Fothergilla gardenii, commonly called dwarf fothergilla, is native to the moist coastal plain from North Carolina to Georgia and also the Florida panhandle along the Gulf Coast. The plant typically grows only 2 to 3 feet (.6 to .9 meters) tall and spreads slowly by underground stems, making it an ideal size for smaller landscapes. Although its native range falls within USDA Plant Hardiness Zones 8a to 9a, it can be grown successfully through Zone 5. The Arboretum’s most interesting individual of the species, accession 681-88-A, was originally wild collected near Jesup, Georgia, by Harold Epstein, renowned New York plantsman. The specimen was much smaller than typical F. gardenii—only 12 to 15 inches tall and with proportionately smaller leaves and flowers. A rooted layer of the plant was sent to the Arboretum for evaluation in 1988, and in 2001, as part of our Plant Introduction, Promotion, and Distribution Program, it was released under the cultivar name Fothergilla gardenii ‘Harold Epstein’ (Bennett 2000). The original diminutive plant we received can still be seen in the Arboretum’s Leventritt Shrub and Vine Garden.

Its cousin, F. major, commonly called large fothergilla or mountain witch-alder, grows upland from F. gardenii in the southern Appalachian Mountains from North Carolina and Tennessee to South Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama. A disjunct population is also found in Arkansas. Growing at higher elevations (and therefore in cooler conditions) and in leaner, drier soils, large fothergilla is hardier (to USDA Zone 4) and less finicky than dwarf fothergilla. Large fothergilla can reach upwards of 10 feet (3 meters) in height, forming a large mass over time. The Arboretum’s finest specimen (694- 34-A), accessioned in 1934, was found as a seedling growing at the base of the parent plant in the Arboretum. It was ultimately transplanted to a spot near the main gate along the Arborway, where it thrives today for all to enjoy. The 10- by 10-foot plant is consistently engulfed with blooms in the spring and displays magnificent fall color. Wild-collected representatives of the species can be found in the Leventritt Shrub and Vine Garden and on the summit of Bussey Hill and in the Explorers Garden.

Increasing interest in finding reliable native plants for home landscapes has boosted the popularity of fothergilla in recent years (Darke 2008). Another factor in raising fothergilla’s profile is the recent introduction of new cultivars, particularly those that we now know are the result of hybridization between F. major and F. gardenii. In the Arboretum’s propagation records, the earliest determination of a hybrid between the species is from 1980, made by Richard Weaver, the Arboretum’s horticultural taxonomist and assistant curator at the time. As a graduate student at Duke University, Weaver had helped to settle the long-standing debate over the number of Fothergilla taxa (some authors had cited as many as four) by counting chromosome numbers and comparing morphological features of the species (Weaver 1969). Some of the samples he used for comparisons were from the Arboretum, and in his subsequent years working here Weaver continued his interest in Fothergilla and the rest of Hamamelidaceae (Weaver 1976; Weaver 1981).

The plants noted in 1980 as “Fothergilla hybrid—F. major × F. gardenii” were seedlings from a 1967 accession (709-67) received as open pollinated Fothergilla gardenii seed from the Botanical Gardens of Villa Taranto in northern Italy. Several individuals appeared distinct from the others, leading to the hybrid notation. Later entries (1983) noted that in fact “Dr. Weaver counted chromosomes” to determine that the plants were hybrids between gardenii and major. Although no formal publication of the hybrid was made, Michael Dirr, following a year-long fellowship at the Arnold, notes in the 1983 revision of his Manual of Woody Landscape Plants that “The Arnold Arboretum has identified a hybrid between the two species which offers intermediate size and other characteristics. This could be a most valuable shrub for modern landscapes.” Dirr’s manual, well known for its cultivar descriptions, listed no cultivars for Fothergilla at the time—a testament to the lack of horticultural attention the genus had received (Dirr 1983).

