Explore past offerings using the links below

2019: Tree habit | Science in the schoolyard | Learning through flower dissections | Learning about conifers

2018: Impressions from a visiting professor | Spring marches on, despite snow | Tree architecture primer

2017: Teachers search for tree bark | Investigating winged seeds | Exploring freshwater habitats | Searching for signs of spring | Boston teachers learn how to read twigs

Tree habit

December 10, 2019 | By Ana Maria Caballero, Nature Education Specialist

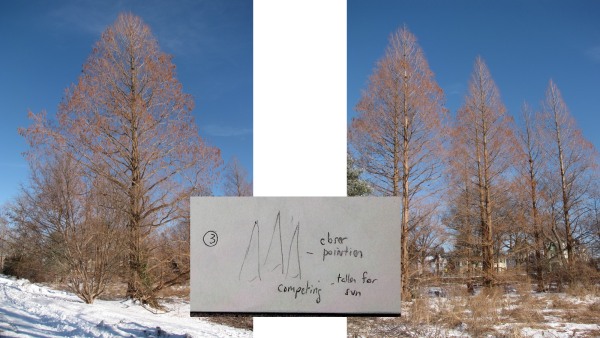

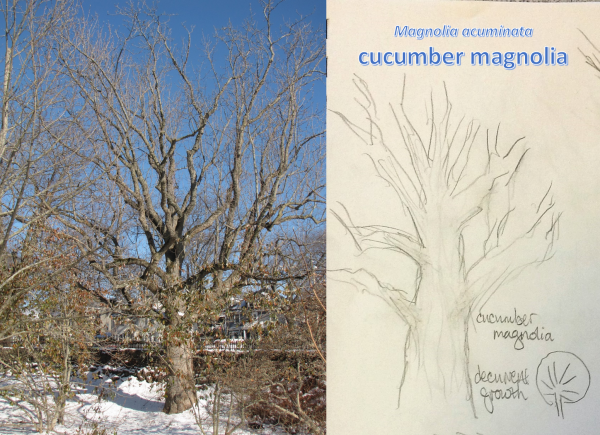

Sometimes trees get a bad rap. There’s the Whomping Willow of Harry Potter fame, the trees in Snow White’s terrifying Dark Forest, and our very own cucumbertree (Magnolia acuminata, 15154*D), which was recently described as grumpy, gnarly, and foreboding by several participants of Saturday’s Arboretum for Educators program. The topic was tree architecture and the goal to closely observe the growth habit of various trees at the Arboretum in order to discern some environmental factors that might be influencing specific forms. These observable characteristics comprise the phenotype of a tree, as opposed to the genotype, which is determined by its genetics or DNA.

By visiting pairs of the same tree—each growing under very different conditions—participants were able to understand how stark differences in phenotype can occur. For example, the cucumber tree located near the Arborway has plenty of access to light, space, water, and nutrients. Its massive form is a great example of a decurrent (rounded or spreading) growth habit. By contrast, an individual of the same species (49-2014*A) located on the slope behind the Hunnewell Building is somewhat crowded and shaded by neighboring white pines and exhibits excurrent (irregular or cone-shaped) growth as it reaches for the light before branching out to expose leaves to the sun.

One powerful way to observe tree shape is by creating quick “gesture” sketches of trees in about 30 seconds. This allows the eye to focus on the most prominent forms, relative positions, and size of tree branches. With children, one could add the step of using the body to form the target shape and connect language to what is being observed.

Another way to understand why trees have specific shapes is to learn about the physical arrangement of terminal buds, lateral buds, leaf scars, and terminal bud scale scars on a twig. A tree twig that has opposite leaf buds and clusters of buds on the tip (red maple, Acer rubrum) will develop differently, and therefore be shaped differently, than a twig with a large sticky terminal bud and alternating leaf buds (horsechestnut, Aesculus). When observing and drawing twigs, it is best to use a hand lens and large paper in order to capture details on a life-size scale. Children can even be encouraged to trace the shadows of the twig when drawing under a strong light to jumpstart the drawing process.

Understanding why trees are shaped the way they are can go a long way to changing a tree’s bad rap!

The Arboretum for Educators events aim to introduce seasonal, natural phenomena to teachers and model ways in which students can engage in outdoor learning. Programs are designed to illustrate how teachers can bring that learning back to their classrooms for further investigations.

Science in the schoolyard

May 28, 2019 | By Ana Maria Caballero, Nature Education Specialist

More than a dozen Boston Public School teachers and area educators participated in a two-day professional development institute hosted by the Arnold Arboretum and the Museum of Science, in collaboration with the Friends of the Boston Schoolyards. Science in the Schoolyard—Teaching Science Standards With Outdoor Spaces aimed to help teachers see the power of outdoor learning. Together we examined curriculum and practices that nurture student relationships to the natural world and experimented with these in two BPS schoolyards: the Mission Hill K-8 School and Dante Alighieri Montessori School.

