This article inaugurates a new department, From the Archives, in which authors reflect on a significant article from Arnoldia’s backfile. To begin, we’re revisiting Sheila Connor’s “The Nature of Eastern Asia: Botanical and Cultural Images from the Arnold Arboretum Archives” (Arnoldia 63:3, 2005). Lisa Pearson uses Connor’s article as a springboard to reflect on digitization and its legacy of scholarship—a legacy which continues, as Pearson and her team in the Arboretum’s Horticultural Library rethink the collection for improved access and insight. Connor’s text is indicated in italics throughout.—Editors

Twenty years ago, as we approached the conclusion of our second Harvard Library Digital Initiative (LDI) grant, Sheila Connor, Horticultural Research Archivist and head of the Arboretum Library at that time, wrote in this publication about our efforts to catalog and digitize our collection of historical eastern Asian photographs taken by Arnold Arboretum collectors in the first quarter of the 20th century. These large projects cataloged over 5,200 historical images and a complementary collection of over 1,900 images taken by modern collectors from 1984 to 2000 in the same region of China explored by Joseph Rock from 1924–1927. These projects were major undertakings at a time when large-scale digitization initiatives were new territory. I had the honor of working on both as a young image cataloger, and over the past two decades, all of these photographs have become old friends whom I visit and revisit almost daily as I assist scholars with their research or fulfill image use requests. By digitizing these materials, we provided the catalyst to generate more scholarship about these photographs, which in turn has generated more scholarship, and so on. I feel like we have succeeded beyond our wildest dreams, and I look forward to the coming decades and what might be created in the future.

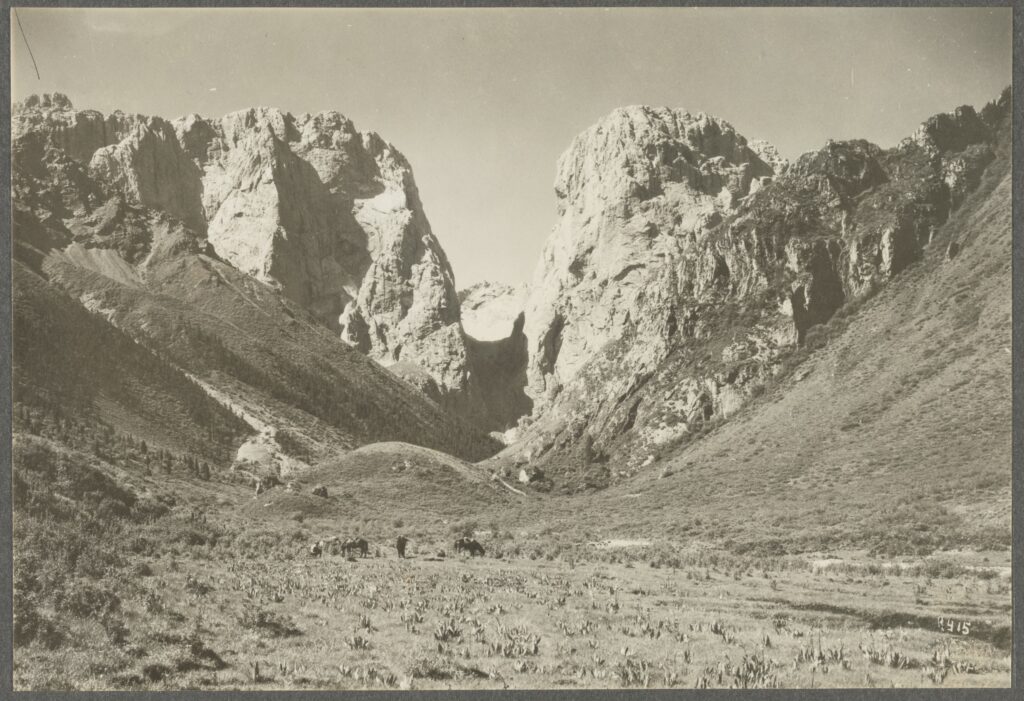

The Arnold Arboretum’s collection of eastern Asian photographs represents the work of several intrepid plant explorers who traveled to exotic lands in the early years of the twentieth century and returned with not only seeds, live plants, and dried herbarium specimens, but with stunning images of plants, people, and landscapes as well. We owe these images to the foresight of Charles Sprague Sargent, the director of the Arboretum during its first fifty years. In December 1906, when E. H. Wilson signed an agreement to collect in China for the Arboretum, Sargent set the precedent of asking all his explorers to document their expeditions with photographs: “A good set of photographs are really about as important as anything you can bring back with you,” he wrote. He would later urge William Purdom to “take views of villages and other striking and interesting objects as the world knows little of the appearance of those parts of China which you are to visit.” And to Joseph Rock, the last of the great explorers who would work for him, Sargent wrote, somewhat peevishly, “I don’t know how you got the idea that we didn’t want scenery. These are always important and interesting additions to our collection, and you may be sure you cannot send us too many of them.”

As an institution, we have long recognized the value of photographs for botanical research, which along with our living plants and dried plant specimens, form a “three-legged stool” of our collections, with each leg being of equal importance for scholarship. The Library began to collect and house dendrological photos long before Sargent directed Wilson to get a camera for his trip. The photos had been taken by staff members such as Alfred Rehder or John G. Jack to record plants on our grounds, or received, sometimes with plant material or correspondence, from collectors or botanists outside of the Arboretum community.

