In the mid-nineteenth century, eastern Massachusetts was a hub for American horticultural talent, including writers and nursery owners. In the case of fruit breeders like Edward Staniford Rogers, even work conducted at a relatively small scale had the potential to spread nationally, shaping breeding efforts into the present. Rogers focused on grapes, and he did his work in his half-acre backyard at 376 Essex Street, in Salem, Massachusetts. Rogers came from a prosperous mercantile and shipping family, and in 1826, the year Rogers was born, Essex Street was one of Salem’s wealthiest residential neighborhoods. The street ran into the city’s center, near the wharves of Salem Harbor, then one of the busiest ports on the Atlantic seaboard.

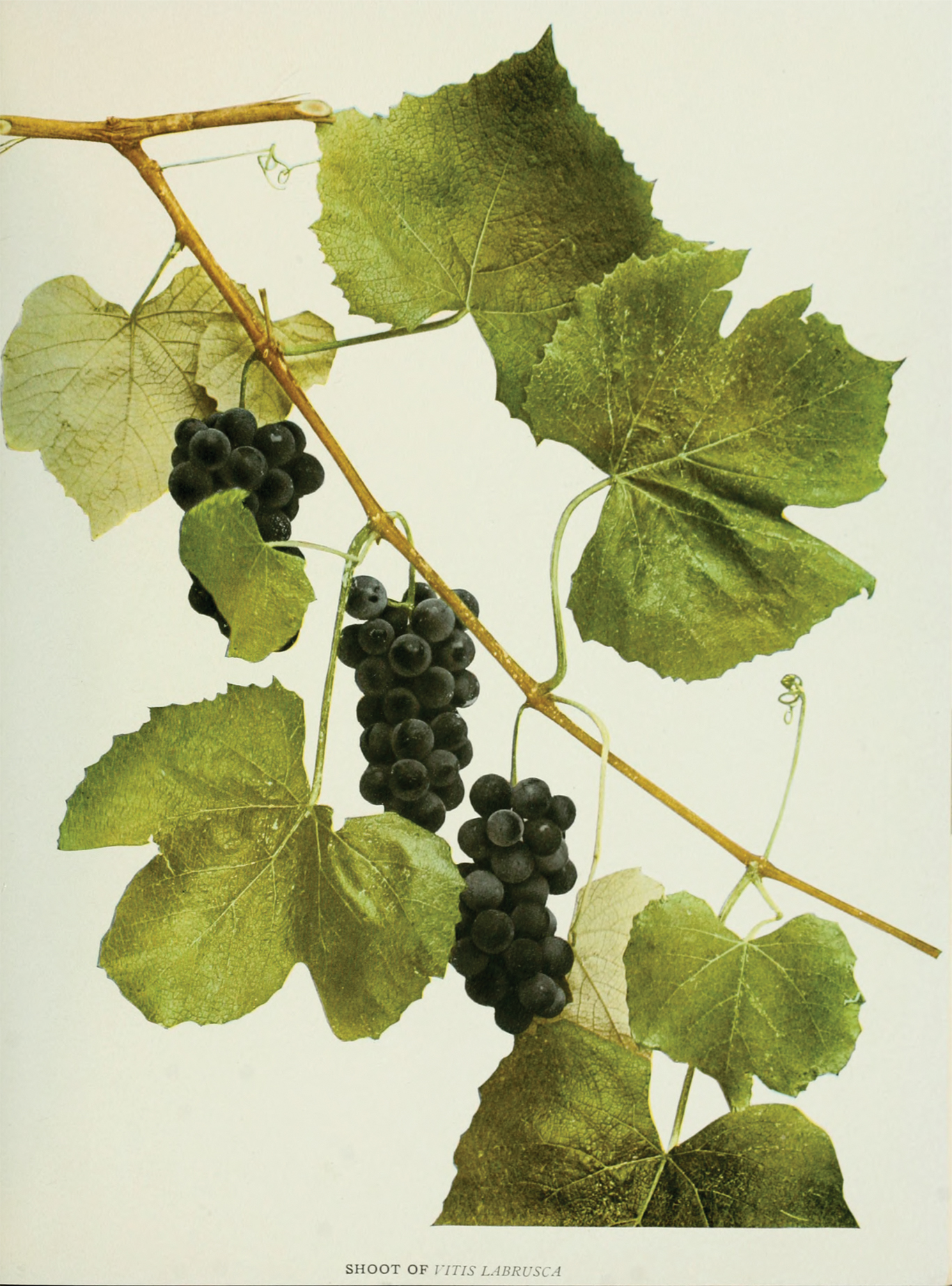

Rogers began his breeding work in 1851, when he was still a young man. While shy with most people—some would even say reclusive—he could talk endlessly about his new hybrid grape creations and did so regularly with local and nationally renowned horticulturists. In the process, he became a leading American grape breeder, focusing on hybridizing the common European grapevine (Vitis vinifera) with the hardier and more disease-resistant American fox grape (V. labrusca). Ulysses Prentiss Hedrick, the chief horticulturist of the New York State Agricultural Experiment Station, extensively wrote about Rogers’s work and noted, in 1908, that when Rogers introduced his grapes to the public in the late 1860s, “enthusiasm and speculation ran riot.” Another breeder, James H. Ricketts of Newburgh, New York, had released successful varieties around the same time, and it was, according to Hedrick, a “golden era” for American grapes. “Possibly at no other period has interest in grape-growing been so keen as during the decade succeeding the introduction of these hybrids,” he wrote.

A Horticultural Renaissance

As a grape grower and winemaker, I came to appreciate the landmark hybridization work of Rogers while researching and acquiring cool-climate grape hybrids that were developed in France between 1860 and 1940—primarily crosses between Vitis vinifera and American species like V. labrusca, V. aestivalis, V. riparia, and V. rupestris. I became attuned to these French-American grape hybrids starting in 1974, first by working at Benmarl Vineyards, in Marlboro, New York, and subsequently at the Hudson-Chatham Winery in Ghent, New York, where I encountered red grapes like ‘Baco Noir’ and ‘Chelois’ and white grapes like ‘Seyval Blanc’ and ‘Vidal’, along with more than a dozen others.

My interest then led me to Rogers and other East Coast hybridizers, including a significant number based in the Hudson Valley. I evaluated the Rogers varieties to see if they could be grown in a more ecologically sustainable manner than grape varieties that are conventionally grown today, and I wanted to learn more about the flavor profiles of these forgotten old varieties. For over fifteen years, I have grown twelve of these Rogers hybrids very successfully on my farm, Cedar Cliff, in Athens, New York, for wine production. It is my hope to reintroduce some of the Rogers grapes to commercial growers and wineries so that they can be made more readily available to the public.

