By David Foster, Rick Lewandowski, Rebecca Oreskes, Seana K. Walsh, Kenneth R. Wood, and Rohan Press

The magnitude of federal funding in landscapes, ecosystems, and communities is measurable, but its effects can be hard to feel firsthand. The occasional headline about an endangered species; the broad brim of the rangers’ hat on vacation; the agency stamps at the bottom of a wildlife-refuge sign glimpsed along a highway—these are occasional impressions, which rarely endurably register. As the first federal funding cuts landed in March of 2025, it struck us that the power of this tradition of federal stewardship (for it is a tradition, as well as a matter of law and policy) lies in this very transparency, familiarity, and ubiquity. The Clean Water Act and the Endangered Species Act; the New-Deal commitment to federally-funded horticulture, conservation, and landscape work; the Organic Act of 1897, which laid the groundwork for the National Forest Service and the National Park Service: down through this history, one finds expressed—first fitfully and then with great force—a commitment to doing the work of the land together. Taken as a whole, federal funding isn’t a list of programs on a spreadsheet; it’s a world of beautiful landscapes and thriving ecosystems, of extraordinary trees not only in managed and preserved landscapes, but in our own gardens. It is a world of intergenerational commitment to preservation, interpretation, and care—one which, though we take it for granted, is worthy of our celebration and, in the midst of its loss, our grief.

Current federal funding for basic science at Harvard has been terminated, including work on response of trees to climate change done here at the Arnold Arboretum. (This situation is highly fluid, subject to litigation and policy change, and may be different by the time we go to press.) As Michael Dosmann points out in his column at the front of this issue, the Arnold is part of the world federal stewardship has made, through federal support for longstanding collections, horticultural work, archival programs, and basic science. How to make this world of stewardship visible before it is damaged irreparably? How to highlight the importance of federal support of collections, research resources, landscapes, and ecosystems? To help us grapple with these questions, we invited some of the people who’ve done the work of this world to share stories that epitomize the importance of federal stewardship, indicate the richness and impact of the work, and suggest the scale of possible loss, especially in the realms of ecology, forest management, horticultural research, and basic science. —Arnoldia

1985: Long-Term Ecological Research and the Transformation of the Harvard Forest

by David Foster

Friends Day September 1985 was the darkest day at the Harvard Forest. To gathered supporters, alums, students, and staff, Director John Torrey unveiled a contingency plan to “shutter the Forest as a department,” move the administration and research to Cambridge, and manage the Petersham facilities as a field station. Beginning the third year of a five-year junior faculty appointment, I absorbed the explanation: termination of fifty years of funding from the Cabot Foundation, waning support from Harvard, and aging senior faculty. We needed grants, donors, or divine intervention.

Lacking connections to advance the last two options, I concentrated on convincing the National Science Foundation (NSF) that the unrivaled knowledge accumulated through seventy-five years of study on 3000 acres in central Massachusetts provided the ideal laboratory to address critical questions on the future of forest ecosystems. A year later, the rejection of my first grant proposal was still weighing heavily on my mind when opportunity literally walked in the back door of Shaler Hall.

Jerry Melillo, Director of the Ecosystem Center in Woods Hole, had been conducting studies on nitrogen and carbon cycling in our forests for a decade, but this was our first encounter. He sat down with John Torrey, Ernie Gould, and me to gauge the Forest’s interest in a longshot—to compete nationally to become one of a handful of Long-Term Ecological Research (LTER) sites sponsored through renewable six-year NSF grants. Melillo was heading to a two-year stint at NSF and had good insights into the program. He viewed the Harvard Forest’s deep archive of data, facilities, and land base as ideally suited for integrated ecological studies. Moreover, he could envision the perfect team to complement his work and our Forest group: John Aber, ecosystem scientist and modeler at University of New Hampshire; Steve Wofsy from Harvard, atmospheric scientist with novel technology to measure forest carbon dynamics; Fakhri Bazzaz, to investigate plant-environment interactions; and Richard Forman, leader of the new field of landscape ecology. John Torrey agreed to lead this major proposal, and that afternoon I called each of my new Harvard colleagues and began reworking that rejected NSF proposal.