When we first proposed our participation in the LDI program, digitization was a brave new world, and institutions were more used to, and interested, in digitizing humanities related collections. We were told point blank that our photographs were “just trees” with the implication that they had less value than the more familiar fine arts collections that were being proposed for digitization. Part of our motivation for embarking on these two projects was the realization that the photographs actually included far more than “just trees.” They showed little-known landscapes of the far-flung locations, cultural objects—so many of which had been lost in the political and social upheavals of the mid twentieth century, objects of daily life and their uses by the Indigenous people, and the people themselves in regions our collectors explored.

All these visual riches had been trapped in their filing cabinets since they were created, only accessible onsite in the Horticultural Library reading room. Our historical filing system for these photos was by genus and species. If you wanted to see images of Abies koreana taken in Korea, for example, you went to the drawer and rifled through the contents until you came to that species. There were typed lists of the eastern Asian pictures but there was no card index (and certainly not an electronic spreadsheet or a database!) on which could have been noted potentially interesting details in the images.

Our first LDI project digitized a collection of photographs taken by Joseph Charles Francis Rock during his explorations in Gansu and Tibet from 1924-1927. We contributed over 600 photos from the Arboretum’s collection, which was augmented by an additional 246 ethnographic images from the Harvard Yenching Library. These were paired with a collection of 1,900 modern photographs from the same botanically diverse region of west central China taken by Arboretum collectors David Boufford, Susan Kelley, and Richard Ree from 1984-2000. The project also digitized a very large hand drawn map made by Rock of the region, digitized the type specimens Rock collected on this expedition, and created a gazetteer that correlated historical place names with their modern equivalents. Rock kept a detailed journal of his travels, and we extracted the relevant portions of his entries which describe the images. These entries flesh out the sometimes-laconic descriptions on the photos themselves.

The second LDI grant was even more ambitious in its scope and sought to digitize all our remaining eastern Asian photographs—about 4,600 in all. They included all of Ernest Wilson’s images from China, Japan, Korea, and Taiwan; an additional collection of photos by Jospeh Rock taken in 1922; a large collection of photographs by USDA (and Arboretum) collector Frank Meyer; a small but early collection of images taken by John Jack in Japan, Korea, China, and Taiwan in 1905; another small but ethnographically interesting collection of photos by William Purdom taken primarily in Mongolia and Gansu from 1909-1911; a collection of images by contract collector Joseph Hers; and a group of photographs by unknown and miscellaneous photographers.

John George Jack (1861–1949): 167 images (1905)

G. Jack was already experienced in plant exploration when he became the first staff member after Sargent to visit Asia. Jack had joined the Arboretum in 1886 and almost immediately began collecting and photographing plants in the U.S. and abroad. Between 1898 and 1900 he spent summers working for the U.S. Geological Survey, exploring and photographing the forests of Colorado and the Big Horn Mountains of Wyoming. In 1891, he visited botanic gardens and nurseries in England and on the continent, and in 1904, he and Arboretum taxonomist Alfred Rehder collected specimens in the western United States and in Canada. It is likely that his yearlong Asian journey was self-financed; although Sargent’s Annual Report for the Year Ending July 31, 1905, states that “Mr. J. G. Jack has started on a journey to the East to obtain material for the Arboretum in Japan, Korea, and northern China,” no record of the Arboretum underwriting this expedition appears in the archives. Jack’s introduction to an undated, unpublished manuscript entitled “Notes on Some Recently Introduced Trees and Shrubs” may explain why.…

“On the first of July, 1905, I left Boston for Japan[.] The object of my trip was primarily rest and recreation for three or four months, combined with a desire to observe some of the interesting arborescent flora of central and northeastern Japan … A short visit was also made to Korea and to Peking in China….”

