stewed chicken of the woods mushrooms.

Sitting in the quiet, stale, and light-filled reading room of the university’s archives, reading the recipes, I thought of roaming the woods. It was the middle of March, and sorrel was speckling the forest floor. Instead of sitting there, I might have been picking the heart-shaped leaves of violet and collecting them in a basket for a salad. It was the time to harvest chickweed, too, the leggy stems of which I would chop with my knife and blend with olive oil to make a green pesto. I would have liked to forage, to make a savory pie with henbit and cleavers. But I was held spellbound inside, foraging for sustenance of a different sort—a kind of sweet essence.

Mellinger’s archive of recipes made with foraged plants is not like the hive-archives of bees, not itself an edible honey. Yet, it is a record of wild plants that bloomed and grew, that were collected and eaten throughout a lifetime. The box of recipes seemed to be a record of motions as fleeting as the visitation of bee to flower.

WHILE ALIVE, Mellinger showed hundreds of people the path to the hidden patch of goldenrod on the other side of the mountain, leading a group she called Incredible Edibles. For some four decades, she took participants (many of them the young people of Rabun County, Georgia) on foraging walks and hosted meals. The tradition of foraging has been carried on primarily this way. A person follows another person, who spots something growing that she likes to eat, snaps off a stalk or pinches a leaf, says, “Here, taste this,” says, “Let us gather some, for soup.”

There are subtle cues involved in the positive identification of a plant—a certain wintergreen scent in the bark of cherry birch (Betula lenta), say, that distinguishes it from black cherry (Prunus serotina), or the instant heady-spicy aroma when one crushes a spicebush leaf. The nuance of purple spots on the smooth stalks of water hemlock that communicate “poison,” compared to the very fine hairs on the spotless stalk of wild carrot, hemlock’s close relative, that say “safe.” The texture of a leaf, its roughness, fuzziness, or smoothness, can conjure a name without hesitation. Information like this has been passed down from sensing body to sensing body for hundreds of thousands of years.

Wendell Berry has written that “(e)ating is an agricultural act.” Foraging precedes the dawn of agriculture, and yet it points to an attentive relationship with plants as the foundation of human culture, much more ancient in our species’ DNA (~300,000 years) than the somewhat recent domestication of seeds (~10,000 years). The survival of our species is thanks to generation after generation being shown the path to plants that were edible and nutritious.

Agriculture suggests fields as opposed to forests, but foraging might be done in any terrain at all where people roam and plants grow, and forests are particularly rich sites in this regard. Archaeologists now understand that where colonizers perceived vast stretches of untended forests, or “wilderness,” in North America, they failed to see the signs of the tending, cultivation, and harvest of wild plant populations that Indigenous cultures practiced in woodlands. More than mere gleaning, foraging entails caring for patches of plants or stands of trees so that they might continue to grow and bear fruit in perpetuity.

I observed this years ago when I was writing about wild ginseng, a plant whose populations have been severely depleted due to overharvesting. A man in the mountains of East Tennessee led me through the woods to “his” patch. Every fall, he carefully gathered the berries and planted them, nurturing the growth of new seedlings. He had a method for keeping the ginseng well-hidden, so that it wouldn’t be poached by “’sang” hunters who wanted to dig its roots for their high cash value on the global market.

Mellinger packaged the seeds of around 600 of her favorite species of wild plants gathered on her foraging walks, sealed them in little envelopes labeled with their botanical names, and distributed them around North Georgia. Among them were goldenrod, sourwood, pokeberry, and yellow-eyed grass. She never revealed where she found rare plants. She lamented the increasing rarity of Hydrastis canadensis, or goldenseal, another plant harvested for medicine. She opposed the gathering of plants for herbaria, which she thought could be replaced by the use of photographs. “Think before you clear land or cut anything,” she advised citizens in an interview with a local newspaper. Near the end of her life, she began to speak out strongly against pesticides. When I opened the box of recipes, placed atop the cards longways was a folded clipping from a magazine about the harms of pesticides and herbicides.

If practiced as a stewardship, foraging can encourage populations of wild plants to become more robust and widespread. It can give reason to protect land and conserve forests. If not practiced carefully—full of care, that is—it carries the danger of eradicating wild and medicinal plants from their habitats. Forests and the wild edges of fields, and all places where plants grow and people roam, are also archives, then, tended to by their cultures. They are deep stores of history that can tell us much about the past and the relationships that people have had to plants and trees in particular places. A forest is a dwelling-place, or oikos, that must be preserved, while at the same time it serves to preserve its attendant human cultures and provide sustenance and medicine in the present day.

