Personalities Associated with the Early History of the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University 1872-1927

Boston, Harvard, and the 1000-Year Lease

In order to serve the dual purpose he believed the Arboretum would have, Charles Sprague Sargent had to persuade the City of Boston and Harvard College to undertake a joint financial venture. His motives were not entirely altruistic; he needed additional money to build and maintain the Arboretum.

The negotiations lasted four years. The Arboretum’s nurseries were bursting at the seams but Sargent could not begin work on Frederick Law Olmsted’s design without commitment from the City. The proposition finally came to a City Council vote in October 1882, but failed to pass. Proponents of the Arboretum quickly moved to set up an Arboretum Committee, and Sargent and Olmsted stepped up their efforts to rally support. A public relations drive was launched that had the “Arboretum Question” debated in the city’s newspapers. Headlines read: “THE ARBORETUM’S VALUE TO BOSTON,” and “AN EDUCATIONAL PARK AT A BARGAIN.” Sargent circulated a petition signed by 1,305 of the most powerful people in Boston. It had a potent effect. A newspaper story from December 1, 1882, read in part:

“The petition … is probably the most influential ever received by that body. It includes almost all of the large taxpayers of Boston. … Nearly all of the prominent citizens are there … The petition would be a prize to a collector of autographs.”

The campaign worked. On December 27, 1882, terms similar to those Sargent had proposed years before were agreed upon. It took a year to work out the details, but on December 20, 1883, a thousand-year lease was signed, and an unprecedented agreement between the City of Boston and Harvard College began.

Under the terms of the agreement, the Arboretum became part of the City of Boston’s park system. The city was to be responsible for the construction and ongoing maintenance of the driveways and boundary fences throughout the Arboretum. Harvard University was to collect the plants, design the Arboretum, and maintain the collections and programs. [Connor, Sheila. “The Arnold Arboretum: An Historic Park Partnership.” Arnoldia 48:4, Fall 1988 [pdf].

In addition to this list of resources, you will also find a wealth of information in Ida Hay’s book, Science in the Pleasure Ground : a history of the Arnold Arboretum, and in our quarterly journal, Arnoldia.

Weld Family | Benjamin Bussey | James Arnold | Asa Gray | Francis Parkman | Charles Sprague Sargent | Horatio Hollis Hunnewell | Frederick Law Olmsted | Jackson Thornton Dawson | Charles Edward Faxon | Alfred Rehder | George Russell Shaw

Weld Family

The Weld family of Massachusetts has included state governors, Harvard benefactors, and other notable figures. The progenitor in America was Captain Joseph Weld (1599-1646). He was born in England and came to New England in about 1633 during the migration of Puritan colonists to Massachusetts Bay. He was probably granted about 278 acres of land in the town of Roxbury for his service as a captain in the Pequot War (1636-1638). His grant included portions of present day Jamaica Plain and Roslindale—land on which the Arnold Arboretum is located today. Weld was an aide to Governor John Winthrop and a deputy to the Massachusetts General Court.

In 1711, Joseph Weld (descendant of Captain Weld) and 44 other men organized the Second Church of Christ on Walter Street. The church once stood on Peters Hill, and behind it to the south, the church burying ground was created. This 0.81-acre parcel is one of Boston’s 15 historic cemeteries and although it is under the purview of the Boston Parks Department, its grounds are maintained by the Arboretum. Few headstones remain, but there are ten Welds, including two who fought in the Revolutionary War and their wives and children, who are buried in this location.

One of his sons, Captain John Weld, inherited his estate and built his home, Weld Hall, on what came to be called Weld Hill, a piece of land across the street from the present-day Forest Hills MBTA station. This parcel is not to be confused with what we now call Weld Hill at the Arboretum—a 14-acre, Harvard-owned parcel which is bounded by Weld and Walter Streets across from Peters Hill (named after Andrew James Peters, a member of the United States House of Representatives from 1907 to 1914, and the Mayor of Boston, Massachusetts from 1918 to 1922).

After Lieutenant Eleazer Weld died in 1800, fellow Revolutionary War veteran Benjamin Bussey purchased approximately 120 acres of the original Weld holdings. Forty years later, Bussey bequeathed this land to Harvard.

READ MORE:

Lehmer, Mary. “The Walter Street ‘Berrying’ Ground.” Arnoldia 21(12), 1961 [pdf].