The Arnold Arboretum hosted educators on Saturday, May 4. Ana Maria Caballero, Nature Education Specialist, began with a presentation of four essential science practices that allow students to “learn science by doing science.” Using the landscape for inspiration, teachers encountered complex phenomena, first indoors through a set of prepared materials at stations, and then outside in a free exploration of the wetlands, lawns, and woods around the Hunnewell Building. How does a drop of water behave on the surface of a leaf? What explains the veined remains of a leaf during decomposition? How can we explain the seemingly different shaped leaves found at different heights of the same holly plant? These and other phenomena spurred teachers to wonder, make claims, and use evidence to support their thinking.

Earth science, physical science and life science standards can all be addressed in outdoor spaces and schoolyards. Armed with copies of the Massachusetts Science Technology and Engineering standards and the Science and Engineering Practices, teachers began to brainstorm ways in which natural outdoor settings can help engage children with specific topics, or be useful for elaboration and even assessments of classroom based learning. For example, by observing the way a cultivar of Fortune’s spindle tree (Euonymus fortunei ‘Coloratus’; 21105*MASS) from 1930 is growing alongside a red maple (Acer rubrum ‘Schlesingeri’; 3256*A) from 1888, teachers began to wonder how one plant affects the other, whether the hole inside the maple was caused by the vine, which roots belong to which plant, and what type of symbiosis this illustrates. As is usual in science, there were many more questions than answers!

On Saturday May 18, teachers gathered at the Museum of Science to work with teacher educator Meredith Mahoney and learn from a few carefully selected exhibits to address topics in physical science and life science. A simple activity involving balls and a hula hoop, with minimal directions, allowed teachers to explore concepts related to forces and motion, and consider many variables when setting up experiments. This conversation continued as teachers then engaged with Science in the Park, an exhibit that uses playground equipment and familiar objects to investigate the pushes and pulls of everyday life. Teachers then were encouraged to play with materials and create a game or model that could be used to teach various physical science concepts.

A second area of learning at the Museum of Science involved visiting the Butterfly Garden, insect exhibit and bee hive. Teachers observed various insects in a natural setting, examining their body parts and behavior. This close observation of natural phenomena led to interesting questions—do bees ingest pollen and nectar for their own sustenance? What is used to make the honey in the hive? What are butterfly scales really like? How long is the proboscis? This type of scientific curiosity is exactly what we want for all students and using the outdoors for science learning is a natural conduit to achieving these results.

On both days, the afternoons were spent visiting the different outdoor spaces of the Mission Hill and Alighieri Schools, analyzing places within that would lend themselves to all manner of scientific investigations. This allowed teachers to get inspiration from different outdoor spaces, imagine how their own schoolyards could be sources for authentic science learning, and inspired them to envision scenarios where students are actively using science practices to make sense of their experiences within outdoor spaces. This goal is also shared by the Friends of the Boston Schoolyards, an organization which actively promotes the use of beautiful outdoor classrooms and play spaces found within many of the Boston Public Schools for academic, social, and emotional learning.

If you are interested in this topic of outdoor education, join the Arboretum for Educators on June 1, or during the next academic calendar starting in October 2019. Together, we work to support life science teaching and learning using the outdoors.

Learning through flower dissection

April 11, 2019 | By Ana Maria Caballero, Nature Education Specialist

Last Saturday teachers participated in the Flower Dissection program of the Arboretum for Educators, a monthly program aimed at helping teachers learn more about using the natural world for purposeful science learning. This particular class followed the 5E Instructional Model, both as a way to learn new teaching strategies and to experience what it is like to construct new ideas from previous ones. In this model, the phases of learning are Engage, Explore, Explain, Elaborate, and Evaluate. A daffodil served as the model flower for teachers to dissect and around which experiences were built. Below is a snapshot of the model in action.

Engage:

Here are two ways students can be drawn into a study of flowers: “What is a flower for? Discuss with a partner” or “Draw a flower from memory and label what you know.” In both cases, teachers are looking to elicit background knowledge and perhaps illuminate misconceptions that students may have around this topic. By listening carefully and asking probing questions, a teacher can gather a lot of information that can be addressed during the rest of the study.