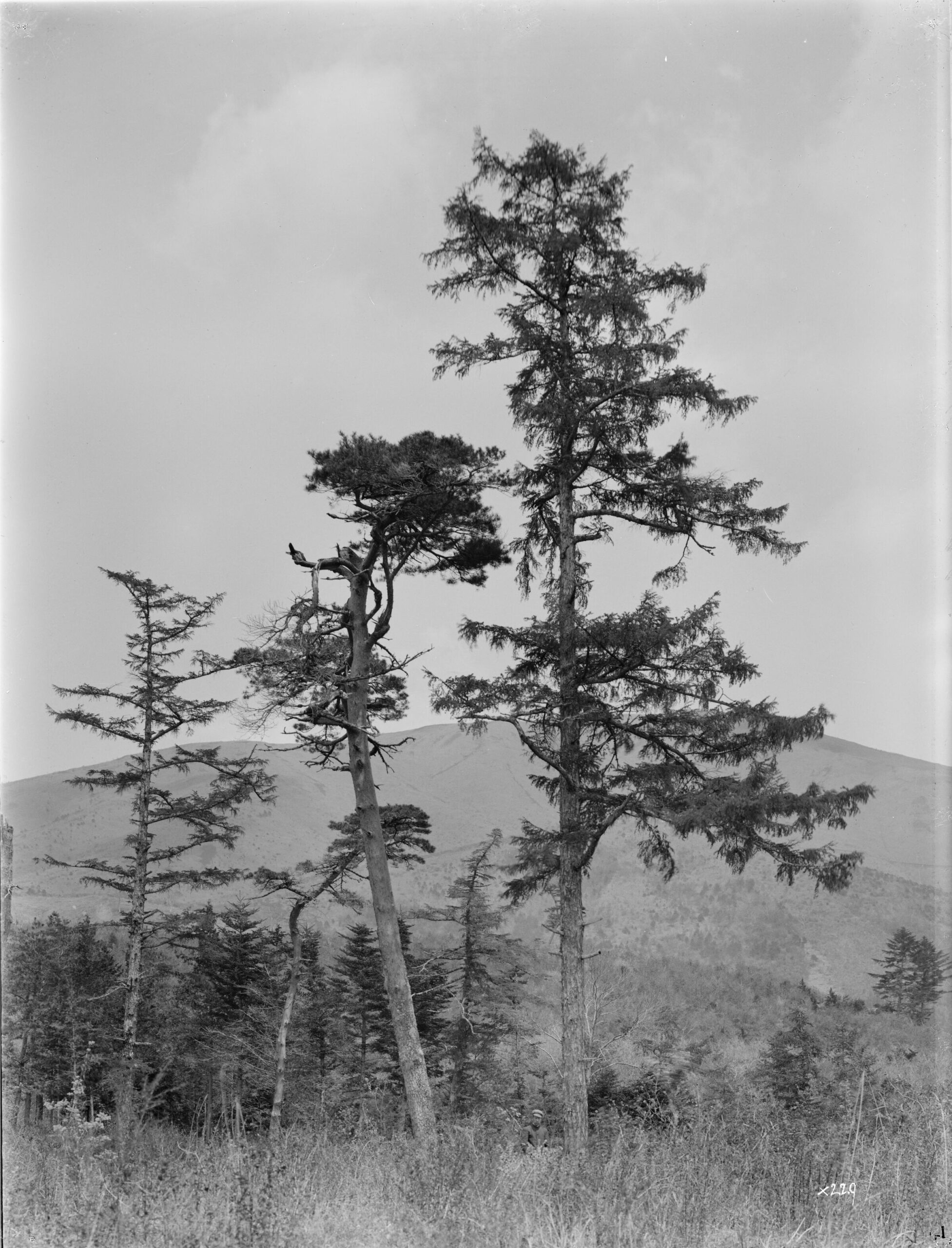

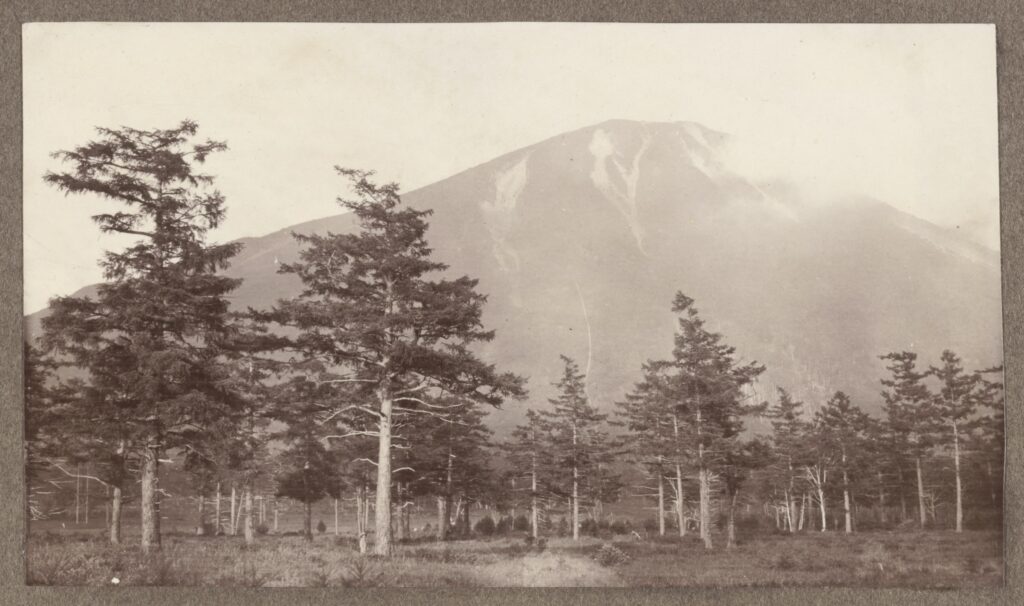

Forestry was a lifelong interest for Jack. Covering some of the ground that E. H. Wilson would later visit, Jack photographed the forest preserves around Mt. Fuji and elsewhere in Japan, as well as the forests of Taiwan and Korea. The scenes he captured in Beijing include formal portraits of people in traditional costumes.

In addition to herbarium specimens representing 258 plants, Jack returned with 171 images, many of them in a format especially useful for him—lantern slides. Jack had been appointed Harvard University lecturer on arboriculture in 1890 (the title was changed to lecturer in forestry in 1903) and he continued teaching throughout his career. In the fall and spring of each year he taught courses in dendrology to students and teachers using the Arboretum’s living collections as his classroom, and he taught forestry both at Harvard … and at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he also held a lectureship.

