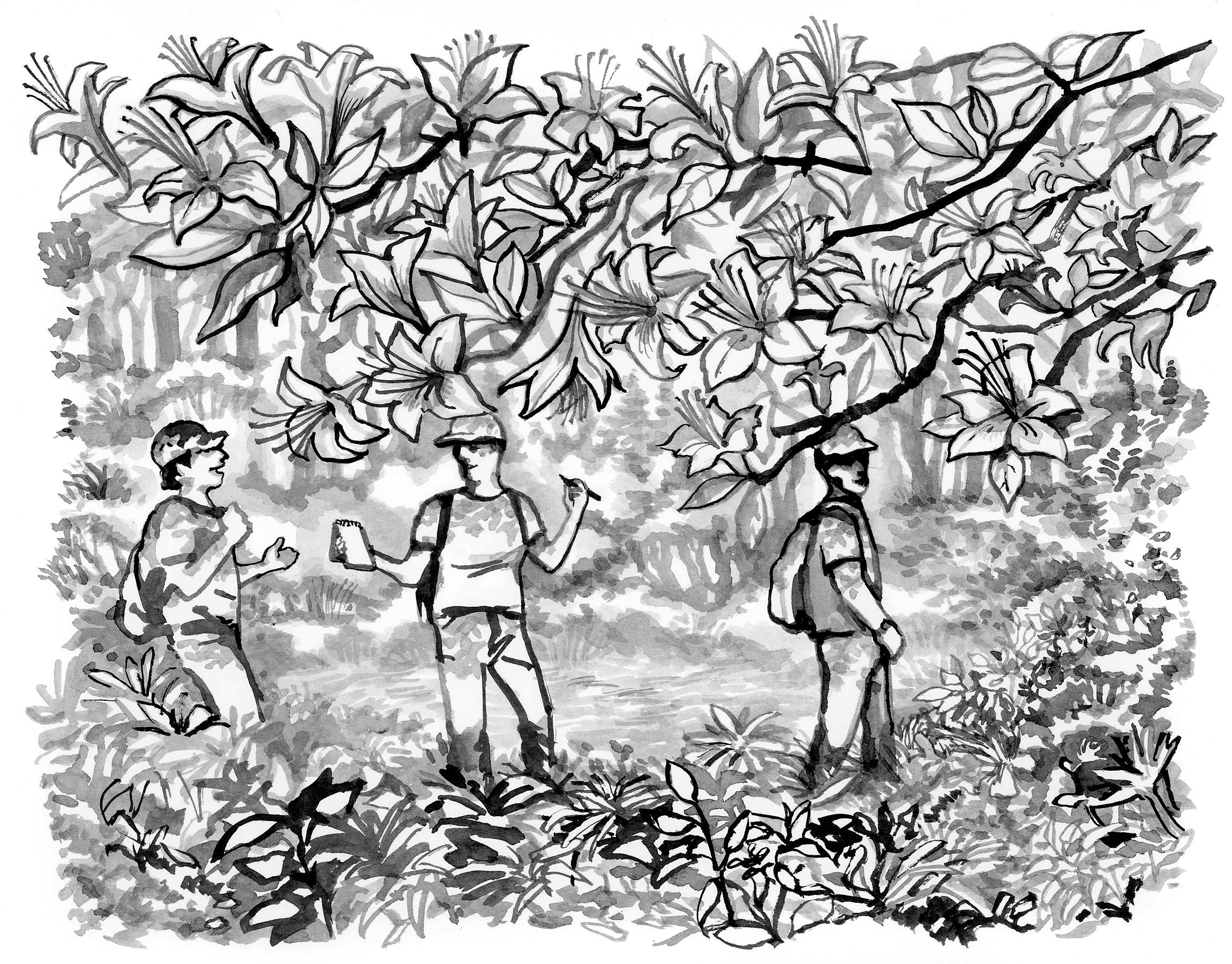

Connor Ryan scouts Rhododendron prunifolium along the Georgia-Alabama state line.

Few people would choose to travel to the deep South in August—the bugs, heat, and humidity are simply no fun. But if you wish to see one of North America’s most uncommon azaleas in bloom in the wild, that is when you must go. As part of an ongoing project to modernize the Holden Forests and Gardens rhododendron and azalea collection, we embarked on a trip to scout the plumleaf azalea (Rhododendron prunifolium) during the week of August 7–11, 2023.

The plumleaf azalea is one of the rarest rhododendron species in North America, occupying just a small area on either side of the Georgia/Alabama border along tributaries of the Chattahoochee River. In addition to being rare, it is a worthwhile garden species, one of very few native azaleas to bloom in July or later. Flowers are typically orange-red and tubular, favorites of swallowtail butterflies and hummingbirds. And the species is deceptively cold hardy, surviving and blooming following temperatures below -20° F with ease. Our program at Holden Forests and Gardens’ David G. Leach Research Station also has ties to the species. David Leach received seed from S. D. Coleman, the pioneering nurseryman from Fort Gaines, Georgia, for whom the Red Hills azalea (Rhododendron colemanii) was named. In respect and gratitude to Coleman, David named a selection of plumleaf azalea in his honor, and we have the original 1951 plant still in our collection.

