I’d like to begin by asking you to imagine what the history of your country might have been had it not been a nation but a forest state. Would it have been a democracy, a republic, a monarchy? More than a hundred years ago, writers and thinkers in colonial Bengal were imagining a forest state.

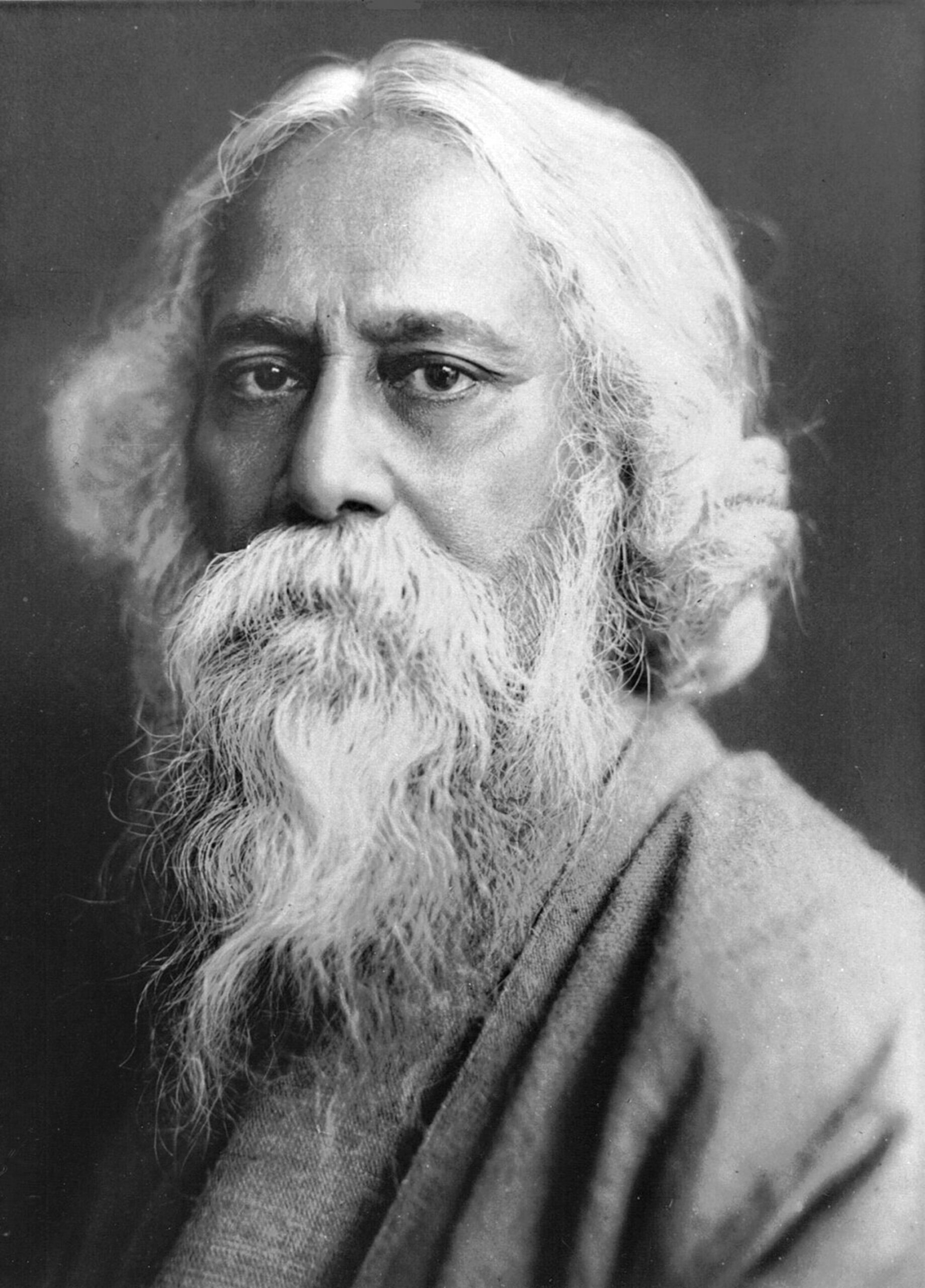

Rabindranath Tagore’s understanding of his own culture—and indeed of his own consciousness—was mediated through a belief in the Indian subcontinent as being a “vast land of forests,” or even a large forest. It might have come to him from having been raised on an Upanishadic way of thinking, it might have also seeped into him and others from literature, both classical and colloquial. Here, for instance, is Bana Bhatta, his name bana meaning forest, in Kadambari: “The forest seems at times and at places to flaunt the trappings of a sovereign state as it were, as its herds of deer wave their chamaras or bushy tails, and bands of wild elephants circle around, the one an insignia of royal power and the other an arm of the defence force.” And here is Rabindranath (in Bengal, we refer to our writers and artists by their first names, not necessarily their surnames): “When the first Aryan invaders appeared in India it was a vast land of forests …

These forests afforded them shelter from the fierce heat of the sun and the ravages of tropical storms, pastures for cattle, fuel for sacrificial fire, and materials for building cottages. And the different Aryan clans with their patriarchal heads settled in the different forest tracts which had some special advantage of natural protection, and food and water in plenty. Thus in India it was in the forests that our civilization had its birth, and it took a distinct character from this origin and environment.

The passage is from Sadhana: The Realisation of Life, published in 1913, the year in which Rabindranath became the first Asian to be awarded the Nobel Prize.

What does it imply, when one sees an entire civilization as having originated in a forest? What makes it different from a civilization that, for instance, is biblically said to have found its birth in a garden, as the civilizational culture of India’s colonizer had? Or one that derives from the sea, which Rabindranath posits as the origin of European culture:

The history of the Northmen of Europe is resonant with the music of the sea. That sea is not merely topographical in its significance, but represents certain ideals of life which still guide the history and inspire the creations of that race. In the sea, nature presented herself to those men in her aspect of a danger, a barrier which seemed to be at constant war with the land and its children. The sea was the challenge of untamed nature to the indomitable human soul. And man did not flinch; he fought and won, and the spirit of fight continued in him. This fight he still maintains; it is the fight against disease and poverty, tyranny of matter and of man. This refers to a people who live by the sea, and ride on it as on a wild, champing horse, catching it by its mane and making it render service from shore to shore. They find delight in turning by force the antagonism of circumstances into obedience. Truth appears to them in her aspect of dualism, the perpetual conflict of good and evil, which has no reconciliation, which can only end in victory or defeat.

India’s culture of leisure, of rest, of optimism, of a natural cosmopolitanism that comes from the accommodativeness of the forest, where there is room for everyone, where no one is rejected, and of ananda, a spirit of joy, pleasure, happiness, contentment, and life-lovingness that Rabindranath understands as genetic to this place and its people, is a gift of forest living.

(I)n the level tracts of Northern India men found no barrier between their lives and the grand life that permeates the universe. The forest entered into a close relationship with their work and leisure, with their daily necessities and contemplations. They could not think of other surroundings as separate or inimical. So the view of the truth, which these men found, did not make manifest the difference, but rather the unity of all things. They uttered their faith in these words: Yadidam kinch sarvam prana ejati nihsratam (All that is vibrates with life, having come out from life).

This understanding of life, which Rabindranath imports naturally from Upanishadic texts, is a challenge to the European post-Renaissance anthropocentric understanding of life—man is not at the center; he is, like all other forms of the living, only a manifestation of life, he is merely one of many, none of whom are rejected by the structure of the forest, and, by metaphorical implication, by the political state.

