Excerpted from chapter 2 of Boston's Franklin Park: Olmsted, Recreation, and the Modern City, by Ethan Carr. Published by the Library of American Landscape. Copyright © 2023, all rights reserved.By the summer of 1884, the visiting public was already engaged in patterns of uses and activities that would define the future park. In Septembe the commissioners authorized Olmsted to produce a preliminary plan, and at the end of the year he reported his initial intentions. He wrote that the “prime object” of the park was to enhance, preserve, and make accessible “a body of rural and sylvan scenery, large in scale, simple and tranquil in character; and in contrast and as a foil to this, passages of a wild, rugged, picturesque and forest-like aspect.” With the right design, this could be done while also creating a “place of general congregations,” where carriages, horseback riders, and everyone else could all meet “without clashing” in the “enjoyment of a gay throng.” The same was true for grounds “suitable for public festivities” of a wide variety, and extensive picnic areas, especially for those “unable to go out of town during the summer.” He also suggested that a suitable area of the park could be leased for the operation of a zoo. As long as these features were located and designed “without crippling the park for its main object,” a full range of activities and programs—as existed in Central Park and Prospect Park—could be achieved in an overall composition without sacrificing the rural character that was the landscape’s primary value.1 In 1885 the park commissioners gave West Roxbury Park a new name: Franklin Park. Benjamin Franklin was honored because a bequest he made to the city was scheduled to mature in 1891, and they hoped the funds would be used to pay for construction.2

Olmsted often emphasized the degree to which the site of Franklin Park would be easily transformed into an ideal “large park” at low cost. The public’s enthusiastic and rapid adoption of the landscape confirmed its ready adaptability. By the 1880s, many park commissions knew that selecting an already scenic area for a large park reduced construction expenses. If they were not aware of it, Olmsted was always quick to make the point, since it was a good argument for selecting sites with maximum potential. For Olmsted, the design of large parks was a practice that had always involved preserving existing landscape character as much as developing new “effects,” or experiences. Making a park entailed doing more, or doing less, to achieve the same goals.

When he and Vaux had struggled with the notoriously unpropitious site for Central Park, extensive soil amendments and elaborate subsurface drainage systems were required in many areas, and innovative sunken transverse drives prevented the division of the landscape by the city’s street grid. The result was costly, reported by Olmsted to be $14,000 per acre—the same cost as the heavily engineered Back Bay Fens. Prospect Park, where Olmsted and Vaux had more control of the boundaries of the area and less engineering was required, came in at $9,000 per acre. The Brooklyn park nevertheless was considered by many the greater work of art because it achieved more expansive landscape effects—the Long Meadow and the Lake—than had been possible on the Manhattan site, which had been chosen for reasons other than its potential as an enhanced rural landscape.3

In 1885, Olmsted projected that the total cost of Franklin Park would be $2,900 per acre. Certainly the estimate was an economic argument for the desirability of the design he presented at that time, and no doubt it appealed to the always parsimonious Boston officials. But the estimate also quantified how much improvement would be required to realize the intended results on the site, and it indicated the degree to which the existing landscape suited its new purpose.4

The amount of development needed to make a place a park was a function of the site’s character and condition, not just a question of saving money. In 1858, Olmsted and Vaux proposed that the north end of Central Park, which was a relatively undisturbed, wooded area, be “interfere[d] with” as little as possible: it already possessed a desirable “picturesque” character and required only the construction of the park drive, paths, and overlooks.5 Most of the park budget was spent on the south end, where conditions demanded extensive improvements. In 1868, when Olmsted toured the proposed site of Delaware Park, the large park of the Buffalo system, he advised, “Here is your park, almost ready-made,” a reaction similar to what he expressed to Dalton in 1876.