In the process of researching heirloom grape varieties, I discovered that, between 1840 and 1890, eastern Massachusetts and the Mid-Hudson Valley were two of three centers of grape breeding. Breeders were also busy near St. Louis, Missouri. In Massachusetts, the breeders were generally wealthy New England Brahmins, like Rogers, whose families made fortunes either as merchants or in mercantile shipping. These genteel farmers engaged in horticulture for intellectual stimulation and social comradery. Nursery owner Charles Mason Hovey facilitated communication between nearby breeders and regularly corresponded with the national fruit-breeding community either in person or through the many plant catalogues, pamphlets, and horticultural books that he wrote. In addition, Hovey helped to direct, along with Marshall Pinckney Wilder, the nationally recognized Massachusetts Horticultural Society and the American Pomological Society. Local agricultural and horticultural societies were also actively evaluating new horticultural varieties in most eastern Massachusetts counties.

Several forces compelled these Massachusetts horticulturists to develop new hybrid fruit. Many desired to create plant material for their suburban and rural homes, emulating the British landed gentry and securing greater social prestige within their community. Others desired to develop fruits that were more productive and disease resistant for profit. An underlying theme was the uniquely New England quasi-religious-social-ethical belief among business, social, and religious leaders that one’s religious service could be manifest by service to community. Work had a moral component, and the highest calling was to be productive; unlike the trading of goods, engaging in agriculture and manufacturing was a divine calling.

Further, by 1800, the region’s already thin agricultural soils were becoming very depleted due to more than a century of extensive but unwise cultivation techniques and practices. Hence, a movement arose to study agriculture, hybridization, and plant sciences, so that local farmers could revitalize their increasingly poor and overcropped soils. The business community supported these agricultural research initiatives so that farmers would remain in Massachusetts and continue to be their loyal customers, instead of being forced to move farther west in search of more fertile soils. The business community’s support was evidenced by the founding of the Massachusetts Society for Promoting Agriculture in 1792. Its membership was clearly mercantile in composition, including most of eastern Massachusetts’s prominent families, along with attorneys and a few physicians and clergy, most of whom were Harvard College alumni.