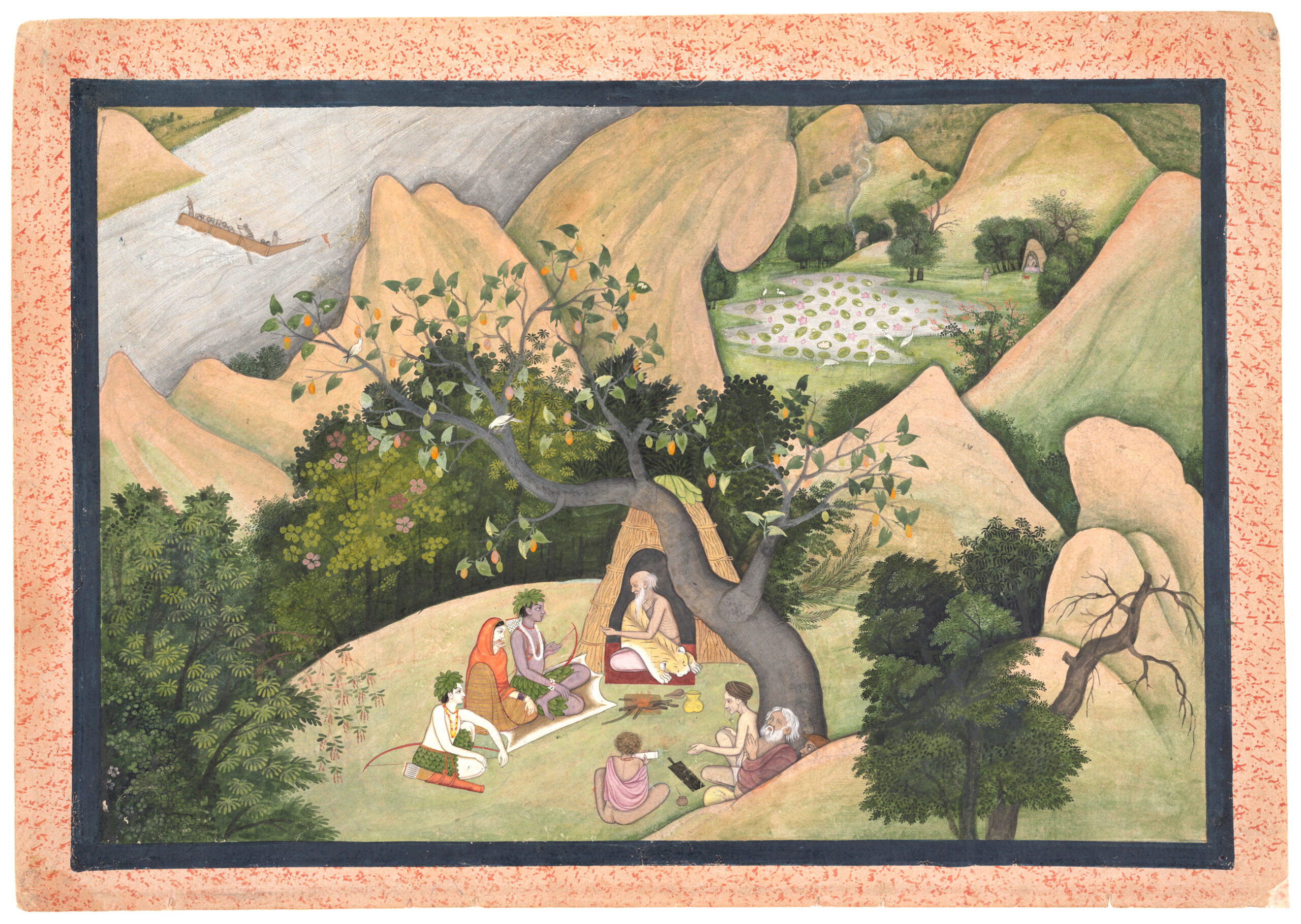

We are given an unexpected interpretation of a model of monarchy, where the king must find their way through a forest—it is a political model based as much on absorption as on renunciation, rule, and vanwas, exile in the forest. Rabindranath chooses to read the Ramayana as the human’s relationship with the forest, with nature, of interest and curiosity and coexistence:

In the Ramayana, Rama and his companions, in their banishment, had to traverse forest after forest; they had to live in leaf-thatched huts, to sleep on the bare ground. But as their hearts felt their kinship with woodland, hill, and stream, they were not in exile amidst these. Poets, brought up in an atmosphere of different ideals, would have taken this opportunity of depicting in dismal colours the hardship of the forest-life in order to bring out the martyrdom of Ramachandra with all the emphasis of a strong contrast. But, in the Ramayana, we are led to realise the greatness of the hero, not in a fierce struggle with Nature, but in sympathy with it. Sita, the daughter-in-law of a great kingly house, goes along the forest paths.