Benjamin Bussey (1757-1842)

Born in 1757 in Stoughton (later Canton), Massachusetts, Benjamin Bussey served in the American Revolution and achieved the rank of Quartermaster. About 1779 he went into business as a silversmith in Dedham, Massachusetts and he married Judith Bussey in 1780.

By 1792, when he moved to Summer Street in Boston, his business had expanded into trading in a variety of goods. We want to acknowledge that some of the goods Bussey acquired in the Americas for trade in Europe, such as tobacco and sugar, would have been produced by enslaved peoples. Researchers from the Initiative on Harvard and the Legacy of Slavery have not uncovered any mention of Bussey owning slaves himself or of his ownership of any plantations or other property on which enslaved people worked producing materials he later sold in Europe, however research is on-going.

He retired from business in 1806 and turned his interests to farming and manufacturing. With the money he had earned in the triangle trade, he began buying small farmsteads and part of the Weld family holdings which later became the nucleus of the Arnold Arboretum property. Later, Bussey also established woolen mills in Dedham and bought extensive properties in Maine. In 1815 he built a mansion on his Jamaica Plain property where he resided until his death in 1842.

In his will, Bussey created an endowment at Harvard for the establishment of an undergraduate school of agriculture and horticulture to be called the Bussey Institution for the “instruction in practical agriculture, in useful and ornamental gardening, in botany, and in such other branches of natural science as may tend to promote a knowledge of practical agriculture, and the various arts subservient thereto and connected therewith.” Also included in his 1835 will was the grant of his estate “Woodland Hill” in Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts to the President and Fellows of Harvard College which would be the site of the school. A number of years would elapse before Harvard could act upon the bequest.

In 1870, his granddaughter, Mrs. Maria Bussey Motley, released seven acres of the property for the establishment of the school and work began on the Bussey Institution building. By 1871 the Bussey Institution had been established to carry out the terms of the will. At the same time her husband, Thomas Motley, Jr., was appointed instructor of farming, a post he held until his death in 1895. Francis Storer was named professor of agricultural chemistry, and in 1871 Francis Parkman was named professor of horticulture.

READ MORE:

Wilson, Mary Jane McClintock. Master of Woodland Hill : Benjamin Bussey of Boston (1757-1842).

Wilson, Mary Jane.”Benjamin Bussey, Woodland Hill, and the Creation of the Arnold Arboretum.” Arnoldia 64(1) [pdf].

“The Bussey Institution.” Arnoldia 7(3) [pdf].

Archives of the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University. Bussey Institution records, 1872-2007 [pdf].

Gray, Thomas, 1772-1847. A tribute to the memory of Benjamin Bussey, esq., who died at Roxbury January 13, 1842.

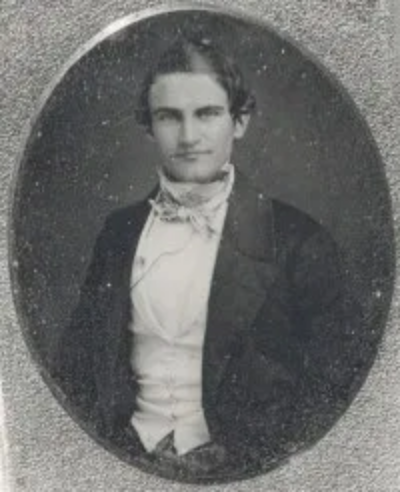

James Arnold (1781-1868)

The son of Thomas and Mary (Brown) Arnold, James was born in Providence, Rhode Island, on September 9, 1781. He came to New Bedford, Massachusetts, to work for William Rotch, Jr., a merchant of the city, whose family had established the whaling industry in New England prior to the American Revolution. Arnold later became a partner and married Rotch’s daughter Sarah on October 29, 1807.

Arnold was among a number of successful businessmen from the area who became interested in agriculture and horticulture and he was one of the founders of the New Bedford Horticultural Society in 1847. In 1821 he erected a Federal style brick mansion in New Bedford and established extensive gardens. He opened his private gardens to the public, at the time an unusual and highly regarded act. In 1868, Unitarian minister William J. Potter called the Arnold mansion “a home the most conspicuous among all our homes for culture, for hospitality, for charity.”

James Arnold died in 1868 in New Bedford, outliving both his wife and daughter. Arnold’s will specified that $100,000 of his fortune should be used to advance agriculture and horticulture. The trustees of his will (Francis E. Parker, trust lawyer, managed charities; George Barrell Emerson, teacher, philanthropist; John James Dixwell, merchant, bank president and Jamaica Plain resident) suggested the sum be transferred to the President and Fellows of Harvard College to found an organization devoted to that purpose. In 1872 the Arnold Arboretum was founded on a portion of the land in Jamaica Plain willed to Harvard by Benjamin Bussey.