The LTER program became a magnet attracting scientists, students, and practitioners to Petersham. It became the glue that held all comers and the institution together. It also became a multiplier, increasing NSF’s annual investment more than an order of magnitude through state, federal, foundation, and philanthropic funds.

The project to contrast the responses of forest ecosystems to physical disturbances such as hurricanes and logging and to novel anthropogenic stresses such as acid rain and climate change was funded in 1988 and is just entering its final year (editor’s note: this termination occurred before the current administration took office). That series of seven grants fueled a transformation of the Harvard Forest from a delightful-but-struggling backwater to one of the world’s leading ecological research centers. Yet it was not the size of the award that mattered. The initial grant of $600,000 was modest when split among more than a half dozen major research groups. Instead, it was the sustained commitment by the agency and the scientists that fueled cohesion, novelty, and growth.

As a department, the Harvard Forest pivoted and integrated all its programs and staff to support the LTER theme. As faculty retired, we created senior scientist positions, hiring superb colleagues who sought to collaborate, complement, and integrate into a team addressing major scientific questions that had tangible relevance to land management, conservation, and planning. Each of the outside research groups operated independently but with a strong focus on our collaborative goals. The collective power of all these researchers and the scientific infrastructure they built attracted hundreds from around the world to add studies, magnifying the effort.

The LTER program became a magnet attracting scientists, students, and practitioners to Petersham. It became the glue that held all comers and the institution together. It also became a multiplier, increasing NSF’s annual investment more than an order of magnitude through state, federal, foundation, and philanthropic funds. To young scientists like me, LTER brought mentors, superb colleagues, and students who shaped our careers. And every year the researchers and Harvard Forest community celebrate with an uplifting annual meeting that offers great promise for the future.