The worship of Ram, the hero, and of his heroism, which has driven India in the last few decades—the Bharatiya Janata Party owes its ascension to its promise of building the Ram Mandir, a temple to Rama, in Ayodhya where the Babri Masjid mosque once stood; “Jai Shree Ram,” Glory to Lord Rama, has changed from an informal Hindu greeting in parts of India to a battle cry during lynching. The overwhelming human-centeredness in this reading of the first epic of the Indian subcontinent is rejected by Rabindranath in favor of a model of forest living that gives dignity to all its residents. Sita, we are reminded, asks questions about all the unfamiliar species she meets in the forest. Only such a life will bring sachhidananda, pure consciousness, pure bliss, says the poet. India’s pilgrimage sites, he notices, are in forested hills, where “man is free, not to look upon Nature as a source of supply of his necessities, but to realise his soul beyond himself.” This is Rabindranath’s plant philosophy, and that is how he imagined India—not the nation state, not the garden, where man is king and controller, but the forest and its natural cosmopolitanism; and it was this that he would try to recreate in Santiniketan, the university town and cultural center founded by the Tagore family in the nineteenth century, and especially in the gardens of Uttarayan there, with his son Rathindranath, carrying seeds, grafts, and saplings from his travels to give them a home irrespective of their nationality, and also in nearby Sriniketan.

Rabindranath was not alone. A few decades before Indian independence, some of its writers and artists were imagining India as a state that derived its political structures from the plant world. Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay was one of them. A college graduate, without a job or parental and financial support, Bibhutibhushan had to leave Calcutta for Bihar to become an assistant manager in an agricultural estate. Diary records of his time there, of clearing the forest to make way for an agricultural estate for his employer, would transform into his novel Aranyak. Rimli Bhattacharya, the translator of Aranyak, notes that the burning of Khandava forest by Arjuna and Krishna is “a necessary prelude” to the events of the Mahabharata, with the forest “consumed by fire to provide a clearing for Indraprastha whose urbane magnificence is only the site of further dissension.” It is a model that has been replicated everywhere— the burning of forests to raise cities, an idea of the urban that refuses to see the forest as a city in its own right. For Bibhutibhushan, the human’s residency in the forest would seem natural, coming, as it would have, from being conditioned to the reasoning of our epics—both the idea of vanwas, exile, and vanaprastha, retirement from the worldly life. The forest compels Satya, the protagonist of Aranyak, to question the idea of who or what constitutes the category of the civilized: “It seemed to me that people in Bengal had become much too civilized in comparison.” And so Calcutta, the only city Satya has seen, becomes an approximation of a nation state, for the idea of the nation is foreign in non-urban spaces in Bibhutibhushan’s literary world.

Both Rabindranath and Bibhutibhushan are turning to the forest as a political model, a thought system that compels the human to see connectedness over individual benefit. Through Aranyak’s protagonist, Satya, whose name means “Truth” (a common name in India), we are given a sense of history of the kind that does not come to us through textbooks:

The forest and hills had been thus for many centuries. So must this forest have been when the Aryans had crossed the Khyber long ago and had entered the land of the five rivers; when Buddha had silently left his home at night … on that night, long ago, the mountain peaks must have laughed as they do on this moonlit night…. And so it was, when the poet Valmiki, immersed in composing his epic Ramayana in his hut by the Tamasa river must have started to find that the day was gone.… Who had inhabited these forests in those distant times? Not too far away from the jungle, I had … seen an old woman who could have been anything between eighty to ninety years old … the absolute embodiment of the poet Bharatchandra’s rendering of Ma Annapurna as an ancient and decrepit woman. Now, I suddenly remembered the old woman—she was a symbol of the civilisation of the forest….

I think of my grandmother, another Annapurna, as I read these passages—the name reveals the relationship with the earth, anna meaning “grain” and purna, fullness; woman as goddess and granary and land. In paragraphs that follow, Satya criticizes the idea of progress, “the Parthenon, the Taj Mahal, the Cologne cathedral … the aeroplane, ship, railway, wireless, electricity,” while “the natives of Papua New Guinea and the ancient aborigines of Australia, and the Mundas, Kols, Nagas, and Kukis of India have not moved on in these five thousand years.”

Satya is induced—inspired—to start planting seeds of wildflowers and plants in the forest even as he gets parts of it cleared. This doubleness seems ingrained in the character of the forest’s fluid cosmopolitanism, so that there can be an ashram inside the forest even as another part is being burnt, where human living is not separate or severed from living with other species, where the word for “hut” and “nest” and “anthill” are the same: basha. Basha is also the suffix in the Bangla word for “love,” bhalobasha, which could also mean bhalo basha or “good home.”