When we embark on digitization projects, we really have no idea what uses people might make of the images we place online, but by placing those images out there for anyone to see, we increase the awareness of a particular subject. The John Jack photographs, which we digitized in our second LDI grant project, are a case in point. In the early 2010s Jack’s granddaughter contacted us to say that she had a number of items that had belonged to her grandfather and would we like them. I unhesitatingly answered yes, and soon, we were in possession of a variety of items, including several versions of an autobiography, pocket diaries, and, extremely exciting for our photographic collection, an additional 200 photographs from his 1905 trip. The trip images, which Jack had donated to the Arboretum in 1935, and which we had digitized as part of the grant, could be characterized as being very businesslike and were almost exclusively of Japan. There were photographs of forestry stations and men engaged in forestry activities, those of lumber storage and

processing, and of trees “at home,” to use Wilson’s words, in their native habitats. The later donation rounded out Jack’s trip and allowed us to see some of fun that occurred in between those work-related visits. Excitingly the new collection contained more photos from the other legs of Jack’s trip, including his visits to Korea and China, as well as some sights on his return voyage through the Suez Canal and a

stop in Italy.

With the exception of an article I wrote for this publication in 2014, no additional scholarship has been generated around John Jack. This is unfortunate, partially because of his extensive contributions to the early history of the Arboretum in public education, for his plant exploration in the American West, and perhaps most important of all, his instruction of a generation of Asian botanists, including H. H. Hu, widely considered the father of Western botany in China.

Ernest Henry Wilson (1876–1930): 2,488 images

Born in England in 1876, Wilson received his training in horticulture at the Birmingham Technical College and at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. His career as an explorer began in 1899 when he traveled to China seeking the dove tree, Davidia involucrata, for the Veitch Nursery in England. A visit to the Arnold Arboretum on his way to China initiated a lifelong collaboration with Charles Sargent. As Wilson was preparing for his first Arboretum journey, Sargent insisted that he take along a large-format, Sanderson whole-plate field camera capable of recording both great detail and broad perspectives without distortion. The rest of his camera gear included a cumbersome wooden tripod and crates of heavy, fragile, 6 1/2-x-8 1/2-inch glass-plate negatives.

For three years Wilson explored western Hupeh [Hubei] and western Szechuan [Sichuan]. He returned to Boston in 1909 via … London, where he spent several months developing the glass-plate negatives and seeing for the first time his 720 images…. [H]is second Arboretum expedition, which began in 1910, was to collect cones and conifer seeds in the central and southwestern parts of China. In September of that year, while he was traveling between Sungpan and Chengdu [Sichuan], a landslide hit the expedition group, crushing Wilson’s leg. After several months in a hospital at Chengdu, Wilson returned to Boston in March 1911…. Before the accident, however, he had managed to take 374 images….

In January 1914…, Wilson sailed for Japan, where he would focus his attention on horticulture and cultivated plants including conifers, Kurume azaleas, and Japanese cherries. By the time the Wilsons returned to Boston at the beginning of 1915, there were 619 new images to add to the photograph collection. Wilson next undertook a “systematic exploration” of Korea. Beginning in 1917 with the Japanese islands and Taiwan, he then traveled along the Yalu River into the far northern reaches of Korea, returning to Boston in 1919 with seeds, living plants, 30,000 herbarium specimens, and 700 photographs. His last expedition, a tour of the gardens of the world, took place from 1920 to 1922 and included a stop at the Singapore Botanical Garden in June of 1921. Of the 250 images he shot during this journey, 15 were taken in Asia.

