Christina Varnava learns that it takes persistence, directness, and optimism to communicate sustainability in a land of abundance.

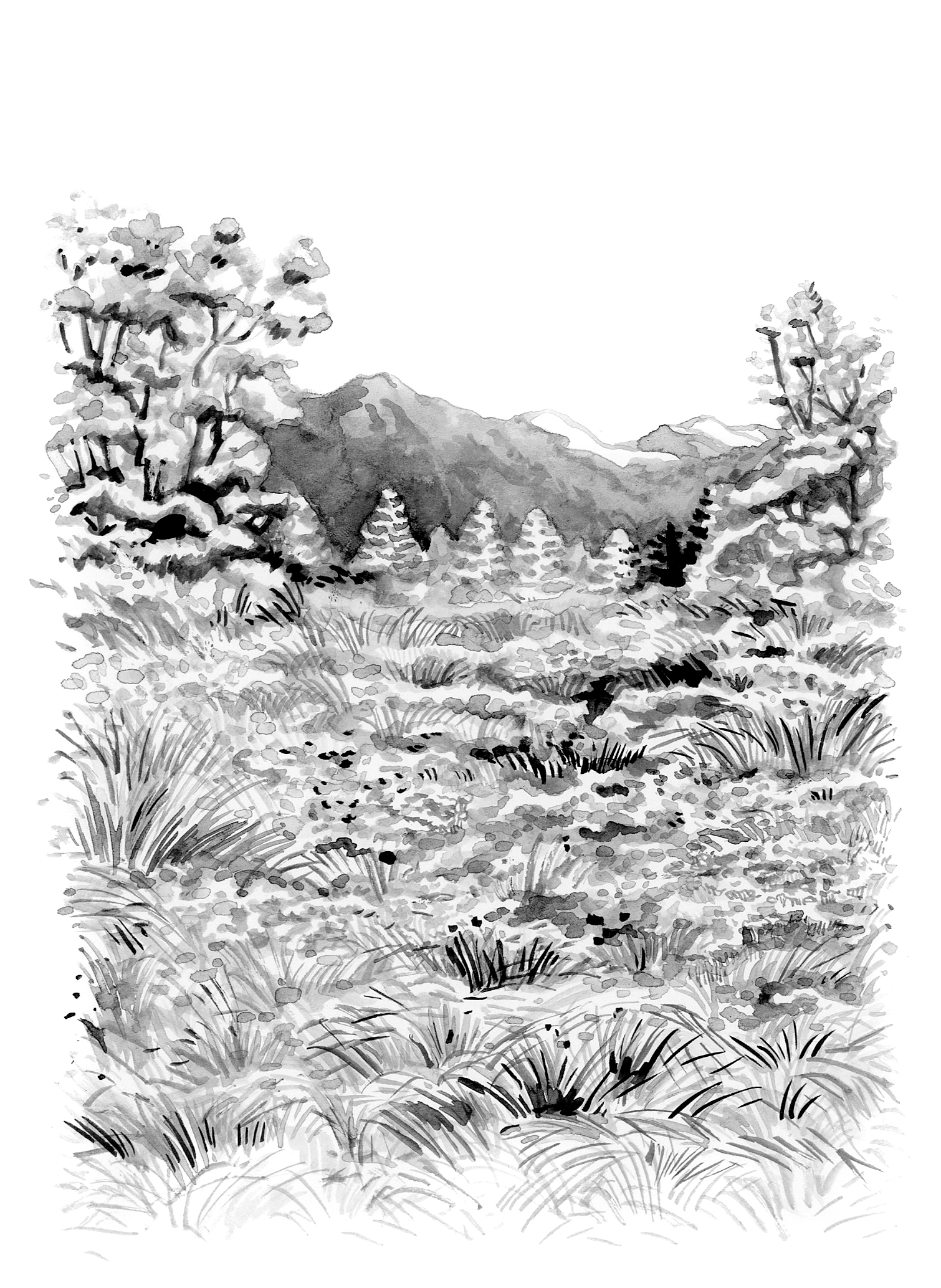

I was walking through our collections at Santa Barbara Botanic Gardens one day in early December—it was 68 degrees, a sunny day. One of our gardeners flagged me down accompanied by a visitor who had a question about our meadow, which is filled with native grasses and forbs. In springtime the meadow is an explosion of California poppies (Eschscholzia californica), but in the heat of a dry December, it’s mostly dominated by purple needlegrass (Stipa speciosa).