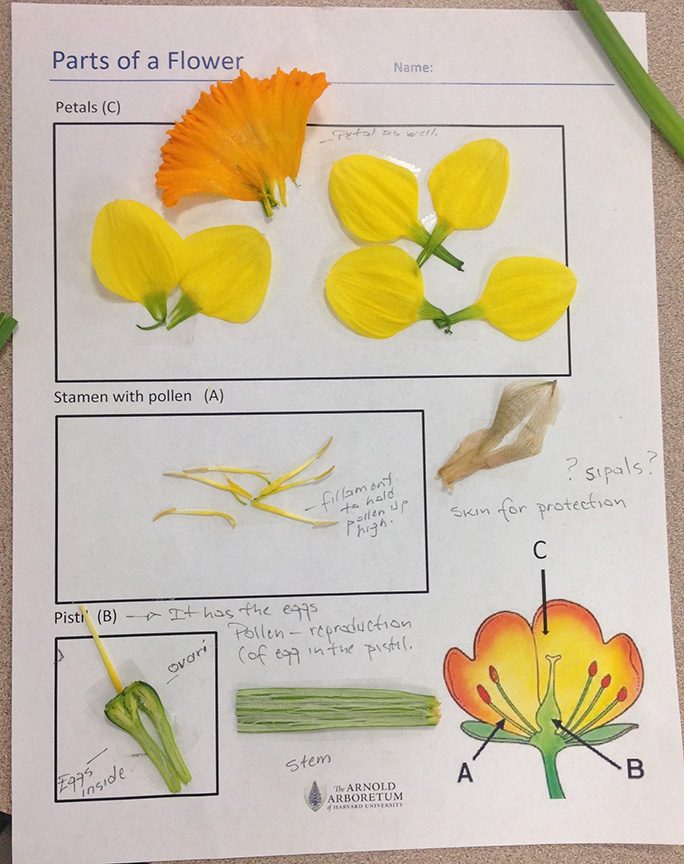

Explore:

Ample time should be allowed for students to examine a flower using a hand lens or to make an observational drawing, along with a guided dissection. Students should be guided to take petals apart and view them under stereo microscopes, then progress from the outside in, examining the stamen, pistil, and ovary of the daffodil. Labeling flower parts should be kept to a minimum; rather, students should focus on form and hypothesize about each part’s function, providing a clear reason for their claims. Providing students with additional tools such as visual organizers, black chenille stems (to collect pollen), and T pins can facilitate more discovery and better ways to interact with the flower parts.

Explain:

This phase allows a teacher to help students connect their thoughts and discoveries with facts. Provide a labeled flower diagram so students can review their notes or drawings and add the correct vocabulary. Pose questions to highlight the location of the flower parts in relation to the whole, and explain the process of fertilization that leads to seed set. Watch a time-lapse video to further illustrate how a flower changes over time. Complex questions that need further research can become part of the next phase of learning.

Elaborate:

During this phase, students go outside to apply newly-gained knowledge. They are encouraged to view a wide selection of flowers in their natural settings so they can see that not all flowers are “perfect.” Some only have stamen, others have multiple pistils, the number of petals differ, and not all pollen is yellow! This phase is sometimes a deeper level of exploration, one during which important questions may arise and true curiosity can spark an investigable question or further research.

