Daniel Faccini revisits the botanical wonders of the Canary Islands, pursuing the story of their evolution—and reflecting on their endangered beauty.

Years before the Origin of Species, the barnacles, the stories about moths and orchids, and even before stepping into the Beagle to sail around the globe, the young Charles Darwin could only dream about the natural wonders of the tropical world. Of his dream travels, the first one, an island near the west coast of Africa, would come from the pages of Alexander von Humboldt’s diaries. “All the while I am writing now my head is running about the Tropics: in the morning I go and gaze the Palm trees in the hot-house and come home and read Humboldt: my enthusiasm is so great I cannot hardly sit on my chair … I never will be easy till I see the peak of Teneriffe and the great Dragon tree; sandy, dazzling plains, and gloomy forest are alternately uppermost in my mind.” He would never get to the islands, however. The year he wrote this passage, he missed the boat bound for the Canaries. Years later, while aboard the Beagle, he could only glimpse from a distance how the peak of Mount Teide rose above the clouds of Tenerife, as a quarantine denied him the chance to set foot in his dreamland. “I must have another gaze at this long wished object for my ambition.—Oh misery, misery.… We have left perhaps one of the most interesting places in the world, just at the moment we were near enough for every object to create, without our utmost curiosity.” What did Darwin miss?

I first saw the peak of Mount Teide on a sunny afternoon in the last days of May. As my plane flew around Tenerife, a dark, enigmatic volcano rose above the clouds through my window, a colossal presence that marked the beginning of the first field season of my Ph.D. work. It appeared as two islands in one, one emerging from the Atlantic and the other rising from a white ocean of clouds. Far from being a uniform landscape, a geography of dramatic fractures and ridges spanning a vertical gradient of more than ten thousand feet conveyed the feeling of a vast corrugated continent rather than a small and remote island. Just outside the airport, the plants I had been reading about for months started leaning out from the nearby gorges. Dandelion trees, woody daisies, and the Echium shrubs branching like towering candelabra made a short drive into an hours-long journey.

Every time I asked about a species, he would close his eyes as if embarking on a mental journey across the island.