During a seminar she taught at the Hambidge Center called “Reading the Landscape,” Mellinger led participants to a Southern Appalachian mountain cove, past a fallen chestnut—dead half a century, since the chestnut blight, imported accidentally on Asian trees, swept through and eradicated the primary wild food source of Eastern forests. She gathered the group under a beech tree, her favorite species of tree, with which she liked to make “coffee” from the roasted nuts, and a tonic from the young leaves. “Today I have grown taller from walking with trees,” she read from a paean to forests she had composed from various sources. “I would not say that trees at all were of my blood or race, yet lingering where their shadows fall I sometimes think I trace a kinship.” Mellinger cried, her tears dropping into the leaf litter.

“I get very emotional over forests,” she told an interviewer who attended the seminar, “because the forest means something special to me. The feeling I have about forests is—well, it’s just something you absorb when you live with a forest.” I imagine her sipping roasted beech-nut coffee, baking persimmon- beech-nut bread. In Archive Fever, Derrida discusses Freud’s “death-drive,” which “destroys in advance of its own archive.” The act of eating might be seen as this, a sort of anti-archival act, as the food is destroyed after it is harvested, consumed, and leaves no record. But our bodies are also archives, housing the seasons of eating. In foraging, as we eat and imbibe the plants and trees near us, we absorb the forests with which we live.

Practiced as a stewardship, foraging can encourage populations of wild plants to become more robust and widespread.

Paleontologists who analyzed the mummified corpse of a man who lived around 5,000 years ago in the Alps (now known popularly as Ötzi) found in his stomach the pollen of the hop hornbeam and hazel trees that were blooming at the time of his death, in late spring; undigested einkorn wheat, harvested and stored from the previous fall; six different mosses; fern spores; pine pollen, and the pollen of 30 other plants and trees.

“Live in each season as it passes; breathe the air, drink the drink, taste the fruit, and resign yourself to the influences of each,” Thoreau wrote in his journal in August of 1853. He was known to rhapsodize about picking and eating wild blueberries and huckleberries. As seasons layer into years, every forager knows, each season becomes a store of memories of previous years: what popped up, leafed out, ripened, budded, flowered, fruited at a given time, what was cooked and eaten when the angle of the setting sun was just so, the bite in the air of a certain sharpness.

And every year we are a little older, our bodies accumulating more records. In this way, we are something like trees, with their concentric rings that tell of drought years and fat years, and their scars from limbs lost, the marks of each year’s new growth, and wind-bent crowns. So also our teeth, bones, hair, and skin house histories of the years, of minerals and other traces of our living. The journalist who wrote about Mellinger’s seminar described her cheeks as “weathered.” Ötzi’s skeleton indicated that he had spent his life walking over mountainous terrain. The feeling Mellinger had about forests, she said, was just something you absorb when you live with a forest.

IN THE ARCHIVES, I pulled out recipes from the box. Basswood-flower fritters. Young violet-leaf appetizers (fried, splashed with orange juice and sprinkled with sugar). Plantain, mustard, and blackberry greens, boiled. Baked dandelion roots. Sumac-ade, sweet birch tea, Blue Mountain Tea. I had seen reference to Blue Mountain Tea before in Appalachian herbalism. It is made with Solidago ordora, a fragrant species of goldenrod. “Delicious hot or cold,” Mellinger typed on the card. “Steep by pouring water over leaves until pale golden color.”

There are cards that list entire menus, no doubt prepared for Mellinger’s Incredible Edibles group. I pulled one labeled “Saturday dinner, Oct. 4, 1975.” It listed a Qualla-mint cocktail, fried yarrow appetizers, chestnut soup (it must have been made with the nuts of the imported Chinese chestnut, as there were almost no wild American chestnuts left standing at that point), broiled chicken with an herb sauce, and dandelion greens.

Qualla refers to the reservation land of the Eastern Band of the Cherokee, some fifty miles to the north of where Mellinger lived in North Georgia, which had also been part of the wide Cherokee territory up until the 1830s. Perhaps she referred to a type of mint specific to that region and known colloquially as Qualla mint. References like these reflect the connections to Indigenous practices that run through the settler-colonial traditions of foraging in North America.

