W. Wyatt Oswald investigates an ancient tree lost to an invasive insect.

My heart sank when I saw the pile of bark at the base of the tree. I knew its demise was inevitable, yet finding the tree dead still brought a sense of sadness and loss. I called it MHB-4, an underwhelming codename for an overwhelming tree. It was a majestic eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis), growing on a rocky slope above a small stream called Meeting House Brook (i.e., MHB), on the west side of the Middlesex Fells Reservation, a large piece of conservation land not far from Boston.

I had been aware of this sizable—65 cm (~26 inches) in diameter—and presumably old tree for 15 years or so. Like thousands of other people, I first encountered the hemlock when I walked within a few feet of it while hiking the Skyline Trail, a challenging path that circumnavigates the western half of the Fells. I suspect that many hikers walked past MHB-4 without paying much attention, lost in conversation or engrossed in thought or a podcast. Others, though, including folks with an interest in natural history or ecology, or just an appreciation for great big trees, would have felt some surge of emotion—awe, respect, admiration, joy—when they came upon this stately hemlock.

I experienced all of those emotions, but as a scientist with an interest in the long-term history of New England forests, the main reaction I felt upon encountering MHB-4 was curiosity. I wanted to learn more about this stunning tree, its neighboring hemlocks, and their experiences over the past decades and centuries. So, after visiting the tree periodically over ten years or so, I requested a research permit from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, and I returned to Meeting House Brook in 2016 with my student Jinghan Zhu, then an undergraduate at Emerson College, and my daughters Alta and Piper, ages nine and seven. We were armed with a forest-ecology tool called an increment borer, a metal tube with sharp threads at one end and a stiff handle at the other; it collects a cylindrical core of the wood, approximately the diameter of a chopstick, from near the base of the tree.

The trees were old, and probably among the oldest trees in eastern Massachusetts.

We took turns with the borer, rotating the handle clockwise as we cored inward, trying to hit the bullseye—the innermost annual rings, grown at the beginning of the tree’s life. For MHB-4 and its neighbor MHB-5—even larger at 71 cm (~28 inches) in diameter—the centers of the trees were rotten, so I wasn’t able to determine their years of establishment. But for the outer portion of the core, which hadn’t rotted, I glued the sample into a wooden tray, sanded the wood smooth with progressively finer sandpaper, then counted and measured the annual rings under a microscope.

For MHB-4, I counted and measured 116 tiny tree rings in the outer, unrotten 15 cm (~6 inches) of wood. The MHB-5 core was 19 cm (~8 inches) long and comprised 162 annual rings. Thus, the trees averaged about eight years of growth per centimeter for those sections of core. Extrapolating that rate of growth inward, through the rotten centers of the trees, yields establishment dates of around 1750. However, figuring the rates of growth slowed as the trees aged and began to compete for sunlight with neighboring trees, it seems likely that the trees established a bit later, perhaps around 1800. In any case the trees were old, and probably among the oldest trees in eastern Massachusetts, an area of young forests given its land-use history—deforestation by European colonists in the seventeenth century, widespread agriculture until the mid-nineteenth century, and heavy use of any remaining woodlots. MHB-4 and MHB-5 came through the 1800s unscathed, presumably because the slope above Meeting House Brook was too steep and rocky for the cultivation of crops and, at the time, the trees were too small to be worth harvesting. Then, in 1894, the Fells and its trees were protected as part of the Metropolitan Park System.

Despite this protection from logging, MHB-4 faced various stressful events over its long life, including regular windstorms and multiple droughts. Hemlocks like moist soils, so it’s likely that periods of low precipitation will be recorded in the pattern of wide and narrow tree rings. Indeed, particularly thin rings, marking hard times and reduced vigor, occurred in the MHB-4 core during the regional drought of the mid 1960s and again during the drought and coincident outbreak of spongy moth in the early 1980s.

The tree rings of hemlock MHB-4 began to narrow again around 2013. This is, unfortunately, when the hemlock woolly adelgid (HWA) arrived at Meeting House Brook. HWA is a tiny, aphid-like insect native to Asia, introduced to the mid-Atlantic region in the 1950s. The insect reproduces quickly and disperses readily, enabling it to spread rapidly across the eastern U.S. over the last several decades. HWA feeds on sap at the base of hemlock needles, the needles die when deprived of nutrients, and with reduced photosynthesis a tree will die within 5–15 years. When we sampled the Meeting House Brook hemlocks in 2016, I could tell that HWA was present as I saw its cottony white ovisacs clinging to the foliage on the bottoms of the branches of MHB-4, MHB-5, and other hemlocks in that stand.