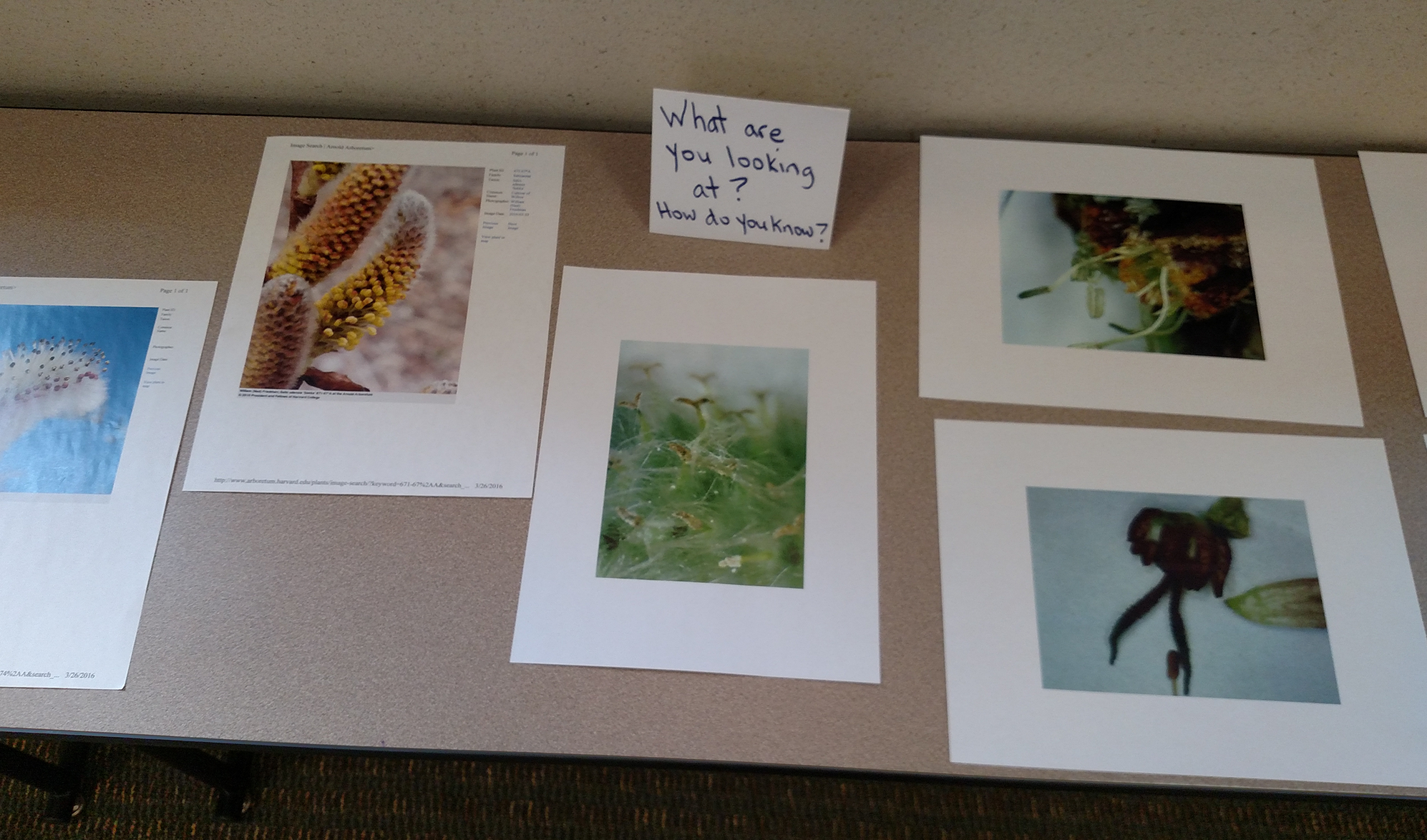

Evaluate:

Here are some ways for teachers to assess student learning: a) give each child a new flower to dissect and instruct them to learn all they can about the flower, drawing and labeling all known parts with explanations; b) give students photos of partial flowers to describe what they are looking at and explain how they know; c) create a comic strip narrative that explains how flowers are fertilized, making sure to use correct vocabulary and accurate drawings. In each of these examples students are asked to make sense of their learning and synthesize the important parts with a view toward generalizations and concept formation.

Educators came away with many new ideas to incorporate into their teaching practice, as well as a better understanding of how to use the outdoors for meaningful science content learning.

Learning about conifers

Feb. 8, 2019 | By Ana Maria Caballero, Nature Education Specialist

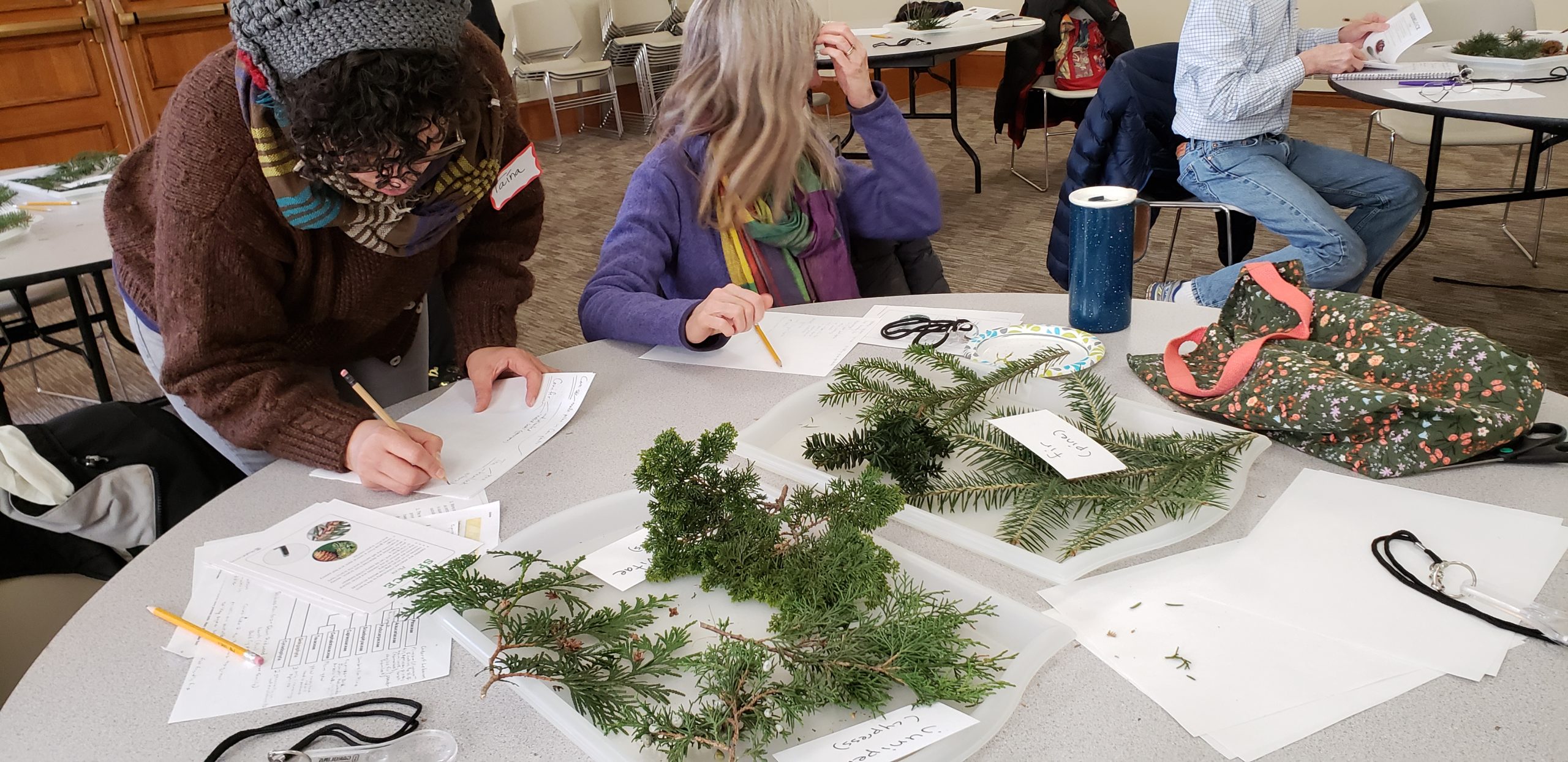

The brutal cold brought on by the polar vortex lingered long enough to make it almost impossible to enjoy the Conifer Collection up close on Saturday, Feb 2. Instead, teachers attending the monthly Arboretum for Educators to learn about conifer adaptations spent time indoors with collected plant material.