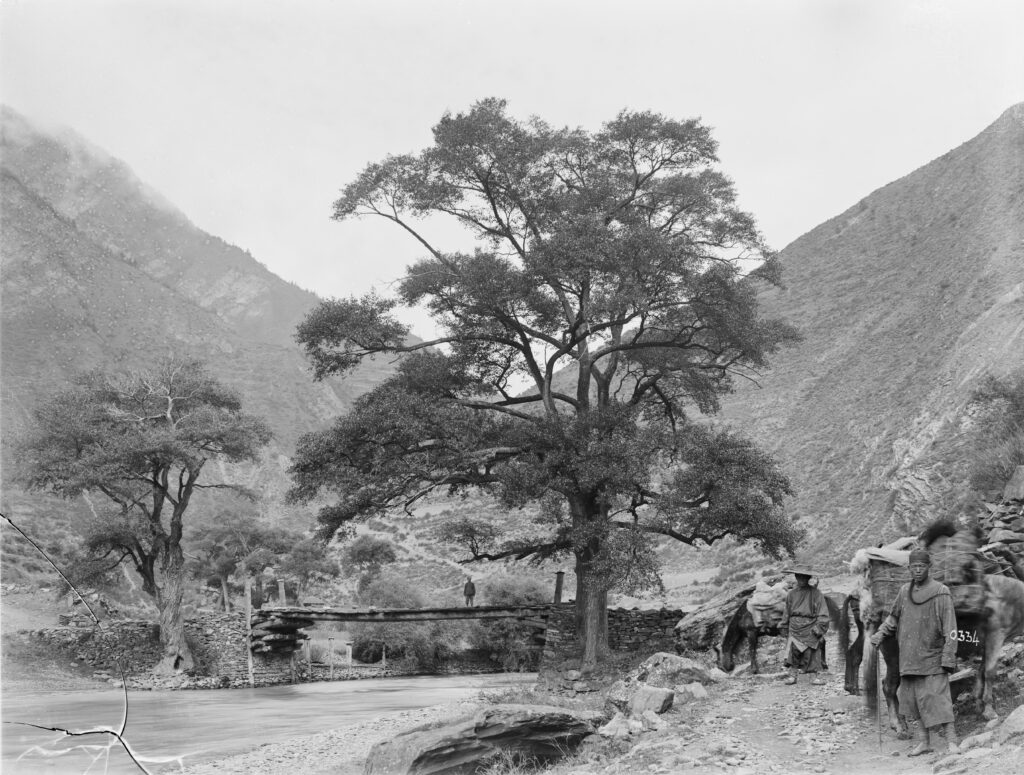

Wilson is rightly revered as the greatest Arnold Arboretum plant collector of our early years. His industry and productiveness are astounding, especially when we consider that much of his traveling in country in China and Korea was on foot in extremely rough country. In China, he relied on a tight-knit team of trained collectors, men from Yichang, Hubei Province, and its environs whom he had mentored. Some of the men might also have collected previously for Augustine Henry, the Irish botanist, who was attached to the customs service in China and directed Wilson in finding the Davidia tree during his first expedition for Veitch Nursery. Wilson relates the incident in 1907, upon his return to China, that having sent word ahead to Yichang of his impending arrival, one of his men, who had collected for him during his expeditions for Veitch, met him on the gangplank of his ship to say that his men had been reassembled. In 1910, he might well have died in the avalanche mentioned above had it not been for the efforts of the men of his team. They stabilized his injuries and splinted his badly broken leg with his camera tripod. Then they carried him for three days down from the mountains, even encountering a 100-animal mule train coming the opposite way, to the Friends Mission in Chengdu for medical treatment. While Wilson convalesced, his men returned to the field and collected seeds and bulbs from locations that had been identified during scouting earlier in the season. It is safe to say that this expedition would not have succeeded at all had it not been for the dedication of Wilson’s collecting team. In February 1911, just before he left western China for the last time, he photographed the men who had saved his life and his expedition. I think it is very telling the high regard in which he held them that he captioned the photograph, “My Chinese collectors, all faithful and true.” That said however, he didn’t provide their names! It would take another century and research by Professor Yin Kaipu as part of his Wilson rephotography project, to name two of the men. The bearded man third from the right was named Wang Tianguan, and the man fourth from the right had the family name Yin.

The injury Wilson sustained in Sichuan was severe. When he left China in February 1911, he was still on crutches and the trauma had cause his right leg to heal one inch shorter than his left leg. His next expedition would not come until 1914, and to save excessive strain it was decided that he should explore in Japan where the well-developed rail system allowed for much easier travel. One of his tasks on this journey was to document flowering cherries and try to answer some lingering taxonomic questions about the plants. Starting on the south islands, Wilson followed the blooming trees north. The results of his observations were published in 1916 in The Cherries of Japan.

Wilson is rightly revered as the greatest Arnold Arboretum plant collector of our early years.

Wilson’s 1917-1919 trip to eastern Asia was his most productive, concentrated primarily on exploring Korea, with sojourns in Japan and Taiwan. He spent the bulk of 1917 and half of 1918 traversing the length and breadth of the country and documented his travels with about 300 photographs taken with his Sanderson camera. He visited locations of great natural beauty such as the Geumgengsan or Diamond Mountains which today lies just over the North Korean border of the Demilitarized Zone. These photographs are particularly poignant because most of the religious institutions there were destroyed by bombing in the Korean War. His most rigorous time in the field was an extended exploration in far northern Korea in August and September 1917. During this time in the field, he traveled about 500 miles and much of that on foot. This area today is in North Korea and inaccessible to botanical exploration. Sargent’s admonition to William Purdom that he should photograph the landscape, “as the world knows little of the appearance of those parts of China (or in this case Korea) which you are to visit,” is particularly apt, because between war and the decades-long closure of North Korean society this area is terra incognita.

Re-photographing Ernest Wilson’s China

In 2008, the Arnold Arboretum Archives was approached by Professor Yin Kaipu to provide publication quality copies of about 250 of Ernest Wilson’s 1907-1911 photographs of Western China for a book1 that was to accompany a re-photography project he had embarked upon several years previously.

Yin, a retired professor of plant ecology from the Chengdu Institute of Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, is a staunch advocate of nature conservation who believes in the sustainable use of natural resources, and is working to preserve the biodiversity and ethnic culture of Western China.

His extensive travels in the region brought him to the same places that Ernest Wilson explored over 100 years ago, many of which he recognized when studying Wilson’s images! Upon his retirement, he began to travel the region to relocate more places that Wilson had photographed, eventually identifying over 250 separate locations. Yin, then conceived a project to re-photograph the places to provide a georeferenced record of 100 years of change in the area.

Yin Kaipu not only found over 250 of Wilson’s photography locations but also tracked down descendants of some of the people pictured, including several of Ernest Wilson’s collecting team, men who had assisted him since his expeditions for Veitch Nurseries from 1899-1905. Professor Yin is hopeful that several nationally broadcast television programs featuring his work will encourage more people to come forward who might recognize their ancestors in the photos.

Yin’s photographs show a landscape which has modernized and become more populated but also revealed areas which have benefited from recent reforestation programs. Perhaps more importantly, he also created a pictorial record of the landscape prior to the devastating earthquakes in the region in 2008 and 2011 which radically reshaped the landscape in many places. Professor Yin has since returned and re-photographed these locations, adding GPS positioning, so that in another 100 years, scientists can return and again re-photograph the exact locations.