Around the same time, selections of fothergilla noted for improved ornamental traits and adaptability began to enter the nursery trade, most identified as F. gardenii cultivars (Darke 2008). ‘Mt. Airy’, a 1988 Michael Dirr selection from a plant growing in Cincinnati’s Mt. Airy Arboretum, was one of the first named fothergilla cultivars and is still perhaps the best known and most widely planted. The true identity of ‘Mt. Airy’ and other cultivars as either gardenii or major was certainly confusing, and in many cases the species names were used interchangeably in the horticulture industry. Research by Ranney and others (2007) finally determined, through cytometry, that the majority of cultivars available today, including ‘Mt. Airy’, are in fact hybrids between gardenii and major.

The hybrid was officially described and named Fothergilla × intermedia (Ranney et al. 2007). The increasing success of fothergilla in cultivation can be attributed to the hybrid’s adaptability and hardiness—gained from F. major—and the landscape-friendly intermediate size, typically 4 to 5 feet (1.2 to 1.5 meters) tall. Within the Arboretum collections, fine specimens of Fothergilla × intermedia ‘Mt. Airy’ grow in the Leventritt Shrub and Vine Garden (429-2002- B and -D), along with several accessions near the summit of Bussey Hill.

Ancestors from the Persian Empire

Parrotia Jacquemontiana. – This is now flowering for the first time in the arboretum at Kew. It differs from Parrotia Persica in having smaller flowers arranged in a conical head and surrounded by ovate petaloid whitish bracts nearly an inch long. The flowers are developed before the young leaves. When mature, the leaves are orbicular or obovate, distinctly toothed all around the edges, dull green, and they do not assume the bright colors in autumn so characteristic of Persian species. The former is a native of Kashmir at an elevation of from 5,000 to 9,000 feet, where it forms a Hazel-like bush, six to twelve feet high. Dr. Aitchison [Scottish surgeon and botanist known for his plant collecting in India and Afghanistan in the late 1800s] found it in abundance in Afghanistan in the interior of the hills, forming much of the shrub jungle there. He says the long slender stems and pliant branches are used in wicker-work and for the handles of farm implements. As a garden plant it is not as valuable as P. Persica, which at Kew forms a beautiful shrub or small tree, bearing large glossy leaves all summer, which in autumn change to the richest hues of orange, red, brown and yellow.