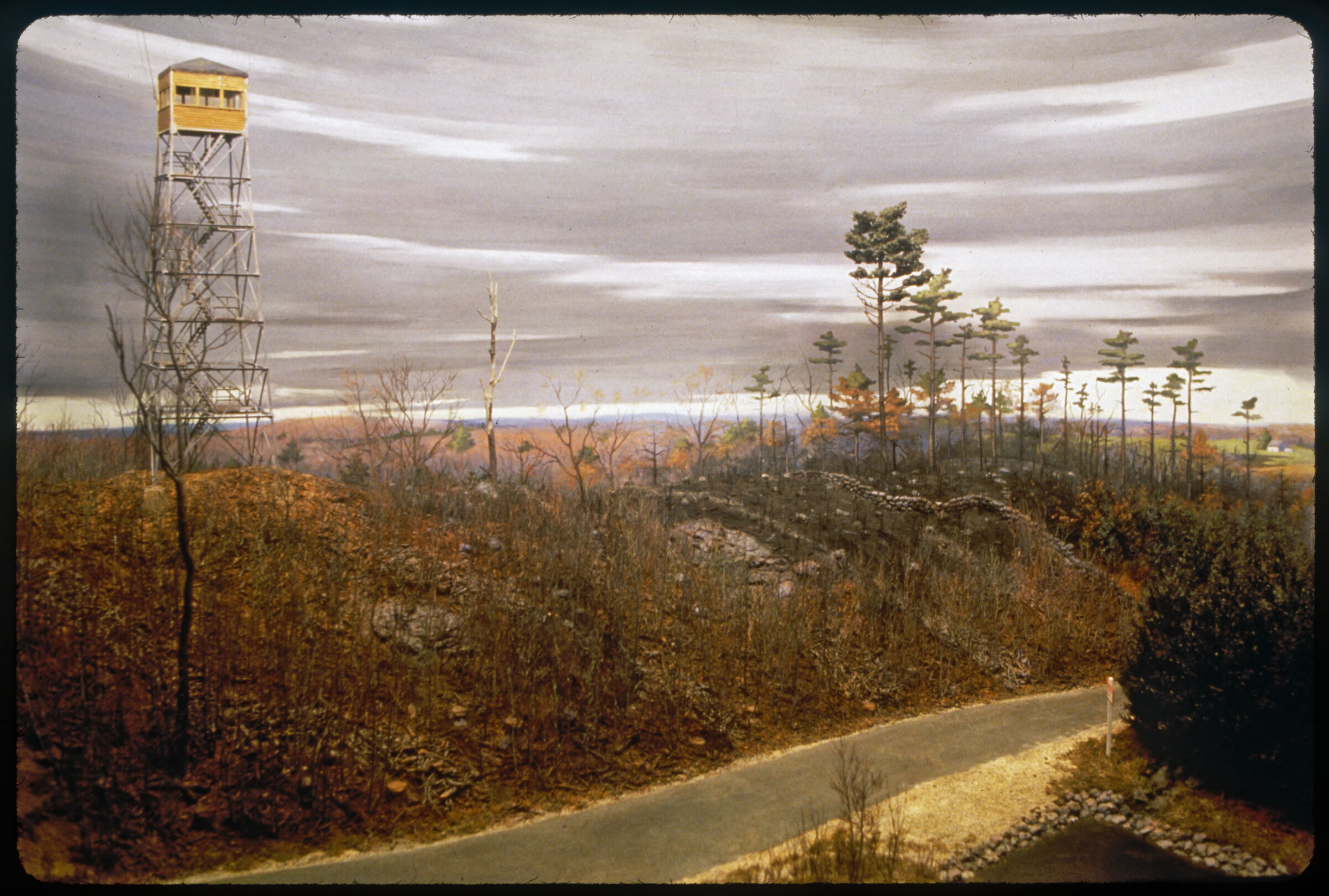

1990: How Much Does It Cost to Buy a Mountain?

by Rebecca Oreskes

In 1990, in the early years of my US Forest Service career, my then-boss sat me down to talk about the Forest Service mission. I was a young Public Information Specialist and he wanted to be sure I understood the idea of “multiple-use”—that the Forest Service was here to balance many different aspects of the land, and that while the land comes first, that didn’t mean forsaking the community. Our job was to listen to people, to understand their concerns and, somehow, to juggle the conflicts in a great dance, balancing both long and short-term benefits. It was also important to keep in mind that the multiple-use mission didn’t mean that every acre of land had to be treated the same: some areas might be appropriate for harvesting timber; other places were best stewarded for recreation use or designated wilderness. He made clear that the mission wasn’t easy. But it was rewarding.

I learned this lesson continually over my 25-year career in the Forest Service and on the White Mountain National Forest (WMNF). From seasonal employment as a campground attendant, and a wilderness and backcountry ranger; to permanent work in recreation and timber marking, to a public affairs specialist and recreation and wilderness program leader for the WMNF. Beyond the borders of New England, I was chair of the chief’s national wilderness advisory group and part of the FS international disaster assistance support team in cooperation with USAID. I ended my career as a staff officer on the White Mountain National Forest Leadership team.

Our job was to listen to people, to understand their concerns and, somehow, to juggle the conflicts in a great dance, balancing both long and short-term benefits.

What every position had in common was a sense of relationship. Relationship between people and the land we all “own.” My boss was right to tell me early in my career that the FS multiple-use mission wasn’t an easy one. For every citizen who wants more designated wilderness, there is someone who wants more timber production. For everyone who wants more opportunities to recreate, there is a voice asking for more consideration for wildlife. And clean water amid human use doesn’t just happen—it takes care to protect the watersheds in which national forests exist.

Over my career, I also saw that it’s possible to look at multiple use as a purely transactional endeavor. We can get this many board feet, this many miles of hiking trail, this many miles of snowmobile trail. But I come back to the idea that my work was always about relationships: with the land, and with each other as citizens. We can look at national forests not just as producers of commodities, but as a shared responsibility in caring for what helps give us clean water, places to recreate, homes for wildlife, wilderness, and wood products.