Although his extensive gardens are gone, the Wamsutta Club, founded in 1866 for the affluent of New Bedford’s community who came from not only the whaling industry, like Arnold, but the new textile industry, purchased the Arnold Mansion in 1919 and added two large wings on the north and south.

READ MORE:

Raup, Hugh M. “The Genesis of the Arnold Arboretum.” Bulletin of Popular Information, series 4, Vol. VIII, no. 1. April 26, 1940 [pdf].

Hay, Ida. “George Barrell Emerson and the Establishment of the Arnold Arboretum.” Arnoldia 54(3), Fall 1994 [pdf].

Archives of the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University. Arnold Family Collection [pdf].

Asa Gray (1810-1888)

Born in Sauquit, NY, Gray became an MD 1831. In 1842, Gray was appointed professor of natural history at Harvard, a post he retained until 1873. He is considered the father of American botany and instrumental in unifying the knowledge of the plants of North America in his Manual of the Botany of the Northern United States, from New England to Wisconsin and South to Ohio and Pennsylvania Inclusive. Known as Gray’s Manual, it has gone through eight editions and remains a standard in the field.

By donating his book and immense plant collection which numbered in the thousands, he effectively created the botany department at Harvard; the Gray Herbarium which is part of the Harvard University Herbaria is named after him. The Gray Herbarium at its original location on Garden Street in Cambridge is now the home of the Harvard University Press.

READ MORE:

Jenkins, Charles F. “Asa Gray and His Quest for Shortia galacifolia.” Arnoldia 51(4), Winter 1991 [pdf].

Library and Archives of the Gray Herbarium, Harvard University Herbaria. Asa Gray Papers [link].

Powell, Alvin. “Gray gets stamp of approval: Postal Service honors Harvard’s famed ‘closet botanist.’” Harvard Gazette, June 30, 2011 [link].

Francis Parkman (1823-1893)

Francis Parkman was born in Boston, Massachusetts to Reverend Francis Parkman Sr. (1788-1852), and Caroline (Hall) Parkman. A scion of a wealthy Boston family, Parkman had enough money to pursue his research without much worry about finances. His financial stability was enhanced by his modest lifestyle, and later, by the royalties from his book sales. He was thus able to commit much of his time to research, as well as to travel. He traveled across North America, visiting most of the historical locations he wrote about, and made frequent trips to Europe seeking original documents for his research.

A neighbor of the Sargents, Parkman’s estate, called “Sunnyside,” was on the northwest shore of Jamaica Pond. A granite memorial featuring a formal bench with central shaft, from which emerges a forest Indian was erected by friends of Francis Parkman in 1906 at the approximate site.

Parkman has been hailed as one of America’s first great historians and a master of narrative history. However, he was also a horticulturalist, author of The Book of Roses (1866) and the first professor of horticulture in the United States. After a year as Professor of Horticulture at the Bussey Institute Francis Parkman – never healthy – resigned and very well may have suggested his young neighbor as not only his successor at the Bussey Institution, but a candidate for director at the newly created Arnold Arboretum.

READ MORE:

Whitehill, Walter Muir. “Francis Parkman as Horticulturist.” Arnoldia 33(3), May/June 1973 [pdf].