C. S. Sargent, Garden and Forest: Foreign Correspondence. London Letter. 1896

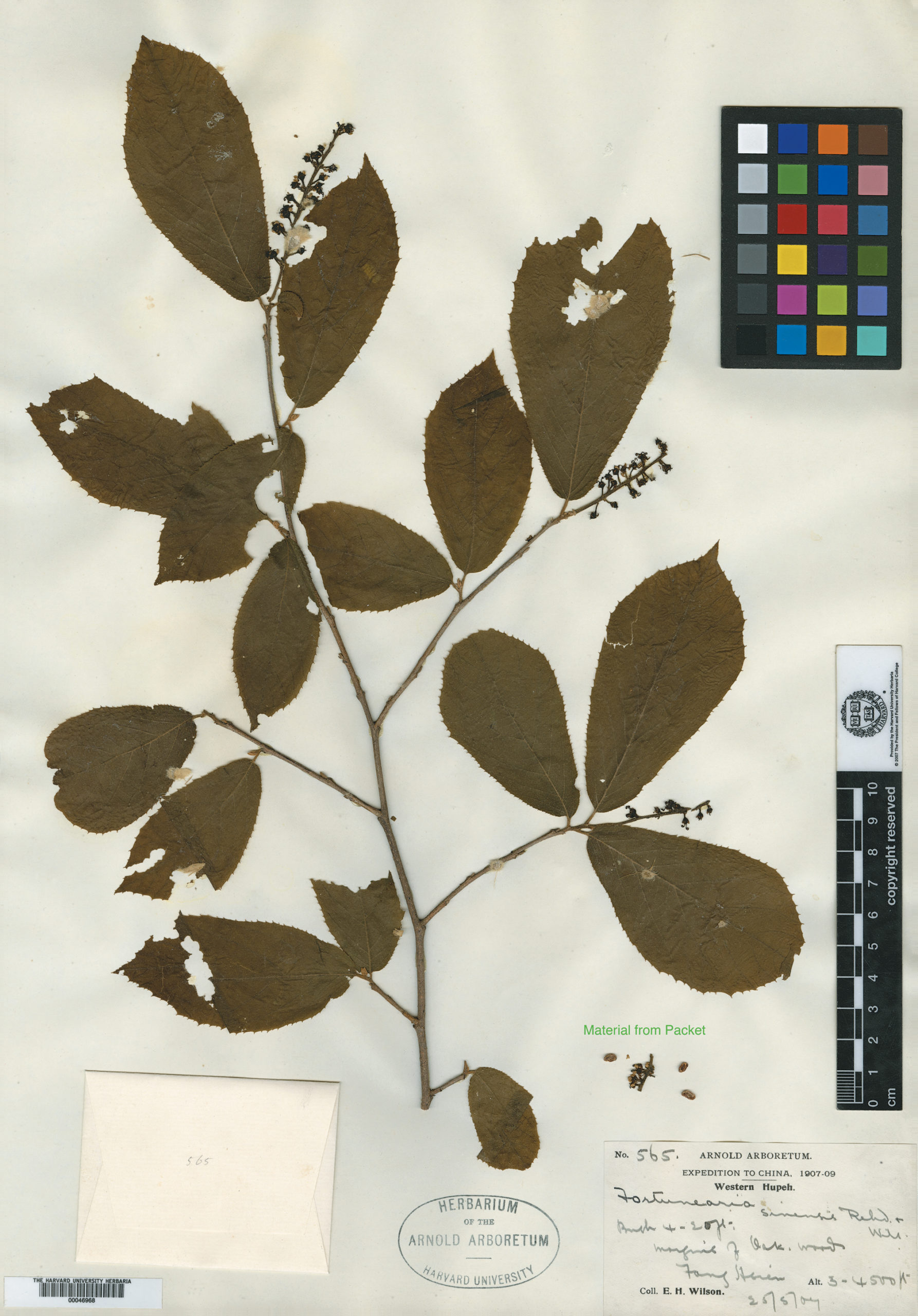

This new Chinese genus is named for the late Robert Fortune whose travels in China and Japan, from 1843–1861 resulted in important additions to our knowledge of the far eastern, and particularly the Chinese flora and enriched our garden with a large number of highly ornamental plants … Fortunearia closely resembles in foliage and habit Sinowilsonia, which differs chiefly in its tubular calyx-tube several times longer than the ovary and enclosing it, by the absence of petals, the larger spatulate sepals, sessile flowers and the flat cotyledons …

Plantae Wilsonianae Volume 1, 1913

As Wilson noted, Fortunearia differs from Sinowilsonia in its reproductive structures. The two species are close cousins on the family tree and again the evolutionary transition from petals to no petals is apparent. A few accessions of Fortunearia sinensis do exist in the Arboretum, most notably a pair growing in the Explorers Garden under the shade of a large Canadian hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) just up the slope from Oak Path. These specimens were received as wild collected seed in 1980 from the Chinese Academy of Forestry. No plants collected directly through Arboretum expeditions currently exist on the grounds; seedlings from Wilson’s original collection survived only a few years in cultivation. Seeds were also collected on the 1994 NACPEC expedition, but no plants resulted. This is another example of an extremely rare plant in cultivation, given its modest ornamental interest.

Winter-hazel

Corylopsis. All the species of this genus of shrubs of the Witch Hazel Family cultivated in the Arboretum have survived the winter with little or no loss of wood, but the flower-buds of the Chinese C. Veitchiana and C. Willmottae, and of the Japanese C. pauciflora and C. spicata have been killed by the cold, and the only species which has flowered is C. Gotoana of the elevated region of central Japan. This is evidently the hardiest of the plants of this genus, and as it has now flowered in the Arboretum every spring for several years there is good reason to hope that we have here an important shrub for the decoration of northern gardens. The flowers are produced in drooping spikes and open before the leaves appear, as in the other species, and are of a delicate canary-yellow color and pleasantly fragrant.