I have another memory from my early days of Forest Service work. A co-worker and I were leading a group of adjudicated youth in building cairns above treeline on the eastern slope of Mt. Washington. The cairns were meant to help hikers find the trail and to keep them from trampling fragile alpine flowers. For these young men, working with us was an alternative to juvenile prison. It was a perfect, clear day with what felt like unlimited visibility. As we took a break from the demanding work of moving heavy rocks, one of the young men asked, “How much does it cost to buy a mountain?”

The mountains had touched him just as they’d touched me only a few years earlier. We tried to answer his question by explaining that he was looking out over public land. It was land all of us owned together.

But I come back to the idea that my work was always about relationships: with the land, and with each other as citizens.

When hikers are sweating their way up to the iconic White Mountain alpine zone, they’re unlikely to think about the work that went into making the trail, about the young man who helped move rocks to build cairns. They’re not likely to think much about the habitat for the birds they hear or the unglamorous planning and monitoring done to protect both the land and the experiences they are having. They’re not thinking about the physical work of picking up trash and cleaning toilets. Mostly, the work gets celebrated quietly, in the satisfaction of a job well done, juggling the many demands of multiple-use land management. Still, I hope people can notice how much effort it takes to care for public land. And I hope we notice before it’s gone.

1990–present: Tapping Underrepresented Diversity

by Rick Lewandowski

After more than 35 years of fieldwork across the eastern and southern United States, I am continually amazed by the extraordinary plant diversity found in nature. These efforts would not be possible, though, without the guidance of dedicated experts and professional colleagues at USDA who have opened doors to gain access to locations where this diversity still thrives.

Much of this work—conducted in support of USDA conservation and horticultural efforts—has focused on documenting and collecting seed of plants for representation in living collections across the US, distribution to researchers and industry, and for long-term ex situ seed storage. Recent expeditions to the southeastern US and Gulf Coast have allowed us to gather under-represented plant diversity, especially from populations on the outer margins of their native ranges.

There remains so much to learn about genera such as Aesculus, Calycanthus, Clethra, Hydrangea, Kalmia, Hamamelis, Ilex, Lyonia, Pieris, Rhododendron, Stewartia, Styrax, Tamala (formerly Persea), Xanthorhiza, Zenobia, and many others. For example, recent fieldwork has resulted in numerous collections of Ilex ambigua, I. cassine, I. coriacea, I. decidua, I. glabra, I. laevigata, I. longipes, I. myrtifolia, I. opaca, I. verticillata, and I. vomitoria. This work also led to the discovery and seed collection of a new population of the state-rare Ilex amelanchier in western Florida.

Many plant populations at the edges of their ranges are at risk of disappearing, though, without the continued commitment of state and federal partners to conserve biodiversity ex situ.

Several plants—some common or only marginally available in horticulture—deserve further study for their hardiness and adaptability. A few include: Aesculus parviflora, Chionanthus virginicus (ecotypes), Cornus alternifolia, Hydrangea quercifolia, Hydrangea cinerea, Illicium floridanum, Kalmia carolina, Kalmia latifolia, Leucothoe fontanesiana, Lyonia ferruginea, Magnolia pyramidata, Pieris phillyreifolia, and Zenobia pulverulenta, just to mention a few.

Additionally, we have documented and shared locations of rare taxa—including Pinckneya bracteata, Litsea aestivalis, Sideroxylon spp., and Fothergilla spp.—with state natural area specialists. Many plant populations at the edges of their ranges are at risk of disappearing, though, without the continued commitment of state and federal partners to conserve biodiversity ex situ.

As we continue to explore the habitats of our native flora, it becomes increasingly clear that we must document and preserve North America’s precious plant diversity with the same dedication we have historically applied to agronomic crops. This is not only an opportunity to conserve valuable genomic variation but also to support efforts to identify regionally adapted native taxa for the horticultural industry—an industry that continues to rely on USDA-led research.