Not only can they hold ashrams; forests also have their own kings and their own political systems. “The leader of the Santal Revolt is still alive,” we are told; “he is the present Raja. His name is Dobru Panna Birbardi. He is very old and very poor, but all the indigenous people of the land give him the respect due to a king. He’s still regarded as a king, although he doesn’t have a kingdom anymore.” It seems like an oxymoron in our world—and in Bibhutibhushan’s, with George V ruling the British Empire at that time—that kings could be poor at all. Raja Dobru Panna’s wealth is his natural nobility and the riches of his memory, of his valor: “These forests and the hills, all the earth, was once our kingdom. I have fought against the Company when I was young. Now I am many years old. We lost our battle. Now there is nothing left.” That they and their politics derive from the forest itself is emphasized in many ways: the king’s grandson “had a body like a young sal tree, muscular and supple”; agriculture, that metaphor of human control over nature, “is forbidden to our race.”

The first page of Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay’s novel Ichhamati, where we see the terrible effects of the Permanent Settlement Act of 1793, begins with a revolutionary formulation of history, where national history is natural history. Both “history” and its Bangla equivalent itihasa are etymologically derived from a shared investment in the human: story or narrative of a person’s life; from asti, meaning “he is.” Bibhutibhushan changes both the subject and the frame:

Take a boat from Morighata or Bajitpur right up to Chanduria ghat, and you shall see the bright red flowers of the poltey and madar trees on either bank, the aquatic foliage of the bonneyburo, the radiance of the yellow flowers of the wild titpalla creeper and the floating leaves of topa-pana; sometimes, along a high bank, you will spy shrubs of uluti-bachda and bainchi in the shadow of ancient banyan and pipal trees, the nesting holes of river-mynahs, and everywhere the pleasing spread of creepers and all manner of greens.… On occasion you may sight a vulture sitting atop one of the crisscrossed branches of a tall silk-cotton tree in a stillness suggesting a higher state of spiritual realisation—like a wash painting done by a Chinese artist.… When the moonlight falls on the green grassy fields that have sprung up on the sandbanks where white clusters of akanda flowers blossom in the summer, and the mild breeze from the river sways the golden laburnum along the banks, travellers journeying along the river will sight the remnants of old ruined homes now covered with a profusion of wild akanda.… As you pass by these ruins of homes you will dream of bygone days, of a mother and her son, of a brother and a sister, whose lives were once entwined with these living signs of habitation. From one century to another many are the unwritten histories of joy and sorrow that lie on their breasts, like the tracery of lines of water in the rains.… Their voices, their stories, are the real history of our nation.

“Real history of our nation.” The history of plant life, records of its settlement on land as well as its death and evacuation from these spaces, a census of plants and trees—all these constitute our national history, not only the life of kings, queens, and the famous. Bibhutibhushan is writing this in a novel published in 1950, the year India becomes a republic and gives to itself its constitution, and decades before the formation of the Subaltern Collective. Seventy-five years later, these words read like a preamble to an imagined India, of what might have been had this understanding of national history been institutionalized. Looking at Gond art in Madhya Pradesh, for instance, with its egalitarian distribution of attention on the natural world, its natural rejection of focus on one species, the species to which the artist belongs, the lines which reveal an interspecies imagination, the use of pigment made from charcoal, mud, leaves, flowers, plant sap, one is tempted to imagine an Indian state like that—the walls of the huts which are the canvas of these paintings, the painters, without formal schooling, so that everyone is allowed the space of creation, this might have been a model for Indian democracy (see Shuchi Saraswat’s discussion of The Night Life of Trees in this issue, pages 57–59).

In the middle of India’s anti-colonial struggle, Bibhutibhushan sees freedom not just as something given to its citizens by the nation state but as a condition of the living, of life. “Freedom” comes from the same root as “friend,” someone or something that is dear. When I think of those I feel closest to, those I love, I notice only one thing common among them— they make me feel free. Why does the nation state not make me feel free? Idiomatic usage, anthropomorphic as it is, connects freedom to birds: the freedom imagined in flight, the supposed lack of obstructions to movement in the sky. Plants and trees, on the other hand, are stuck in the earth, unable to move. To be able to imagine them as free, then, is quite revolutionary. This understanding of freedom, possible to access even when movement is limited, comes from science as much as it does from the Upanishads— plant and planet; all planetary bodies, including the earth from where and from which we seek freedom, kept in their place because of various forces, are free—and, in turn, give us freedom—if we are able to imagine them as such.