Arnold Arboretum, Bulletin of Popular Information, May 4, 1918

In the early to mid-1900s, the status of the winter-hazels (Corylopsis) was a topic of interest in Arboretum publications each spring. As noted above, the most reliably flower hardy species has been C. gotoana, which some taxonomic references now group with another Japanese montane species, C. glabrescens, under the latter name. There is still much debate about the most appropriate treatment of the Corylopsis taxa. Some references have listed upwards of 30 taxa, though most research today groups many of these together into around ten species. E. H. Wilson even proclaimed his confusion with the genus in field correspondence with Sargent from China dated August 17, 1907: “Corylopsis are exceedingly common shrubs and extremely variable in foliage and degree of hairiness. At present I am undecided as to whether one, two or three species occur …”

All of the species are similar in appearance, growing as multi-stemmed, broad-spreading shrubs of varying size. Of particular ornamental value are the early spring flowers—fragrant, bell-shaped, pale yellow to greenish yellow, and borne in pendulous racemes. Fall foliage color is a rather muted greenish yellow, unimpressive compared with many other family members. There are reports of better fall color farther south; possibly the leaves fall prematurely in colder northern regions.

Corylopsis glabrescens (C. gotoana), reportedly the hardiest species and the most well suited for New England gardens, was first introduced into cultivation by Arboretum dendrologist John George Jack. He sent seeds back to the Arboretum from Japan in 1905, the year he spent touring Northern China, Korea, and Japan as only the second Arboretum staff member (after Sargent) to visit Asia. Another Arboretum connection to the genus came when Wilson and Rehder named several new Corylopsis taxa from the herbarium vouchers Wilson brought back from his early expeditions for the Arboretum. Although some of these Corylopsis have now been lumped together with other taxa, I think Wilson would be pleased to hear that the topic continues to confuse taxonomists even today!

The greatest concentrations of winter-hazel in the Arboretum can be found adjacent to the hickories in the area known as the Centre Street Beds and in the Explorers Garden near the summit of Bussey Hill—a visit to these areas in early spring is certainly worth the trip. A bonsai specimen of Corylopsis spicata can also be seen in the dwarf potted plant pavilion adjacent to the Leventritt Shrub and Vine Garden.

A Family Worth Knowing

The witch-hazel family contains a relatively small number of species (around 100), yet the group is tremendously diverse. Its members are botanically fascinating and carry with them a remarkable history of exploration and discovery. From witch-hazel to winter-hazel, Fothergilla to Parrotia, they are among the most charming of garden plants. Although much work has been done to increase the utility of the family members in our landscapes, their presence remains understated. In New England and many other regions, the plants of Hamamelidaceae fill our gardens with beauty, even in the depths of winter. As has been stated before, there is a tree or shrub in bloom every month of the year in the Arnold Arboretum—a phenomenon only possible because of the witch-hazel family.

Sidebar | A Lone Loropetalum

The sweetgums (Liquidambar spp.) have traditionally been included in Hamamelidaceae, forming the subfamily Altingioideae along with two other genera, Altingia and Semiliquidambar. However, the members of Altingioideae have enough morphological differences from the rest of Hamamelidaceae that some taxonomists through the years have suggested that the group be elevated to their own separate family, Altingiaceae. Recent research at the molecular level supports this separate family, and some (though not all) taxonomic references now list sweetgums under Altingiaceae rather than Hamamelidaceae. The Arboretum has accessions of three Liquidambar species in the collection: L. styraciflua from North America, and L. acalycina and L. formosana, both from China. This large specimen of L. styraciflua (135-38-B) grows near the juncture of Bussey Hill Road and Valley Road.

Sidebar | A Missing Gem

Disanthus cercidifolius is a witch-hazel family member that is, unfortunately, missing from the Arboretum collection. This large shrub from China and Japan is noted for its attractive heart-shaped leaves; the specific name cercidifolius alludes to their resemblance to the leaves of Cercis, the redbuds. Like several of its relatives in Hamamelidaceae, Disanthus has excellent fall foliage color featuring rich shades of red and purple.

