My first physical encounter with extinction was in a museum. I was at Oxford studying the legacy of colonialism, so my supervisor encouraged me to examine the dodo at the Natural History Museum. Familiar with Tenniel’s illustration in Alice in Wonderland of this famously extinct species of flightless bird, I imagined an imposing, feathered, taxidermized specimen. Instead, in a small vitrine, there was an isolated foot; a head, which Oxford also possesses, was not on display. I remember standing there, looking at the dodo’s toes, a haunting evocation of one of the world’s unique species reduced to bones.

This past summer, I was vividly reminded of the Oxford Dodo in Ebony G. Patterson’s exhibit, “… things come to thrive … in the shedding … in the molting,” at the New York Botanical Garden, where I serve as Vice President for Education. In Patterson’s (literally) ground-breaking installation, she explored the entangled themes of colonialism, slavery, and extinction through a variety of media. In front of the Enid A. Haupt Conservatory, the artist placed cast-foam sculptures of glittering black vultures to groom physical rifts in the landscape, while within, she surrounded a sculpture of an albino peacock—inspired by one Patterson had seen molting at the Hope Botanical Garden in Jamaica—with disembodied glass limbs that rose, gesturing, from lush plantings.

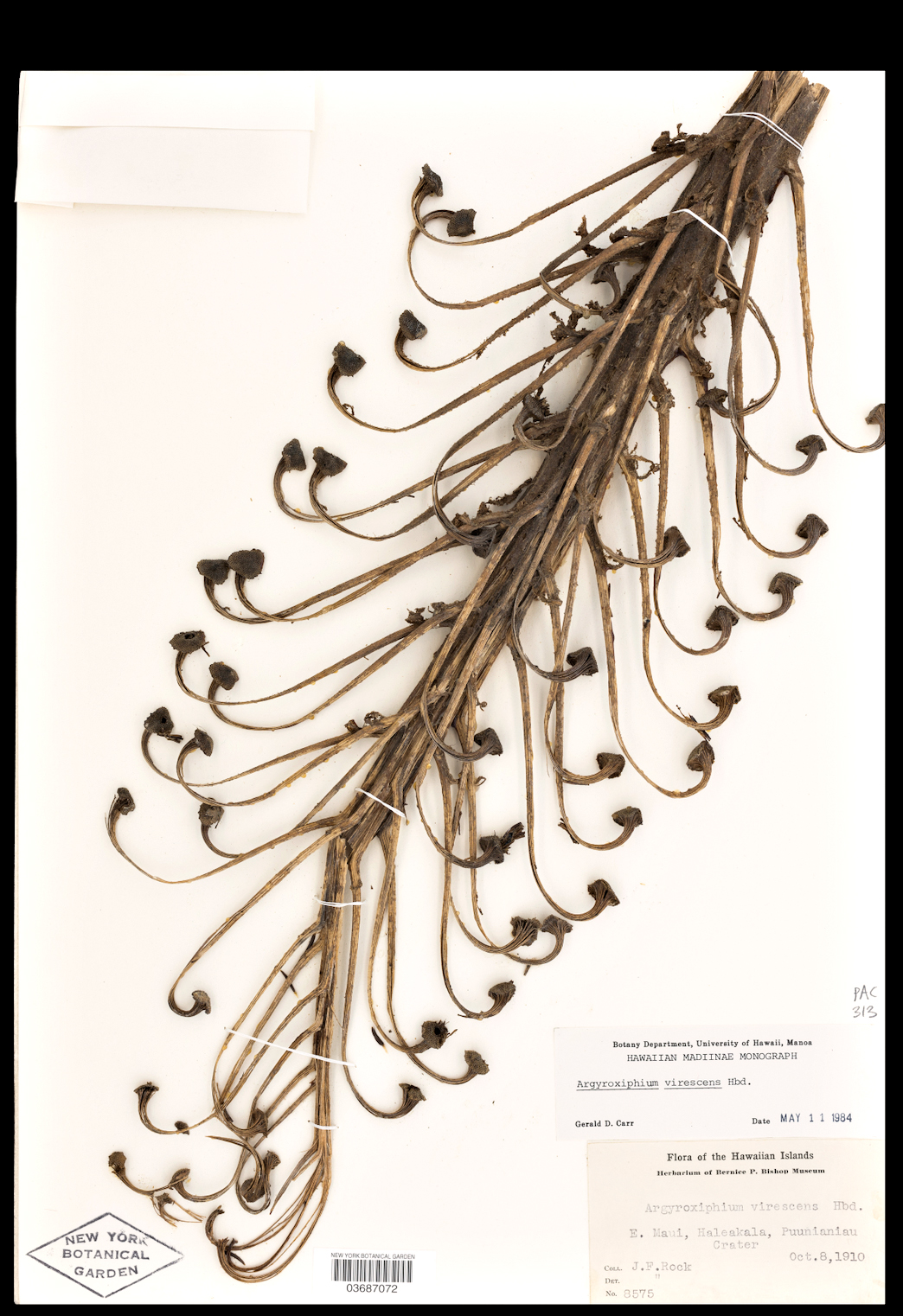

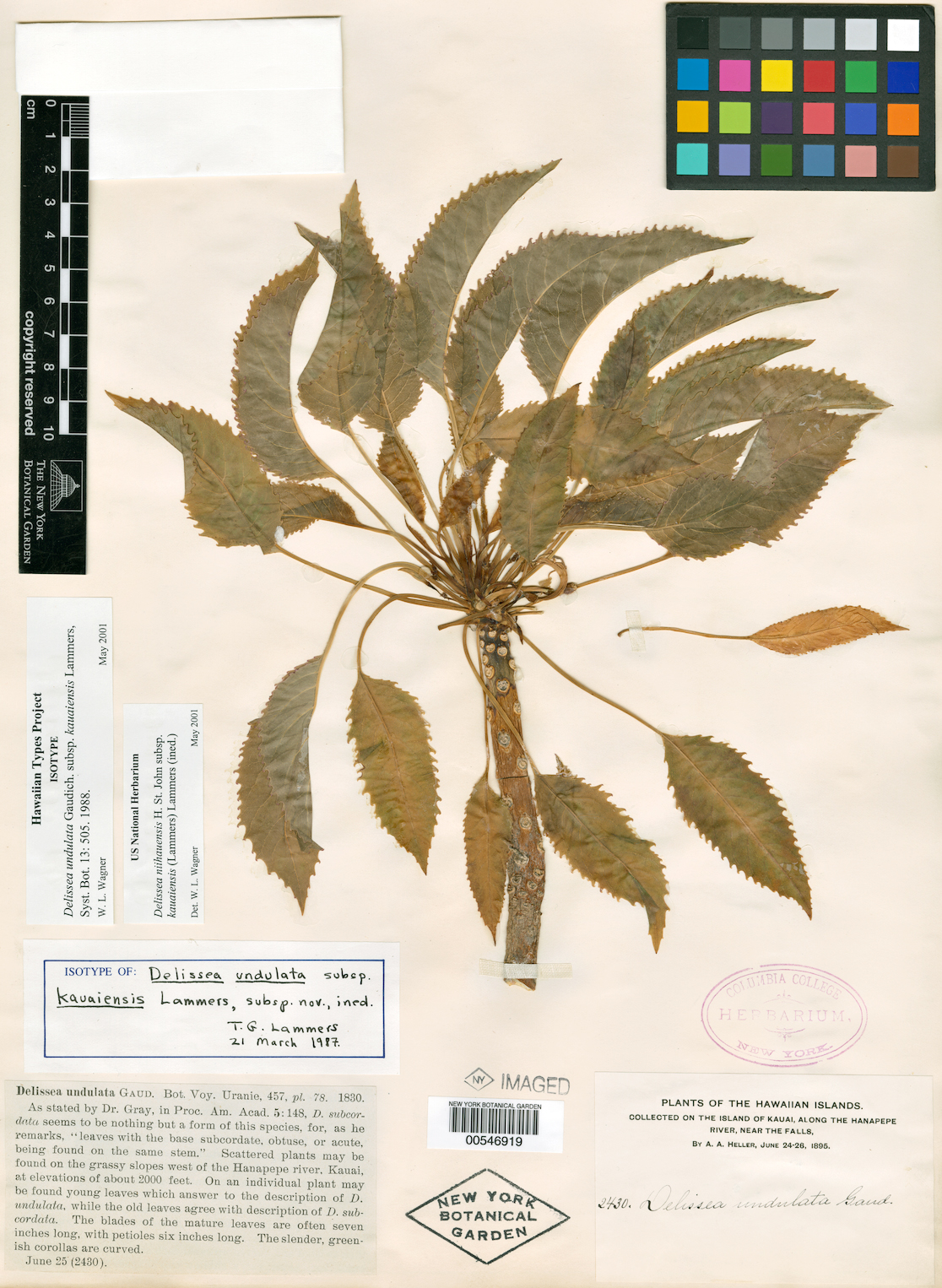

Most haunting, at least for me, was Patterson’s requiem to lost plants. Running through the center of the conservatory the artist placed a series of glass flowers inspired by pressed specimens of extinct plants that she had studied in NYBG’s William and Lynda Steere Herbarium during her yearslong residency. Part of the power of Patterson’s display was the sheer beauty of these lost plants, each like a movie star cut down in its prime. Among those she recreated were:

greensword, ‘ahinahina

Argyroxiphium virescens

Haleakala Crater, Maui, Hawai’i

Last seen: 1945

‘Ahinahina grew only on Maui, in the tropical high-altitude shrublands of the eastern slopes of Haleakala’s summit and Koolau Gap. Also known as greensword, it was part of a unique group of plants called silverswords that are found only on the Hawai’ian islands. These greenswords flowered only once every seven to fifteen years after a long lifespan. Having evolved with no protective mechanisms against grazing animals, its extinction has been attributed to the introduction of pigs, goats, and other livestock that decimated its habitat during a period of colonization.

leechleaf delissea

Delissea undulata subsp. kauaiensis

Kaua’i Island, Hawai’i

Last seen: 1895

Leechleaf delissea was a member of the bellflower family, with palmlike leaves and greenish-white, slightly down-curved flowers. It too grew only on the Hawai’ian islands, and was last collected along the falls of the Hanapepe River on Kaua’i in 1895. It is believed to have gone extinct both because of predation by black rats that arrived on colonizers’ ships as well as habitat destruction caused by the introduction of cattle and invasive plants that took root in its environment. The last known collection is housed in NYBG’s Steere Herbarium.

Palo Alto thistle

Cirsium praeteriens

Palo Alto, California

Last seen: 1901

The Palo Alto thistle, also sometimes called the lost thistle, was a flowering thistle notable for its long spines and soft, cobwebby stem. It was collected by an amateur botanist from a location in California identified only as “Palo Alto.” Although the botanist didn’t include much information about the plant’s habitat, contemporary scientists have theorized that the thistle grew in or near wetlands, given other native thistles’ propensity for wet feet. It has not been seen since it was collected in 1901, likely wiped out by rapid urban expansion that destroyed its delicate habitat. The specimen in NYBG’s Steere Herbarium is one of only two known samples in the world.

This question is important, particularly at a time when we are losing species faster than we are gaining them. The climate crisis, with its accompanying habitat destruction, is accelerating extinctions, threatening more than two million species globally. And this is just a rough accounting. Scientists have yet to document the Earth’s full biodiversity—an estimated 15 percent of the world’s species remain uncatalogued— meaning that the number of threatened and extinct species may actually be far greater. As Inger Andersen, Executive Director of the United Nations Environmental Program, has observed, “As far as biodiversity is concerned, we are at war with nature.”

For NYBG Education, Patterson’s exhibition provided a critical opportunity to teach children about this crisis in ways that were both palpable and compelling. For too many people, extinction is a concept that feels remote and abstract: it’s something that happens someplace else to someone else. It’s happening in rain forests of the Amazon, to the golden toads of Costa Rica, and once, long ago, to the dodo on Mauritius. Audiences don’t necessarily feel like extinction is happening here, now, to us, in the United States. To inspire action, we need to make the issue feel more relevant, more immediate, more localized— because the flora and fauna that we see today may not be here tomorrow unless we take action for their conservation.

For educators, the question is, how do we make this absence palpable? How can we position something that is absent as tangible—as tactile—in order to better teach the next generation to be good stewards of our environment? How do you teach a generation that has never seen, touched, felt, or smelled an extinct species not only to grasp but to care about the magnitude of the crisis? The ghost flowers of Ebony G. Patterson were an incredible opportunity to make the invisible, visible. Beyond just stunning works of art, Patterson’s ghost flowers were an invaluable object lesson about what we have lost.

To help children understand Patterson’s art and the extinction crisis that they represented, NYBG Education created specialized tours and workshops for schoolchildren and their teachers. For example, NYBG’s GreenSchool, which has operated for nearly 50 years from within the conservatory, beneath the desert houses with their sprawling aloes and flowering cacti, offered school groups a special “Challenge How You See” tour. This journey began by asking children and their teachers to reflect on the artist’s statement that “A garden is never merely a garden. A garden is a burial ground for history.” Starting on the lawn with the vultures (Patterson’s “cleansers of the earth”), children learned about ecosystems, about cycles of loss and regeneration, as well as decay, seasonal change, and the critical interactions needed to keep ecosystems healthy. Throughout, children were encouraged to write reflections in field journals in response to questions like:

What have you heard about extinction?