Throughout his career, Olmsted based his designs of large parks on a response to the contingencies of the sites chosen for systems of public landscapes. While those choices were made by park commissions, Olmsted often had an advisory role, as he did in Boston. Park design involved devising the best response to the site—defined in both aesthetic and economic terms—whether it was a waterfall in western New York, a mountain in Montreal, or the pastures and wooded ledges of West Roxbury.6 For Olmsted, no conflict existed between preserving the site of a large park and designing the roads, paths, and other features that allowed it to function and enhanced its enjoyment. When properly planned, such development was the means of preservation, since it choreographed public activities, mitigated their impact, and assured a constituency opposed to developing the area for other public or private purposes.

The Language of Linked Landscapes

As Ethan Carr makes clear in the book excerpted here, Franklin Park is one of the crown jewels of the Emerald Necklace. Whence the necklace metaphor? Frederick Law Olmsted did not coin the term “Emerald Necklace”; for Olmsted and city officials, it was simply the Boston Park System. Some still-unknown person created the term sometime in the middle of the twentieth century. The resonance of that term, indicating landscapes linked by parkways, underscores Olmsted’s singular vision for the Boston Parks. The system became the necklace, and the necklace became a national metaphor for linked parks in Atlanta, Cleveland, Rochester, Milwaukee, Los Angeles, and other urban settings.

Olmsted’s skill in negotiating with the city while holding on to his principles gave Boston the great park system it has today, in the form of distinct spaces linked by parkways. Olmsted resisted calling most of the segments “parks,” a term suggesting traditional amenities that these spaces could not and should not provide. With the exception of Franklin Park, segments were named for their natural character: fens, river, kettle pond. In 1887, when pushed by the Boston Commissioners to add a distinctive name to the system as a whole, Olmsted suggested the term “Parkway.”

The idea of linked public landscapes did not originate with Olmsted, however. In 1855, the planners Horace William Shaler Cleveland and Robert Morris Copeland designed Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Concord, Massachusetts as part of a system of public spaces. In 1927, the landscape architect Stephen Child referred to the Boston system as a “jeweled girdle . . . a regal adornment any city might proudly clasp around its throbbing, pulsing life.”

Carr shows us that park systems are dynamic; change is inherent. Olmsted’s plans and detailed narratives give contemporary landscape architects and community groups a road map to protect and enrich Boston’s Emerald Necklace.

—

Phyllis Andersen is a landscape historian and former director of the Institute of Cultural Landscape Studies of the Arnold Arboretum

“The problem of a park,” Olmsted wrote in 1881, was “the reconciliation of adequate beauty of nature in scenery with adequate means in artificial constructions of protecting the conditions of such beauty, and holding it available to the use, in a convenient and orderly way, of those needing it.”7 The results—large parks—were works of art, but none could be described as artificial constructions or objects, as in other artistic disciplines. Neither did Olmsted make a qualitative distinction between large urban parks and the even larger “reservations,” such as the Niagara State Reservation, that appeared outside cities beginning in the 1880s. The advice given, the design, might differ, but the purpose and goals remained constant: creating sustainable public landscapes, accessible to all, in which healthful experiences of landscape beauty and vital community socialization could occur.