The program began with a general introduction to the gymnosperms and an overview of the various divisions within, focusing on the Pinophyta, commonly known as conifers. Teachers spent extended time touching, smelling, observing and sketching the various conifer families: Pinaceae (pine), Cupressaceae (cypress), Taxaceae (yew), and Sciadopityaceae (umbrella pine). Special attention was paid to leaf shape – scale, needle, or awl – and leaf arrangement, along with smell and texture for help in identifying general characteristics of each family. There are two more families, Araucariaceae and Podocarpaceae, but they are not represented in the Arnold Arboretum collections since they are from warmer southern hemisphere climates.

Next, teachers focused on several genera of the pine family that are commonly found in New England: hemlock (Tsuga spp.), pine (Pinus spp.), fir (Abies spp.), and spruce (Picea spp.). We are lucky in that the cedar of Lebanon (Cedrus libani) is part of the Arboretum collection, so teachers also had access to that pine family genus as well.

One of the goals of the Arboretum for Educators program is to help teachers learn more about botany and local natural environments and then help them translate this information in ways that are student-friendly and engaging. So, teachers were delighted to learn that spruce needles generally have square cross-sections and are spikey to the touch, while fir needles are flat (do not roll between fingers) and friendly to the touch. Similarly, teachers were surprised to learn that conifers have separate male and female structures, and that these are found on different branches on the trees (male cones on the lower branches and female cones further up), or on different places along the branch.

A lively discussion ensued: what is the advantage for trees to keep their pollen structures low to the ground? A teacher noted this is the opposite of what happens with corn. Do conifers self-fertilize? Why are the arils of the yew poisonous – wouldn’t this prevent the species from surviving? These questions stimulate more questions and further observation and learning, precisely what we hope students to engage in as well!

Towards the end of our time together, teachers wanted to apply their newfound knowledge outdoors. We ventured around the Hunnewell Building, discovering and identifying many of the same species that had captivated teachers indoors. By modeling and engaging in outdoor learning as adults, teachers can become more confident in bringing student outdoors and open a whole new world for scientific learning.

The Arboretum for Educators events aim to introduce seasonal natural phenomena to teachers and model ways in which students can engage in outdoor learning; teachers then are shown how to bring that learning back into the classroom for further investigations. Please join us at our next month’s event, Is It Spring Yet?

Impressions from a visiting professor

May 17, 2018 | By Ana Maria Caballero, Nature Education Specialist

Recently, the Arnold Arboretum hosted a six week visit by Olga Mayoral, a professor from the Department of Experimental and Social Sciences (Faculty of Teacher Training) of the Universitat de València in Spain. She is also a researcher at the Botanic Garden of the Universitat de València. Olga’s stay in March and April 2018 was provided by the Short-Term Funded Visits of Real Colegio Complutense at Harvard University.

The purpose of Olga’s visit was to establish contact with the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University through participation in public program activities and research talks. She also conducted a study within her ongoing topic of interest for research and publication: botanical gardens, arboreta, and outdoor environments as teaching and learning resources for various academic levels. Olga shared some of her impressions with us of her time at the Arboretum:

“During my stay I had the opportunity to get to know in detail the educational programs at the Arnold Arboretum and attend its various courses, lectures, workshops. I also had access to books and printed material not available at my University, connected with and observed elementary science teachers, and became familiar with the Massachusetts curriculum and standards for life science. Participating in Arboretum for Educators workshops gave me the opportunity to meet science teachers in the Boston area and visit some private and public schools where science educators use the outdoors for their science classes. Another interesting visit was to Boston Nature Center & Wildlife Sanctuary, where outdoor education is the norm across age groups. A special visit to the pre-school classes, where children spend around 80% of their day in nature, was especially satisfactory.

I’d like to focus on two programs in which I was immersed more deeply, programs that surprised me with the good practices and standards established by the people in charge of them. I could perceive the long-term goals that the organizers had developed, which had a direct effect on the commitment of the volunteers and teachers involved. The way these programs are organized ensure high quality standards and encourage the engagement of all. Participants feel as if they were a part of the Arboretum, which translates to important feelings of responsibility and pride.

Arboretum for Educators. This professional development program, ongoing throughout the academic year, gives teachers who are interested in including fieldwork in their natural science classes the essential tools and necessary confidence needed when teaching outdoors with children. In particular, educators end up understanding that the Arboretum is a perfect area to develop various science activities and to improve children’s knowledge of science content, while developing a scientific way of thinking and acting. That is, focusing also on the process and practices of science and not only on content knowledge.