Hybrid Crosses

Even within this vibrant horticultural milieu, Rogers was unique. According to Thomas Volney Munson, a central figure among the next generation of American grape breeders, Rogers was responsible for taking “the first intelligent step” towards developing “thorobred” American grape varieties. Unlike the classic ‘Concord’, which was selected by Ephraim W. Bull from a spontaneous cross between Vitis labrusca and V. vinifera (the results of natural insect pollination) in Concord, Massachusetts, in the 1840s, Rogers was intent on carefully making and documenting his crosses. In his own words, Rogers said, “When I commenced experimenting I had no knowledge of any one who had raised grapes by this process, though I had heard of flowers, pears, &c., and I had attempted crosses of pears. Reading articles in the London Horticulturalist, it occurred to me that I could get a new grape by this process; combining the qualities needed for open culture, it would be more valuable than any other fruit.”

Rogers was drawn to the quiet and contemplative life of horticulture, and once his father died in 1858, he very quickly exited the family shipping business and concentrated on his horticultural pursuits and real estate investments in Rockport, Massachusetts. He wanted to create new grape varieties that incorporated the more sophisticated and subtle flavors of European Vitis vinifera varieties (like the table grapes we buy today in the supermarket) with the hardiness and reliable productivity of native American grape varieties, ripening early, before the first fall frost. Successful varieties also needed to possess ample fungal disease resistance and simultaneously be productive enough as commercial table grapes, with big berries, big clusters, sufficient sweetness, and skin that adhered to the flesh of the berry.

In the summer of 1851, Rogers made crosses using a seed parent, Vitis labrusca ‘Carter’ (a wild-type variety also known as ‘Mammoth Globe’), and the pollen of V. vinifera ‘Black Hamburg’ and ‘White Chasselas’. ‘Carter’ was used as the seed parent because this self-sterile variety was large fruited, hardy in the field, and one of the earliest ripening local selections that he could find. The pollen of ‘Black Hamburg’ and ‘White Chasselas’ was chosen because they were two of the hardiest European varieties and were the most commonly available in Massachusetts. The pollen was obtained from vines growing in a nearby unheated glass greenhouse. The exact provenance is unrecorded, but the pollen could have come from someone like John Fisk Allen, who lived about two blocks from Rogers, or George Haskell, in nearby Ipswich. Both men were highly interested in grape cultivation.

The ‘Carter’ blossoms were emasculated and fertilized with Vitis vinifera pollen and small cotton bags were placed over the ‘Carter’ female flowers. Rogers also placed clusters of V. vinifera blossoms in the bags. From this cross-pollination, he secured about 150 seeds. These seeds were then planted in his backyard garden that fall. The following spring, many of these seeds germinated, but cut worms and other accidents reduced the number of vines to forty-five. These forty-five vines grew upward on poles for three years. Due to overcrowding, Rogers transplanted twenty-five of the plants to other parts of the garden to give them enough room to grow. The untransplanted vines started to bear fruit in 1856, and the transplanted varieties fruited a few years later. In observing the garden, Marshall Pinckney Wilder, of the American Pomological Society, said, “How much can be done with little is illustrated by the fact that all [of his grapes] … were produced by a lame man in a half-acre city lot 150 years in cultivation.” Further, he noted that the lot was “a cold matted soil filled with old apple and pear trees, currant bushes, flax and everything mingled in together.”

Rogers believed his grape creations to be a success, noting the intermixture of traits between the species. “The vines are even more vigorous than the parents,” he wrote, “and more exempt from diseases, and more hardy than most out-door varieties.” The seedlings were numbered one to forty-five. In 1858 and 1859, Rogers sent cuttings of these numbered varieties to growers and horticulturists for further testing. He disseminated these varieties due to the small size of his backyard garden and because the common practice then, as it is now, was to share plant material with colleagues to get comments on the growing attributes, strengths, and weaknesses of such plants in a wide range of climates and soil types.