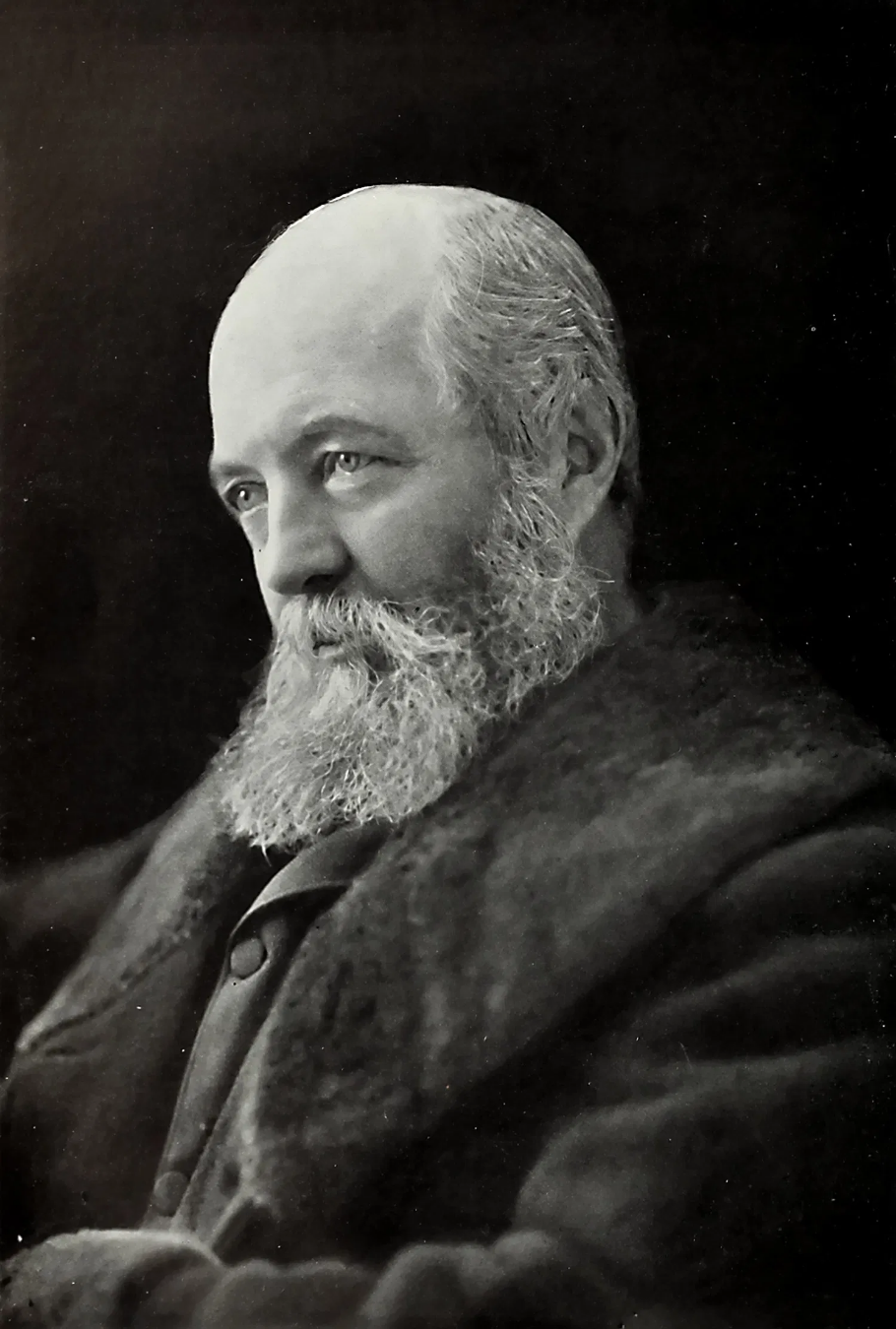

Charles Sprague Sargent (1841 -1927)

Sargent, the Arboretum’s first director, served the institution for over 54 years. He was the child of Henrietta Gray and Ignatius Sargent, a successful Boston merchant, banker, and railroad financier. He graduated from Harvard College in 1862. During the American Civil War, he served in the Union Army, and was brevetted major by the end of the conflict. From 1865-1868, he toured the gardens of Europe and then returned to Boston to manage his father’s estate Holm Lea in Brookline, Massachusetts.

In 1872 he was appointed Director of the Harvard Botanic Garden, becoming in effect an apprentice to Asa Gray. This position included the administration of the Bussey Institution as Professor of Horticulture, thus becoming Francis Parkman’s successor. On November 24, 1873, Sargent received his ultimate charge as the Director of the Arnold Arboretum. He held all three positions concurrently for several years but divested himself of them to concentrate on the planning of the landscape and plantings of the Arnold Arboretum with Frederick Law Olmsted and his management of the census of American trees in 1880. In spite of James Arnold’s generous bequest to fund an arboretum, Sargent knew that he did not have the financial resources to do everything he would like with the plants and grounds. He therefore devised a plan for Harvard University to give the lands on which the Arnold Arboretum was located, to the City of Boston to be part of the Boston park system, and then lease them back on a 1000-year lease. The City would build and maintain all the infrastructure and Harvard would take care of the trees and natural landscape. After much wrangling, the plan was accepted in 1883 and the City began the long process of building the hardscape. When Sargent assumed the directorship of the Arnold Arboretum there were no buildings on the site except for Benjamin Bussey’s mansion which was still occupied by his heirs. Dwight House on Sargent’s estate headquartered his library, herbarium, and first administrative offices of the Arnold Arboretum until 1892 when the Hunnewell Building was constructed on the Arboretum’s grounds. Sargent’s gave his personal library to the institution to be housed on the third floor of the new building.