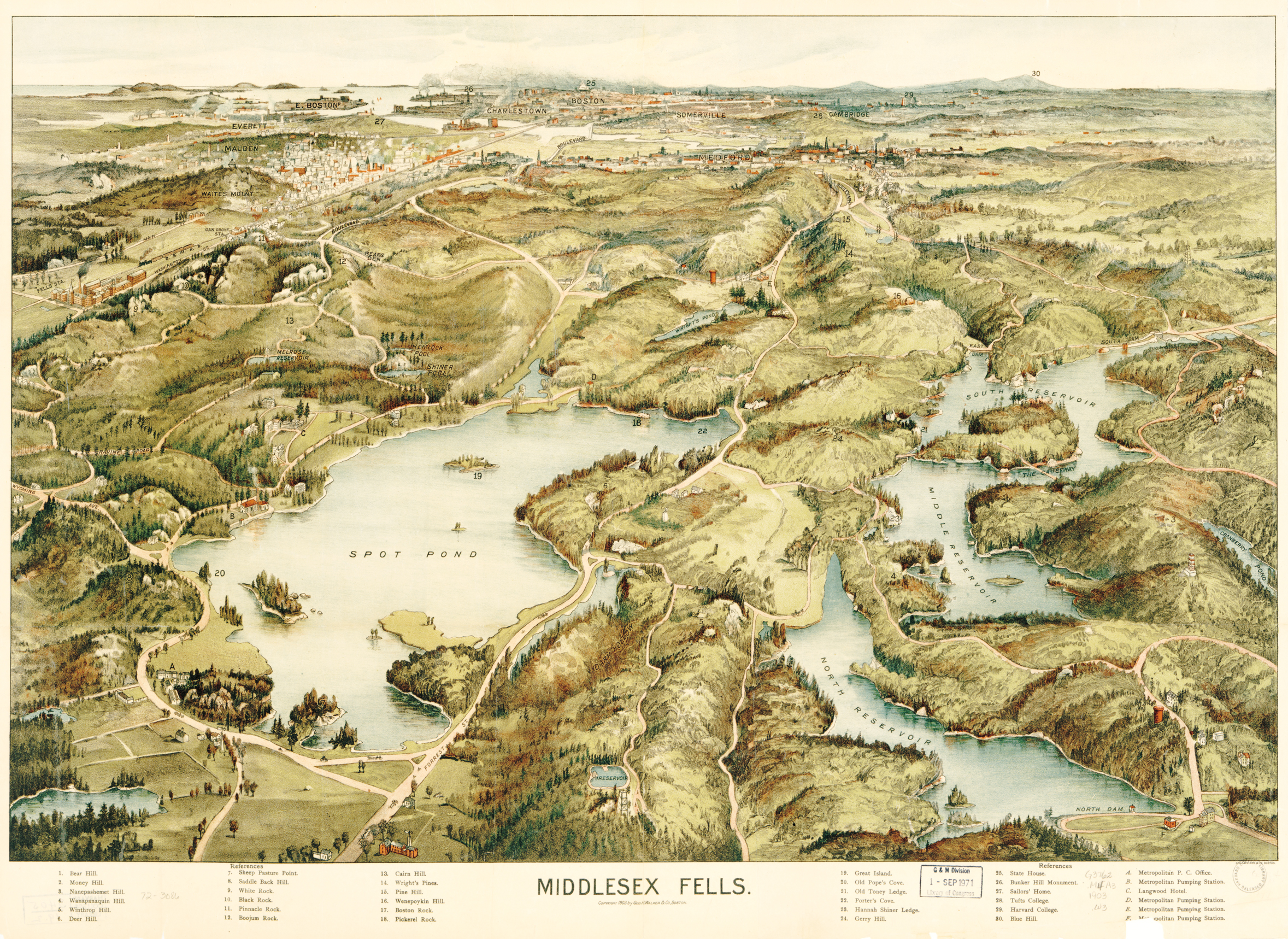

Nowhere was this more evident than in the plans for new landscape reservations in municipalities outside of Boston. In 1879, as he completed the designs for the Back Bay Fens and the Arnold Arboretum, Olmsted went twelve miles north to Lynn, where citizens and officials were advocating for a “free public forest” that would become the Lynn Woods Reservation. The next year, the journalist and park advocate Sylvester Baxter asked him to advise on the creation of another reservation nearby, the Middlesex Fells. Both covered areas of more than two thousand acres and featured woodlands, ponds, and dramatic, glaciated geology. Olmsted advised that trying to make such landscapes “park-like” was hopeless and would be an expensive failure. The wooded, rocky sites should be taken for what they were, and their “natural characteristics” should be the basis of whatever limited improvements were required to make them valuable retreats for nearby residents and for the people of the entire region. Forestry management that would “enlarge, strengthen, and emphasize a local character” should be the first priority. Minimal “roads and walks, bridges, shelters and other constructions” could be quickly built (later) and should not attempt the degree of “finish” appropriate for many urban parks.8