Through his painstaking work, Rogers created over twenty major grape hybrids. The resultant grapes were first officially introduced to the public in 1867. In 1869, Rogers named thirteen of his varieties after local Massachusetts places and people (‘Agawam’, ‘Massasoit’, ‘Salem’, ‘Essex’, and ‘Merrimac’), as well as for horticulturists (‘Barry’, ‘Lindley’, ‘Gaertner’, and ‘Wilder’) and the German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (‘Goethe’). These were promoted through the Catalogue of Fruits by the American Pomological Society, an organization that was based in Boston. From there, the Rogers hybrids steadily gained interest and notoriety across the United States and Canada.

The Rogers Grapes

All Rogers hybrids possess large or very large berries, medium-sized clusters, and grape skin that is either attached or semi-attached to the berry flesh, unlike the “slip-skin” characteristic of the ‘Concord’. They grow vigorously, have better fungal disease resistance than their European pollen parents, and are hardy and productive. I like the growing characteristics of the twelve Rogers hybrids that I cultivate in the Mid-Hudson Valley, and the resultant fruit is flavorful and makes wonderful wines that have an attractive combination of soft flavors of Muscat grapes and Vitis labrusca.

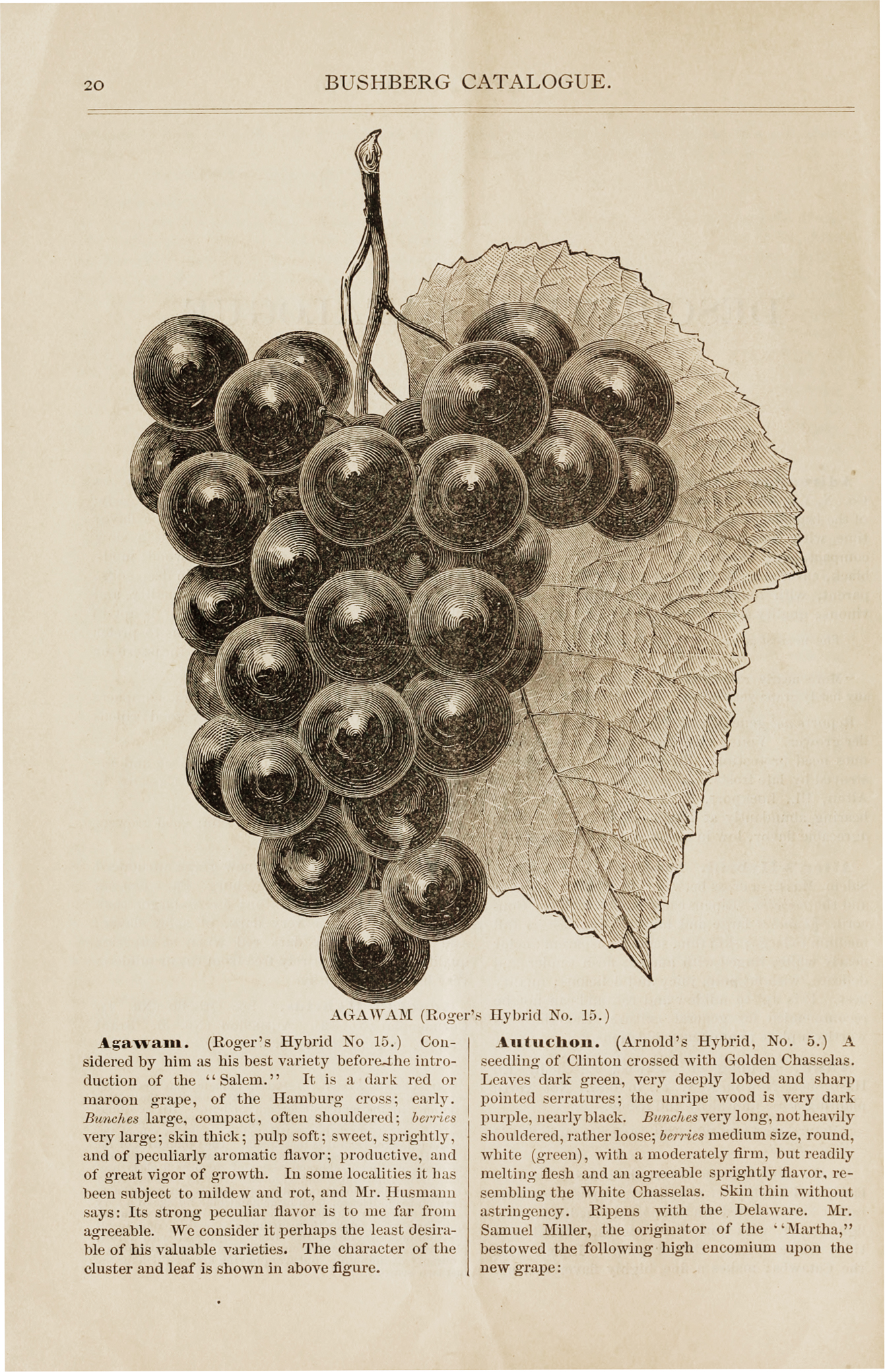

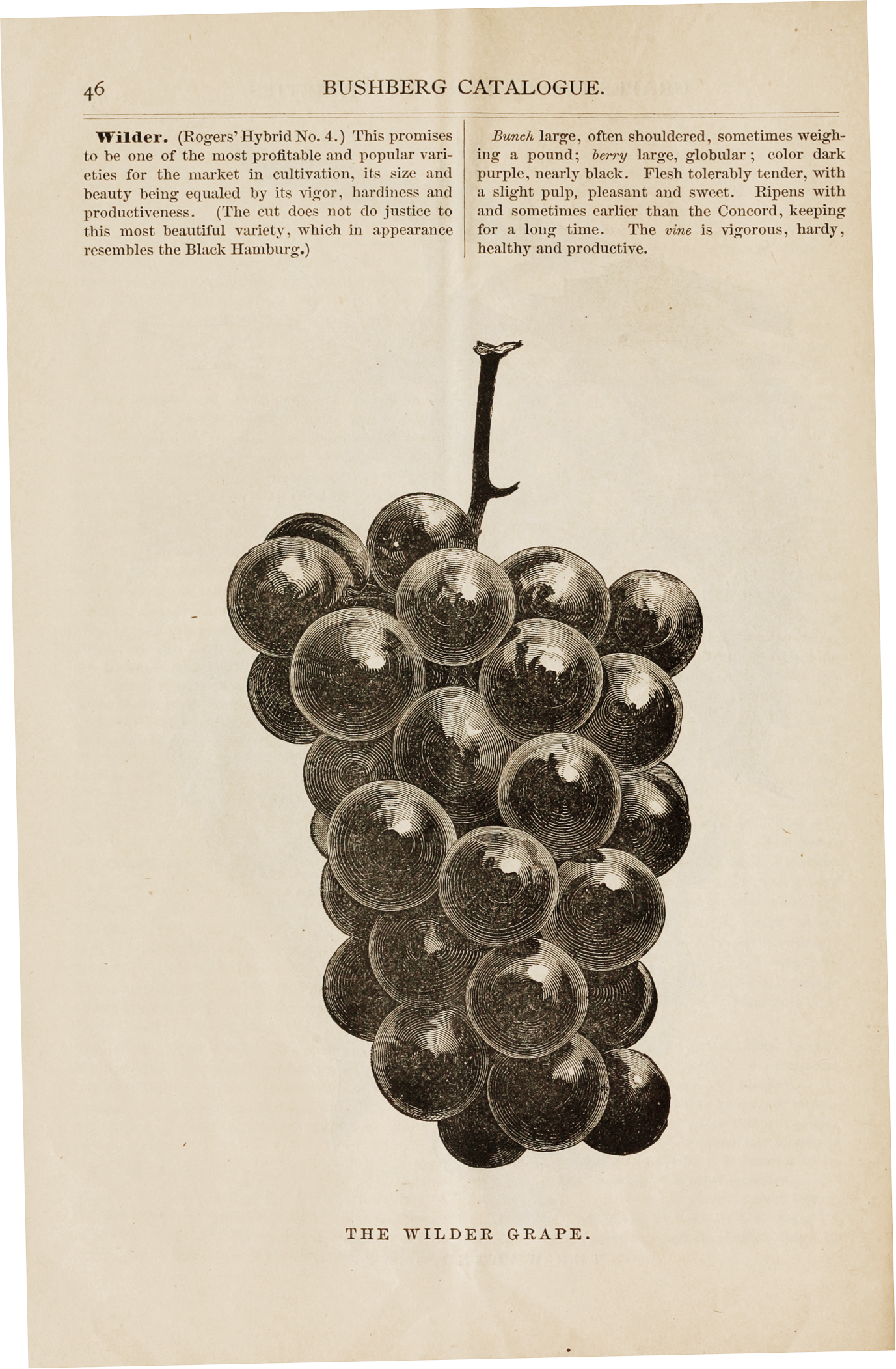

These characteristics made the Rogers hybrids very popular when first introduced to America and Canada in 1867. They were initially quite sought after by growers, talked about at horticultural and agricultural society meetings, and widely evaluated. In 1895, the nationally recognized Bushberg Vineyards catalogue, which set the standard for fruit catalogues and pomological literature in North America, extensively covered the Rogers hybrids with accompanying illustrations of many of them. The Bushberg catalogue stated that these Rogers varieties were “very productive,” “beautiful,” and “valuable” selections that