We included 15 photographs from Wilson’s 1920–1922 “Tour of the Gardens of the World” that were taken at the Singapore Botanic Garden because they were taken in temperate Asia. We did not include any other images from this trip because Wilson primarily visited tropical areas. The title of this trip was rather misleading. Margaret Grose, who has studied and written about this expedition extensively, characterizes it as a good will tour to the British Dominion countries which (with the exception of Canada), it was. Her research revealed Wilson concerns with forestry and conservation in the countries he visited and has given us a far greater and more nuanced understanding of this journey.

Wilson’s photographic legacy has generated the largest amount of scholarship by far since we engaged in our two LDI projects. They prompted Yin Kaipu to begin his rephotography project which has identified about 300 Chinese locations that Wilson photographed 100 years earlier (see sidebar). The photographs have also led to an increased awareness of Wilson’s published works amongst Chinese scholars, in particular the monumental China Mother of Gardens, which has led to at least three translations2 or partial translations of the work. Wilson’s explorations in Sichuan have generated much local interest in the region. In Wilson’s beloved Songpan, the city has erected a large, engraved-stone mural of his panoramic photographs of the town that he took in 1910. I had the honor to visit there in 2017 to lecture on his photographs and had the pleasure of seeing this striking landscape for myself. I recognized a number sites, including the imposing Populus suaveolens in the photograph above.

Frank Nicholas Meyer (1875–1918): 1,310 images

In 1905, the United States Department of Agriculture’s Office of Seed and Plant Introduction recruited Frank Meyer, a native of Holland who had immigrated to America in 1901, to gather economically useful plants in China. Through an arrangement worked out between Sargent and David Fairchild of the USDA, Meyer was to send to the Arboretum trees and shrubs of ornamental value along with images of his travels. The photographs in the Meyer Collection document his four expeditions to western China and Manchuria. Unlike Wilson’s highly composed photographs, Meyer’s images have an immediate and spontaneous quality, perhaps because they document daily life in this remote region: farmers and other people going about their work, manufacturing techniques, and markets were all captured through his lens. Even his images of plants often include local people or architectural backgrounds.

Meyer and Wilson corresponded occasionally, trading information on routes, travel conditions, and collecting strategies. Occasionally their letters touched on personal matters. In a letter from Beijing in 1907 Meyer wrote, “This roaming about, always alone, takes lots of energy away from a fellow, don’t you agree with me too, in this respect?” On June 2, 1918, Meyer disappeared from a steamer and although his body was eventually recovered, the circumstances of his death remain a mystery.

Frank Meyer’s photographs primarily reflect his main assignment in Asia for the United States Department of Agriculture, to collect plants of economic value that could be grown profitably in America. He understood that many of the plants were entirely new to Western audiences and as such, he devoted much effort to document the uses that the local people had for a variety of food products and building materials. He took pains to write detailed descriptions of the preparation of different dishes, such this one for mung bean sprouts that accompanied the lower photograph above, “A cart full of tubs of bean sprouts, produced by the humble mung bean. These bean sprouts are eaten as a vegetable, when scalded, and they are a very tasteful product when served cold as salad with some soy-bean, vinegar and oil sprinkled over them. Sixteen or seventeen catties of dry beans supply from fifty to sixty catties of sprouts.” Meyer’s photos were taken with an inexpensive snapshot camera which allowed him to be spontaneous and very much in the moment. His image of boatmen on the Huang Ho clad only in loincloths has an almost sculptural quality as the men lean into their work. He describes the scene thus, “On the Huangho, near Chao yi, Shansi. Incidents of travel. On the Yellow River, being in the deep water now where the boats float down with the current. Only paddling is practised now in the shallow places the boat is pulled by 8 or 10 men. These hard working fellows earn only two taels per month (U.S. gold $1.70) and receive board and lodging, but what a board and lodging!”

“Meyer’s images have an immediate and spontaneous quality, perhaps because they document daily life.”

William Purdom (1880–1921): 161 images (1909–11)

In 1909, with Wilson about to return from southern China and the agreement with the USDA in place to ensure that Frank Meyer’s Asian collections would be shared with the Arboretum, Sargent was eager to dispatch yet another plant collector to the largely unexplored northeastern provinces of China. Hoping, in Sargent’s words, to “bring into our gardens Chinese plants from regions with climates even more severe than those of New England,” William Purdom—the most inexperienced of Arboretum explorers embarked on his first expedition in February of that year…. For three years the shy and retiring novice followed the Yellow River north, his work always overshadowed by, and his meager results compared to, the successful exploits of the gregarious, prolific Wilson. His collection techniques improved, however, and he is now known for his later successes, when he worked with Reginald Farrer. Eventually he accepted a post as inspector of forests for the Chinese government. He must have been glad to be relieved of Sargent’s exacting photographic demands, for although he never complained to Sargent himself, in 1909 he wrote to Veitch: I am not a specialist at photography and do not wish to infer that my camera is not a good one but I do now believe that a camera to carry on one’s back with films is the most serviceable thing out here on these rough roads for it is nearly impossible to carry the plates. No end of mine got smashed.

Much to Charles Sargent’s annoyance, William Purdom made fewer plant collections than Ernest Wilson, but it wasn’t for lack of trying; he initially was instructed to collect in northern China, an area that Sargent was convinced was covered in trees but had been largely denuded of forests. He found success in his collecting in Shaanxi Province however, locating a wild form of tree peony, later followed by a period of botanizing in Gansu Province. The second leg of his expedition was hampered by political unrest however and he had a narrow escape from Gansu.