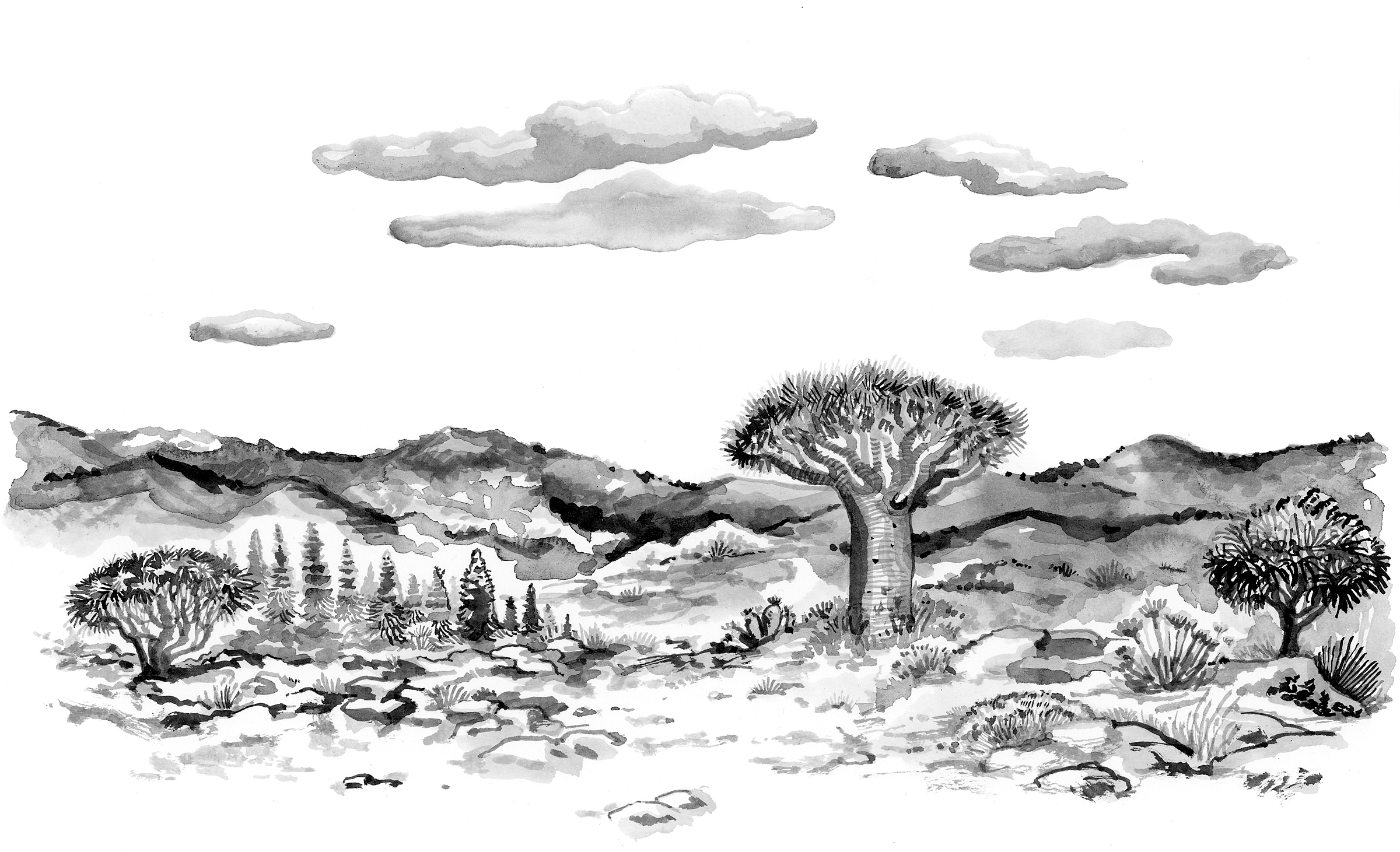

I was there to find answers to a question that Darwin himself outlined: why is it that all around the world, small, herblike continental plants evolve into Seussian-looking shrubs and trees when they colonize islands? It was the well-studied yet unapprehended Echium or dragon tree that brought me to the archipelago, and it was through its diversity of forms and insights from decades of past research that I hoped to unravel the puzzle. Surrounded by these plants as I drove around the island, my perplexity only grew. Of these memorable encounters, the most mythical came when I stumbled upon a dragon tree as the sun was about to set. Its heavy trunk stretched to the sky, forming an umbrella of bifurcating branches, and its glossy bark—closer to the scaly skin of a reptile than that of a plant—was topped with long green leaves as pointy as spears. Yet if the tree ever awakened as a dragon, I thought, it would probably be a gentle, slow-moving beast. I spent the night in La Orotava. The next day, I would meet the director of the local botanical garden, the great Canarian botanist Alfredo Reyes.

When I entered La Orotava Botanic Garden, I felt transported to the time I lived in the buzzing dry forest of the Colombian Caribbean. The garden had once been a mandatory stop during European explorations, where most tropical American plants were grown before continuing their journey to the greenhouses in continental Europe. The collection was full of plant species that, for some time, had only been growing in my memory. I greeted these relatives of my old companions and followed Alfredo to his office. A tall man, he navigates delicately through space, pauses briefly before answering a question, and often points out something in the surrounding vegetation. His office was that of an old-school botanist: newspapers with rare plants everywhere, curious fruits and seeds standing in wooden cabinets packed with floras, and botanical plates and engravings hanging on the walls. I met his colleague and former student, Miguel Padrón, and discussed Echium and the expedition. Every time I asked about a species, he would close his eyes as if embarking on a mental journey across the island before sharing the names of one of the many barrancos (gorges) or even some coordinates. “You can find that plant there,” he said. I smiled. During the first few days, I would be on my own, with Alfredo and Miguel set to join me later in the week. I looked at my notes in the field notebook: a list of names of places I could barely imagine. I left his office. I had no doubt which plant was the first one in my quest.