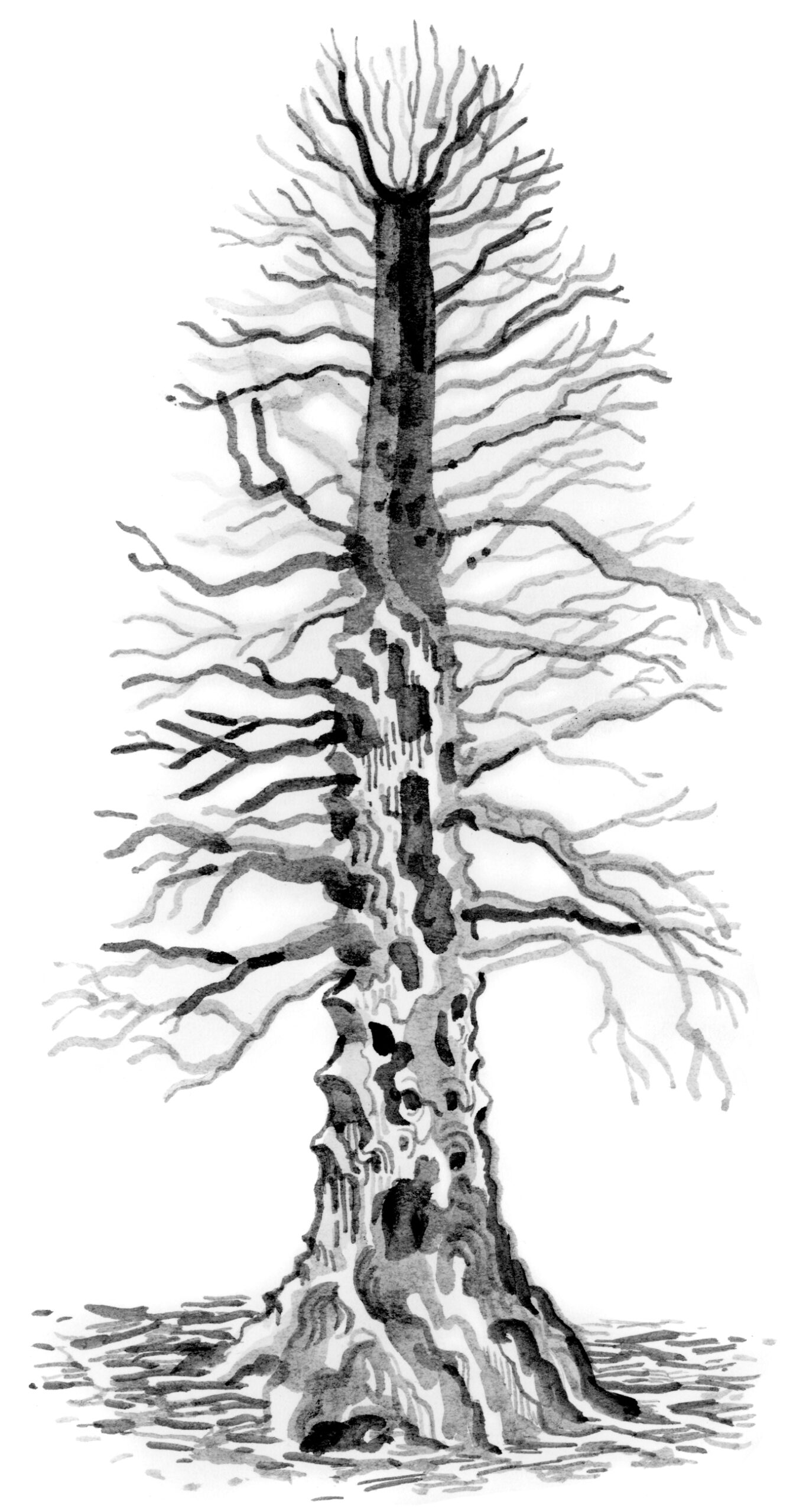

MHB-4 hung on for around ten years, aided by occasional drops in HWA populations during cold winters. But the tree eventually succumbed, losing fine branches and bark as it died, leaving the skeletal form I would encounter on my recent visit to Meeting House Brook in June of 2023. Tragically, this will be the fate of hemlocks large and small throughout the Fells, including MHB5, and eventually across the species’ entire range. Now is the time to learn as much as we can about the ecology of eastern hemlock, to delight in these wonderful trees while we still have the chance, and to honor them when they pass away.

W. Wyatt Oswald is an environmental scientist and professor in the Marlboro Institute for Liberal Arts & Interdisciplinary Studies at Emerson College.