Although he complained about breakage of his plates, from an ethnographic perspective, Purdom’s expedition was extremely successful. He proved a gifted portraitist, capturing for posterity a rich record of the peoples of Tibetan border region. Unlike Wilson, he had taught himself some Chinese so he might have been able to put his subjects more at ease for their photos. The Arboretum holds 173 prints of his photographs in our collection. About 35 of the original glass plate negatives from his Arboretum expedition are held in the British Library, along with over 200 nitrate film negatives from this expedition and possibly also from his expedition with Reginald Farrar.

When we digitize images and place them online, it is with the hope that they will generate scholarship and thus increase our knowledge of our own holdings. Purdom’s photographs have done that beyond our wildest dreams. He has been the subject of three full length biographies, one by botanist and plant collector Alistair Watt,3 one by independent researcher Francois Gordon,4 and the third by independent researcher O. V. Presant.5 All three biographies dovetail well, Watt’s concentrates on a botanical perspective, Gordon’s on the sociopolitical world of Purdom’s expeditions, with Presant’s giving a good overview of his career.

Joseph Hers (1884–1965): 63 images (1919, 1923–24)

It was Hers, a railroad engineer and administrator of the Lung-Hai and Pien-Lo railways, who approached Sargent with a proposal to collect. specimens for the Arboretum. Stationed in Chengchow, a city on the Huang Ho River that had become an important railroad center thanks to its position at the junction of the Longhai (east-west) and the Beijing-Guangzhou (north-south) lines, Hers was superbly situated, with a job that enabled him to range far and wide collecting plants.

… Hers offered to send “seeds, or cuttings, or photos.” After he had done so, Sargent wrote him that “this is one of the most important collections of Chinese plants which has been sent to the Arboretum and I am extremely obliged to you for sending it to us.” Although we have only 63 of his images, Hers went on to collect seeds and specimens of more than 2,000 species, most of them sent to the Arnold Arboretum.

It is probably appropriate that Joseph Hers should follow William Purdom in this review of Arboretum plant collectors because he and Hers were colleagues in the Chinese rail service when Purdom was working on reforestation along the lines in the later 19-teens. Unfortunately, there has been only a small amount to scholarship generated from our placing Hers photographs online, but his living legacy at the Arnold Arboretum is still strong. There are 59 plants growing on the grounds that were grown directly from seed received from Hers or from repropagations of original Hers plants. Perhaps a scholar in the future will take inspiration from our images and take up Hers cause.

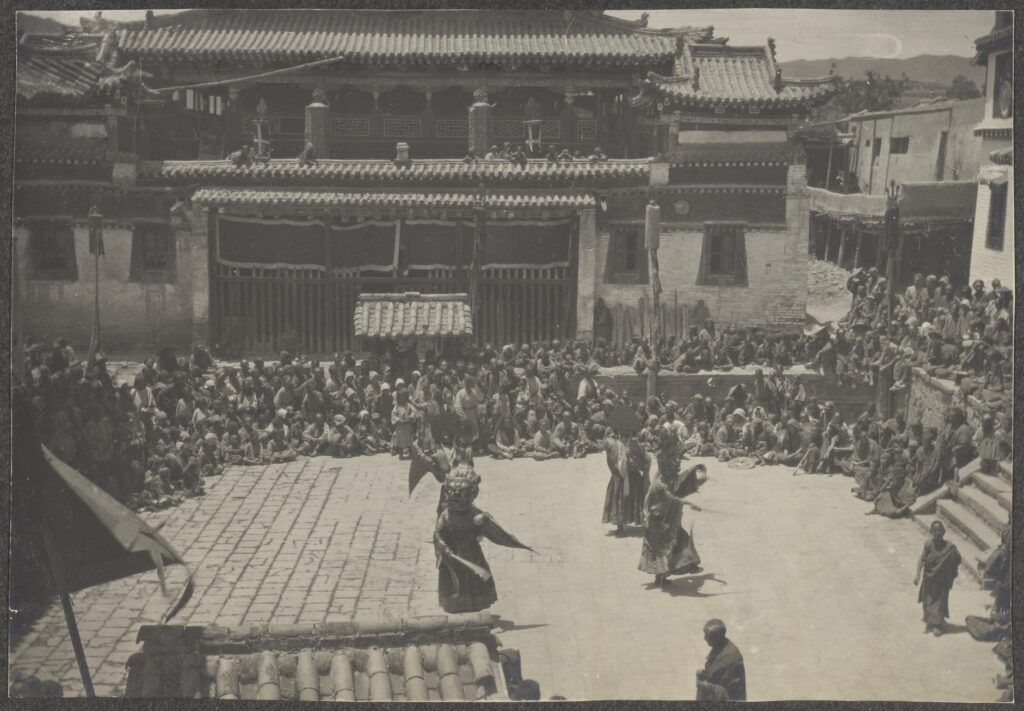

Joseph Charles Francis Rock (1884–1962): 320 images (1920–22)

Botanist, anthropologist, explorer, linguist, and author, Rock was the last of the great plant hunters employed by Sargent, who by then was elderly. Rock had immigrated to the United States from his native Austria in 1905, but between 1920 and 1949 he lived in China for extended periods, exploring, collecting plants and animals, and taking pictures for various United States agencies and other institutions, including The National Geographic Society, the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the Arnold Arboretum. He is still remembered by the older villagers in the city of Lijiang, which was his home base for many years. The 653 photographs that Rock took during the Arboretum’s 1924-27 expedition have already been digitized and are available on the VIA website; the remaining 320 photographs document his 1920–22 expedition to Thailand, Myanmar, and the Yunnan Province of China and include images of plants, landscapes, villages, architecture, and the ethnic minority peoples of the region.