During this period Sargent was also working on his Silva of North America. The first volume was published in 1891 and thirteen more volumes would follow over the coming years. He also conducted the publication of the weekly periodical Garden and Forest. This groundbreaking publication was an intersection of current thought and opinion on gardens, landscape design, horticulture, and forestry, as well as being an unofficial organ for the Arnold Arboretum. In 1892, Sargent visited Japan and saw so himself the richness of the Asian flora. A trip around the world in 1903 that included a stop in China, cemented in his mind the need for a collector to spend several seasons in China gathering plant specimens, seeds, and cuttings for shipment to the Arboretum. He hired Ernest Henry Wilson for that position in 1906. Wilson was an experienced collector having spent the better part of 1899-1905 collecting in western China for the Veitch Nursery Company. He made two sucessful trips to China for the Arboretum from 1907-1911, and returned to explore Japan, Korea, and Taiwan between 1914 and 1919. The plants Wilson and other collectors gathered in Asia swelled the collections and were shared with other botanic gardens and arboreta worldwide. Sargent was actively involved with running the Arboretum until the end of his long life. Well into his eighties he could still be found in his office in the Hunnewell Building, in the library examining plant specimens, or out on the grounds directing the planting of a tree. He guided the institution with a firm hand until his death in 1927.

READ MORE:

Garden and Forest; A Journal of Horticulture, Landscape Art and Forestry, conducted by Charles Sprague Sargent, 1888-97.

Archives of the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University. Charles Sprague Sargent (1841-1927) papers, 1868- [pdf].

Sutton, S.B. Charles Sprague Sargent and the Arnold Arboretum. Harvard University Press, 1970.

Rehder, Alfred. “Charles Sprague Sargent.” Journal of the Arnold Arboretum. 17(2), April 1927 [pdf].

The One-hundredth Anniversary of the Birth of Charles Sprague Sargent, published in Arnoldia (1941) [pdf].

![Horatio Hollis Hunnewell. Distinguished horticulturist and builder of the Arnold Arboretum Administration Building. Born July 27, 1810, died May 20, 1902. [Information from verso of mount].](https://arboretum.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Screenshot_2020-07-08-003-jpg-WEBP-Image-200-×-235-pixels.png)

Horatio Hollis Hunnewell (1810-1902)

H. H. Hunnewell was a wealthy banker, railroad financier, philanthropist, amateur botanist, and one of the most prominent horticulturists in America in the nineteenth century. Practicing horticulture for nearly six decades on his estate in Wellesley, Massachusetts, Hunnewell made a donation in 1873 that helped Asa Gray revise and complete his Flora of North America. He also funded the conifer collection at the Arboretum and in 1892 donated the Arboretum’s administration building known then as the Museum.

Sargent conferred with Hunnewell often as he made plans for the Arboretum. The Hunnewell rhododendrons may be the oldest cultivated specimens in the United States, as H. H. Hunnewell started planting them in the 1850s and 1860s. Today his Pinetum within the Hunnewell Estates Historic District (Wellesley, Massachusetts) consists of 140-year-old topiary garden of native white pine and arborvite.

READ MORE:

Hayward, Allyson M. “Private Pleasures Derived from Tradition: The Hunnewell Estates Historic District.” Arnoldia 64(4), 2006 [pdf].

Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903)

Olmsted is widely known as the father of landscape architecture, a profession that he was instrumental in defining. He was born in 1822 in Hartford, Connecticut and worked in a number of trades before he turned his hand to landscape design. His career, in the as yet undefined profession of landscape architecture, began with the design for Central Park in New York City. In 1858, he and Calvert Vaux won first prize for their plan for the park which they entitled “Greensward.”

Olmsted’s planning for the Arnold Arboretum began with a preliminary visit to the site in 1874. Work on the design, which included planting plans and road layouts, occurred between 1878 and 1885. Additional work by the Olmsted firm was undertaken between 1890 and 1895 in order to accommodate the acquisition of Peters Hill.

The arrangement and design of the Arboretum’s living collections was collaboration between Frederick Law Olmsted and Charles Sprague Sargent. In their design, both men were in agreement in their scientific and aesthetic goals for an institution that was intended to function both as a pleasure ground for the citizens of Boston and as an encyclopedic tree museum for scientists. Together they created a design based on the formal botanical sequence devised by George Bentham and Joseph Hooker, but which was displayed in a naturalistic fashion. The Arnold Arboretum is the only extant arboretum designed by Olmsted.