The joy of pure freedom, never before tasted, had made their young blood sing. They had been in no state to stop and ask for directions, in no state to stop and consider the consequences of running wildly into the unknown … his sister had realised that she had lost her way. In their glorious run for freedom through the fields, they had seen no villages to mark the way: only paddy fields, marshland and thickets of cane.

This is from Bibhutibhushan’s novel Pather Panchali, on which the filmmaker Satyajit Ray would later base his Apu trilogy. The little boy Apu and his elder sister Durga are running through fields, away from their tiny village where their movements are often limited by their economic class, their poverty. The absence of borders, of things that mark divisions, of “no villages,” of the lack of humans and their habitats on the way, is what enables this sense of freedom. (Two English writers come to mind: John Clare, the form of whose poems and poetic temperament would be deeply affected by the “enclosures” dividing up the English rural landscape of his time— taming the land, its forest and agrarian spaces, into rectangles—and how it would affect his sense of freedom; and D. H. Lawrence, who wanted to imagine a space that had not been touched by the human.) The freedom that Apu and Durga experience is the freedom both of the eye and of the limbs—the eyes meet no obstructions, species of plants keep changing, in a form of visual freedom that is akin to looking at the sky but experiencing it through the body, as one imagines birds doing in flight. It is also the freedom of the unknown, of being unshackled from certainty: to see the imprint of the human hand and the human mind is to feel like a dog on a leash all the time, the reason we never feel free, not even on holidays, for “notifications” of various kinds do not allow us to forget that we are employees, not just of corporations or governments or the nation state, but even when we might be our own employee. “At such times, you should feel no less than the famous explorers who charted new lands.… When I visit one, I ‘discover’ it—with my mind, my heart, and with all of my senses. I taste of its newness, and I am elated” (Pather Panchali). Freedom is looseness, looseness that gives grace—the reason even swaying coconut trees and falling flowers look beautiful to the human eye. This model of freedom that Bibhutibhushan desires comes from the plant world, and it is one that he seeks from the political system.

That is why he shows the damage caused by European colonialism—he calls a few trees “English trees” all through his novel Ichhamati, thereby reminding his readers of how the landscape was being changed by colonial botanists. There is, of course, the indigo plantation, forced on certain areas of Bengal by the British, the cruelty visited both on humans and plants, causing impoverishment to both men and the soil. The introduction of “foreign” trees, seeds, bulbs and cuttings brought by European botanists to Calcutta, its neighboring towns and villages, and to sanatorium towns, began changing the character of plant vegetation as well as the quality of soil. (Richard Axelby, just to cite one example, in his essay “Calcutta Botanic Garden and the colonial re-ordering of the Indian environment,” explains how the botanical garden near Calcutta was changed to accommodate and then give hierarchical importance to migrant plant life.) It isn’t so much the introduction of new species that troubles Bibhutibhushan as the reordering of the natural world and human maneuvering and control over it. Such is the character of India’s plant life, its forests, that even those who are not “Indian,” not born to this land and light, find something in this freedom. The Englishman Colesworthy Grant—“not only a painter, but a poet and a writer as well”—in Ichhamati had found something in this Bengal. “Rural Bengal had opened up new vistas before his eyes … dazzling laburnum trees dotting an unbroken sweep of fields, the clamor of unknown birds from the flowering bushes, shrubs and trees” (emphases mine). How did the Europeans colonize the land? “Luxuriant gardens had once been planted on either side. Huge trees, English trees that Robson Saheb had planted—all of which now made the graveyard heavy with darkness.… Who gave a hoot for it now!” They also colonized a manner of seeing and its concomitant worldview—“spotless and shining,” a phrase used for the English idea of beauty, an utterly human ascription and prescription, is never used for plant life that shares an ancestral relationship with the landscape. “Spotless and shining” is thus turned into an indictment.

Freedom is looseness, looseness that gives grace—the reason even swaying coconut trees and falling flowers look beautiful to the human eye.