Joseph Rock was a larger-than-life figure in a field and place that seemed to attract such people. He always seemed to have multiple irons in the fire, for multiple employers, an activity that came to annoy Charles Sargent no end. Rock was a dedicated diarist and for our first LDI grant, we paired his photos with relevant extracts from his journals. He also left a diary from his 1922 expedition to Yunnan, and we hope in the future to add quotes from that journal to that collection of images.

Professor Yin has begun another rephotography project, this time to seek out and rephotograph locations from Rock photos as he did for Ernest Wilson. This is not the first project of this kind for Joseph Rock images, however. Robert K. Moseley, a conservation ecologist formerly from the Nature Conservancy, tackled the subject two decades ago. His book Revisiting Shangri-La6 documents changes in the land in Yunnan and Gansu in the country Rock explored in the 1920s.

Tangential, because the project was not directly driven by our digitization projects, is Hartmut Walravens’ program to publish Joseph Rock’s correspondence and other writings. I am hopeful that Walravens’ most recent volume, which concerns Rock’s 1922 expedition in search of chaulmoogra oil (used for the treatment of Hansen’s Disease), will be helpful for enhancing the catalog records for this expedition.7

In light of the extensive use all these photographs have received by scholars worldwide over the past several decades since we placed them online, we have come to the realization that we need to recatalog this valuable collection to further increase its visibility and utility. Last year, I wrote a National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) grant which received excellent reviews but because of governmental cuts was not funded. We then approached a donor who funded a portion of the project.

Recataloging this collection will incorporate scholarly discoveries such as those mentioned above. Professor Yin’s research will be particularly helpful, especially for identifying geographical locations for the Wilson photos from China, as will the biographies of William Purdom, and the collected writings of Joseph Rock which are being published by Hartmut Walravens.

Through content that will contextualize the times and places, we will be able to publicly confront and explain our institutional role in colonialism of the period and in particular our engagement with Japanese occupation forces in Korea and Taiwan. It will also allow us a platform to formally acknowledge the contributions of the indigenous and local people our explorers encountered, interacted with, and employed on their expeditions. In some cases, it gives us a chance to put a newly learned name with a face.

In the decades since our materials were first placed online, botanical nomenclature has evolved and our institutional interest in conservation status has increased. We will update the former and include for the first time the latter, as well as recording any crop wild relatives for the plants. To prevent these data becoming outdated, we will also create procedures for conducting periodic updates to the records, as we do for all of the plants in our living collections.

The Arboretum Library staff receives requests for use of these images on at least a weekly basis and sometimes daily. They have been featured in books and online, but they have also been exhibited in museums across Asia. Recently, we provided 60 image files to the Xie Zilong Photography Museum in Changsha, Hunan for their exhibition, “Between Nakhi and Tibet: Joseph Rock’s Ethnographic Photography in China.” Since its opening in November 2024, the show has attracted over 70,000 visitors and its run has been extended until 2027.

We did not know what might become of these photographs when we placed them online. They might have just sat there, unappreciated, but instead they have been discovered by scholars, scientists, historians, and others and used to increase knowledge about an eventful period in Asian history. I have been amazed by the variety of uses they have received and have personally grown from my interactions with their users. I hope that our upcoming recataloging project will prepare this popular collection for another quarter or even half a century of intensive use and I look forward to all the new knowledge that will be generated.

Notes

- Yin, Kaipu. 2010. Tracing one hundred years of change:

Illustrating the environmental changes in Western China.

Beijing: Encyclopedia of China Publishing House. - Wilson, Ernest Henry, and Zhiyi Bao. 2017. Zhongguo nai

shi jie hua yuan zhi mu = China, mother of gardens. 第1版.

Beijing: Zhongguo qing nian chu ban she. Wilson, Ernest

Henry, and Qiming Hu. 2015. Zhongguo, yuan lin zhi mu =

China, mother of gardens. Guangzhou: Guangdong ke ji chu

ban she. Wilson, Ernest Henry, Yin Hong, and Wenqing

Gan. 2009. Weierxun Zai Aba : 100 Nian Qian Weierxun Zai

Sichuan Xi Bei Bu Wenchuan Maoxian Songpan Xiaojin Lu

Xing You Ji. 第1版. Chengdu: Sichuan min zu chu ban she. - Watt, Alistair, and Seamus O’Brien. 2019. Purdom and

Farrer: Plant Hunters on the Eaves of China. [Place of publication

not identified]: Published by the author. - Gordon, Francois. 2021. Will Purdom: Agitator, Plant-

Hunter, Forester. Edinburgh: Royal Botanic Garden

Edinburgh. - Presant, O. V. 2019. A perfect friend: the life of Cumbrian

plant hunter William Purdom / O.V. Presant. Hayloft Publishing

Ltd.

6 Moseley, Robert K. 2011. Revisiting Shangri-La: Photographing

a Century of Environmental and Cultural Change

in the Mountains of Southwest China. 第1版. Beijing]: China

Intercontinental Press. - This book is coming in the mail and is not yet in Harvard

collections.

Lisa Pearson is head of the library and archives at the Arnold Arboretum.