The expansion of park planning to the regional scale, however, would primarily be the work of Charles Eliot (1859–1897), who joined the firm as an apprentice in 1883. Eliot worked closely with Olmsted for two years and participated in early investigations and preliminary designs for Franklin Park. He went on to start his own office in 1886, eventually returning to Fairsted as a partner in 1893. Well-connected socially and politically, Eliot in 1889 suggested the creation of the first land trust: a nonprofit and tax-free organization that could receive gifts of land to hold in trust for the benefit of the public. The state passed legislation to form The Trustees of Public Reservations in 1891, and Eliot was named chair of the standing governing committee.

Working with Sylvester Baxter, Eliot also lobbied for a “metropolitan” park commission. Established in 1892, it was the first regional park commission of its type, and Eliot was named consulting landscape architect. Until his death in 1897 at the age of thirty-eight, he oversaw the acquisition and development of more than nine thousand acres of parks—a collection of regional landscape types, including beaches, estuaries, forests, and characteristic geological formations—in thirty-seven separate municipalities around Boston. The Blue Hills (the background of several views in Franklin Park) became one of the first reservations created in 1893, along with the Middlesex Fells, Waverly Oaks (Beaver Brook), and Stony Brook reservations. In 1890, Eliot expressed goals for these regional parks that echoed Olmsted’s for Franklin Park: “A crowded population thirsts, occasionally at least, for the sight of something very different from the public garden, square, or ballfield. The railroads and new electric street railways which radiate from the Hub carry many thousands every pleasant Sunday through the suburbs to the real country . . . for the sake of the refreshment . . . the country brings to them.”9

For Olmsted, the design of large parks was a practice that had always involved preserving existing landscape character as much as developing new “effects,” or experiences.

Olmsted had increasingly emphasized doing less and relying more on the character of the site to produce a composition of landscape effects, culminating in his design for his last great park. Eliot took the next step, emphasizing to an even greater degree the preservation of existing features and distinctive qualities of a landscape. Writing about the metropolitan reservations shortly before he died, he predicted that “it is . . . quite unlikely that there will ever be any need of artificially modifying them to any considerable degree. Such paths or roads as will be needed to make the scenery accessible will be mere slender threads of graded surface winding over and among the huge natural forms of the ground.”10 For Olmsted, both park systems were a single, integrated project: urban landscape planning extended into regional landscape planning. Both could be structured by siting and designing a range of public landscapes serving multiple functions and purposes. In 1893 he wrote to his stepson, J. C. Olmsted, and Eliot (both now his partners):

Our reputation is still to be made . . . in such “wild” public grounds, as those that we are now first to engage with about Boston. As much is to be made in this respect, as was to be made in Central Park. In your probable life-time, Muddy River, Blue Hills, the Fells, Waverly Oaks, Charles River and Beaches, will be points to date from in the history of American Landscape Architecture, as much as Central Park. They will be the opening of new Chapters of the Art. And there will be fashions starting from them, which will run across the Continent.11

This would in fact be the case. Over the next fifty years regional, county, and state park commissions proliferated. The national parks coalesced and expanded into a system after Congress created the National Park Service in 1916. Almost all of these new park agencies hired landscape architects to plan and design their parks. Through the 1920s and 1930s, their work continued and elaborated on a practice of large-park making that had germinated at Fairsted and taken root through the experience of creating Franklin Park and the metropolitan reservations around Boston.12

Franklin Park looked two ways: back to the municipal large parks of previous decades and forward to the regional reservations, state parks, and national parks that were to come. This perspective is especially evident in the design of the landscape structures and buildings in the park, which showed the results of a rich period of innovation by Olmsted and his collaborators in the early 1880s. Preeminent among these was H. H. Richardson. In the 1870s the two had worked together on the Buffalo State Hospital for the Insane, the New York State Capitol, and other projects. Following the 1877 completion of his Trinity Church in Boston, Richardson was one of the most influential architects in the country.