What have we lost?

What we still stand to lose?

In the house with lost plants, children were asked to “sit with the dead and learn from the dead.” “What could we learn from ghosts if we could talk to them?” “What can we learn from the plants that we have lost?” The tour acknowledged that “(w)hen the last living individual of a species dies and the entire life form is lost from Earth has always been part of the natural process.” Yet children also learned that typically this process happens slowly over time—over centuries or even millennia—whereas right now, extinction is accelerating. At the end of the tour, in the GreenSchool’s classrooms, children made their own physical manifestation of extinct plants out of clay, so that they could bring home tactile reminders of the plant stories they had learned, to feel connected and hopefully inspired to protect the plants of the world.

Perhaps even more significantly, Patterson’s exhibit provided an opportunity for NYBG to guide teachers on how to address issues of extinction within their own classrooms. Each summer, NYBG’s Professional Learning team offers an “Art of Science” course for third through twelfth grade teachers, primarily from New York City Public Schools, using the Garden to model outdoor education initiatives and nature-based learning strategies. In addition to meeting Next Generation Science Standards, these “Art of Science” courses are intended to help participants hone skills of observation and critical inquiry that they can then share with their own students as well as with teacher communities to advance science education more broadly. To help gain this wider reach, teachers are encouraged to invite friends and colleagues to their final project presentations: three-part lesson units on how to leverage cultural institutions like the New York Botanical Garden to teach children art and science.

For “… things come to thrive … in the shedding … in the molting,” teachers spent an intense week at NYBG learning about the artist and her practice as well as the plants, both living and extinct, that formed the core of the exhibition. Teachers sketched and journaled throughout NYBG, going “behind the scenes” at the Steere Herbarium and learning about the extinct plants that inspired Patterson’s ghost flowers. Notably, the “Art of Science” course covered Patterson’s exhibition as a whole; it was not exclusive to the extinction crisis. And because climate education is not yet included in Next Generation Science Standards, Patterson’s ghost flowers served more as a jumping off point for plant adaptations, which is included in the state curriculum, than extinction per se. Viewed through this lens, Patterson’s recreation of the ‘ahinahina became a means to spotlight an extraordinary plant journey. Likely descended from seeds that arrived in Hawai’i stuck to the feet of migratory birds, silverswords have persisted in high elevations despite shallow root systems that make them vulnerable to grazing livestock and wandering tourists. They are poached by plant collectors, outcompeted by invasive plants, and preyed upon by invasive species. Yet in 1989, botanists discovered hybrids of the lost ‘ahinahina and another closely related silversword, meaning some of this extinct greensword’s DNA survives, despite all the many challenges. Teachers were encouraged to use such plant narratives to teach children about resilience— in themselves, in the plant world, and our planet as a whole—to inspire hope that what we learn about the extinction crisis has the potential to guide our future, not just memorialize our past.

Today, botanical gardens, once founded to be living cabinets of curiosity, are havens of biodiversity. We preserve species; we speak for plants. Scientists may not yet be able to reverse the collateral damage of the so-called “Age of Exploration,” to bring back species from the dead like the ‘ahinahina of Hawai’i, the lost thistle of California, or the famous dodo bird. But we can better protect and steward the Earth’s remaining species—and teach the next generation how to do the same. To be successful in this mission, we need opportunities for object-based learning to make the invisible, visible and the absent, palpable. We need physical examples like the ghost flowers of Ebony G. Patterson so that children, teachers, and their families can better grasp that our Earth is a wonderland in need of our protection. To do this, we need audiences to look, really look at the extinction crisis. We need to give people tools to peel back their learned complacency in order to position the extinction crisis as relevant and immediate and connected to their own experiences. As Patterson has stated in interviews, the trick is to get people to look, not just see: “Looking requires thought, it requires engagement, it requires awareness, it requires inquiry, it requires presence,” the artist has said. Looking at Ebony G. Patterson’s ghost flowers in the Enid A. Haupt Conservatory, it was hard to ignore the absence of these extraordinary plants.

Kay Chubbuck is vice president for education at New York Botanical Garden.