To encompass a concept bigger than “India” or any geographical territory, Bibhutibhushan uses the word Bharatvarsha to indicate something more than the concept of “nation” can hold. A world of morethan-human citizenry, a state where the plant and animal and elemental world have equal claims and rights. In Ichhamati, for instance, that word is inaugurated by “the scent of fragrant flowers” and “the green spreading fields of autumn-paddy.”

This is India, Bharatvarsha … Colesworthy Grant mused. He had been wandering all over the country…. The India that he had glimpsed through Monier Williams’s translation of Shakuntalam and in the poetry of Edwin Arnold—for which he had come so far; now at last in all his sojourn he had a sense of a different world, exquisitely beautiful, resonant with poetry—on the banks of a river in this obscure little village in the fading afternoon light. He felt it had been worth all his travelling.

An India imagined through literature, a map, a Bharatvarsha, encountered through experience. Whether the village or the forest in Aranyak, where one of the forest dwellers asks about the location of Bharatvarsha—“Have you heard the name ‘Bharatvarsha’? Bhanmati indicated by shaking her head that she had not heard of it. She had never travelled beyond Chakmakitola. In which direction was Bharatvarsha?”—it seems that Bibhutibhushan is hinting towards a sense of the country being not in its cities. Only in these forest spaces can one feel “the nurturing spirit of the earth, goddess Jagadhatri herself.”

While resistance and disobedience movements against the British by Indians, by the subcontinent’s political thinkers, have been widely studied, it might have been fruitful to think of the many writers and artists who turned to the plant world unconsciously for models outside the hand-me-down European political models such as the nation state. Besides Rabindranath and Bibhutibhushan, there was Kazi Nazrul Islam, for instance, who responded to strained Hindu-Muslim relations and consequent riots with a song such as Mora aeki brintey duti kushum Hindu Mussalman: “we are two buds on the same stem, Hindu and Muslim.” There was Sukumar Ray, arguably Bengal’s finest nonsense poet, who created a poem out the metaphor of the “Biswatoru,” combining Biswa world and toru tree: A “world-tree,” a rejoinder to the narrow confines of the nation state. And there was Jibanananda Das, who tried to imagine a political system in at least two possible ways: by thinking of plants and history, a sense of natural continuity that could exist without human interference; and by turning to grass as a socio-political model. In “Ghash” (“Grass”), a poem from his collection Banalata Sen, grass is turned into something epic, an aesthetic that was usually reserved for “trees”; I’ll paraphrase:

the world is filled with the soft green light of tender lemon leaves; grass like unripe pomelo— a similar fragrance—the deer are tearing it with their teeth! I, too, feel the desire to drink the fragrance of this grass in glassfuls like green wine, I mix and grope this grass’s body—I rub it on my eyes, the wings of grass are my feathers, I am born as grass inside grass, dropping from a dense grass-mother’s dark delicious body.

Grass becomes metaphor—it is the poetic, and it is also his politics, a natural analogy for the human, to humanitas, to humus, to humility, all related to the soil to which grass clings. It is that smell that he seeks—as if by becoming grass he can find secrets of soil and depths that the human body, with its vertical life, has made him forget. “Suranjana,/Today your heart is grass,” he writes in another poem. What does it mean, to have a heart of grass? It is as if life—this world, this world of space and of time, time that he tried to stalk and understand—was composed of grass. Grass, fields of grass, without beginning and end, as infinite as the human heart. It is as if Jibanananda was proposing the rhizome as a counter-model decades before Deleuze and Guattari, the French theorists famous for their talk of the rhizomatic nature of culture and the mind. For Jibanananda seeks to return to earth and its history over and over again, not as tree but as grass.

Seventy-five years after Indian independence, as forests are destroyed and their dwellers turned into refugees, I sometimes imagine what might have happened had the Indian nation state been patient with the thoughts of these plant thinkers of early twentieth century Bengal—what my country could have been, had we modelled our political systems on the ethics of the forest and grass.

Alas.

Sumana Roy is the author of How I Became a Tree (2017), Missing: A Novel (2018), Out of Syllabus: Poems (2019), My Mother’s Lover and Other Stories (2019), and V.I.P.—Very Important Plant (2022). She teaches at Ashoka University. Her poem “The Cherry Blossom on Rüttenscheider Straße” appeared in Arnoldia 80:1 (Spring 2023).