One winter night a few years ago I was woken by the wind, and, unable to fall back asleep, I decided to walk around my apartment, to still those thoughts that intensified the longer I laid in bed. I walked around my small apartment, I paced really, when suddenly, I came upon the silhouette of a tree. It was a shadow, cast by a neighbor’s tripped floodlight, this much I could intuit even in my half-awake state; but these elements—wind, tree, floodlight—had never before found each other in this particular arrangement. The shadow-tree and I faced each other. It was immense. Its limbs and trunk extended all the way to the edges of the coat closet door, as if it knew it was in frame. Likely it was a Norway maple (Acer platanoides)—common enough in my Boston neighborhood as to have become nearly invisible—but isolated and in shadow it had become mysterious, its upper twigs ghostly and faint, swerving, intersecting, flickering; moving. Our encounter lasted only a few minutes, but I haven’t forgotten it—in part because the shadow-tree hasn’t appeared again since. It was there, then gone.

Our ability to see diminishes in the dark. The air texturizes, a grainy film that muddies colors, disappears objects. What we see best are the edges of things, and our mind fills in the rest, pulling from experience, supposing, guessing. With the loss of one sense comes the sharpening of other senses, and sometimes, a retreat into the caverns of the mind, where fear grows, but imagination too. How many fairy tales, fables, and myths there are of people lost in the forest, within the land of the trees, afraid of the encroaching night, sealed, impenetrable, from which the only relief are thoughts of escape, moonlight. Light. The less you can see, the stories seem to say, then the more danger you are in.

The Gond tribe, indigenous to the forests of central India, have several such stories. In one, a cowherder and a young calf enter the woods during July’s monsoons, in search of the calf’s mother. Cloudy skies, a dense, wet forest; soon, cowherder and calf are lost, in despair. A firefly watches and decides to help. She guides the pair to a Sembar tree, alight with more fireflies. Under it, the lost cow waits.

This fable is part of The Night Life of Trees (Tara Books, 2006), an art book that takes the form of a children’s picture book, pairing Gond folklore with paintings by one of three prominent Gond artists silkscreened on thick, black paper. Ram Singh Urveti visualizes the Sembar as a bright green apparition with a skin made of tight, oval scales, saffron colored beams—the fireflies—flaring from the branches’ partings. The tree floats in the center of the page, borne from it, fabulously unrooted; the Sembar does not recede as the night arrives, but becomes more alive.

The fable comes with the expected lesson—this one being that if you are lost in the woods, then look for a firefly or a Sembar and you might be saved. My Western-educated mind intervenes: what kind of tree is a Sembar? Mostly likely Bombax ceiba, but the painting offers no confirmation. Urveti and the two other artists contributing to the book—Bhajju Shyam and Durga Bai—are mostly concerned with expressing their ancestral connection to the natural world.

The Gonds are one of the largest of the tribal groups living in India. The artists belong to the Pardhan Gond clan, historically the bards and singers, carriers of their communities’ stories. Visual art is central to their way of life. For festivals, they use colored mud and organic materials to decorate the walls and floors of their home with geometric designs known as digna. Durga Bai, who paints five of the nineteen illustrations in The Night Life of Trees, began as a digna artist at the age of six. She, like many established Gond artists, considers Jangarh Singh Shyam her mentor. Shyam is noted as one of the first among the Gond to use paper, canvas, and synthetic paints, and to gain international, institutional recognition for his work. Many followed him, leaving the village for Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh’s capital city. In the biographical note to another book Durga Bai illustrated with her husband, Bhimayana: Experiences of Untouchability, Incidents in the Life of Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar (Navayana, 2011), she describes the move: “Jangarh-jija and his wife Nankusia invited many talented artists like us to the city, gave us shelter, and helped us explore the world of contemporary art. They are the deep roots of a large tree. Subhash and I are one of the branches on that tree. We owe everything to them.”

Trees—metaphorical, mystical, useful. In The Night Life of Trees humans turn into trees; deer are mistaken for them. A squirrel dreams of having another body, only to realize there’s nothing better than being a squirrel sitting in a tree. “The Tree of Intoxication” warns that the liquid extracted from the flowers of the Mahua (Madhuca longifolia) may heal ailments, may even be enjoyable to drink, but too much will turn a person into “a mouse or a tiger, a pig or a pigeon.” In that painting—by Durga Bai—the severed heads of the three creatures are stacked within the column of the trunk, maniacally in wait. The Peepal (Ficus religiosa), as illustrated by Bhajju Shyam, is one of the few which retains its autonomy. Illustrated in tidy, long lines, it slopes upward, contained. The accompanying text describes the Peepal as being “so perfect that seen against the sky, it seems to have the same shape as its own leaf. The detail is the same as the whole.”

The last page collects all nineteen paintings in silhouette on a sheet of brown kraft paper. It reminds me of one of those dendrology charts in which the trees are labeled by their shape—pyramidal, round, broad, oval, columnar, weeping. Except here, they are a gathering of shadows, catalogued by artist name. It’s like seeing the paintings in negative; without their intricacy, they appear like dancing figures, returning to the cover of night.