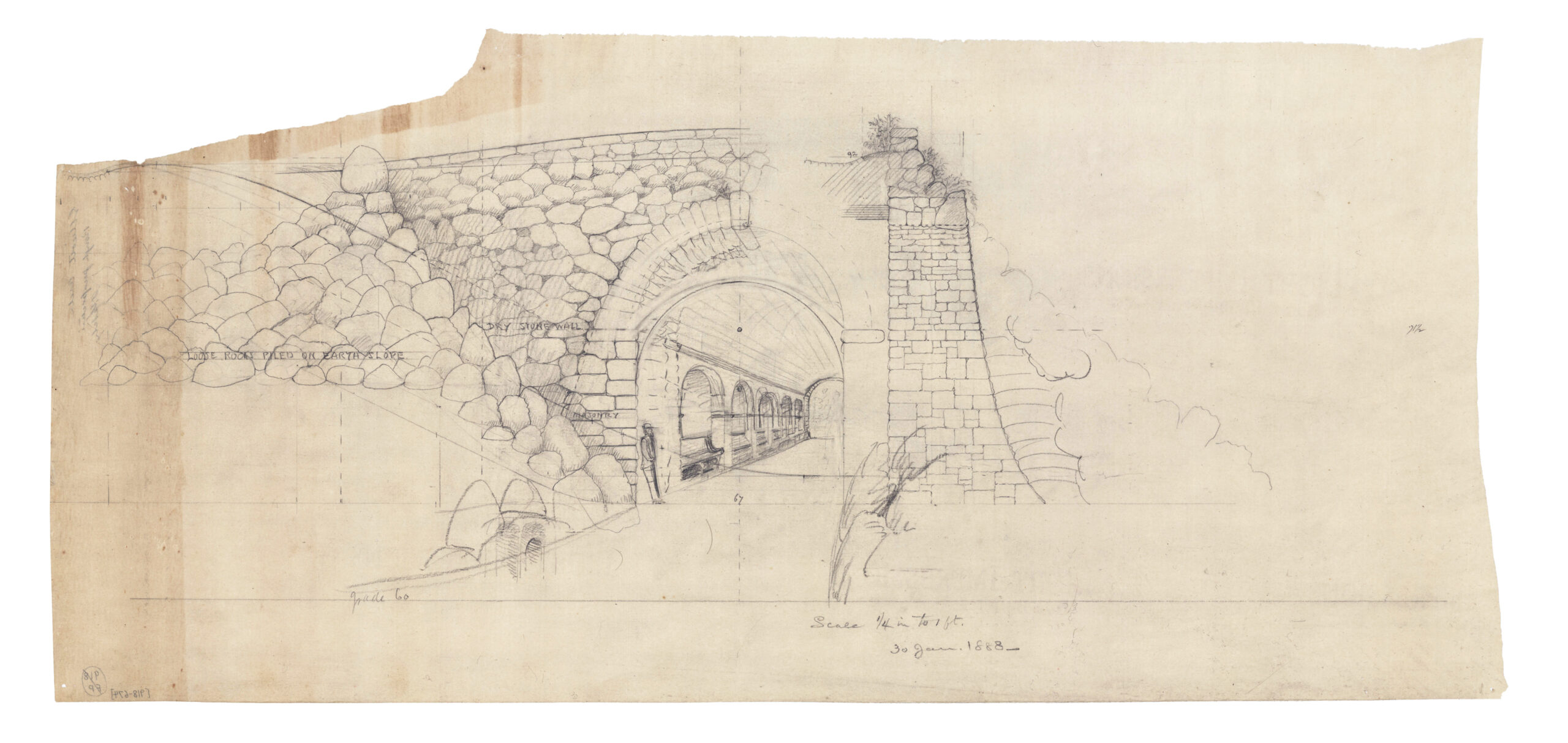

In 1880, Olmsted asked him to design the Boylston Street Bridge as part of the Back Bay Fens landscape. The bridge formed a major portal into the Fens, while carrying intersecting traffic over the park. Richardson designed an undulating mass of irregular ashlar masonry inspired by the surrounding landscape forms and geology and devoid of historical details or ornamentation. The architect understood that Olmsted rejected the gardenesque displays of, for example, the Public Garden, and produced an architectural idiom consistent with the overall evocation of a tidal estuary. Both designers moved beyond stylistic eclecticism to produce an integration of landscape and architecture rooted in an organic, geologic aesthetic. The architectural historian James F. O’Gorman describes the bridge as a “complete collaboration between architect and landscape architect, between man and nature, between architecture and geology.”13

This was a new type of park architecture that differed significantly from most of that found in Olmsted’s earlier parks. For Central Park and Prospect Park, Calvert Vaux had provided playful and diverse bridges and other structures, usually in the popular Gothic Revival or another historical style. The architect Thomas Wisedell later worked with Olmsted in a similar vein for the structures of the U.S. Capitol grounds and other projects. But the collaboration with Richardson was profoundly and mutually influential in ways these earlier partnerships had not been. The Adirondack-inspired “rustic” structures of the Ramble and the north end of Central Park did feature rough stone construction and unfinished materials, and they were one inspiration for the direction Olmsted and Richardson took in the 1880s.14 But these examples were mostly limited to the wilder areas of the New York (and other) parks, and were part of an overall eclecticism in park architecture.

The boulder masonry buildings and structures that Olmsted designed in the early 1880s constituted an original and distinctive style, one that he employed throughout the Boston parks and in a number of other public and private commissions immediately before he began the design of Franklin Park. Many of these projects were in collaboration with Richardson, notably for the Ames family in North Easton, Massachusetts. The art critic and Richardson biographer Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer noted the significance of their mutual artistic influence during this period, for example, in the design of the Memorial Hall in North Easton. Richardson used the rocky site of