One of the earliest encounters with foraging that I remember was in the Great Smoky Mountains, the heart of the Cherokee homelands, where I grew up. As my mother and I walked along a trail, we approached a man who had just put a twig into his mouth. He greeted us by reaching up to a branch to break off a small twig like his, and held it out to me, smiling. “Here ya go, chew on this—Indian toothbrush!” When I chomped down, its minty-green freshness winged through me like the flash of a cerulean warbler, vivid. Who were these “Indians” who invented such toothbrushes, I wondered, and what else could I eat that they did? Their presence loomed large in the mountains, in the names of plants like Indian cucumber (Medeola virginiana, with a crunchy, cucumber-like tuber), Indian strawberry (Potentilla indica, with an edible, though somewhat tasteless berry, of which I ate as many as I could find when young), and Indian banana (Asimina triloba, or pawpaw, North America’s largest native fruit).

In such names we see both the presence and the erasure of Indigenous cultures. Another of Mellinger’s menu cards is labeled, “Cherokee Atohuna Feast, 1978.” It lists sumac-ade (brewed from the berry of what is considered one of the richest native sources of ascorbic acid, or Vitamin C, in Eastern forests, it is sour like lemonade), sliced artichokes, toasted nuts, chestnut soup, turkey-wild rice stuffing with greens, corn papas in corn husks, sorrel salad, persimmon-Indian pudding, and sassafras tea.

With a quick search, I learned that the Atohuna festival of the Cherokee was one of seven sacred festivals, held ten days after the new moon of October, which was itself celebrated as the new year. The Atohuna, or “friends made” festival, was a time when new friendships were honored with vows and old friendships were reconciled. What are we to make of this recognition of, and appropriation of, Indigenous culture within settler-colonial foraging traditions? When we eat the wild foods once eaten by Indigenous people who were dispossessed of the lands on which we forage, how can we, as descendants of settlers, or even as temporary visitors, honor the long lineages that preceded us while not appropriating them? How can an awareness of Indigenous histories call us to better stewardship?

In a scholarly article published in Appalachian Journal the year before Mellinger recorded her CherokeeAtohuna feast, she wrote:

The history of Appalachian medicine plants goes back far beyond the coming of the first white settlers. The Cherokee Adowahis (shamen), either male or female, knew and used over 600 plants.… All were gathered at the proper time of the year with the proper chants and incantations. Barks, for example, were always gathered from the east or “spiritual” side of the tree. This same custom was later followed by the mountain settlers when gathering oak bark. They believed that bark gathered from the east side of the oak had more medicinal value, not realizing that they were still appeasing a Cherokee spirit.

As Cherokee were displaced and later removed from the region, remnants of their knowledge were carried on by settler-colonists and became suffused with Appalachian culture. Mellinger continued the article with a lament of the extreme overharvest of both ginseng and goldenseal, two of the most revered plants to the Cherokee. While part of the foraging traditions were preserved, along with the recognition of the plants’ “almost magical healing powers,” they were enfolded into a global capitalist economy that has almost completely eradicated the plants from the wild. “So many tons of [ginseng] have been dug up and exported to oriental markets,” wrote Mellinger, “that [the root] has become a rare and endangered species in many parts of the mountains.”

Dr. Clint Carroll, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation and associate professor of Native American and Indigenous Studies at the University of Colorado, says that reciprocity is the foundation taught to him by the elders of his culture, and that non-Native foragers should ask themselves what reciprocity they are engaged in as they strive to establish connections to the land through foraging.

We are called to honor the plants themselves and their growth in the wild as inherently and unimaginably valuable, over and above the archives of them.

Mellinger wrote of the Cherokee conservation practices that had once ensured ginseng’s continued thriving: “The Adowahi would seek the plant in the fall of the year when the seeds were ripe, bypass the first three plants and dig the fourth, leaving its seeds, with red and white beads, in the hole for compensation. The Adowahi would ask permission of the mountain to take a piece of its flesh (the ginseng root).” For the Cherokee, the mountain as archive lent out its flesh by permission; the forest as oikos housed a botanical library that was the responsibility and living treasure-house of a rich human culture.