READ MORE:

Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site

Library of Congress. Frederick Law Olmsted papers, 1777-1952 [link].

Records of the Original Design of the Arnold Arboretum Living Collections. Archive of the Arnold Arboretum.

Ashton, Peter S. “The Genesis of the Arboretum’s Restoration and Verification.” Arnoldia 49(1), 1989 [pdf].

Roper, Laura Wood. FLO : A Biography of Frederick Law Olmsted. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973 [link].

Rybczynski, Witold. A Clearing in the Distance: Frederick Law Olmsted and America in the Nineteenth Century. New York: Scribner, 1999 [link].

Olderr, Steven and Heuel, Patricia. Toward a Comprehensive Bibliography of the Landscaping and Architectural Work of Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux. Riverside, IL: Riverside Public Library, 1982 [link].

Zaitzevsky, Cynthia. Fairsted: A Cultural Landscape Report for the Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site. Brookline, MA: Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation, National Park Service; Boston: Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University, 1997- [link].

Zaitzevsky, Cynthia. Frederick Law Olmsted and the Boston Park System. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1982 [link].

Jackson Thornton Dawson (1841-1916)

Jackson Dawson was born in England but came to America as a child settling in Andover, Massachusetts. He trained with his uncle who was a nurseryman there and gained early notoriety with his discovery of heather growing wild in Massachusetts. He enlisted in the Union Army during the Civil War and was wounded near Washington, DC. While convalescing he did gardening for people in the area.

After the war, he was engaged as Plant Propagator by Charles Sargent becoming the first employee of the newly formed Arnold Arboretum. Dawson lived and raised his family in the white frame house at 1090 Centre Street. It was here that he also maintained the Arboretum’s propagation facilities, including a greenhouse and outdoor nursery. All of the seeds and cuttings sent by Arboretum collectors in this period, including Ernest Wilson, William Purdom, and John Jack, were raised here. In total he raised 450,718 plants and distributed 47,993 seed packets during his 43 years as Arboretum Propagator.

Dawson was a horticulturist of exceptional ability, and it was said only half in jest, that he could coax life from a dead stick. He was an active member of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society (MHS) and was honored several times by that organization. He was also a noted rosarian and bred several important varieties. He was honored posthumously by the MHS in 1927 by the creation of the Dawson Memorial Medal for “skill in the science and practice of hybridization and propagation of hardy woody plants.”

Arboretum Plant Propagator Jack Alexander is a recipient of the Dawson Medal.

READ MORE:

Connor Geary, Sheila and Hutchinson, B. June. “Mr. Dawson, Plantsman.” Arnoldia 40(2), March/April 1980 [pdf].

Charles Edward Faxon (1846-1918)

“Mr. Faxon joined the staff of the Arnold Arboretum in May, 1882, to take charge of the library and herbarium, which he managed successfully until his death [February 6, 1918] and which he saw grow from insignificance to importance. For these duties he was equipped with a critical knowledge of the New England flora and a facility for acquiring languages which enabled him to read currently those of nearly every country of Europe. It is, however, as a botanical draftsman that Faxon is most distinguished. During his connection with the Arboretum 1,920 of his drawings were published. With few exceptions they illustrate works on trees which have been prepared here. His drawings unite botanical accuracy with graceful composition, and the skill of his pencil has placed him among the few great masters of his art whose names will live as long as plants are studied.”

Charles Sprague Sargent, Annual Report to the President of Harvard, 1917-1918

Originally educated as a civil engineer, Charles Faxon went on to be an instructor in Botany at the Bussey Institution from 1879-1884. In the spring of 1882, Arboretum director Charles Sprague Sargent (1841-1927) asked Faxon to join his staff. Faxon spent the remainder of his career at the Arnold Arboretum as Assistant Director in charge of the library and herbarium until his death in 1918.

Faxon was also an astoundingly talented botanical artist and provided 744 illustrations for Sargent’s Silva of North America.

In his review of The Silva published in Atlantic Monthly in July 1903, John Muir wrote of Faxon’s work,

“At the first glance through the book, everyone must admire the fullness and beauty of the plates. They were made in Paris, from drawings from life, by Faxon, the foremost botanical artist in America . . . these are so tellingly drawn and arranged, [that] any one with the slightest smattering of botany is enabled to identify each tree, even without referring to the text.”