Field Study Guide Volunteer Training. This program trains more than 40 volunteers to help guide learning during Field Study Experiences for Boston Public School students. Beginning with the process for volunteer recruitment, one can perceive that “cultivating young scientists through hands-on exploration” will be carried out in a satisfactory way. These Field Study Guides help over 2,400 students each year get involved in real field work activities. But always in small groups, a necessary premise almost never achieved at other centers.

The huge well-structured manual that each volunteer receives, together with on-going training and topic-based classes, help ensure that volunteers receive both conceptual and procedural knowledge content, and pedagogical practices based on the cognitive characteristics of each age group. This comprehensive training confers to the volunteers the knowledge and confidence necessary to lead groups of students at different ages.”

While at the Arboretum, Olga also offered a lecture titled “Environmental management complexity in eastern Spain—on the path to sustainability?” on April 18. Additionally, Olga and Ana Maria Caballero, Children’s Education Fellow, presented a webinar through the Real Colegio Complutense at Harvard University. The topic was “Science Outdoor Education: challenges in science teacher training”—you can view the webinar here.

Spring marches on, despite snow

March 14, 2018 | By Ana Maria Caballero, Nature Education Specialist

Boston educators entered the landscape this past Saturday (March 10) searching for signs of spring, and boy, were there many! Among chirping birds, the red-winged blackbird made an appearance, as did a few woodpeckers. Pairs of red-breasted robins hunted for nesting materials while evading a juvenile red-tailed hawk overhead. Teachers were fascinated by the large, silvery white catkins of Salix gracilistyla, the rosegold pussy willow, and even more intrigued by Salix gracilistyla var. melanostachys, the black pussy willow, growing along Meadow Road. A stomp through the wetland revealed dozens of skunk cabbages, their brownish-purple spathes poking through the mud, alongside wild onion and the emerging tips of irises and cattails. Snowdrops and daffodil greens peppered the ground underneath leafless trees with swollen buds. Hamamelis x intermedia ‘Arnold Promise’, a cultivar of witch-hazel, beckoned all to look closely at its delicate, curly petals. Beside Faxon Pond, teachers were also fascinated with the male catkins of Corylus avellana, the European filbert. Next to these, a few female flowers were beginning to show their fuchsia petals. Yes, spring was everywhere to be found.

Returning to the Hunnewell Building lecture hall, teachers engaged in a lively discussion centered on helping students identify testable questions for self-directed investigations. The new Massachusetts Science standards, along with Next Generation Science Standards, require that students engage in the practices of science. “Effective inquiry-based learning motivates students to ask questions and design scientific investigations related to their own interests and observations,” (Morgan and Hiebert, 2010). By starting with an outdoor exploration that raises questions for children to explore, teachers can help students frame testable questions that will lead to meaningful experiments. Younger students learn to identify testable questions from a pair of choices, and can use sentence stems to help frame their own questions. Older students benefit from re-writing untestable questions in an effort to more deeply understand their structure. Repeated experiences with outdoor exploration, asking questions, and discussing possible avenues for experimentation leads to better science learning, and engagement with the practices of scientists.

Tree Architecture Primer

Jan. 10, 2018 | By Ana Maria Caballero, Nature Education Specialist

Despite the bitter cold on Saturday, January 6, the Arboretum for Educators program “Examining Tree Architecture” went ahead (almost) as planned. Andrew Gapinski, Manager of Horticulture, used photographs to show attending educators the many factors behind a tree’s shape, and why it looks the way it does. Teachers also experimented with documenting tree shape through sketching techniques, culminating in a discussion about different ways they might use science or nature journals with their students to enhance life science learning.

See some of the participants’ journal entries with their corresponding trees in the photo gallery.

“The best part about today is that you didn’t cancel!” – Mary Smoyer, K and Gr. 2 volunteer educator, Trotter School, Boston, MA.

“I love it – I’m pretty sure I can work in some engineering problems for my students to solve based on tree architecture.” – Thea Cox, K-5 after school science program specialist, Lexington Public Schools., MA.

Teachers search for tree bark

Dec. 5, 2017 | By Ana Maria Caballero, Nature Education Specialist

On Saturday, December 2, a group of Boston area teachers searched for trees whose bark resembled string cheese, camo pants, saggy socks, or peeling paint! They found seven son flower (Heptacodium miconioides 1549-80*B), Japanese stewartia (Stewartia pseudocamellia 8-43*A), purple European beech (Fagus sylvatica ‘Atropunicea‘ 452-51*A), and paperbark maple (Acer griseum 279-62*A), among many other examples of trees with interesting bark. Teachers also enjoyed touching the bright papery bark of the white barked Himalayan birch (Betula jacquemontii 74-94*A) and the thick, rough peeling bark of the shagbark hickory (Carya ovata #12907*G). Children, and adults it turns out, really begin to see trees anew when they compare tree bark to familiar, everyday materials and food. The fun is in the search, and then using specific vocabulary to describe what is touched and observed.