“Non-Native foragers might easily assume that Native people to the area where they’re foraging were once here and are no longer,” Carroll says. However, “They’re still here, and they still want to connect with lands that they were dispossessed from.” Awareness of Indigenous histories must be followed up with commitment to the current struggles of Native communities to connect with land and continue their traditions of stewardship. “Foragers must push themselves to not only acknowledge Indigenous absence but also work for land back for Native people. There are better futures, if we can think of how to enact them and realize them.” Carroll worked to pass a plant-gathering agreement between the federally owned Buffalo National River and the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma so that Cherokee people could continue traditional cultural practices of foraging that they are unable to on their limited tribal lands.

To honor the Cherokee lineage of land ethics, we are called to begin conversations about the rematriation of Indigenous lands. We are called to conserve forests and protect land, and to abstain from harvesting rare plants. I think of the locked vault in which the rare books are stored in the archives, the reverence with which we breathe as we leaf through the books, the care with which we turn the pages of seventeeth- century herbals like Culpeper’s. Carroll tells me about the Cherokee tradition of foraging shagbark hickory nuts each fall for a soup called kanuchi. As I ponder seeking out the fallen hickory nuts later in the year, I want to carry the weight of Carroll’s invitation to solidarity into the forest with me.

“It is our task to imprint this temporary, perishable earth into ourselves so deeply,” wrote Rilke, “so painfully and passionately, that its essence can rise again ‘invisibly,’ inside us. We are the bees of the invisible. We wildly collect the honey of the visible, to store it in the great golden hive of the invisible.”

WE ARE CALLED to honor the plants themselves and their growth in the wild as inherently and unimaginably valuable, over and above the archives of them. Mellinger criticized another Georgia botanist who found a grove of shooting-star (Dodecatheon meadia) and dug 60 “specimens” of it “to press between paper and send off to other botanists, who in turn might go out and decimate other colonies of other wild flowers in other places in order to return the favor.”

In the arkheion, the house of the magistrates, we see “ark,” which is not etymologically related, and yet it is visible there, and audible in “archive,” conjured by it. The ark is the figurative place of refuge, a place where we store what might otherwise be lost. Storing pressed plants does not preserve them in the wild. Storing recipes of dishes made with wild edible plants does not preserve the tradition of foraging the plants, preparing the meals, and sharing them with others. The librarian and digital-humanities leader Bethany Nowviskie invites us to understand all collections, including those in natural-history museums, like pinned butterflies and honeybees, as “archives of the Anthropocene,” “archives of diminishment.”

What is the great golden hive of the invisible in which we store the visible honey? I pulled out cards from the recipe box and pored over them. Some of the cards don’t contain recipes but rather a bit of lore or a folk saying about a plant. “Mustard, sunning in the field,” says one, “had for the winter blind that brilliant quality of flaming sun.” In Mellinger’s scholarly article about the plants of Southern Appalachia, she wrote that plants “are gathered and brewed into slightly invigorating teas which seem to hold some of the distilled essence of rain and sunshine and take on an affinity with earth and sky.”

Some of the cards have common plants, even ones considered invasive, pressed flat and Scotch-taped to them. There is a kudzu leaf, the leaf and flower of a dandelion, leaf of plantain. As I held the cards, tucked each back into its place, small bits of the plant material crumbled and fell onto the table or in the box, between the cards, miniscule gray-green flakes, like oregano spilled from a spice jar. Though all archives are vulnerable to the decay of time, these plant remnants made Mellinger’s collection seem particularly fragile.

But then, the archive is, mostly, plant material: the pulped wood of trees pressed into thin pages, inked with symbols made by the hands of the once-living for a future generation to read. And for most of written history, ink was made with walnuts, with oak galls. And the archives are stored within walls of wood: slices of the rings of trees, which are their own archives, dismantled so that they might house others.