2024: Safeguarding Ochrosia kauaiensis

by Seana K. Walsh and Kenneth R. Wood

On the Hawaiian island of Kaua‘i, a rare, single-island endemic tree species is receiving a much-needed lifeline thanks to a collaborative conservation effort and support from the APGA–USFS Tree Gene Conservation Partnership. Ochrosia kauaiensis or hōlei in Hawaiian, a member of the Apocynaceae (milkweed) family, has a confirmed fewer than 100 individuals remaining in the wild. These scattered subpopulations—found in remote valleys, ridges, and slopes in the island’s north and northeast regions—face increasing pressure from invasive plants and animals, likely contributing to the species’ decline and lack of natural regeneration.

In response to these threats, the National Tropical Botanical Garden (NTBG) launched a multi-phase, multi-institution conservation initiative to safeguard this beautiful, rare tree. Because O. kauaiensis produces recalcitrant seeds—meaning they do not survive drying or freezing for conventional seed storage—ex situ collections must be maintained as living plants in nurseries and botanical gardens or in tissue culture labs.

Over the course of seven field expeditions, NTBG and partners—including the Hawai‘i Department of Land and Natural Resources Division of Forestry and Wildlife and the Plant Extinction Prevention Program—journeyed into remote areas to map, tag, and collect seeds and DNA samples from 30 individual trees. Each tree was documented using Hawai‘i’s standardized population reference code system, ensuring accurate provenance for long-term tracking and monitoring. Seeds were propagated at NTBG’s Conservation and Horticulture Center, with plants established at NTBG’s McBryde and Limahuli Gardens on Kaua‘i and at Kahanu Garden on Maui. Seeds were also sent to the Montgomery Botanical Center in Miami, Florida. In a few cases, immature fruits were collected—particularly when regeneration at the site was unlikely due to severe habitat degradation—and sent to the Micropropagation Laboratory at Lyon Arboretum’s Hawaiian Rare Plant Program on O‘ahu. These collaborative efforts have contributed to building a robust metacollection designed to safeguard the species from extinction.

Living plants from the collections continue to be maintained both in Hawai‘i and Florida as a future seed source for restoration efforts, and these metacollections are contributing to further innovations in applied conservation work. NTBG’s Plant Records Manager is adapting and testing a database tool for gap analysis as part of his master’s thesis at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. By overlaying wild collection points and existing ex situ data, the tool helps identify which subpopulations are underrepresented in current collections and prioritize future efforts, including targeted reintroductions. Additionally, living collections of O. kauaiensis are now being used in pollen conservation research, led by NTBG’s scientific curator of seed conservation, to determine how long viable pollen of the species can be stored—a crucial step toward enabling strategic breeding across space and time among metacollection holdings. Field data from the expeditions also informed a long-overdue update to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species assessment, conducted by NTBG staff, which reclassifies O. kauaiensis as Critically Endangered.

The story of Ochrosia kauaiensis is a powerful example of how federal conservation programs—like the APGA–USFS Tree Gene Conservation Partnership—can empower institutions to protect our planet’s species. Thanks to these collaborative efforts, there is renewed hope that this critically endangered tree may one day flourish again in its native forest, supported by the continued dedication of conservationists, scientists, and federal partners.

2025: You Can’t Go Home Again

by Rohan Press

I spent the last two summers working with the Colville National Forest in the Pend Oreille Valley of Washington’s northeast corner, a river valley which has since become the most intimate place to me on earth. I’ve driven nearly its every road and visited its every trailhead. And yet, even then, I feel like something in it, now and ever, eludes me. Maybe that’s partially because I’ve seen it strictly in its splendid summers—not the red and yellow glow of heather and tamarack in autumn, not the fragile eruptions of lanceleaf springbeauty in April, nor least of all the utter transubstantiation of its smothered landscape in winter, Pend Oreille County receiving the most annual snowfall in the state. But it certainly also has something to do with the fact that I won’t be able to return to the Valley for the third time around, this summer, nor for any season in the foreseeable future, due to the paucity of federal funding. I can try to console myself by remembering that no one can ever really know a place fully, and that maybe the distance we will always have from it is part of what keeps us enchanted by it. Nonetheless, it’s a strange feeling, to carry a place so close to my heart that I know I only partially belong to, but which I cling to even more desperately in my absence from it, and doubly so in the face of my estrangement from any cultural world in which it might be shared and recalled.