Faxon also prepared many hundreds of drawings for Sargent’s other publications: Manual of the Trees of North America (exclusive of Mexico) (1905), Forest Flora of Japan (1894), for the influential journal Garden and Forest (1888-1898). He provided many of the illustrations for Daniel Cady Eaton’s Ferns of North America (1879-1880). Thirteen of Faxon’s drawings were published in Rhodora, and three in the Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club. Between 1879 and 1913, 1,825 of Faxon’s drawings were published.

READ MORE:

Archives of the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University. Charles Edward Faxon (1846-1918) papers, 1882-1918 [pdf].

“Charles Edward Faxon, delineavit.” Arnoldia 46(3), 1986 [pdf].

Alfred Rehder (1863-1949)

Born in Germany to a family of horticulturists, Alfred Rehder was one of the foremost of plant researchers of his day. After attending Gymnasium, he apprenticed to his father and later continued his botanical studies in Berlin. There he worked as a gardener and in 1895 became the associate editor of Moller’s Deutsches Gartner-Zeitung. He published over a hundred articles during the three years he was associated with the magazine.

In 1898 at age 34, Rehder sailed for the United States to undertake dendrological studies for Moller’s and to investigate fruit growing and viniculture in the United States for the German government. To supplement his stipend from Moller’s, Rehder applied to Charles Sprague Sargent to work on the Arboretum grounds for the princely sum of $1.00 a day. As noted in Arnoldia in 1938, “his first task was to eliminate the weeds in the then newly established shrub collection by the vigorous use of a hoe.” Sargent, impressed by his botanical knowledge and work ethic, convinced Rehder to join the Arboretum staff.

One of his first assignments was to work on the Bradley Bibliography, a massive listing of all the written works on woody plants published before 1900. The research and publication of the bibliography was funded by Abby A. Bradley as a memorial to her father, William Lambert Bradley (1826-1894) an innovator in the field of chemical fertilizers. By the time it was completed, Rehder had compiled more than 100,000 entries.

Ernest Wilson’s plant collections in China stimulated years of work on the part of Arboretum staff members, not the least being Alfred Rehder. Along with identifying and naming new plants, Rehder collaborated with Wilson to write the Plantae Wilsoniae which documented Wilson’s Chinese plant collections. In 1913 he was awarded an honorary Master of Arts degree from Harvard University for his work on the Bradley Bibliography, and in 1918 he became the Curator of the Herbarium at the Arnold Arboretum. Over the course of his career, Rehder authored some 1,400 plant names and published more than 1,000 articles—in both English and German—in botanical and horticultural publications. His botanical legacy is significant—over sixty genera and species bear his name, including many growing in the Arboretum’s living collections like Ostrya rehderiana, a Chinese tree critically endangered in the wild.

Alfred Rehder officially retired in 1940 at age 77, but continued to work on the immense Bibliography of Cultivated Trees and Shrubs Hardy in the Cooler Temperate Regions of the Northern Hemisphere, published in 1949.

READ MORE:

Rehder, Alfred, 1863-1949. The Bradley bibliography : a guide to the literature of the woody plants of the world published before the beginning of the twentieth century. Koenigstein, W. Ger. : Otto Koeltz Science Publishers, 1976.

Rehder, Alfred, 1863-1949. Bibliography of cultivated trees and shrubs, hardy in the cooler temperate regions of the Northern Hemisphere. Jamaica Plain, Mass. : Arnold Arboretum of Harvard Univ., 1949.

Rehder, Alfred, 1863-1949. “Charles Sprague Sargent.” Journal of the Arnold Arboretum. vol. VIII, Lancaster, Pa. : Arnold Arboretum, 1927.

Rehder, Alfred, 1863-1949. “Enumeration of the ligneous plants of northern China … pt. 1-3.” Journal of the Arnold Arboretum. vol. iv, pp. 118-192; vol. v. pp. 137-224. vol. vii. pp. 151-227. vol. xiii pp. 385-409. Part 4, Additions and continuation. Cambridge, Mass., 1923-26.

Rehder, Alfred, 1863-1949. Manual of cultivated trees and shrubs hardy in North America : exclusive of the subtropical and warmer temperate regions. Portland, Or. : Dioscorides Press, 1986.

Wilson, Ernest Henry, 1876-1930 and Rehder, Alfred, 1863-1949. A monograph of azaleas : Rhododendron subgenus Anthodendron. Sakonnet, R.I. : Theophrastus Publishers, 1977.