The visitor—a hip-looking woman with dyed magenta hair and fashionable sunglasses—got straight to the point. She wanted to know why our meadow looked so dull. She asked why we didn’t just add more flowers to keep it blooming all year. It’s not an uncommon question—folks here in southern California are used to seeing the year-round abundance of tropical ornamental plants. California has been idolized as a land of boundless resources for nearly 200 years. We are beginning to understand the true ramifications of this belief as water tables lower and we buckle under drought conditions and record heat waves. Part of my role as an advocate for native plants and habitats is pushing back against this false narrative. I believe it is vital to educate people about the unusual Mediterranean climate that shapes the plant life here in California: hot, dry summers and cool (hopefully wet) winters. Plants in California experience drought conditions for months at a time, during the hottest months of the year. Most native plants are adapted to this cycle, but the tropical plants and lush lawns we’re used to seeing require additional water to survive.

With all of this knowledge at my command, I felt well-equipped to answer this pointed question from our visitor. I replied that most California native plants are dormant this time of year, especially the showy annuals. I explained that we were currently in the dry season, and that while most plants were waiting for rain, other plants in the garden were having their moment.

This visitor, however, was persistent, and she was not satisfied with my answer. She responded that it was a shame to waste such a great space with abundant sun on such a drab display. It’s hard to blame her for thinking this way, when gardeners in southern California have long celebrated the ability to plant anything and everything. Our mild winters allow for ornamental plants from around the world to be cultivated here—they just need plenty of water to get through the summer. For an example close to home: massive ornamental banana plants, roses, ivy, cacti, bluegrass, boxwood, yucca, and star pine all grow in the courtyard of my apartment complex—where the sprinklers run every night. And that’s the key point. This apparent abundance comes at a cost, and we don’t, in fact, have unlimited resources. California has declared a drought-related state of emergency twice this century, during the drought from 2007–2009 and again from 2012–2016. No one is certain how the changing climate will impact the drought cycles in the southwest, but it seems prudent to prepare for further droughts.

To our visitor I explained that for plants in California, late fall is the equivalent of winter for plants in other parts of the country. Plants here struggle the most during this time of the year, when they have been waiting for water all summer. Our spectacular superblooms are built on this cycle of drought and rain, and they are not something that plants can support year-round. Ultimately, water is the limiting factor for them, and for us. We also try to garden sustainably and use minimal water. The fact that the meadow is located in a warm, sunny area provides difficulties for the plants in its own way. While it stands in opposition to how most people are used to thinking about plant stress, it is part of our unique climate.

Our guest countered my statement, noting that we had gotten a lot of rain since last year. The lakes and reservoirs were all full again, so shouldn’t a lack of water no longer be a problem? I tried to explain that one rainy winter was not enough for the long term, that our groundwater was still depleted, that we still desperately need to see water as a precious resource.

She shook her head, and pointed out that if the cut-flower fields in Lompoc could do it, so could we. She ultimately did not seem swayed by anything I said, and she walked away shortly after. I keep thinking about how we are trying to turn back the clock on a very old narrative. We are trying to combat the anthropogenic view that the world is full of resources to extract for humanity’s benefit, and it will not be easy to change this attitude.

I struggled after this interaction to think of anything else I could have said to be more compelling, or more persuasive. Day to day, I usually interact with people who understand my passion and my commitment to protecting California’s wild plants and places. This interaction was an important reminder that there are still many people who think of water as just another resource for humans to use. Many don’t yet understand the value of water simply accumulating in the ground, but I hope that someday they will. That’s why I keep practicing scientific communication. That’s why I keep writing, reading, and advocating. That’s why I keep adding plants to our collection, and why I keep sharing their stories. We can’t just get through to the people that already buy in. So, I am prepared to stay put through the difficult conversations and face each one with optimism.

Christina Varnava is the Living Collections Curator at Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, where she manages nearly a century of plant records. She loves the plants and wild landscapes of California.