were “handsome in appearance” and of “fine quality” for the table and for wine. Other definitive North American nursery catalogues of the latter nineteenth century, including Hovey’s The Magazine of Horticulture, prominently featured and illustrated the Rogers hybrids, as did agricultural magazines like The Gardner’s Monthly and Horticulturist, The Rural New Yorker, and The Country Gentleman.

Among Rogers’s selections, ‘Agawam’ is one of his best. In 1908, Hedrick reported that ‘Agawam’ was the most widely grown of the Rogers hybrids, noting that it was sold by practically all nurseries in the United States east of the Rocky Mountains. It is the only completely self-fertile of the Rogers varieties. The color is a dark purplish-red with a lilac bloom. The wines are aromatic with rich fruit flavors of Muscat grapes and hints of fresh grapes, guava, and tropical fruits from Vitis labrusca, along with an herbal finish. The body is substantial and viscous for a white wine, and it can either stand alone or be used in blends with other white wines. Tasting something like this is to taste the nineteenth-century innovation of Rogers and his contemporary fruit breeders in Massachusetts, the Mid-Hudson Valley, and the St. Louis area.

The Rogers Hybrids Live On

A combination of factors led to dwindling name recognition for the Rogers grapes. Hedrick stated that the period between 1853 (the date ‘Concord’ was first introduced) and 1880 could be “singled out as the period in which viticulture made its great growth in eastern America.” After 1880, however, California started to compete in earnest with eastern vineyards, and grape prices fell significantly in eastern metropolitan markets, given the vast influx of inexpensive California grapes. This competition, combined with higher incidence of fungal diseases and insect damage in eastern vineyards, which were planted too closely to one another, severely reduced overall production in the east. With a corresponding reduction of grape acreage, varieties