I drove through the dry vegetation near Puerto La Cruz, then went up to La Orotava town and took the road to Las Cañadas del Teide. The greenery that at first was closer to tanned yellow rapidly transformed into a dark green, and the short shrubs turned into trees. I noticed how the car windows collected drips of water until I was surrounded by fog and could barely see the heather trees and the fayas (Myrica faya). Only the gleaming red trunks of the madroño canario (Arbutus canariensis) struck like flashes of lightning in the humid veil that had enclosed me. I followed the narrow road as it ascended further into the mountain, soon finding myself immersed in a Canarian pine tree forest. This distinct forest was brown in color. Trunks and dead pine needles framed a sparse understory with a fresh scent. In less than an hour, I had traversed three completely different ecosystems, the boundaries between them so clear that I felt like I was traveling between islands and not within the confines of a single one.

I soon left the pines behind, and the fog opened to a desolate horizon of volcanic rock with some sparse green spots and white broom flowers that inundated the air with a delicate-sweet smell. And there it stood! A giant rosette of silver and furry leaves erupted in a single eight-foot-tall column of ruby-colored flowers: Echium wildpretii, the iconic tajinaste del Teide, in full bloom. My delight persisted. Once you see a plant, you cannot unsee it. You engage in a relationship with it as it becomes ingrained in your imagination, and you start recognizing it wherever it grows as if a new layer of the world has come afloat. Even if you forget the name, you will always acknowledge how it looks—its overall impression, what Goethe called the Gestalt. Along with a botanical press, seed bags, and my red pruners, it is the Gestalt of the plants I have known in the past that I carry most dearly to the field. This is how I navigate the world to find them.

Alfredo and Miguel guided me on my last day in Tenerife. We drove to the island’s northern gorges through a dense and humid laurel forest with trees covered by a mossy layer and a fern understory that reminded me of Darwin’s dreams. The forest rapidly yielded to a drier, Mediterranean-like shrub ecosystem. We parked and started hiking. We walked until we reached a northern-facing slope, the only place where the arrebol tajinaste (Echium simplex) grows in the wild. We sat on the edge of a cave shaped by millions of years of erosion. In front of us, the land suddenly sank a few hundred feet into the blue Atlantic. Alfredo and Miguel started showing me the endemic species growing there and the count quickly went up to thirty. In that piece of land, small enough that we worried about making a misstep and falling to our deaths, thirty plant species that grow nowhere else in the world happily bloomed. I could almost see the evolutionary tree branches sprouting here and there! This evolutionary exuberance is what Darwin missed, I thought. An island where so many perplexing evolutionary stories of plants unfold before our eyes—a place rightfully called “The Galápagos of Botany.”

Along with a botanical press, seed bags, and my red pruners, it is the Gestalt of the plants I have known in the past that I carry most dearly to the field.

Yet, this is an endangered beauty. We live in the time of now-or-never for our biological studies on the islands. Every species extinction is an irreplaceable loss of information, one lost word in the history of life on Earth. The Canary Islands hold many cues to understand how small-herbaceous plant lineages evolve into tall trees and shrubs and how the stunning diversity of plant growth forms has come to be. But most endemic species are in great peril and, with them, the depth of our understanding of life. As I write this, a wildfire that has burned over twenty thousand acres on Mount Teide still rages. Many trails I walked earlier this summer, collecting mesmerizing plant species, have vanished amid ashes and smoke. How many plants have been lost to the flames? Enough to think that if we fail to do something about it, not only Darwin, but the generations to come will miss the unique organisms that inhabited these islands long before we did.

Daniel Faccini is a Colombian botanist and doctoral student in Ned Friedman’s Plant Morphology Lab at Harvard University.