Dan Crowley explores the ancient yews of Herefordshire, whose hollows have seen friends, fire, and the long expanse of time.

Though my home county of Gloucestershire is rightly renowned for its exceptional trees, I often head a little further west to Herefordshire, hotbed of ancient trees, in search of new (to me!) and exciting arborescent treasures. Having read about the Linton Yew—a churchyard specimen once estimated to be an incredible four thousand years old—I decided it was a tree I couldn’t not meet.

En route to Linton I had made a pilgrimage to a favorite tree, another famous yew at Much Marcle. This tree, likewise an ancient (and hollow) churchyard yew (Taxus baccata), has the unusual distinction of having a bench inside it. I gather that it makes for a popular spot for wedding photos for couples who have just tied the knot in the church, though the tree long pre-dates the church by which it stands.

The sun was out when I arrived at Linton—a welcome sight and a break from the near-incessant rain of the previous few weeks. The church stands more or less at the center of its tiny village (aside from the church and a pub, there isn’t a whole lot more there), both church and churchyard sitting at a somewhat elevated position, with a handful of steps leading up from the roadside to the entrance of the churchyard.

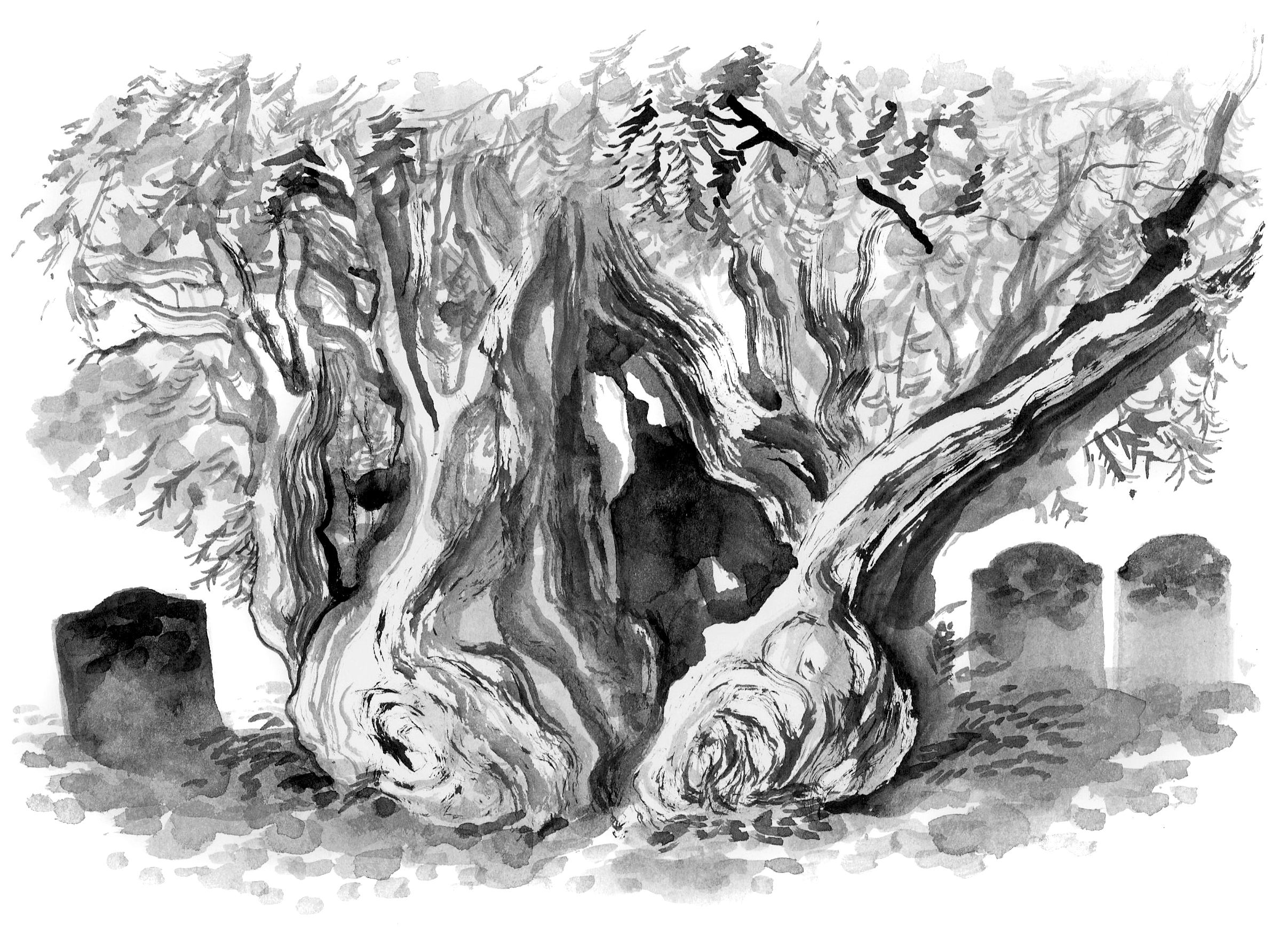

As I walked up the steps, the scale of the Linton Yew quickly became apparent, its dark crown dominating a large part of the churchyard, obscuring much of the church itself. Though its trunk is not quite entire, it is massive, with a prominent bulge less than a meter off the ground. I had read that it had been previously measured at nearly ten meters (!) in circumference. A semi-circle of evenly spaced, painted stones follow the shape of the tree’s trunk part way across the path, acting as a buffer between path and tree.

Coming up alongside the tree, I could see a huge V-shaped opening facing the path, revealing the large extent to which the trunk is hollow. Like the Much Marcle yew, it would be quite easy to step right inside the tree’s hollow bole—though here that sort of action is evidently viewed as an intrusion. Accompanying the painted stones is a sign, printed on laminated paper and pinned to a wooden stake propped against the tree, the base of which extends through a hole in the stem. It reads “KEEP OUT… Please help protect this ancient tree by not entering its hollow trunk,” and includes a note that the tree is “lovingly maintained” by a local arboricultural company.

Hollow trunks and an ability to continually regenerate make yew trees notoriously difficult to age.

I then noticed what is presumably the primary reason that the sign and stones have been put in place: much of the inside of the trunk was charred, with large, blackened areas evident on all sides. Clearly the tree had been the victim of a significant fire at some point in its not-too-distant past.

