KOREA, REPUBLIC OF –

WILSON, E. H. 11245

In 1918, Arboretum plant collector E.H. Wilson stumbled upon an interesting silk tree in a Korean hotel courtyard. Few thought this species could survive New England’s bitter winters, but Wilson collected seeds regardless. Surpassing expectations, one of that tree’s unique offspring now resides in our Explorer’s Garden, now over a century old—and still growing.

In 1918, plant collector Ernest Wilson and his family returned to the Korean Peninsula. Wilson was in the middle of a three-year plant collecting expedition, acquiring seeds and small plants for the Arnold Arboretum. During his family’s stay at the Chosen Hotel in Seoul, Wilson observed an unusual silk tree in the courtyard garden. Although this species is common in warm climates across Asia, he had seen none growing in cooler, central Korea. He gathered seeds, hoping that this individual might yield offspring similarly suited for chilly New England winters.

Wilson’s hunch paid off. In 1923, horticulturists planted a small sapling grown from these seeds in the Arboretum’s Explorer’s Garden. Expectations must have been low, as earlier attempts at growing silk trees at the Arboretum had ended in failure. However, this one survived. A surprised Wilson declared it “astonishing that this tree should be able to withstand New England winters.” That sapling is now over a century old, unprecedented for a species with a typical lifespan of just a few decades.