The walk began at the Centre Street gate and continued down Bussey Hill Road, through the Leventritt Shrub and Vine Garden, onto Linden Path, and down Meadow Road towards the Hunnewell Building. Along the way, teachers learned about the many uses of bark as well as some of its functions. For example, indigenous Americans boiled shagbark hickory bark to extract sugar and medicinal properties, while birch bark can be used as kindling to start fires because it contains flammable oils that will burn even if the bark is wet. In addition, the exfoliating or peeling nature of some bark removes lichen than can block lenticels, allowing for higher rates of transpiration and gas exchange. Thick bark protects the tree from temperature extremes and water loss, and cracked bark is less attractive to herbivores. Who knew? As one teacher put it, “I had no idea there are so many bark types! I’ve never looked closely before and am excited to share with my students.”

Once inside, teachers could choose to make close observations of tree twigs. Reference sheets helped them to learn about and identify the scars, notches, and bumps on twigs (leaf scars, terminal bud scale scars, and lateral buds). Each twig is different, but all twigs will reveal their secrets upon careful study.

The second option was to create a model using coffee stirrers, straws, paper, wooden dowels, and cardboard tubes to represent the outer and inner bark (phloem), cambium layer, the xylem transport system, and pith inside trunks. As Thea, a participant, put it: “The tree models we made are a great way to demonstrate concepts that kids need more than observation to learn. I think kids in my program would love building these.”

The Arboretum for Educators is a free, monthly offering to Boston area educators who want to learn more about using the outdoors for science education. Join us next month, January 6, 2018, to learn about tree architecture!

Investigating winged seeds

Nov. 8, 2017 | By Ana Maria Caballero, Nature Education Specialist

In Massachusetts, engineering and technology curricula standards for Kindergarten through second grade require that students be taught how to test and compare the strengths and weaknesses of different objects intended to solve the same design problem. At the Arnold Arboretum, teachers from Boston area schools gathered on Saturday, November 4 to do just that, using a large sample of winged seeds (samaras) found in the landscape.

Tossing different samaras from a consistent height allowed teachers to observe the flight path of each seed, determine its hang time, and record observations on a large chart. Teachers also spent time noticing the placement of the seed within the fruit structure, the shape of the wings, the size, dryness, and other attributes of each samara that contributed to the many variables to consider during testing. Taken together, this data could be used to engineer the “perfect” winged seed—one that will stay aloft the longest in order to catch the wind and disperse furthest away from the parent tree.

Teachers enjoyed walking along Meadow Road and collecting and examining a wide variety of fruit, including berries, magnolia pods, cattail fluff, burdock, maple samaras, and rose lantern pods. They performed brief tests in-the-field to confirm their predictions regarding the various dispersal strategies plants use to ensure their species’ survival. Teachers walked away with bags full of seed packages to take to their classrooms for further studies.

This “Mechanics of Flight” investigation was part of the fall theme of our Arboretum for Educators program examining seed dispersal strategies. Held monthly and free of charge, Arboretum for Educators programs aim to help classroom teachers and science specialists teaching Pre-K through Grade 8 to become more familiar with trees and learn how to use plants and the outdoors as an integral part of teaching.

Exploring freshwater habitats

May 10, 2017 | By Ana Maria Caballero, Nature Education Specialist

In between raindrops on a muggy Saturday morning, several educators gathered at the ponds to explore life in and around freshwater ecosystems. Armed with plankton nets, plastic containers, small spoons and a set of macroinvertebrate cards, teachers made amazing discoveries. Among the organisms collected were a damselfly nymph, hundreds of daphnias (water flea), some aquatic worms, several fast moving freshwater shrimp known as scuds, a water boatman, some other type of water beetle and many water striders.

We also saw (or heard) many birds, frogs, turtles, geese and even a pair of wood ducks!

After about 1 hour of exploration, the water samples and organisms were brought back to the Hunnewell Building lecture hall for further examination and identification. Using pipettes and Petri dishes, collected samples were observed under microscopes, where whole new worlds were revealed! By comparing body structures, shape and size to ID sheets and field guides, teachers were able to determine what they were looking at, and share in the excitement of discovery and learning. Under magnification, we saw copepods with egg sacs, and noticed that many of the water fleas had eggs in a brood pouch.

Teachers gained an appreciation for biodiversity of animal life in freshwater ponds, and learned simple techniques for collecting samples and examining them under all types of magnification devices. Learning to “do” science in the field, and using tools back in the classroom for identification and gaining knowledge is an exciting way for teachers and their students to work as scientists.

The Arboretum for Educators aims to introduce Boston teachers to outdoor education with a variety of experiences in the landscape that highlight life science concepts. Activities are meant to be easily replicated in outdoor classrooms at schools, or other outdoor spaces near where the students learn, as well as provide teachers with knowledge and opportunities to lead self-guided field trips in the Arboretum landscape.

Searching for signs of spring

March 10, 2017 | By Ana Maria Caballero, Nature Education Specialist

A 20°F morning did not deter several Boston area educators from coming to the Arboretum this past Saturday for a close look at the many signs of spring visible in the collections. The landscape is already preparing for the new season, even if we are still clinging to our mittens, hats, scarves, and winter coats. This is evidenced by the arrival of several chirping birds, among them the easily recognizable red-winged blackbird. A pair of possibly-nesting ducks and geese were also enjoying a leisurely swim at the ponds.