The plan was to meet up at the Atlanta airport. Our team was comprised of me and Jing Wang, both from Holden Forests and Gardens, and Trevor Schulte, horticulturist at Morris Arboretum and Gardens. I had a list of historic sites we had permission to visit, and our plan was to get to as many as possible. We simply wanted to make a rough accounting of their health and size, and collect observations that could inform whether we might return to collect seeds.

To orient ourselves at the beginning of the trip, we spent Monday morning at Providence Canyon State Park, the most famous site to see the plumleaf azalea. It is so well-known that the azaleas and canyons are the image for the Georgia U-Haul. There are indeed thousands of plants there, with the classic red-orange flowers dotting the steep slopes and sides of streams in the park.

We spent the rest of the week tromping through the woods, wading through shallow streams, and keeping our eyes peeled for the orange-red flowers suspended at about shoulder height or higher. Our first stop on Tuesday was to be the River Bluff Recreation area operated by the Army Corps of Engineers just across the bridge from Eufaula, Alabama. We were dismayed to find a large, orange “Road Closed” sign across the entrance, so we continued to our next site, just a bit south. While there, I made a call to our contact at the Corps of Engineers, Sarah Jernigan. She said the bridges into the site had been condemned, and she pointed us in the direction of a local man named John Pritchett. John would later become an essential element of our story.

After successfully finding the azaleas at the current site, including a plumleaf azalea easily over twenty feet tall, we stopped for gas back near the River Bluff area. A booming and persistent late afternoon thunderstorm left us stranded in a gas station parking lot hoping the storm would reside. Finally, after 45 minutes, there was a gap in the radar, the rain had lightened, and we took our chance. We headed to our last site of the day, a stream-accessed roadside in northern Quitman County, Georgia.

I called John on Thursday, and he met us at River Bluff that afternoon. John, who as far as I could tell had no official connection to the county outside of a stint as school superintendent some years ago, had an incomprehensible amount of sway, allowing us to access the River Bluffs area after all. He was responsible for the “Road Closed” sign being erected. It turns out John was a fan of the plumleaf azalea and had an intimate knowledge of nearby populations. When we met, John led us to the River Bluffs population, telling us how he had shown Sarah this population as well and that it was just along the stream running through the park. He let us go off into the wooded stream to poke around.

How extensive would a collection need to be to capture the genetic diversity of the species?

While walking with John, we discussed other sites nearby—Bustahatchee Creek, Cool Branch, a spot off Highway 39 on land owned by local conglomerate W. C. Bradley. We mentioned a run-in with the police a couple days prior, when we stepped out of the woods only to find blue flashing lights pulled behind our white, mid-sized SUV with a Florida plate. After explaining to the officers that we were just looking for plants, and after they explained that I did a terrible job parking our car and that someone reported it abandoned, we were on our way back to our evening accommodations. When I told this to John, his eyes lit up, and he smiled. John then revealed to us that it was he who had called the cops. John lives at the end of the road we parked along. At this point we all cackled at the coincidence.

After further discussion about plumleaf azalea populations, John pulled out the holy grail: a 1988 report by James R. Allison from the Georgia Department of Natural Resources documenting every known population of the plumleaf azalea. I asked John where I could get a copy. He said, “Give me your address, and we’ll mail a copy to you.” I did, and a week later the report showed up at my house.

While habitat destruction by humans seems always to be a key component in the demise of many species, deer and wild boar may be the greatest threat to the plumleafs. Many plumleaf azalea populations I have visited (around 15 at this point) have been spared from logging and other habitat destruction due to the ankle-breaking slopes and streams on which they reside. This tracks with the report John shared with us, which states “that R. prunifolium is a species not in the least threatened with extinction within the foreseeable future.” In our time down south, we noted that invasive species were uncommon in the core of the populations we visited. Deer, however, prevent the plants from regrowing, leaving only the oldest, mature stems to persist until they can no longer. We saw plant after plant with new shoots chewed to deer-head height. Boar also likely keep seeds from germinating and seedlings from thriving. Extant populations appear static, waiting for relief from browsing and boar, and I feel these are serious threats given the narrow geographic range of the species.

Sometime along the trip we all remarked that we were simply taking the same photos at each site, as there is some, but not much, floral variation among the plants and populations. We were able to find flowers in pure orange, pure red, and tinted pink, but by and large most plants had the classic orange-red flowers. There was also little variability in size and shape—most plants were quite large and spreading, maybe 10-15 feet in height and somewhat narrower. This raises questions of genetic diversity: How genetically distinct are the populations? And from a botanical garden collection point of view, how extensive would a collection need to be to capture the genetic diversity of the species? I wish we had those answers as we explored each site.

After visiting ten populations over the week, our last stop was Callaway Gardens, whose logo proudly displays the flower of the plumleaf azalea. Having started our trip at Providence Canyon, the most famous wild site for the species, we ended in a famous garden collection where extensive plantings of the plumleaf azalea serve as a template for what we could accomplish at Holden Forests and Gardens. The following day, we returned to our respective institutions after a week in the woods. I had a new anklet of chigger bites, had lost many pounds in sweat alone, but ultimately felt fulfilled—and ready to formulate a plan to return for seeds.

Connor Ryan is the manager of the Rhododendron collections at Holden Forests and Gardens in Kirtland, Ohio.