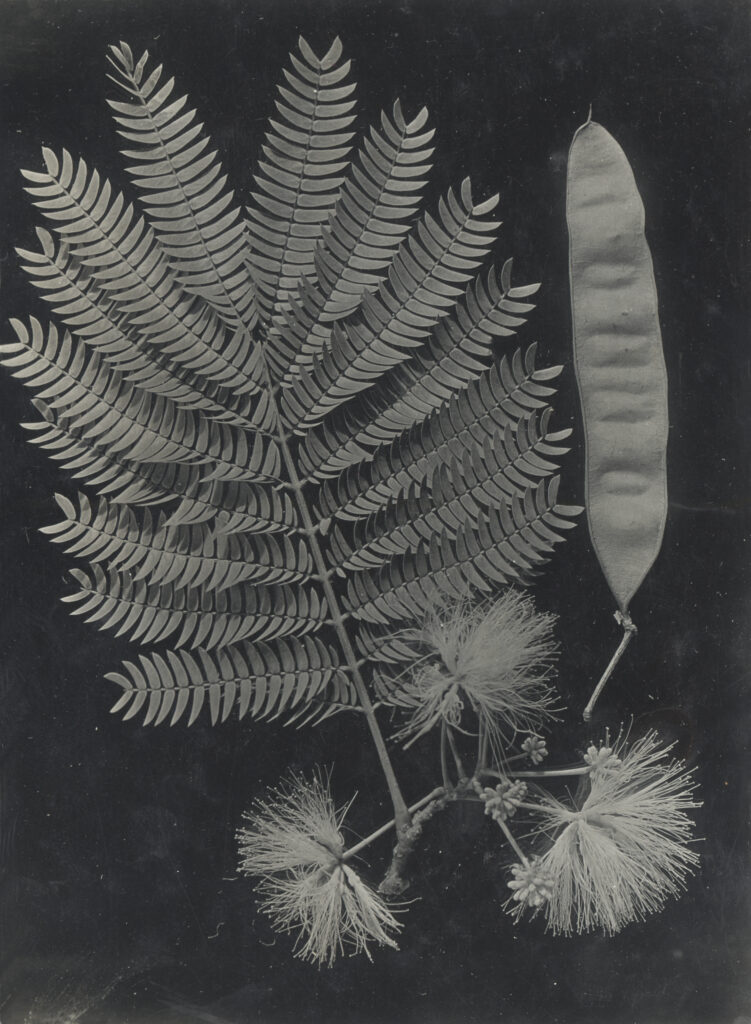

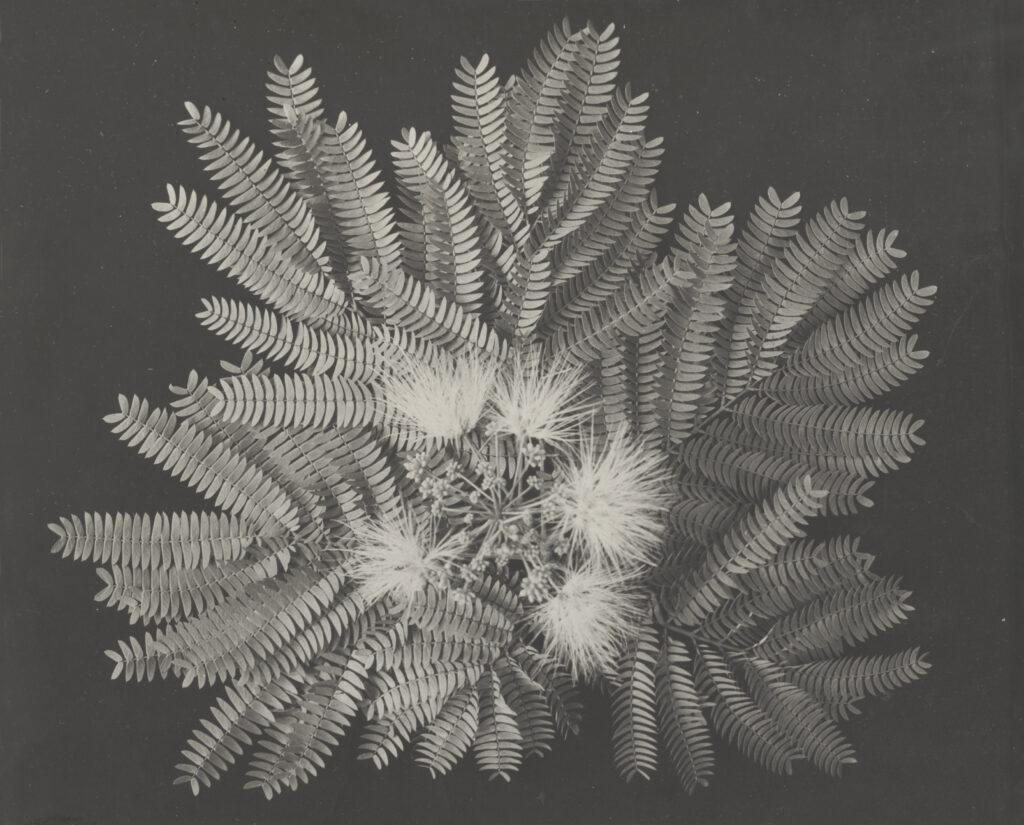

Cold tolerance and longevity turned out to be just two of this silk tree’s unique features. Unlike other specimens, Wilson’s introduction is shorter in stature, with a low hanging canopy. The tree also boasts stunning, bright pink floral highlights of a much richer hue compared to others. In 1968, the Arboretum named this distinctive silk tree cultivar Albizia julibrissin ‘Ernest Wilson’, in honor of his contributions.

This globe-spanning success story exemplifies the Arboretum’s renowned history of plant exploration and introduction. However, in some ways, it is also emblematic of a Western-centric chapter of plant collecting. The hotel courtyard garden origin of the mother silk tree implies that Korean horticulturists perhaps intentionally selected it for cold tolerance. Modern sensibilities suggest honoring the Koreans who at some point began the cultivation process (and cared for the tree he collected from) rather than Wilson alone.

Cultural changes apply to plant collecting methods as well. Although once an extremely fashionable garden addition, particularly in Europe and the American south, the silk tree quickly escaped cultivation. Today, many southern and south-western US states categorize the silk tree as an invasive species. Although not considered invasive in Massachusetts, Arboretum staff nonetheless learned from the example of other invasives that did take hold. Present-day plant collectors carefully consider invasive potential before introducing new species into our landscape. Importing foreign species and seeds is also now strictly regulated by the U.S. government.

In any case, the Arboretum’s six silk trees (including two specimens of the Wilson cultivar) serve a valuable function in our living museum. During cold winters, blanketed thick with winter snow, they teach us valuable lessons about biological adaptation, horticultural ingenuity, and global plant collecting. Late summer afternoons, on the other hand, offer a moment for philosophical musing. On these days, our silk trees’ pink and white flowers attract crowds of visitors and staff expressing admiration and, sometimes, disdain. As the wind blows, you can almost hear the silk trees talking as well, about the mysterious human love for plants, the fascinating complications of our desires.

South Korea

Viewing this plant in-person? Look for these defining characteristics:

1

2

3

4

5

About Our Collection

Fun Facts

Stats

- Living Specimens

- Specimens Dead or Removed

- First Addition

- Most Recent Addition

- Tallest Specimen

3 Living Specimens

| Plant ID | Accession Date | Received As | Origin | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|