‘Dunfee’ Highbush Blueberry

Vaccinium corymbosum ‘Dunfee’

- Accession Number

- The alpha-numeric value assigned to a plant when it is added to the living collection as a way of identifying it.

- Accession Date

- The year the plant’s accession number was assigned.

- Common Name

- The non-scientific name for the plant.

- Scientific Name

- The scientific name describes the species of an organism. The first word is the plant's scientific genus and the second is the specific epithet. This two-word binomial is sometimes followed by other taxonomic descriptors, including subspecies (denoted by "ssp."), variety (denoted by "var."), form (denoted by "f." or "forma"), and cultivar (denoted by single quotation marks).

- Plant Family

- The family to which the plant belongs.

- Propagation Material

- The first part (material code) describes the material used to create the plant. The most common codes are "SD" (seed), "EX" (existing plant), "PT" (plant), "CT" (cutting), "SC" (scion), "SG" (seedling), and "GR" (graft). The second part describes the lineage the plant is derived from. The last part describes the year of propagation.

- Collection Data

- The first part indicates provenance (place or source of origin) using a letter code ("W" = wild, "G" = garden, "Z" = indirect wild, "U" = uncertain). The second part lists the plant source. For wild-collected material, the collector, collection number, and country are given.

- Location

- The location of the plant on the landscape.

UNITED STATES -

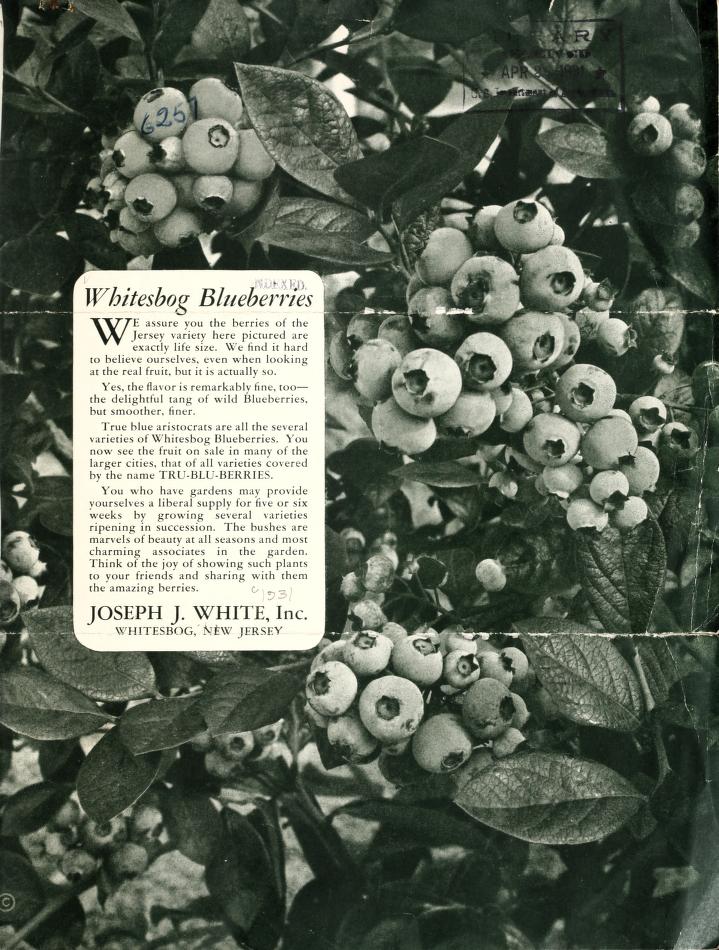

JOS. J. WHITE, INC.,

NEW JERSEY, U.S.A.

It took a village to tame the wild blueberry.

Along the Arboretum’s Meadow Road grows a highbush blueberry discovered by a ten-year-old boy. Highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum) is the same type of blueberry available in our grocery stores. However, before 1916, it could only be found in the wild. In 1916, USDA botanist Frederick Coville and cranberry farmer Elizabeth White, of Whitesbog in Browns Mills, NJ, did what scientists and farmers nationwide had been unable to do for decades: they brought to market the first blueberries grown agriculturally. The ‘Dunfee’ highbush blueberry shrub on Meadow Road was instrumental to that achievement.

Wild high- and lowbush blueberries (V. angustifolium) flourished near Coville’s New Hampshire farm, yet most attempts to cultivate them had failed miserably. Intrigued, Coville began a series of experiments to learn more, publishing his findings in a 1910 article titled “Experiments in Blueberry Culture.” One of his key discoveries was that, unlike most agricultural crops, blueberry plants thrive in acidic soils—the same type of soil in which cranberries (V. macrocarpon) flourish.

White likely leapt out of her chair upon reading this. For years, she and her father, Joseph White, had dreamed of cultivating blueberries on their farm. Wild highbush blueberries (also called swamp huckleberries) grew abundantly around Whitesbog, offering a delicious treat when the fruits ripened in summer. If they could be tamed, they would make the perfect complement to the autumn cranberry harvest and provide a longer work season for the Whitesbog pickers.

Immediately, White wrote to Coville offering encouragement and support. Their collaboration began in 1911. White provided choice wild specimens; Coville did the breeding work, developing methods of propagation that are still used today; and when seedling plants were ready for the field, White provided testing fields with ideal soil and experienced caretakers at Whitesbog.

Since large berries would be easy to pick rapidly and catch the consumer’s eye and interest, largeness of the berries was the only consideration in selecting the first wild specimens. With a nod to their knowledge of the Pine Barrens, White enlisted her neighbors’ assistance, offering up to $3 per bush to any local picker who located a plant with at least one fruit measuring 5/8th of an inch or more. At first, the bar was set at ½ an inch, but such fruit was so easily found that the standard was quickly raised.

White and Coville were surprised to receive, in just three to four years, no fewer than one hundred bushes that met the higher 5/8th inch standard. Among them was a bush found by a boy named Theodore Dunfee, who was quite tickled to have found a qualifying specimen. After plants grown from these wild collections were studied under field culture, Vaccinium corymbosum ‘Dunfee’ (White named the first several plants after their finders) earned the further distinction of being one of only six varieties out of the hundred “considered worthy of further multiplication for commercial fruit production.”

Of the seven named cultivars (cultivated variety) of highbush blueberry sent by J.J. White, Inc. to the Arboretum, the ‘Dunfee’ along Meadow Road is the oldest remaining. After one hundred years in Arboretum soil, it is still looking as spry as the young boy whose name it bears.

New Jersey

Viewing this plant in-person? Look for these defining characteristics:

About Our Collection

Fun Facts

Stats

- Living Specimens

- Specimens Dead or Removed

- First Addition

- Most Recent Addition

- Tallest Specimen

Living Specimens

| Plant ID | Accession Date | Received As | Origin | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|