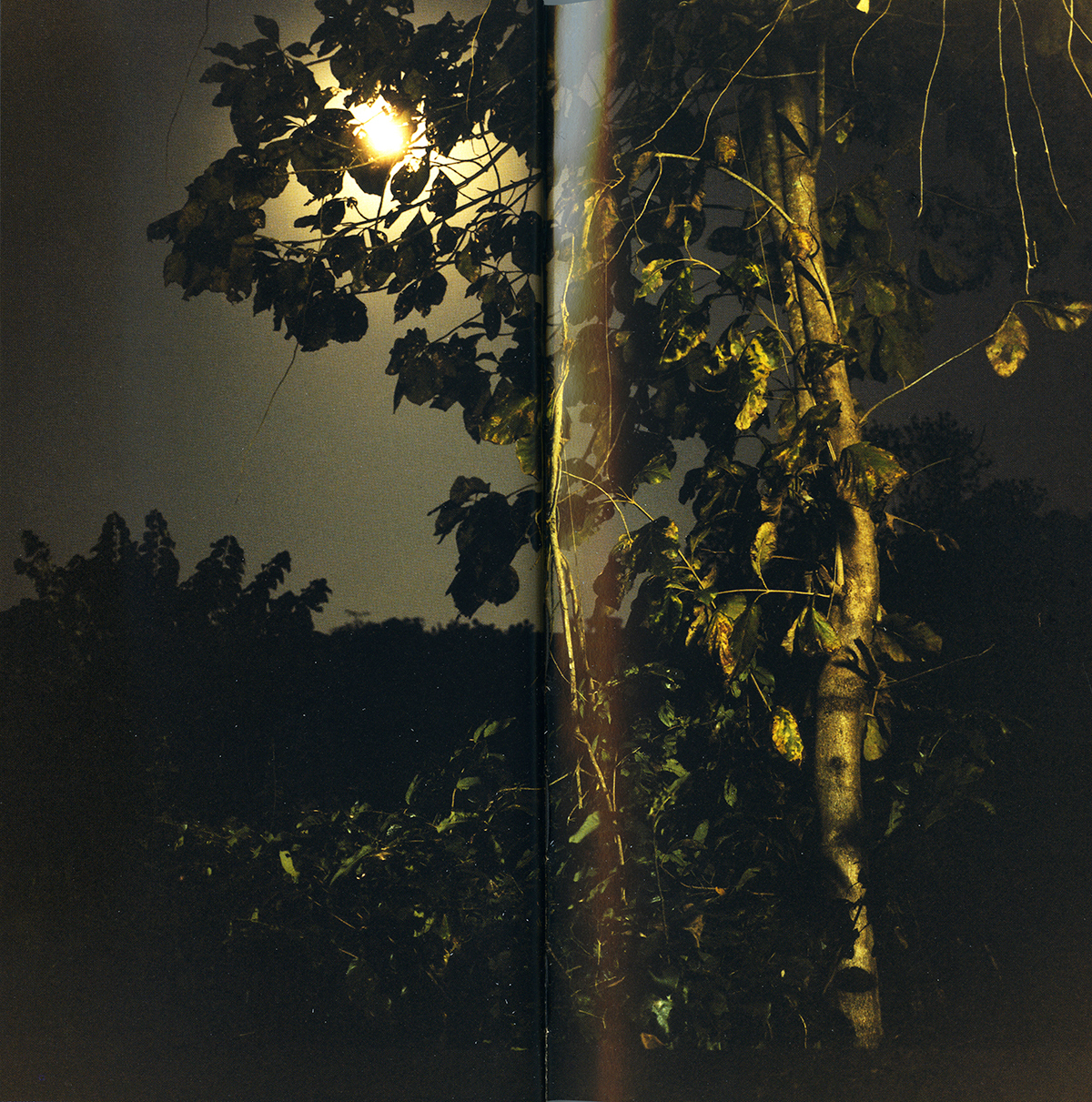

Night arrives in the city. It falls (or does it rise?) and at once it is tempered by the lit squares of windows, streetlights, the twin beams of passing cars. It’s a filled night, crowded still, even as it empties of human activity. “And what greater delight and wonder can there be than to leave the straight lines of personality and deviate into those footpaths that lead beneath brambles and thick tree trunks into the heart of the forest where live those wild beasts, our fellow men?” writes Virginia Woolf in her essay, “Street Haunting.” Delhi-based artist Dayanita Singh evokes this sense of communion in her book of night photography, Dream Villa (Steidl, 2010) a work that I think of as an urban sibling to The Night Life of Trees. Also set against a black sky looming with forms, it speaks in similar, if duskier, reds, greens, blues. Trees are not the subject, but neither is any one being or object; the photographs’ focus appears almost accidental. It’s the light that dominates, its peculiar insistence. All are joined in its artificial glow.

Singh considers her books “photo-novels” yet Dream Villa contains no accompanying text. I think of Woolf’s “straight lines of personality”—our attachment to our self as Self, perhaps? or maybe to narrative, to sense-making?—and the relief in temporarily abandoning verbal language’s responsibilities, the human impulse to create order.

That night I paced, it was, I’m remembering now, the news of the day that kept me awake. Scrolling headlines. I walked to resist picking up my smartphone; once exposed to that blue light, I wouldn’t be able to fall back asleep. After I encountered the shadow-tree, my worries didn’t leave me, not quite. But another image flashed before me—this one of Ramón y Cajal’s drawings of Purkinje cells, the neurons that live in the back part of the human brain. Filigreed, liquidy—dendritic. That we contain cells resembling trees—there is a little comfort, in that.

Shuchi Saraswat is a writer based in Boston.