The Arboretum has accessioned this species a number of times but we currently have no living specimens. Some seed accessions had poor or no germination, and unfavorable climate or site conditions may be responsible for other failures. Arboretum Curator of Living Collections Michael Dosmann reports that Disanthus cercidifolius is high on his “wanted” list, and future accessions will be carefully sited to provide the fertile, moist, well-drained soil, partial shade, and wind protection that this plant prefers.

References

Anderson, E. and W. H. Judd. 1933. Fothergilla major. Bulletin of Popular Information. ser. 4. vol. 1, no. 12.

Arnold Arboretum. 1918. Effects of the severe winter. Bulletin of Popular Information. vol. 4 no. 1.

Bennett, E. S. (ed.). 2000. 2001 PIPD releases, in Arnold Arboretum News. Arnoldia 60(4).

Darke, R. 2008. Fothergilla in cultivation. The Plantsman. 7(1): 10–17.

Dirr, M. A. 2009. Manual of woody landscape plants. Champaign, IL: Stipes Publishing.

Dirr, M. A. 1983. Manual of woody landscape plants. Champaign, IL: Stipes Publishing.

Endress, P. K. 1993. Hamamelidaceae. In: K. Kubitzki, J. G. Rohwer, and V. Bittrich (eds.), The families and genera of vascular plants, vol. 2, page 324. Berlin-Heidelberg-New York: Springer-Verlag.

Faull, J. H., J. G. Jack, W. H. Judd, L. V. Schmitt. 1934. Winter hardiness of trees and shrubs growing in the Arnold Arboretum. Bulletin of Popular Information. ser. 4. vol. 2, no. 7: 29–36.

Hemsley, W. B. 1906. Sinowilsonia henryi, Hemsl. Hooker’s Icones Plantarum 29: t. 2817.

Li, J. and A. L. Bogle. 2001. A new suprageneric classification system of the Hamamelidoideae based on morphology and sequences of nuclear and chloroplast DNA. Harvard Papers in Botany 5: 499–515.

Li, J., A. L. Bogle, and A. S. Klein. 1999. Phylogenetic relationships of the Hamamelidaceae inferred from sequences of internal transcribed spacers (ITS) of nuclear ribosomal DNA. American Journal of Botany 86: 1027–1037.

Li, J. and P. Del Tredici. 2008. The Chinese Parrotia: A sibling species of the Persian Parrotia. Arnoldia 66(1): 2–9.

Nicholson, R. G. 1989. Parrotia persica: An ancient tree for the modern landscape. Arnoldia 49(4): 34–39.

Ranney, T. G., N. P. Lynch, P. R Fantz, and P. Cappiello. 2007. Clarifying taxonomy and nomenclature of Fothergilla (Hamamelidaceae) cultivars and hybrids. HortScience 42: 470–473.

Rehder, A. 1920. New species, varieties and combinations from the herbarium and the collections of the Arnold Arboretum. Journal of the Arnold Arboretum 1: 256–263.

Sargent, C. S. 1895. New or little-known plants. Fothergilla Gardeni. Garden and Forest. 8: 446.

Citation: Gapinski, A. 2015. Hamamelidaceae, part 2: Exploring the witch-hazel relatives of the Arnold Arboretum. Arnoldia, 72(4): 20–35.

Spongberg, S. A. 1991. A Sino-American Sampler. Arnoldia 51(1): 2–14.

Watson, W. 1896. Foreign correspondence: London letter. Parrotia Jacquemontiana. Garden and Forest. 9: 173–174.

Weaver, R. E. 1969. Studies in the North American genus Fothergilla (Hamamelidaceae). Journal of the Arnold Arboretum. 50: 599–619.

Weaver, R. E. 1981. Hamamelis ‘Arnold Promise’. Arnoldia 41(1): 30–31.

Weaver, R. E. 1976. The witch hazel family (Hamamelidaceae). Arnoldia 36(3): 69–109.

Wilson, E. H. and C. S. Sargent (ed.). 1913. Sinowilsonia. Plantae Wilsonianae. Vol. 1. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Andrew T. Gapinski is Manager of Horticulture at the Arnold Arboretum.