the building to advantage, she observed, and Olmsted’s surrounding landscape enhanced the effect. The granite formations of the site were employed as design elements, and “the tower of the hall [rose] out of the rock, almost like a natural development.”15 Richardson, however, died at the age of forty-seven in 1886, leaving Olmsted to work with other amenable architects, such as Richardson’s successors at Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge and the firm Peabody & Stearns. But the Fairsted office also developed its own architectural design capacity, and the most important building in Franklin Park, the Overlook Shelter, would be designed by Olmsted himself.

As Olmsted prepared the plan of Franklin Park beginning in 1884, another important collaborator helped shape the distinctive architecture being developed. From the beginning, Olmsted wanted rough-boulder masonry construction for structures in the Boston parks (although for the Boylston Street Bridge he and Richardson acquiesced to granite ashlar). John H. Watson worked with him to develop the materials and techniques to realize this goal. Watson was a mason from Salem who specialized in rough-boulder retaining walls and other structures. He built the stone grotto on the U.S. Capitol Grounds in 1879 and the boulder retaining wall and terrace for the John C. Phillips estate (Moraine Farm) in Beverley, Massachusetts, the following year. It was Watson who constructed the remarkable Civil War memorial cairn and terrace in front of the North Easton Memorial Hall in 1882, and he worked on a number of Olmsted’s projects of the period.16 Watson would also build many of the landscape structures and site furniture in Franklin Park.17

Olmsted’s approach to the design of Franklin Park’s structures, shaped by his preceding collaborative innovations, was a distinctly new park architecture, one that would employ organic flowing forms, boulder masonry, and complete integration with the materials and structure of the landscape. The buildings, site details, and furniture of Franklin Park became influential precedents for how necessary construction in a large park could be unified with the intent and appearance of the landscape design—and left behind the eclectic (if delightful) Victorian confections of Vaux and Wisedell. This development in park architecture would not, however, primarily influence municipal parks. Fewer cities would continue to plan large urban parks in the coming decades. But regional authorities, counties, states, and the federal government were embarking on an intense period of park and park system development.