We all affix ourselves to romantic myths, and the Forest Service was one to which I thought I was willing to dedicate my life.

Indeed, the Valley is forgotten even to most Washingtonians, especially those westsiders who seem to believe that everything east of the Cascade crest is an apple-producing, nuclear-testing desert. Now that I’m living in Massachusetts, the lower Pend Oreille country seems even more infinitely unintelligible: I’ve not met a soul, out here, who knows of it, or who understands its ecology and geology—who understands that it is home to the only population of woodland caribou in the Lower 48, and to Washington’s only grizzly bears; who understands what it means to live in a valley pointed and oriented northbound, all its water destined for Canada—a place where downstream, paradoxically, means more rugged topography, means a rushing, furtive gorge, means higher flanking peaks, until you hit the lonesome Salmo-Priest Wilderness, nestled up against the Idaho and Canadian lines; who understands that when you get close enough to Idaho, the big cedars and hemlocks start up again—North America’s only inland temperate rainforest. I’m now attending a University with triple the population of the entire Pend Oreille County (a county, I like to say, so rural that it doesn’t even have a single traffic light)—and everything about that University is asking me to forget that the Pend Oreille Valley even exists, asking me to renounce it, and some days, and maybe more and more often, lately—as a sort of defense mechanism against its evaporation—I think I’ve been tempted to renounce it. But I could spend this whole essay disowning it, and it would still be abundantly clear that it isn’t yet ready to disown me. Once you see those giant cedars down the South Salmo drainage, you’re a changed man, and something of them you’ll just never be able to let go.

[I]t’s a strange feeling, to carry a place so close to my heart that I know I only partially belong to, but which I cling to even more desperately in my absence from it

Maybe the Valley hasn’t let go of me, but the world has told me I can’t really return to the Valley. And yet the thing is—even if the Colville would have me back, I’m not sure I’d want to go back. One of my deepest lessons working for the Forest Service is that a landscape is only as good as the people in it. But the people are all gone: Mitchell and Adrian, from the fire crew, with whom I’d play guitar at night and wax philosophical about life; Sam and Amelia, up at Sullivan Lake, who’d bake with me and swim with me and make me feel like I belonged, like I had a home; Carol, with whom I could be so vulnerable, with whom I loved to talk about my romantic

hopelessness, and who connected me back to New England’s northern hardwoods; Micah, from Texas, reticent, but with whom I always felt a kind of deep spiritual connection, especially through his tremendous music taste (Boz Scaggs, Charley Crockett); Ken, in his sixties, with his “Washington Wildlife” license plates, who’d worked for the Colville his whole life, who loved Black Sabbath’s debut, and who would tell me endless stories of camping out in the Salmo as a wilderness ranger (a job that was cut during the Bush administration); Sarah, the wildlife biologist, exceedingly kind and a mother to boot, who had once lived in a school bus at the top of a mountain—and Rianna, who would commute up from Spokane every morning—an hour’s drive north in a series of cars and vans that would always seem to break down before long, but which she would always find time to adorn with a wall of stickers on the back window; Rianna, who became, out of all of them, the person I was closest to, and with whom I could share with equal comfort both frank words and tender silence. I worked with Rianna most every day, scoping out damaged meadows and illegal OHV stream crossings, building fences, felling trees, hiking closed roads, collecting grizzly bear hair samples, and calling for endangered goshawks. It’s a rare kind of closeness that comes from working with someone ten hours a day, four days a week, for months at a time. But Rianna—and Sarah—and Micah—and all of these dear, dear friends—they’re all gone from the Colville now, even though many of them thought they were hired as permanent employees. Some of them finished the season with me and are, unlike me, moving on with their lives; some of them were let go by the Forest Service under the new administration; and some of them, like Rianna, left of their own accord, preemptively (she left to work for the state)—escaping the caprice of the federal government before it was too late. They’re all gone—and there’s no getting them back—and so, there’s no going back.