Moving around the tree, I could see that on its southern side, closest to the church, a wooden prop had been installed, put in place to bear the weight of branches overhanging the path around the church. I also noticed the odd fruit: evidence that the Linton Yew is female. Inside the original trunk of the tree grows a “new” stem a foot or so in diameter. Seemingly derived from an adventitious root, it makes for a fine exhibit of why yews are so apt to regenerate.

Finding myself almost at the entrance to the church, I wandered into the porch, pondering that there might be some information on the tree there. Scanning the noticeboard, I saw—alongside the listing of the altar-flower rota and calendar of services—a two-page piece on the tree, including black and white images of the tree “today” and in 1909, though details in the latter were hard to make out. According to the church’s information, the age estimate of four thousand years was printed on a certificate awarded to the church by the Conservation Foundation, an age that would make the tree the oldest yew in England. However, recent estimates are more conservative at around 1,500 years old, though its giant girth renders the Linton Yew the largest yew by circumference in the country, and the UK Tree Register and Ancient Yew Group both believe it could be the oldest as well. Hollow trunks and an ability to continually regenerate make yew trees notoriously difficult to age! The article did state with certainty when the tree was set on fire, though—nearly catastrophically, in 1998.

Though only a single tree goes by the name of the Linton Yew, it is not the only yew in Linton churchyard. Experience has taught me that where there is one good tree, there’s often another (or more). And churchyards often tend to throw up one or two surprises.

With that in mind, I made my way around the church building, passing a few specimens of Irish yew (Taxus baccata ‘Fastigiata’), before being faced with another impressive specimen! Though not of the same dimensions as the tree out front, it was definitely ancient, with another largely hollow trunk supporting a good, rounded crown. It too was entirely open on one side, the gap proportionately narrower. I wondered if this tree was an offspring of the Linton Yew. Surely feasible, but what struck me most about this specimen was its bark, which was far more textured than that of its presumed parent, exfoliating in small flakes.

As I stood by the second Linton yew, a maintenance contractor came around from the front of the church to tend a grave to the east of the churchyard. I continued to marvel at this taxaceous beauty a while longer, though when he fired up the strimmer to cut some grass, I decided it was time to leave. I wandered back around the front of the church the way I came and out down the path, pausing briefly once more at the Linton Yew before heading on my way, as the skies clouded over once again.

Dan Crowley is a dendrologist and is tree conservation manager at Westonbirt, The National Arboretum, UK. As well as his role at Westonbirt, he enjoys documenting trees in the UK and beyond. He posts on Instagram @thetreespotter.