like ‘Concord’, ‘Niagara’, and ‘Delaware’ expanded their dominance, while the Rogers hybrids, which, save for ‘Agawam’, were mostly self-infertile, declined relatively and absolutely in acreage. In addition, the enactment of Prohibition in 1920 further reduced their demand for wine production, which was their primary use.

Yet the Rogers hybrids live on in the twenty-first century. In the Rogers era, privately organized horticultural and agricultural societies, such as the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, sponsored the bulk of the public discussion about plant evaluation. However, with the Congressional enactment of the Morrill Act of 1862 (establishing agricultural land-grant colleges) and the Hatch Act of 1887 (establishing agricultural experiment stations), this horticultural domain shifted increasingly to government-financed programs. With this shift, many of the Rogers grapes were incorporated into the most advanced American cool-climate, wine-grape breeding programs of the twentieth century. For example, at Cornell University, the Rogers hybrid ‘Herbert’ was used to breed the hybrids ‘Sheridan’, in 1921, and ‘Buffalo’, in 1938. These, in turn, lead to the development of twenty-first-century introductions like ‘Geneva Red’, ‘Corot Noir’, and ‘Noiret’. Elmer Swenson of Wisconsin, whose private breeding program was subsequently absorbed into research at the University of Minnesota, used the Rogers variety ‘Wilder’ as a great grandparent to create ‘Marquette’. The varieties ‘Marquette’ and ‘Noiret’ are now finding their place in today’s North American cool-climate wine industry. In addition, Rogers varieties were used in the breeding programs at agricultural experiment stations in Missouri and South Dakota. Thomas Volney Munson, the pioneer American grape breeder who privately bred many scores of high-quality hardy and disease-resistant grape varieties for the central and southern United Sates, relied heavily on Rogers hybrids for his extensive breeding program.