Rehder, Alfred, 1863-1949. “Synopsis of the genus Lonicera.” Issued October 8, 1903. [St. Louis, Mo.] 1903. From the Fourteenth annual report of the Missouri Botanical Garden.

A complete bibliography of Rehder’s works can be found at the end of Clarence E. Kobuski’s obituary in Journal of the Arnold Arboretum, January 1950.

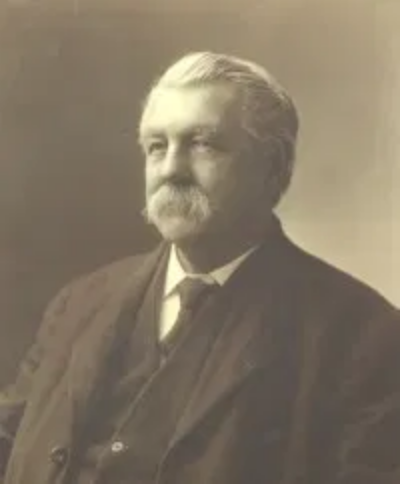

George Russell Shaw (1848-1937)

The son of Samuel Parkman Shaw and Hanna Shaw was born in Parkman, Maine and spent his childhood in Portland. He was educated at Harvard, receiving his A.B. in 1869 and A M. in 1872. While at Harvard he studied architecture and he continued with his studies in London and also at L’Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. While in Paris he married Emily Mott (1848-1927). In 1873, Shaw began a partnership with another young architect, Henry Sargent Hunnewell (1851-1931), son of Horatio Hollis Hunnewell (1810–1902), Arnold Arboretum benefactor for whom the Administration Building is named.

The Shaw & Hunnewell architectural firm was located at 9 Park Street in Boston from 1873 until 1902. The firm designed many Boston residences and local buildings such as Pierce Hall and the Jefferson Physics Building for Harvard College. In Wellesley, Massachusetts the firm designed the Wellesley Town Hall as well as the Library and Houghton Memorial Chapel for Wellesley College. In Boston, their work included the Boston Medical Library and the Ear and Eye Hospital and, in Brookline, Massachusetts the Free Hospital for Women.

In 1919, Shaw’s entry in his 15th Anniversary Harvard College Class Book reads, “my principal occupation has been the study of Pines, with headquarters at the Arnold Arboretum.”

Shaw’s interest in Pinus led to travel to Cuba, Mexico, and Europe to see this genus growing in its native habitat, to collect herbarium specimens, and to study in the libraries and herbaria of botanical intuitions. In Mexico, he traveled with the noted botanist Cyrus Guernsey Pringle (1838-1911) who helped Shaw find and identify the various species of an exceedingly complex group of Mexican pines.

In 1904, Shaw published four articles in The Gardeners’ Chronicle: “The Pines of Cuba”, “Pines of Western Cuba”, “Pinus leiophylla”, and “Pinus Nelsonii.” In his first major publication The Pines of Mexico, (1909) Shaw was able to distinguish 18 species of pines out of a large number that had stymied earlier taxonomists. This publication included a systematic description of each species and variety, a key, notes on distribution, and discussion of previous botanical treatments. In addition to the scientific merit of Shaw’s work he added remarkable illustrations, drawings of cones and needles, and delightful habit sketches of entire trees in their typical surroundings.

Shaw published The Genus Pinus in 1914, which was a systematic, illustrated monograph on pines worldwide. In the ensuing years, Shaw collaborated on Plantae Wilsonianae, Ernest Henry Wilson and Alfred Rehder’s systematic catalogue of the Chinese flora. He also published “Notes on the Genus Pinus” in the Journal of the Arnold Arboretum 5(4), 1924.

In addition to his conifer research, Shaw was a significant contributor to the Arnold Arboretum and made financial contributions to a number of Arboretum projects. He financed the laying of a wood floor and “fire proofing” of the Hunnewell Building attic (renovated in 1993 and occupied by the Arnold Arboretum Living Collections department). Shaw’s conifer collection is now housed at the Harvard University Herbaria in Cambridge as are a collection of his papers, held in the Botany Libraries Archives.

READ MORE:

George Russell Shaw papers. Archives of the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University,

Shaw, George Russell. The pines of Mexico. Publications of the Arnold Arboretum ; no. 1. Boston :, J. R. Ruiter, 1909.

Shaw, George Russell. The genus Pinus. Publications of the Arnold Arboretum ; no. 5. Cambridge : Riverside Press, 1914.