I have always thought of American federal land management as the best, most romantic, and most enduring form of conservation, maybe in the world. I never thought I would use that word, “caprice,” to describe it. For me, the Forest Service always carried the ring of such a noble history, through Roosevelt, Pinchot, Muir, Powell, etc., of course, but then also through a second layer of names, in the literary circuit—Norman Maclean, Aldo Leopold, Gary Snyder, William Stafford, all of whom worked with the National Forest system. My sense of federal lands as “secure” in their conservation, of federally-designated wilderness as the noblest and most immutable form of protection, of the National Forest system as the symbol of mixed-use land management in a way that could bridge political and economic divides—that whole way of thinking has now come unmoored. Rianna’s intuition that there was more security in state management, rather than federal management, goes against every intuition I have ever had, but that is self-evidently the new way of things.

My sense of federal lands as “secure” in their conservation, of federally-designated wilderness as the noblest and most immutable form of protection, of the National Forest system as the symbol of mixed-use land management in a way that could bridge political and economic divides—that whole way of thinking has now come unmoored.

We all affix ourselves to romantic myths, and the Forest Service was one to which I thought I was willing to dedicate my life. But like Thomas Wolfe said: you can’t go home again. To go back to the Forest Service, even if I could, would just to be to succumb to an illusion that I could achieve a kind of intimacy with that valley that I’ll never be able to achieve—especially in the face of the loss of the people that made that place what it is. Without them, the valley isn’t really the valley; its cedars may still beckon, but they can’t really keep their promise; they can’t really hold me anymore. And so I really do think it’s time to move on—to keep a sort of anchoring in that valley, yes, but also to not cling to it or pretend that it could be the way it was, again; and I’ve been trying to think about the lack of government funding as the push I need so as to not fall back onto the consolation and temptation of old myths. Maybe I should mourn the withdrawal of that funding more emphatically—but, the fact of the matter is, I’m trying to see it for myself as something really needful, the closing of one door as the prerequisite for the opening of another. That doesn’t mean I don’t miss it like hell, and won’t continue to; it doesn’t mean I shouldn’t try to hold on. When I think back to it, I feel like I could have done it forever, working with Rianna and with the rest of them—learning my Inland Northwest trees and flowers by heart; spying on black bears up the Shedroof Divide every weekend. But then again, I feel sure that I will be doing it forever, in their name and in their absence, even as I carve out the contours of a new life here in Massachusetts, because of the unfinished and unfinishable business I will always have with that valley, no matter how much more time I am able to spend there, and no matter whether I’ll ever work for the Forest Service again. Whatever my day job, wherever I’m living—my heart’s work, and the work meant for my hands, will ever echo with the sound of that lost river, the glassy, Canada-bound Pend Oreille.

DAVID FOSTER is former director of the Harvard Forest. He is an editor of From the Ground Up, the online publication of Wildlands, Woodlands, Farmlands, and Communities, a conservation collaborative based in New England. Existing LTER programs have not been in the first round of direct spending cuts. On April 30 however, NSF staff were ordered to cancel all future program allocations. The Trump administration’s proposed budget for FY 2026 would cut funding for the NSF by about 55 percent.

REBECCA ORESKES retired from 25 years in the Forest Service in 2013. In February, the White Mountain National Forest lost 11 staff members; in April, the USDA issued a memo directing the USFS to increase timber harvest in some 60 percent of the lands they manage, and to eliminate most environmental assessment and public-comment measures in the process.

RICK LEWANDOWSKI has been a leader at the Morris Arboretum, Mt. Cuba Center, and the Shangri-La Botanical Gardens and Nature Center. The administration’s 2026 budget proposal cuts USDA funding by 18 percent of its current level. According to Reuters, the department has lost more than 15,000 employees to the administration’s incentivization to leave federal employment, nearly 15 percent of the workforce.

SEANA K. WALSH is a conservation scientist and curator of living collections at the National Tropical Botanical Garden.

KENNETH R. WOODS is a research biologist at the National Tropical Botanical Garden.

ROHAN PRESS is an alumnus of the Harvard Divinity School (MTS 2025). This summer, he will serve as an interpretive ranger at Great Brook Farm in Carlisle, MA.