The Rogers varieties do not simply persist as the basis for subsequent breeding efforts. The variety ‘Goethe’ is the foundation of one niche segment of the Brazilian wine industry in the Urussanga region of the state of Santa Catarina. In Brazil, ‘Goethe’ is made mostly into sparkling wines with vineyards that cover over one hundred acres. While ‘Goethe’ is traditionally a pink-red variety, a natural mutation, first observed in a Brazilian vineyard the 1950s, has produced a white clone, now known as ‘Goethe Primo’. This new variety makes still and sparkling wines that are very Vitis vinifera-like in their flavor profile and acid balance but with pleasant, soft aromatics from V. labrusca. In this region, over twenty thousand gallons of ‘Goethe’ wine are produced, with the remainder sold as table grapes.

Today, commercial and hobbyist growers, foodies, farm-to-table advocates, private grape breeders, and university breeding and agricultural research programs are all looking for the “next best” fruit variety that is flavorful and productive and which can be grown in a more environmentally sustainable manner. The Rogers hybrids, along with other heirlooms bred in New England and in the Hudson Valley, fit that bill. Rogers’s work demonstrates that sometimes the search for the “next best” may involve looking back.

References

Bush & Son & Meissner, Bushberg Vineyards. 1895. Illustrated descriptive catalogue of American grape vines (4th ed.). St. Louis: R. P. Studley and Co.

Casscles, J. S. 2015. Grapes of the Hudson Valley and other cool climate regions of the United States and Canada. Coxsackie, NY: Flint Mine Press.

Cedar Cliff Nursery. 2013–2019. Cedar Cliff Nursery: Grape vines for grape growers and field & cellar notes. Catskill, NY: Casscles, J. S.

Downing, A. J., and Downing, C. 1869. The fruits and fruit trees of America (2nd ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Hedrick, U. P. 1908. The grapes of New York (Annual report of the State of New York, Department of Agriculture; no. 15, v. 3, pt. 2). Albany, NY: J. B. Lyon Company.

Hedrick, U. P. 1933. A history of agriculture in the State of New York (The New York State Agricultural Society). Albany, NY: J. B. Lyon Company.

Hedrick, U. P. 1950. A history of horticulture in America to 1860. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hedrick, U. P. 1919. Manual of American grape-growing. New York: The Macmillan Company.

Hovey, C. M. The magazine of horticulture, botany, and all useful discoveries and improvements in rural affairs. Boston: Hovey and Co.

Hutchinson, B. J. 1980. A taste for horticulture. Arnoldia, 40(1): 31–48.

McLeRoy, S., and Renfro, R. E. 2008. Grape man of Texas: Thomas Volney Munson and the origins of American viticulture. San Francisco: The Wine Appreciation Guild.

Morton, L. T. 1985. Winegrowing in eastern America: An illustrated guide to viniculture east of the Rockies. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Munson, T. V. 1909. Foundations of American grape culture. New York: Orange Judd Company.

Parker, S. J. 1865. Improvement of native grapes by seedlings and hybridization. In Report of the Commissioner of Agriculture for the Year 1864 (pp. 122–136). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Citation: Casscles, J. S. 2019. E. S. Rogers and the Origins of American Grape Breeding. Arnoldia, 77(2): 30–39.

Rogers Family Papers, Peabody Essex Museum (MSS 87). Phillips Library at the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts.

Schofield, E. A. 1988. “He sowed; others reaped”: Ephraim Wales Bull and the origins of the ‘Concord’ grape. Arnoldia, 48(4): 4–15.

Thorton, T. P. 1989. Cultivating gentlemen: The meaning of country life among the Boston elite, 1785–1860. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Wagner, P. M. 1969. American wines and wine-making. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

J. Stephen Casscles comes from a fruit-growing family rooted in the Hudson Valley since the 1870s. In 1990, he established a four-acre vineyard, Cedar Cliff, in Athens, New York, where he has concentrated on identifying, growing, evaluating, and propagating heirloom grape varieties that were first developed in New York in the mid-nineteenth century. He has been the winemaker at Hudson-Chatham Winery, in Ghent, New York, since 2008. In 2015, he published a book on historic grape cultivation titled Grapes of the Hudson Valley and Other Cool Climate Regions of the United States and Canada with Flint Mine Press.