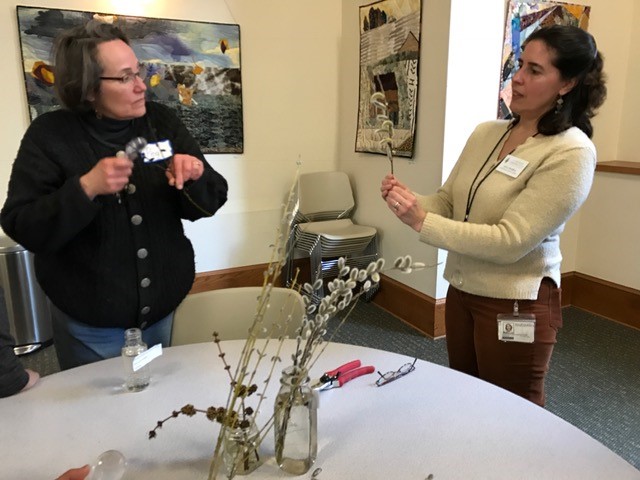

Unable to venture outside for a spring search, educators nonetheless explored samples of flowering trees indoors. Teachers were fascinated by the large, silvery white catkins of the Rosegold pussy willow (Salix gracilistyla 690-75*A), and even more intrigued by the black pussy willow (Salix gracilistyla var. melanostachys 404-82*A.) They learned that these catkins are the male reproductive parts; some were already showing stamens with abundant pollen. A silver maple (Acer saccharinum 12560*C) twig bearing clusters of male flowers proved equally fascinating. Finally, a cultivar of witch-hazel (Hamamelis x intermedia ‘Arnold Promise’ 396-69*A) beckoned a closer look at its delicate and curly petals.

The brownish-purple spathes of skunk cabbage that dot the landscape at the edge of the meadow provide another sure sign of spring, alongside patches of wild onion and snowdrops. When working with children, it is important to engage all the senses in learning, and these plants really step up their game in terms of scent! Engaging the ears and eyes is easily accomplished through time-lapse videos of spring flowers blossoming and close-up footage of migratory birds singing. Thus, even when going outside is not an option, children and adults can still revel in the beauty of the new season.

Following this period of nature exploration, teachers engaged in a lively discussion centered on helping students identify testable questions for self-directed investigations. The Massachusetts Science, Technology and Engineering standards, along with Next Generation Science Standards, require that students engage in the practices of science. “Effective inquiry-based learning motivates students to ask questions and design scientific investigations related to their own interests and observations,” (Morgan and Hiebert, 2010). By starting with an outdoor exploration that raises questions for children to explore, teachers can help students frame questions that are testable—that is, questions which lead to meaningful experiments. Younger students learn to identify testable questions from a pair of choices, and can use sentence stems to help frame their own questions in this manner. Older students benefit from re-writing un-testable questions in an effort to understand their structure. Repeated experiences with outdoor exploration, asking questions, and discussing possible avenues for experimentation leads to better science learning and engagement with the practices of scientists.

Boston teachers learn how to read twigs

Jan. 12, 2017 | By Ana Maria Caballero, Nature Education Specialist

An editor reads books. A mathematician reads numbers. A doctor reads x-rays. A botanist reads…..TWIGS!

On Saturday, several Boston area teachers became botanists for the morning. Michael Dosmann, Curator of Living Collections, taught teachers how to interpret the bumps, shapes, and nicks on a twig.

The variety of terminal buds alone makes for interesting reading. Each bud is protected by bud scales, which are modified leaves that completely cover the delicate tissue, and prevent winter’s ill effects. There are the rubbery, smooth duckbill of the tulip tree; the large, sticky bulb of the horse chestnut; the fuzzy cap of the magnolia; the sharp, slender spear of the beech; the clustered crown points of the maple; and the deer hooves of the katsura tree. Moving further back from the terminal bud, one may find lateral buds, sometimes in opposite arrangement on the twig, and sometimes alternating along its length. Teachers learned that a bud contains all the parts for next season’s leaves, flowers, and stems. Wow!

Each lateral bud is preceded by a leaf scar—the place where the previous season’s leaf used to attach. Leaf scars are also distinctive, sometimes triangular, circular, or crescent shaped. Within those leaf scars one can glimpse tiny dots known as bundle scars. These are the ends of veins that transported food and water between leaf and twig. A strong twig reader can identify many tree species by decoding the combined clues of bud, arrangement, and leaf scars.

If you continue reading backwards from the terminal bud on the twig, you might find some rings that might resemble saggy socks in appearance. These growth rings, known as terminal bud scars, remain after the bud scales of the previous year’s terminal bud fall off. This section represents one year’s growth. By counting sections between growth rings, one can discover the age of that twig or branch.

Armed with this information, teachers went out into the landscape to practice newly gained twig reading skills. And as any teacher knows, the more we practice reading, the better (twig) readers we become!