Many of these parks—or reservations—were indeed large. And many would employ boulder construction, local materials, and careful integration with sites in their development. By the 1920s, the National Park Service enshrined such work as “rustic” park architecture. The origins of this distinctive and pervasive style are to be found in Franklin Park. Olmsted’s last great municipal park prefigured the future of large parks, which would now more often be created in suburban, rural, and wilderness areas. But in the design of their structures—from buildings to roadsides, overlooks, and campgrounds—their lineage reaches back to Olmsted’s urban park design of the 1880s.

Ethan Carr Ph.D., FASLA, is a professor of landscape architecture at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Boston’s Franklin Park: Olmsted, Recreation, and the Modern City will be available this fall.

End Notes

1. Tenth Annual Report, 18–19.

2. Eleventh Annual Report of the Board of Park Commissioners [1885] (Boston, 1886), 20–24. The Franklin bequest was never used for the park. In 1908 the funds were used to establish a technical school, the Franklin Union. Richard Heath, “Franklin Park Notes,” Jamaica Plain Citizen, January 29, 1981, 8.

3. Many interests were involved in choosing the Central Park site. See Roy Rosenzweig and Elizabeth Blackmar, The Park and the People: A History of Central Park (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1992), 37–58.

4. The estimate included the costs of land, development, and maintenance as of 1885 and were included in Olmsted’s report accompanying his plan submitted to the park commissioners that year. FLO, “Notes on the Plan,” 507.

5. FLO and Calvert Vaux, “Greensward” [1858], PFLO 3: 119–87, quot. 119.

6. In 1869, while working in Buff alo, Olmsted led a campaign to preserve nearby Niagara Falls, and he and Vaux later completed the design for the Niagara State Reservation. Francis R. Kowsky, The Best Planned City in the World: Olmsted, Vaux, and the Buffalo Park System (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press / LALH, 2013), 33, 158–71. In 1874, when asked by the City of Montreal to make a park out of the mountain that rose up near the center of the island on which the city stood, Olmsted noted that a 700-foot-high formation of igneous rock was not suitable for a “park,” at least not the type of landscape he felt that word implied. He wrote in the report accompanying his 1881 plan: “It would be wasteful to try to make anything else but a mountain out of it; equally wasteful to attempt anything that would involve a loss of such advantages as it has for this purpose.” FLO to the Commissioners of Mount Royal Park, November 21, 1875, PFLO 7: 84–91; FLO, “Mount Royal” [1881], PFLO SS1: 350–418, quot. 379.

7. FLO, “A Consideration of the Justifying Value of a Public Park,” January 28, 1881, PFLO SS1: 331–49.

8. FLO to Sylvester Baxter, November 9, 1880, PFLO 7: 510–12, and August 20, 1889, PFLO 8: 721–23; FLO to Phillip A. Chase, November 29, 1889, PFLO 8: 752–55.

9. PFLO 9: 70–72; Charles W. Eliot, in Charles Eliot, Landscape Architect [1902], ed. Keith N. Morgan (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press with LALH, 1999), 317.

10. Charles Eliot, Vegetation and Scenery in the Metropolitan Reservations of Boston (Boston: Lamson, Wolff e, 1898), 7.

11. FLO to John Charles Olmsted and Charles Eliot, November 1, 1893, PFLO 9: 700–709.

12. See Ethan Carr, Wilderness by Design: Landscape Architecture and the National Park Service (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1998), 95–109.

13. James F. O’Gorman, Living Architecture: A Biography of H. H. Richardson (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997), 133.

14. See Frank R. Kowsky, “The Veil of Nature: H. H. Richardson and Frederick Law Olmsted,” in H. H. Richardson: The Architect, His Peers, and Their Era,ed. Maureen Meister (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999): 55–75.

15. Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer, Henry Hobson Richardson and His Works (1888; reprint, New York: Dover, 1969), 71.

16. See FLO to Oakes Angier Ames [April 1882], PFLO 8: 50–54.

17. PFLO 8: 203n6.