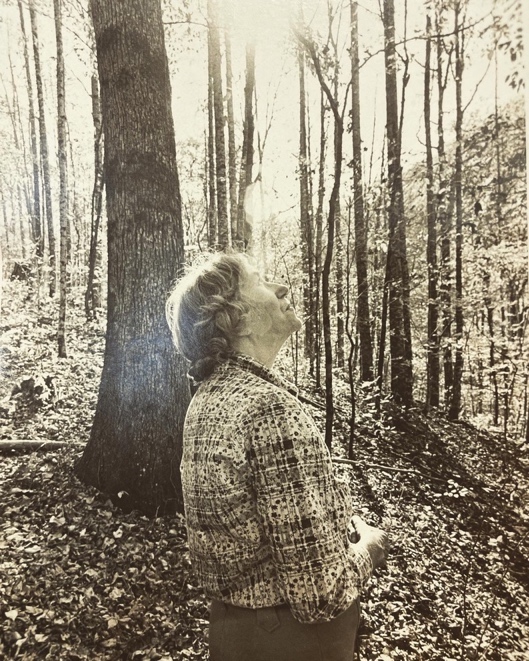

I came across a black-and-white photograph of Mellinger walking through the woods, her head lifted to the forest canopy, and imagined what flicker of wings she may have caught sight of there, how the trees house invisible archives of songs handed down generation after generation. I imagined the bubbling swirl of a cerulean warbler’s song. The light poured through the trees. The photograph did not indicate the photographer, but I imagined the person who was led by Marie that day through the woods and snapped her photo from behind—what plants they foraged, what meal they prepared later. Did they find a ruffled chicken-of-the-woods mushroom? Did they gather beech nuts? Did they stumble upon a lush growth of cress? A pawpaw growing on the creekbank?

In another photograph from a local newspaper, Mellinger walked in the lead with a group of people behind her, following along. Foraging walks were “the way for Mellinger to get her message across,” the caption read. Her message, in that particular article, was that she was worried “what the future holds in store” for her home. She worried about her home as archive, due to the lack of environmental education, the power company spraying pesticides, the Forest Service leasing land for timbering and extraction, the overdevelopment of her county.

Any meal can only be eaten once, as a man never steps in the same river twice, but this fact is particularly heightened by foraging. Every bite is the most potent imaginable distillation of the season, and each season lasts only a day. Every morsel is an unscrolling of the landscape in your mouth, the complex essence of the forest. You smell it, taste it, admire its color, its texture, hear yourself chewing it. It is the blossoming of a moment that now courses through your veins. It cannot be preserved, only savored as best as your senses will allow. To imprint this temporary, perishable earth into ourselves so deeply.

In the days after I visited the Mellinger collection, as March unfurled toward April, I roamed, my eyes turned down toward the ground, and up to the canopy. I saw the wild ginger growing and remembered last summer, when drought and heat had struck, and I fetched a bucket of water from the creek and poured it over the thirsty, wilting plants just feet away from the bank. The ginger had revived. I would not harvest it. In the field I saw dandelions, hundreds of small blazing suns, stars of the daytime that closed at night. I filled a bowl with them, and the rounded leaves of violet that were everywhere, and the long lance-shaped leaves of plantain, a plant brought by Europeans that spread so rapidly from areas where it was planted it was called “white-man’s footprint.” It is said to have gone westward ahead of white settlements, so that when it showed up, Indigenous communities knew that the colonizers would arrive soon. We forage from a cultural archive and eat from our legacies and lineages of relationship to the land. I will never taste an American chestnut. I will never dig a ginseng root. I eat what’s abundant, avoiding roadsides where herbicides are sprayed.

Ecology, the study of the oikos, is a study of relationships. It is the study of the complex web of home, its weave of stories, histories, and species. This, to my mind, is the great golden hive—this vast net of the world. The untraceable path of bee to blossom, the bee’s dance, the untold zillions of paths to nectar. The link from hop-hornbeam catkin to cerulean warbler, from chicken-of-the-woods mushroom to red-oak root, mycelial thread to beech grove, creek to cress, fungus to chestnut, chainsaw to ginger, mower to clover, individual to community, forest to frying pan, present to future, hand to earth, mouth to seed.

I sautéed the greens and made bite-sized pies with them. Three friends came over, and we ate them on the hillside in the late afternoon sun. It was dogwood winter, a cold spell, and we huddled together in our jackets, the chilling wind biting at our necks. We chewed, closed our eyes to taste the moment that was a season in itself—savored it, as best we could. To imprint such a perishable earth into ourselves so deeply.

Holly Haworth is an award-winning author whose work has been included in The Best American Science and Nature Writing and listed as notable in The Best American Travel Writing. She is a recipient of the Middlebury Fellowship in Environmental Journalism and has been nominated twice for a Pushcart Prize.